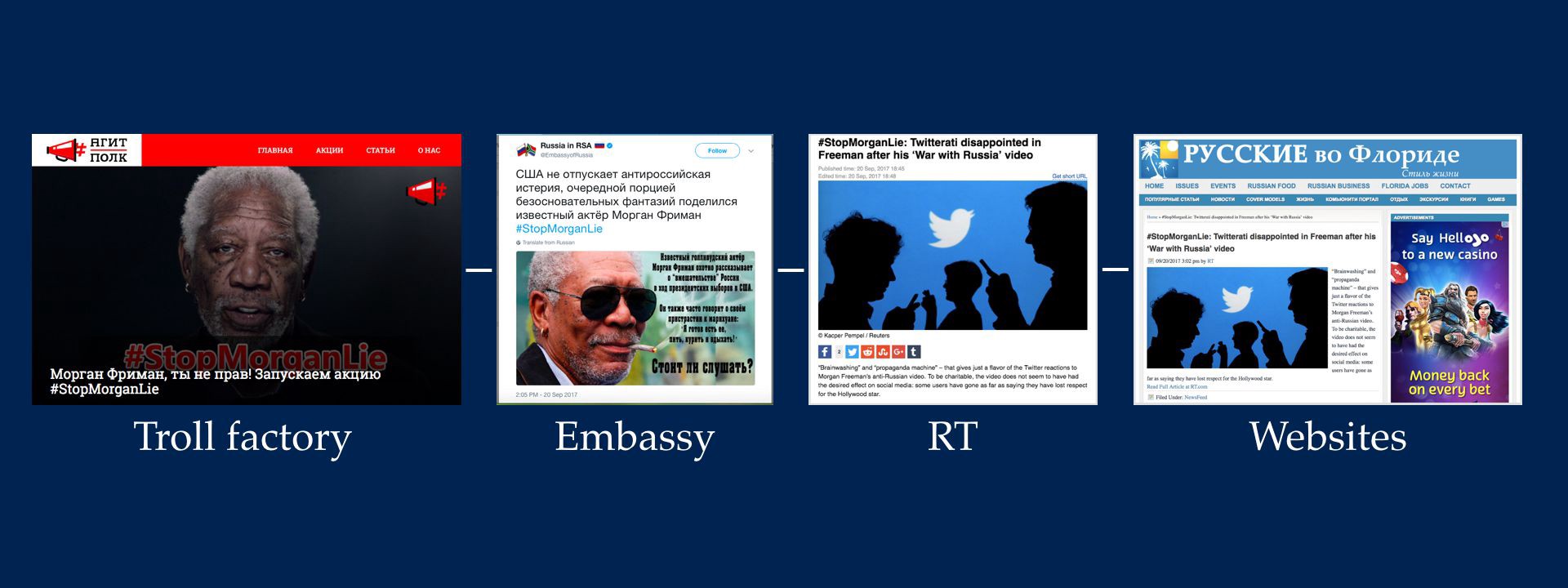

A case study in how Russia’s propaganda machine works

The Russian government’s propaganda and influence operations use a full spectrum model which spans social and traditional media.

Some of the channels it uses are overt and official; others are covert and claim to be independent. They all work together to create the appearance of multiple voices and points of view, masking a coordinated approach.

This post examines one full spectrum case to illustrate the method. @DFRLab examined this case in an earlier post; since then, further evidence emerged, which changed and improved our understanding of the technique.

From the troll factory, with love

The incident in question concerned American actor Morgan Freeman. On September 18, 2017, Freeman fronted a video warning that Russia launched an information war against the United States. The tone was dramatic, but based on facts; the U.S. intelligence community, and many open-source researchers, including @DFRLab, have shown how Russian sources spread propaganda attacking Hillary Clinton throughout the U.S. election of 2016.

https://investigaterussia.org/video/morgan-freeman-warns-russia-waging-war-us

Freeman’s high-profile intervention quickly produced a response in Russia. On September 20, 2017, an online group called “AgitPolk” launched a hashtag called #StopMorganLie, accusing Freeman of “manipulating the facts of modern Russian history and openly slandering our country.”

The Agitpolk website describes itself as “a group of likeminded people united by our shared love for our country,” and insists that it is independent of the government.

The group’s stated purpose is to oppose “anti-Russian hysteria,” a term often used by Russian officials to describe criticism of Russia’s actions, notably its attacks on Ukraine and its interference in Western democratic processes.

Agitpolk focuses its operations on Twitter, calling it “one of the quickest ways of connecting with public actors, politicians and media.” It used two main accounts, the corporate @agitpolk and the personal @ComradZampolit. The latter was effectively anonymous, its profile picture taken from a Soviet film. The word “Zampolit” translates to “Political Commissar”, which is also a reference to Soviet times.

Agitpolk also ran the campaign on Russian network VKontakte (ВКонтакте or VK).

@DFRLab analyzed Agitpolk’s influence and traffic in October 2017. The #StopMorganLie Twitter campaign gathered under 10,000 tweets, including retweets. The VK post was viewed 14,000 times, but liked just 124 times. This is a small-scale impact. On this basis, we concluded that Agitpolk was most likely a voluntary movement.

Subsequently, however, Twitter shared with the U.S. Congress a list of 2,752 accounts which it had traced back to the Russian troll factory in St. Petersburg, and suspended. Both @agitpolk and @ComradZampolit were on the list.

This confirmed that #StopMorganLie was, in fact, a troll factory campaign, and suggested that the agitpolk.ru website was a troll factory creation.

(@DFRLab acknowledges that we misidentified these accounts originally, by concluding that they were not linked to the troll factory. In unclear cases, we prefer to err on the side of caution.)

Watching the spread

Knowing #StopMorganLie began in the https://medium.com/dfrlab/how-a-russian-troll-fooled-america-80452a4806d1, we studied its spread to see how different parts of the Russian propaganda system work together in practice. The first amplifiers on Twitter were apparent bots, posting the hashtag repeatedly without additional comment. Trolls, bots and semi-automated “cyborg” accounts typically work together like shepherds, sheepdogs and electric sheep; see our analysis here.

The hashtag was then amplified by a number of official and verified Russian government accounts, which used their own memes to attack Freeman as a hysterical and ill-informed drug user — a classic example of the strategy of dismissing critics without assessing their evidence.

These posts came quickly. Agitpolk supporters launched the hashtag shortly before 09:00 UTC. The consulate ran its post at 11:49; the embassy followed suit at 13:05 (the timestamp on the screenshot is UTC+1). The consulate also retweeted @ComradZampolit’s call to his “comrades” to join the campaign, as this shot from the machine scan shows:

This certainly indicated that the Russian diplomatic missions not only follow the troll factory’s accounts, but amplify them. At least one piece of evidence suggests that they also coordinate campaigns in advance.

Earlier the same year, Agitpolk ran a hashtag campaign aimed at honoring Russian diplomats, and claimed that it did so “with the support of foreign representations of the Russian Foreign Ministry.” Accounts including the Foreign Ministry, Consulate General in Geneva, and Embassy in South Africa did indeed use the hashtag, confirming the claim.

The missions’ rapid amplification of the attack on Morgan Freeman suggested similar cooperation.

Small, but enough for RT

Despite these high-profile supporters, the Twitter campaign was not particularly effective, especially in English. According to a machine scan @DFRLab conducted at the time, it generated 9,842 tweets, of which just 300 were composed in English (a further 713 retweeted English language posts). These came from 4,003 users, including bots.

Of the English-language originals, many came from primarily Russian-language accounts.

The spread of the troll factory’s hashtag among English-language users was therefore minimal. Even its Russian-language spread was limited.

Nevertheless, the next step in the propaganda chain was for Russian state “information weapon” RT to run a lengthy article (eight paragraphs and 27 embedded tweets) claiming that “Twitterati” were “disappointed” with Freeman’s comments, headlining the hashtag.

The article skillfully avoided stating how little reach the troll factory’s campaign actually achieved in English, using indeterminate terms such as “some users have gone as far as saying they have lost respect for the Hollywood star,” “People said that the ‘democracy’ statement is pure hypocrisy,” and “people on social media said that Freeman’s video is itself ‘shameful’ propaganda.” It also referred to the traffic as an “outcry,” and linked to an article terming Freeman’s comments “anti-Moscow hysteria.”

Tellingly, although the article and accompanying tweet headlined the troll factory’s hashtag, only six of the tweets it quoted mentioned it— all of them from primarily Russian-language accounts. Just two tweets out of the twenty-seven quoted defended Freeman; they were in the final paragraphs.

The article therefore appears to have served two purposes: to amplify attacks on Freeman in general, and to boost the troll factory hashtag in particular.

From RT to the fringe

RT was the hashtag’s main amplifier, spreading the troll factory’s Twitter campaign to new platforms. Its Facebook post of the article was shared a modest 67 times, and drew 662 reactions, not all positive.

A separate share, reproducing Freeman’s video, but adding the caption “Anti-Russia Rant” and the link to the RT article on #StopMorganLie, was viewed over half a million times and shared over 3,700 times.

RT’s article was picked up by a number of disparate sources. They included a Pinterest page focused on socialism and politics; an aggregator site called pressaspect.com; an ostensibly travel-focused site based in Hawaii; and a site dedicated to Russians in Florida.

The RT article did not spread to other mainstream outlets, and, as our scan indicated, the hashtag had limited reach on social platforms. However, it did achieve some further reach on fringe and clickbait sites.

Conclusion

The importance of the #StopMorganLie campaign was in what it showed us about the Russian propaganda machine.

The hashtag was launched by a website which appears to be run from the troll factory. Initially, it was amplified by Twitter and VK accounts, human and automated, run by the same organization.

The campaign was then amplified by the verified accounts of Russian diplomatic missions, which added their own memes to the mix. It was further boosted by RT, which used carefully vague wording and selective tweets to make it look more significant than it really was.

Each of these outlets claims to be a separate institution; in a genuine, pluralist democracy in which the media are editorially independent of the state, they would be. However, their independence is a facade: on this evidence, they work together to promote a common narrative.

The troll factory, RT and Russia’s diplomatic missions are all parts of a full spectrum state communications effort. To understand Russia’s information and influence operations, it is important to understand that approach.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.