Why Bot Makers Dream of Electric Sheep

Using fake social media accounts to attract real users

Why Bot Makers Dream of Electric Sheep

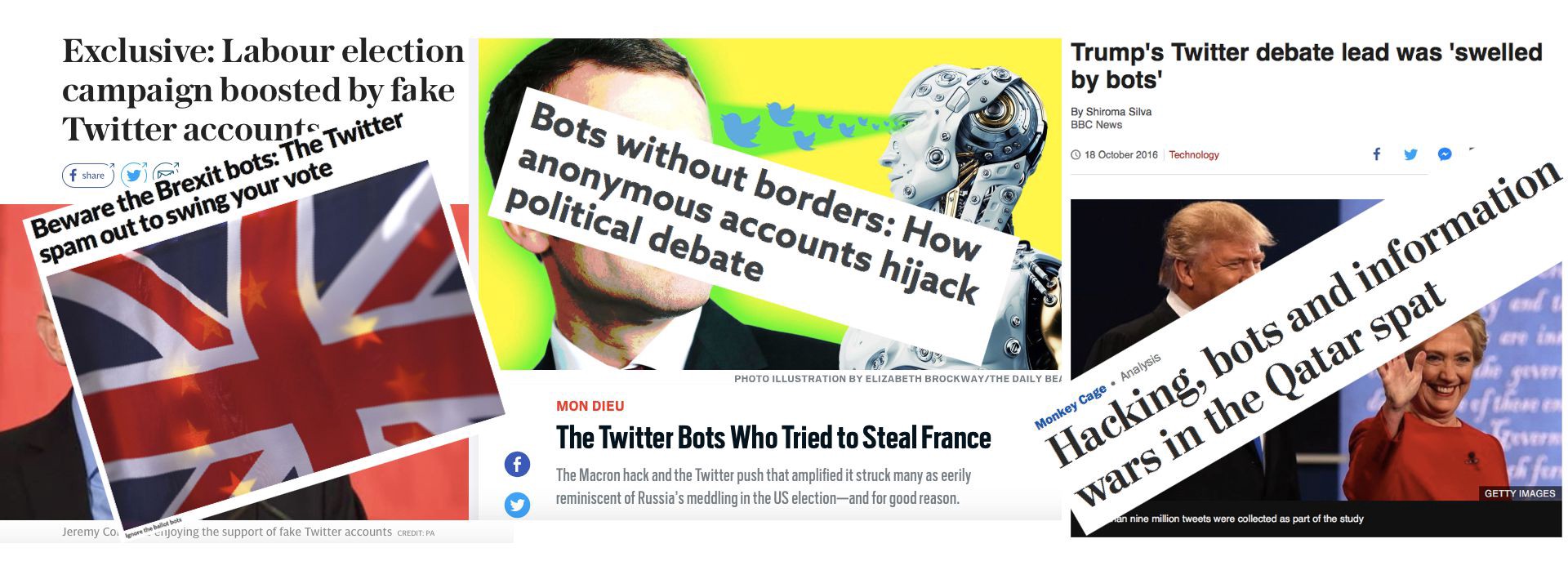

BANNER: A collection of headlines on the use of political bots, from the Daily Beast, Daily Telegraph, The Conversation, Washington Post, New Scientist and BBC.

Social media “bots” have repeatedly made headlines over the past year, accused of driving traffic and distorting debate on social media platforms, especially Twitter, in the US, French, and UK elections. But what are bots, and how do they work?

In social media terms, a bot is an automated account set up to make posts without human intervention. Such bots can play a range of roles, including sharing poetry, spreading news or attempting satire; many accounts make explicit that they are bots.

— TestingBot (@PoetryBot01) January 24, 2017

One sort of bot is created to have a political effect. Political bots typically do not acknowledge that they are automated. Instead, they masquerade as human users, often with a made-up screen name and stolen photo. They artificially amplify political messages, for example by automatically retweeting posts from a set of accounts, liking any tweet which includes certain words, or following a specific set of users.

The effect is to make a user, message, or policy appear more popular and influential than it actually is.

Bots such as these amplify signals; they do not create them. To understand political bots, it is therefore necessary to understand the human users around them.

Shepherds, sheepdogs, and electric sheep

Consider using bots as the electronic equivalent of herding sheep.

Political operations involving bots are typically initiated by a number of “shepherd” accounts, human users with a large following. They are then amplified by “sheepdog” accounts, also run by humans, who boost the signal and harass critics.

The bots (which may be run by the “shepherd” accounts, or sheepdogs, or other actors entirely) act as electronic sheep, mindlessly re-posting content in the digital equivalent of rushing in the same direction and bleating loudly.

This creates the impression of a large-scale social movement. If successful, it can make a policy look more popular than it really is, and attract real users to the chorus.

The shepherds in action

A good example is the Twitter activity around the hashtag #MacronLeaks, launched on May 5, 2017, and targeted against then-candidate, now French President Emmanuel Macron. The hashtag referred to e-mails leaked after Macron’s account was hacked.

The hashtag was launched by a user called Jack Posobiec, a known figure of the US ultra-conservative “alt-right” movement, who has over 100,000 Twitter followers. After Posobiec tweeted about the leaked emails, it was picked up by other far-right accounts, including a French one called @messsmer. These accounts acted as the shepherds, setting the tone of the traffic.

Their posts were retweeted by a network of sheepdog accounts, which combined retweets with aggressive authored posts:

https://twitter.com/sh7401/status/860619147591376899https://twitter.com/jbro_1776/status/860588961324044289

These tweets were then amplified by bots. The most obvious was @DonTreadOnMemes, which posted 294 tweets on #MacronLeaks in three-and-a-half hours; every one consisted of a twitter address and a string of hashtags, in classic bot behavior. (As of June 26, the account had been suspended.)

Other accounts also posted hundreds of tweets in a few hours, almost all retweets. These appear to be “cyborgs,” which automatically repost selected accounts, but occasionally make their own posts, to appear more human.

Taken together, these accounts, and others supporting them, posted over 46,000 tweets in less than four hours, driving the #MacronLeaks conversation into Twitter’s “trending” lists of most popular discussion topics.

This incident was not the first time the French far-right had used social media to shape the conversation surrounding the 2017 presidential election. Throughout the campaign, they managed to make their hashtags trend by carefully shepherding hashtags.

For example, on February 14, @Messsmer launched #LaFranceVoteMarine. Within seconds, a number of other influential shepherd accounts — notably @avec_marine and @antredupatriote — tweeted the same hashtag with different content.

These were amplified by a group of sheepdog accounts, such as @LittleZoma, which posted twenty-seven tweets. This account generally posts a large proportion of its own content, including many replies, indicating that it is unlikely to be automated.

Other accounts, however, were obvious bots, such as @12b5c416f8e5408 (393 posts in an evening, largely consisting of hashtags), @Georges_Resist (379 posts, of which 373 were retweets), and @Patriologue (315 posts, all retweets).

Together, the top ten users posted 3,311 tweets on #LaFranceVoteMarine in one evening, showing how much traffic electric sheep can generate.

Trending, but not a trend

In the case of #LaFranceVoteMarine, the shepherds’ express purpose was to make their hashtag trend, bringing it to the attention of users outside their political bubble.

The bots served as electric sheep, moving in the same direction and bleating loudly, to attract genuine users.

However, it is worth noting the limitations. In the case of #LaFranceVoteMarine, the hashtag failed to draw significant attention from beyond its core supporters, and faded away once the electric sheep stopped bleating.

#MacronLeaks recorded a high degree of traffic — around 25,000 tweets an hour — throughout the following day. However, the hashtag was increasingly challenged by critics, who disrupted the chorus, rather than joining it.

Thus, the combination of shepherd accounts, sheepdogs, and electric sheep cannot guarantee that the information spread takes root and redefines the conversation at hand. It can, however, push a message into the trending lists, giving it the best chance of attracting new users.

This post was originally published on the Atlantic Council’s New Atlanticist blog in the framework of #DisinfoWeek.