A reason for skepticism with China’s coronavirus comms

Coronavirus brings into focus the Chinese Communist Party’s history of obfuscating the facts during public health crises

A reason for skepticism with China’s coronavirus comms

Coronavirus brings into focus the Chinese Communist Party’s history of obfuscating the facts during public health crises

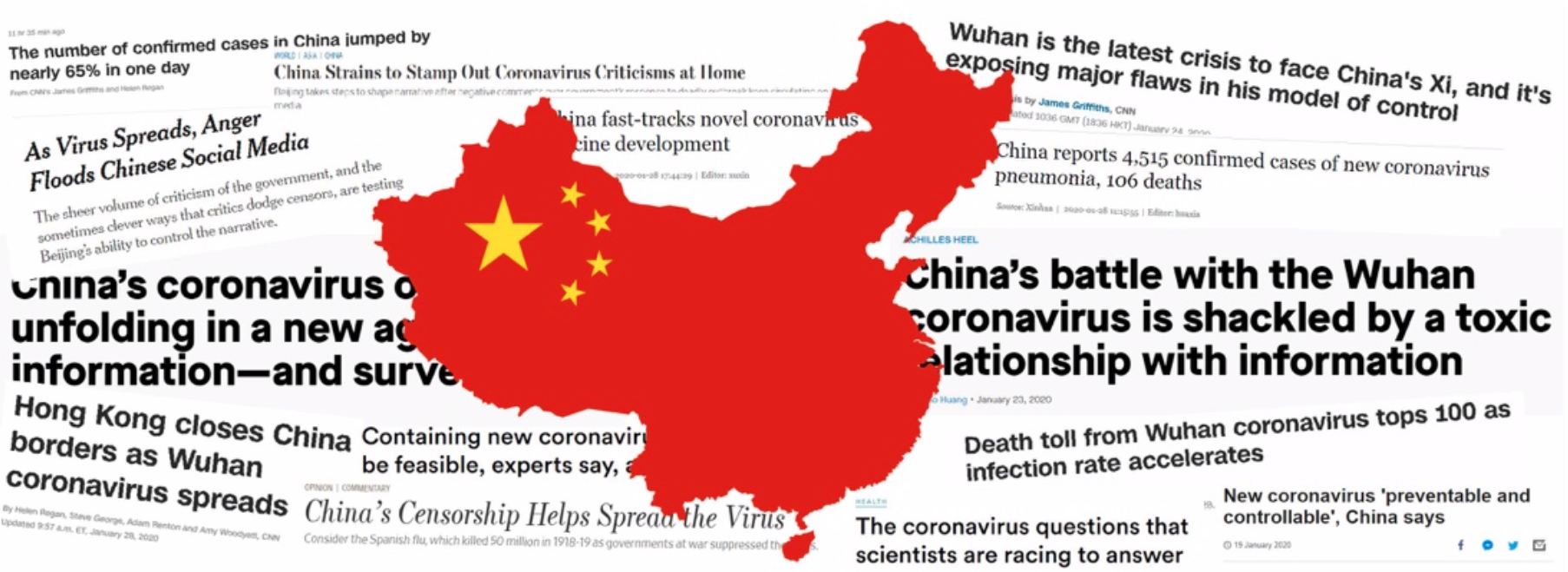

As the novel coronavirus spreads across China and beyond its borders, the country’s government has struggled to maintain control over the flow of information to its citizens, who are increasingly showing their anger over the rapidly escalating situation. While presenting an image abroad of transparency and cooperation, China is simultaneously threatening journalists and detaining people who speak out on social media, the latest in its long history of attempting to maintain tight control over the facts to avoid domestic public scrutiny of a public health crisis.

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasized the effects of false information on global health, branding misinformation — in that case, vaccine-related misinformation — “as contagious and dangerous as the diseases it helps to spread.” In the case of the current coronavirus, the Chinese government’s attempt to control the information flow within the country — the latest act in the CCP’s long pattern of obfuscation of the truth during times of crisis — has allowed health-related mis- and disinformation to flourish, further exacerbating a grave public health threat.

Seeing red, crisis communications

Chinese President Xi Jinping has stated that he is committed to releasing information as soon as it is available in order to “put people’s lives and health first.” Since the outset of the coronavirus outbreak, officially referred to as 2019_nCoV by the World Health Organization, global leaders have been quick to praise the Chinese government and its efforts to stymie the spread of the virus. In the United States, for example, President Trump stated that Chinese officials “have been working very hard to contain the virus” and that the United States “greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency.” U.S. Secretary for Health and Human Services Alex Azar echoed the sentiments of the president, praising the Chinese authorities for their transparency and cooperative efforts.

While these statements may have assured those in the United States that the coronavirus is not an immediate domestic threat, they incorrectly lent credibility to a regime with a legacy of censorship and misreporting on matters pertaining to public health.

As media outlets across the globe continue to cover the spread and governments continue to craft policy responses to this emerging crisis, it is vital to contextualize information stemming from the Chinese government, its associated media outlets, and local social media within the broader information environment in China. Strong domestic controls over media and the digital space call into question China’s reliability as a leader and narrator throughout this pandemic, while also exacerbating the spread of misinformation within China and across global social media networks.

China’s parallel messaging strategy amidst the public health crisis demonstrates its competing objectives regarding the flow of information. On one hand, the country is attempting to compete in the era of a truly international internet, where news moves about relatively unfiltered. The memory of the 2002–2003 SARS epidemic — during which China largely kept the disease under wraps and was severely criticized for its lack of transparency and cooperation with international public health bodies — is particularly omnipresent. On the other hand, the Communist Party of China (CCP) remains preoccupied with what is its primary priority: extinguishing popular discontent before it transforms into unrest, in part by limiting its citizens’ access to information on the CCP’s mismanagement of a national crisis.

SARS, swine flu, and censorship

The primary purpose of China’s extensive censorship activities is to maintain social and political stability, though historically these systems of repressive control have only hindered the government’s ability to respond to public health crises. For example, the CCP faced extensive criticism for its handling of the 2003 SARS outbreak. Despite SARS being classified as highly infectious, the CCP took extensive measures to cover up the virus, at one point hiding SARS patients in Beijing from WHO inspectors. A total of 22 weeks passed before the CCP issued a warning to its own officials “against the covering up of SARS cases and demanded the accurate, timely, and honest reporting of the SARS situation.” International and internal observers concluded that the lack of information on SARS contributed to its international spread; nearly 800 people died from the disease. The head of the Chinese Center for Disease Control publicly apologized for not acting swiftly, and the WHO condemned China for not alerting it soon enough.

While the 2003 SARS case remains a cautionary tale, a more recent indicator is the CCP’s response to African swine flu. China culled at least half of its 440 million pigs over the last year in response to the epidemic. While the CCP ordered the culling and safe disposal of affected animals and made long-term investments in new farms and food hygiene, it failed to coordinate with local authorities who could not incentivize farmers to participate. Despite the massive loss of food and revenue, official data states that only 1.2 million pigs were safely culled. Officially, the location of some 439 million pigs remains a mystery, though food experts believe they were butchered.

Since the SARS epidemic, China has evolved in many ways, including reducing child mortality by half since 2006. But the country, particularly under President Xi, has also clamped down on journalism, imprisoned human rights lawyers, and repeatedly defended its so-called “re-education camps” for Muslim minorities, despite numerous reports of ethnic cleansing and other human rights violations. Overall, Xi’s government has tightened its control over the Chinese public in the years since the SARS outbreak embarrassed the Communist Party.

As a part of this control, the Chinese information environment remains one of the most heavily restricted in the world. The CCP heavily regulates traditional media publishers through direct ownership and oversight via the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP) and State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT), using coercion as a control tactic. State-run Chinese Central TV (CCTV), meanwhile, is the nation’s largest media company.

As internet connectivity has expanded exponentially in the early 2000s, the Chinese government initiated the creation of a sophisticated digital surveillance framework in the form of an isolated, national internet enforced via content filtering firewalls. Moreover, censorship has risen sharply in China following the adoption of a cybersecurity law in 2017 that mandated data localization, real-name registration, and obligated companies to share information with state security agencies. Through a robust legal and security framework, the CCP has full control over the infrastructure and application layers that make up the information landscape in China. The CCP’s strategy of using information control to maintain political and social control is incredibly potent and has made it a pioneer among a new class of digital authoritarians.

Wuhan disinformation arrests

On December 31, 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issued a statement on reported cases of virulent pneumonia linked to a seafood market that was also known to sell birds and other wild game. At the same time, China reported the virus to the WHO as a potential health threat. The Municipal Health Commission’s official statement to the citizens of Wuhan, however, did not read as urgent; instead, the commission took pains to emphasize that viral pneumonia outbreaks are common and recommended general preventative techniques. The Health Commission also stated that of the 27 reported cases, seven were critical.

A day later, South China Morning Post reported that panic had flared up on social media after hospitals were told to report cases of pneumonia with unknown origins. At the same time, China’s official state news agency Xinhua News reported that eight people had been arrested for spreading false information regarding SARS-like viral pneumonia in Wuhan. The report claimed that, in accordance with the law, the public security department investigated the statements and reminded “netizens” that the police would not tolerate the spreading of rumors online.

Poynter journalist Cristina Tardáguila was not able to uncover what happened to the eight arrested citizens beyond social media posts from the editor-in-chief of a state-owned media outlet saying the “misinformers” were not kept in custody or punished. She could not corroborate the posts.

The Chinese government’s punitive response to the spreading of information online raises troubling questions as to why the government was quick to quash internal communication among Wuhan residents while communicating with global organizations, such as the WHO, about the epidemic.

Restricting online platforms

After the Wuhan arrests, Twitter users reported that the spread of information on Weibo, a Chinese social media site, was still being heavily restricted, as citizens of Wuhan asked the government and their fellow “netizens” or any information regarding the spreading pneumonia.

#ChinesePneumonia😂

There is a man asking the information of #Wuhan in #WEIBO (SNS in China), because they cannot get any updates since 3/1, someone did answer him, and 14mins later, the one answered being report, claiming she is spreading fake information.

source:internet pic.twitter.com/XEZQzZ4khc— zozozoie (@zozozoie3) January 5, 2020

As the number of cases increased, scientists and medical specialists requested that the notoriously tight-lipped CCP provide the scientific community with the whole picture to facilitate international assistance. For example, public health officials and members of the public began raising concerns that the outbreak was not limited to individuals who had eaten food at Wuhan’s seafood market. Peter Cordingley, who served as WHO Asia spokesperson during the SARS outbreak, claimed the Chinese government knew the virus was being transmitted via human-to-human contact and was simply hiding that information from both its citizens and the world.

Reactions from Chinese media

Initially, state-run Xinhua News was the primary source of information regarding the spread of the virus, with the station essentially only reporting the information released by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission.

On January 11, after a patient with the virus died, Xinhua reported the death while simultaneously adding that the “epidemic situation is currently controllable.” The same day, the outlet reported that China would share the virus’s genome sequence with the WHO to “safeguard global health security.”

Social media users continued to question why there were no reports of the virus’s spread to other parts of mainland China, as patient numbers increased in Wuhan and Hong Kong reported suspected cases. The virus was referred to as “patriotic” on Chinese social media sites, as it appeared to travel outside of the mainland rather than infecting Chinese citizens in other provinces.

On January 14, journalists from Hong Kong who travelled to Wuhan to report on the spreading virus were detained by police. They were told to delete the footage they had taken of the inside of one of Wuhan’s major hospitals, where the majority of sick patients were being treated. Similarly, TIME reporter Charlie Campbell was threatened with arrest while reporting on the outbreak from the seafood market where the virus is thought to have originated.

Questions have also arisen around the number of recorded sick patients. Both The Washington Post and The Guardian recently ran reports on families claiming their relatives died as a result of the coronavirus, but their cause of death was not recorded as such. South China Morning Post indicated that health officials feared China was underreporting the number of people infected, as confirmed cases jumped from double to triple digits in a matter of days.

Downplaying the epidemic?

President Xi only spoke publicly about the virus weeks after it was reported to the WHO, when hundreds of people were reported sick and the death toll was already rising. The president declared the crisis a “grave situation” and demanded the ruling party remain centralized and united.

On January 26, Wuhan mayor Zhou Xianwang told state broadcaster CCTV that the government’s warnings were not “sufficient” and that bureaucratic processes hindered the timely release of vital information. Zhou acknowledged that, had he known what he does now, he would have done things differently. According to the Financial Times, the virus did not make front-page news in Wuhan’s top-selling newspaper until January 19. Zhou also revealed that five million people left Wuhan before the city was quarantined.

Chinese social media users responded to Zhou’s interview by demanding his resignation.

Disinformation spreads like a virus

Without legitimate and factual information, rumors and disinformation about the virus proliferated online. As news of the virus started to spread, Chinese social media users blamed Hong Kong residents, claiming Hong Kong “thugs” stole SARS samples and spread them in Wuhan.

Interesting fake news by #CCP henchmen.

They framed #HongKong ppl smuggled the #SARS virus samples from lab in university to #Wuhan, trigger the outbreak.

I’ve heard it’s pneumonia?

That’s not the first time Pro-Beijing supporters making fake news, but this one, it’s lame. https://t.co/alM6uZU0IT— Nikki 🇺🇸🌸 (@nikki_miumiu) January 2, 2020

One of the most recent conspiracy theories that gained attention, and was debunked by Buzzfeed, claimed Bill Gates was involved in purposefully spreading the virus. The theory was based on a patent filed in 2015 by the Pirbright Institute, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, for a type of coronavirus that could be used as a vaccine for birds and other animals. Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that include deadly conditions such as SARS as well as mild sinus infections and are found in both birds and mammals. QAnon YouTuber Jordan Sather ignored the reference to birds in the patent’s description and instead suggested Bill Gate’s foundation endorsed the spread of the current novel coronavirus.

Overall impact

While state-run media and President Xi himself have called for transparency and cooperation during this time of crisis, the government appears more inclined to present information to the international community than its own people. The impact, in the case of China’s novel coronavirus, has been serious: thousands of people have been infected with the virus, and, as of January 27, at least 80 people are dead.

The DFRLab will continue to monitor the virality of information about this virus. As coronavirus’ spread remains an immediate and urgent public health threat, it will remain critically important to both understand the spread of dis- and misinformation about the virus, but also the geopolitical implications evidenced by how nations communicate at home and abroad about this issue.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.