#ElectionWatch: Trending Beyond Borders in Mexico

How the “King of Fake News” in Mexico used international Twitter bots and Facebook farms to boost political messages

#ElectionWatch: Trending Beyond Borders in Mexico

How the “King of Fake News” in Mexico used international Twitter bots and Facebook farms to boost political messages

Ahead of Mexico’s presidential election on July 1, a network of Facebook pages and Twitter accounts has been promoting partisan political messages, most of them attacking front-runner Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

The network uses Twitter bots which appear to have been hired from external providers, and Facebook likes from users in India, Brazil and Indonesia. These non-Mexican sources boost the messages by giving them deceptively high numbers of likes and retweets.

The network appears to be connected to Mexican entrepreneur Carlos Merlo, described in local and international media as a “fake news millionaire.” Merlo claims to control millions of automated social media bots, and dozens of “fake news” pages and websites.

Fake accounts and hyper-partisan attacks are troubling at any time, but especially in the immediate pre-election period. In this post, @DFRLab presents our initial findings and methodology. The network is likely far larger than the initial span covered in this survey; more research is needed to verify its full extent.

Meet the Victory Lab

Carlos Merlo is a partner in political consultancy Victory Lab, whose hashtag of choice is #GanaConVictoryLab (“win with Victory Lab”). According to his own comments, reported in a number of interviews since early 2017, the firm offers services including “bot management, containment, cyberattacks, creation of ‘fake news’ sites, crisis management and others.”

Since 2017, Merlo has given at least four major interviews: in April 2017 on Mexican site Univision.com; November 2017, on Mexican site Expansion.mx; February 2018, on Mexican site ADNPolitico.com (the article drew heavily on the November piece); and April 2018, in Spanish newspaper El País.

These interviews painted a broadly consistent picture. Merlo said that he controls a network of over 150 sites, all old enough to appear credible, which mix local news, false stories, and stories planted to benefit political clients, either praising them, or attacking their rivals.

He said that he employs a dozen staff and around 200 volunteers, who create bots, interact with other users, promote content, and celebrate each time one of their false stories makes it into the mainstream news. He also claimed to subcontract some of the work to “sects” of young people who sell social media engagements; Mexico has a number of such sects, with names such as “100tifika” (a pun on the word “científica”, scientific) and “Holk” (Hulk).

Merlo claimed to control a vast network of Twitter bots. In the April 2017 interview, he put the number at 10 million; a year later, speaking with El País, he claimed a more modest four million.

In the Expansion.mx interview, he described the group’s behavior:

“What we do is we use bots to post on social media — on Facebook and on Twitter. We use hashtags so that people can find it, we start to tag (we “at” at) media sites in a very colloquial tone, to media and journalists, and they go with it and publish it. As soon as one of these is big enough, it’s time to push on Facebook, a very strong push in 12 hours, like 90,000 pesos, and it becomes national because it becomes national.”

According to the Expansion.mx interview, his fees range from 49,000 pesos ($2,444 dollars at current prices) for a basic six-month contract, to one million ($50,000) a month for the most expensive.

All interviews agreed that Merlo refused to name the fake sites he runs. @DFRLab investigated his claims, in an attempt to establish a pattern of behavior which would identify parts of his network.

Facebook Amplifiers

The most immediate sources of evidence are the Victory Lab Facebook page and Twitter account. On the Facebook page, an immediate stand-out feature is the “related pages” section, an algorithmically-generated recommendation by the Facebook platform.

The details of the algorithm are not known, but it appears to be based on the behavior and relationships of accounts which like, follow or interact with the page in question. In the case of Victory Lab, the recommendations were all Asian: Indian film director Indrajit Lankesh, Indian Transport Minister Mansukh Mandaviya, and Singapore feng shui master Kevin Foong.

This is the first piece of evidence to suggest that Victory Lab’s main engagement comes from users in Asia, rather than Mexico.

The company’s own posts tend to confirm this impression. All Victory Lab’s recent posts shared links to Merlo’s various interviews, and scored hundreds or thousands of likes. They included this share of an interview Merlo gave to Mundo Ejecutivo TV in February.

This post was suspect because it scored 3,500 likes (the thumbs-up icon), and no other reactions or comment at all. This is wildly unlikely for organic engagement on Facebook following the introduction of multiple reactions in February 2016; a mixture would be typical.

On examination, all the likes came from accounts with apparently Asian names and locations, mostly Indian.

There is no credible explanation for why over three thousand Asian Facebook users would genuinely like a Spanish-language interview with a Mexican fake-news entrepreneur; nor is it likely that a Mexican fake-news company, whose primary market is in Mexico, would run thousands of fake accounts with Asian profiles.

The probability is that Victory Lab bought these likes online from an Asian “like farm,” which uses bots and impecunious users to sell likes.

Other Victory Lab posts showed the same pattern, with thousands of likes, but no other reactions. They included this share of the Expansion.mx interview.

In this case, the likes came from Brazilian accounts, rather than Mexican ones. While it would be plausible for a handful of Brazilians with an interest in Mexican politics to like Merlo’s interview, it is highly unlikely that thousands would, without engaging in any other way.

In this case, it appears likely that the Victory Lab post was boosted by a coordinated, and probably commercialized, group in Brazil which sells likes for money — another “like farm.”

Some of the accounts appeared to be genuine people; others used profile pictures which had been taken elsewhere, suggesting that they were fakes. For example, this post again enjoyed Brazilian amplification.

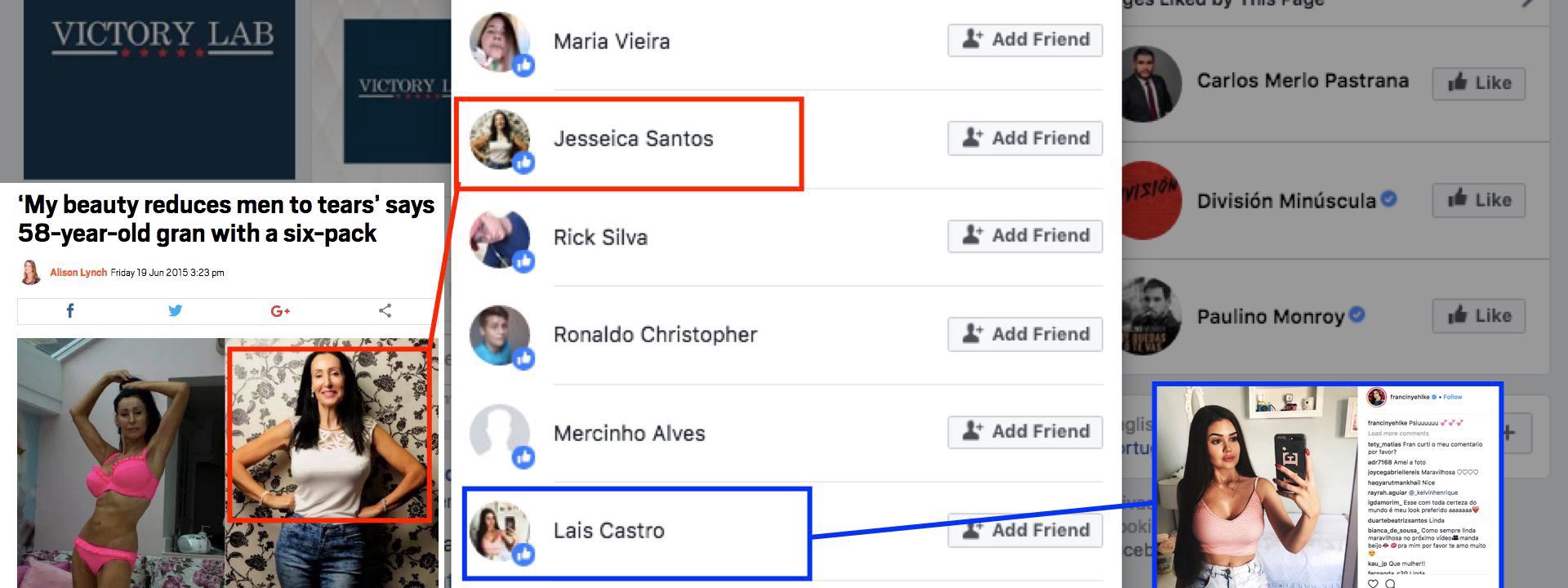

Of the amplifiers, “Jesseica Santos” had a profile picture and background taken from British glamor grandmother Stephanie Arnott…

… while “Lais Castro” shared a profile picture and background with Instagram model Franciny Ehlke.

Overall, Victory Lab’s Facebook posts repeatedly showed the same pattern: high numbers of likes, no other engagements, and an overwhelming balance of users based in India and Brazil, not Mexico.

This repeated pattern strongly suggests that Victory Lab’s main method of promoting its own content on Facebook is to buy likes abroad. This does not necessarily mean that it buys foreign likes for its clients, but it does, at least, raise the possibility.

Twitter Amplifiers

The pattern of amplification on Victory Lab’s Twitter page was similar, albeit from a lower activity base: @Victory_Lab has only posted 69 tweets since it was created in May 2015.

Most of its tweets had a few retweets, or none at all. Two, however, scored hundreds. One was an offer of work to a cab company, @Cabify_Mexico, offering to develop an in-app “panic button” for customers, which received 356 retweets.

Of its 356 retweets, 351 came from accounts which had protected their posts, meaning that their profiles did not show up in the retweets list. Such a high proportion (98.6 percent) is utterly uncharacteristic of organic Twitter traffic, and strongly suggests bot amplification. (@DFRLab saw a similar pattern affecting a tweet by the Atlantic Council which was retweeted by over 100,000 bots: over 30,000 of them were protected.)

To verify the amplification, we scanned the phrase “Hola @Cabify_Mexico nuestros” using the Sysomos online tool. The scan returned 351 mentions in just one minute, a botlike pattern of behavior.

The accounts which retweeted it all had US flags with their profiles, and primarily English-language names, as this screenshot from the scan shows.

As of June 25, all these accounts had been suspended, confirming that this was a botnet, and a clumsily-handled one. Their appearance was not Mexican, but there was insufficient evidence to judge whether they were rented bots, as in the Facebook case, or pseudo-American bots run from Mexico.

A separate post gave a little more evidence. This was posted on November 7, 2016, and reported that Donald Trump had won the US election in Florida.

Once more, 98.5 percent of the amplifiers had hidden their accounts. However, four remained visible, and these did appear botlike. The first was @mrrmidxasxsegr, screen name Валерия Киселева (Valeriya Kiseleva), an account with a very suspicious behavior pattern.

Created in July 2016, this account had posted over 9,000 tweets and 4,000 likes by June 2018, but was not following a single account, and only had twelve followers. It had a Russian bio, but posted retweets in multiple languages, including Arabic, Romanian, French, and English.

Between the retweets, it posted apparently authored posts in English, colloquial English, Portuguese, Korean and French, among other languages.

All of these posts had been made by other accounts before, suggesting that the account was automated to scrape comments from other users, to make its behavior appear more human, and thus escape Twitter’s anti-bot algorithm.

Much the same applied to two of the other visible retweeters, @tamishaandrieu1 and @TameshaKiraly. Both accounts posted retweets in a wide range of languages and alphabets, together with apparently scraped posts from other users.

Like the deleted accounts which retweeted the Victory Lab work proposal, these appear to be bots. However, their posting histories reveal more: they appear to be commercial bots, rented out to the highest bidder to promote whatever content the bidder wants.

It is, of course, possible that Victory Lab itself ran the bots, using them to make money on the side. However, it is at least equally possible that these were simply commercial bots which Victory Lab hired from abroad in order to amplify its messaging.

If so, that would suggest that Merlo’s working practice on Twitter is similar to that on Facebook, hiring in external amplification, rather than creating it.

Twitter Followers

Victory Lab’s Twitter following reinforces the impression of “bots for hire,” rather than the network of at least four million accounts which Merlo claimed to command. Many of its 34,000 followers were faceless, and had apparently Asian names, such as Adi, Sunaryanto, and 이원재.

These accounts appear to have been follower bots. 이원재, for example, was created on December 9, 2017. By June 2018, it had posted just four tweets, but followed over 5,000 other accounts. These covered a wide range of subjects and languages, including Japanese and Korean, and also followed Welsh club rugby.

Verified accounts which it followed included a large number of Turkish users, and the Spanish-language account of industry giant Siemens.

Another faceless follower, @Sunarya92398543, was created the following day. By June, it had tweeted just nine times, but followed 363 accounts, most of them salacious, if not pornographic, and many with Indonesian names. For an Indonesian account to follow Indonesian porn is easily explained; the fact that it also follows Victory Lab renders it unusual.

Other followers of Victory Lab on Twitter appeared to have other nationalities, including Russian and Indian.

The account @vesmava, with a Russian-language profile, also followed accounts in a range of languages, and followed far more accounts than it had posted tweets. On June 26, it was suspended.

Yet another follower was Indian pest-control service @GoldenHiCare, which very largely followed Indian accounts, but somehow slipped Victory Lab into the mix.

Three things are of interest here. First, the focus of these follower accounts lies far away from Mexico; they followed hundreds of Asian accounts, but very few in Latin America. This suggests to us that they are Asian-based accounts for hire, which Victory Lab hired to boost its follower count.

Second, the appearance of Indian and Indonesian accounts — the same geographies which amplified Victory Lab on Facebook — suggests that the Twitter and Facebook boosts may have been acquired from the same organizations, as well as the same countries.

Third, this pattern again suggests that Victory Lab’s practice is to buy in amplification from abroad for its own posts. While this may be a way of hiding Victory Lab’s own purported army of bots, it is an unusual feature, and a highly distinctive one — sufficiently distinctive to merit a search for similar foreign amplification of Mexican election-related traffic.

Same Pattern, Different Pages

An initial search for election-related Facebook content turned up a number of pages, including one called “Contra AMLO,” or “against AMLO” (the usual abbreviation for Lopez Obrador).

On April 23, this page posted a comment on the presidential debate happening at that time. Most of the page’s previous posts only had a handful of likes, but this one garnered 734 likes, no other reactions, and a number of Spanish-language comments from users registered in Brazil.

This resembled the amplification of Victory Lab; so did the amplifiers. They were dominated by non-Mexican names, such as Nilesh Bhardwaj, Muhamad Syawal Rudin, and ﺷﻴﺮ ﺑﭽﻪ ﻫﺎﻱ ﻣﺰاﺭ (an account which gave its location as Mazar-e-Sharif, Afghanistan).

Another post from the same page, dated to May 26, had even more reactions. This time, it gained 131 sad faces, 106 thumbs up and 98 angry faces. All the sad faces came from apparently Brazilian accounts, while the thumbs up came from Asian ones.

There is not enough evidence to conclude for certain that “Contra AMLO” is linked to Victory Lab, but the coincidence is striking enough to demand explanation.

#LordMadrazos

The “Contra AMLO” page shared a number of political hashtags which were also used on other Facebook pages. One such was #LordMadrazos.

A search for this hashtag on Twitter using Sysomos returned a spike in traffic on just one day, May 26 — the same day as the Facebook post. It featured 903 tweets in just over two hours.

Remarkably, all those tweets were generated by just twenty-three users, each of whom posted an average of 39 times.

The most active posters have already been suspended, indicating that they were, most likely, bots. Some of the accounts were still active as of June 25; they included @Rikarda9. Its tweets on #LordMadrazos were deleted before they could be archived (a common behavior pattern among covert Twitter influencers), but the scan collected them.

The account’s profile picture is taken from Argentinian actress Luisana Lopilato. Combined with the high activity on the hashtag, and the deletion of its posts, this marks it as an influence account, not an innocent user.

Actresses were not the only ones to have their photos borrowed for this Twitter spike. Another user, @TonyPadillaDI, was just as active on the #LordMadrazos hashtag before deleting its tweets.

In the below case, the profile picture was borrowed from Israeli singer Judah Gavra.

[facebook url=”https://www.facebook.com/1945884385738863/videos/2042460712747896/” /]

Brazilian and Asian reactions to a post by Hablando de Politica, archived on June 26, 2018. (Source: Facebook / Hablando de Politica)

The pattern is so similar to those of Victory Lab and “Contra AMLO” that it would be easy to conclude that they were linked. However, more research would be needed to prove this point.

#AMLOcuras

#LordMadrazos was not the only political hashtag to feature on these and similar pages. Another was #AMLOcuras, which means “AMLO craziness.”

Checking the traffic on Twitter, this hashtag enjoyed a brief, bot-driven surge on April 23, 2018, the day of the presidential debate.

Once more, the 1,481 tweets it included were generated by a very small number of active users — in this case, 205.

Most of the users were suspended before they could be scanned. One, however, remained: a faceless account called @Edynoesta, screen name “Eduardo Gomez.” This appeared botlike in its behavior; moreover, that same day, it posted a tweet with the Spanish hashtag for “new profile picture,” showing a bearded man copied from a book cover.

These users appear to have taken pains to hide themselves. One of the accounts which tweeted the hashtag was handled @JorgeBaless at the time; its post, captured by Sysomos, ended in the unique post number 988222199097065473.

When the complete URL was entered in a search bar, the Twitter handle changed to @_carolinathh, but kept the same unique post number: https://twitter.com/_carolinathh/status/988222199097065473.

This indicates that the user behind the account changed its handle after April 23, in another attempt to cover its tracks. The GIF below captures the shift of handles in a search bar.

A search for #AMLOcuras on Facebook led to this page, whose first post was made on April 10.

Yet again, most of this account’s posts enjoyed little traffic, but one scored over 3,000 reactions. In this case, they appeared to be Mexican, but included one user with a Chinese screen name, which claimed to be an administrator at “Holk,” the student collective with which Merlo claims to have worked.

[facebook url=”https://www.facebook.com/culturaciudadmx/videos/2165214077081405/” /]

Comments to the post; note the hashtag. Archived on June 26, 2018. (Source: Facebook / culturaciudadmx)

Most posts on this page scored a dozen reactions or fewer, but this one scored hundreds — 767 likes, two laughs and one love. Yet again, the likes came from apparently Indian and other Asian names.

This is the same pattern, yet again, as that encountered in Victory Lab. It is certainly not the sort of pattern one would expect from organic content about Mexican politics, from a page dedicated to Mexican culture. This page is therefore likely to be part of the same network of false amplification.

Conclusion

This article represents an initial snapshot of what is reportedly a much larger influence network. Merlo’s claim was of over 150 fake pages, and up to 10 million bots.

These claims are likely exaggerated: especially on Twitter, the amplification seems to come from commercial bots, bought in from Asia. Nor can it be definitively proven that the accounts and pages listed above are part of the Victory Lab network.

What can be said with confidence is that they all exhibit the same pattern: sudden mass liking by accounts based far away from Mexico, often with a Brazilian or Asian background, and attacks on Lopez Obrador’s campaign. It is likely that further analysis of the hashtags shared by these Facebook pages and Twitter bots will lead to further pages with similar behavior patterns.

With Mexico’s election fast approaching, it will be important to continue analyzing this network, and the infrastructure which supports it.

#ElectionWatch in Latin America is a collaboration between @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.