Four Questions For Twitter, Facebook, Google, and Everyone Else

Hearings for how can we cure social media without killing them

Four Questions For Twitter, Facebook, Google, and Everyone Else

Hearings for how can we cure social media without killing them

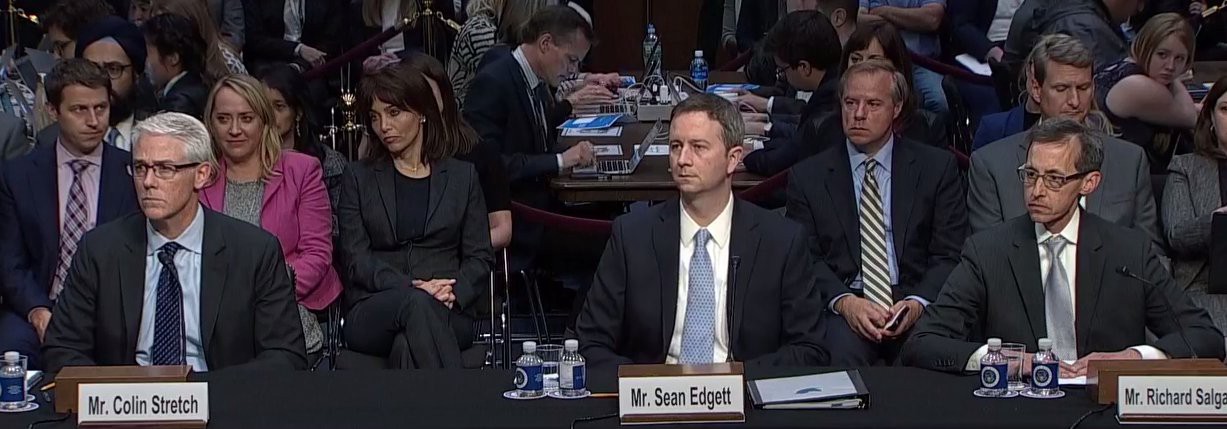

On October 31, Twitter, Facebook, and Google finished the first of two days of public hearings on Capitol Hill on social media’s influence on the 2016 U.S. presidential election. After a hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism, the social media giants testify to the Select Committee on Intelligence of both the Senate and House on November 1. Despite a vague title, the hearings will be laser focused on tools used by Russia to influence the outcome of America’s democratic process.

As legislators, social media companies, and journalists gather on Capitol Hill, each group in the room must do more to harness opportunity and mitigate vulnerability in a rapidly evolving information environment. Each group’s actions are co-dependent, so the solution starts with a common understanding of the issue at hand.

The questions are likely to be angry; the answers are likely to be unsatisfactory, because they will have to explain not just systemic failures, but apparent indifference. But the most important question may not be asked at all. Senators are certain to demand, “What are you doing about it?”, and the answer will make interesting soundbites; but the question they need to ask is, “What do we need to do about it?” What are the questions which our societies need to answer, so that we can defeat the dangers posed by social platforms, without destroying the platforms themselves?

If we want to defeat the disinformation which has metastasized on social media platforms, we have to think of individuals first. Each person must be more digitally resilient.

Government, social media companies, and media must take collective action with a focus on constituents or consumers. Here are four questions for the hearing to build a common denominator for action.

What is your platform designed to do?

Facebook and Twitter are not just media: they are social. The very nature of social media is to connect rather than inform us. However, a majority of U.S. citizens now consume news on social media. During 2016, 62 percent of Americans got news on social media. Companies now have a responsibility to both connect and inform simultaneously.

Facebook seems not to know how to solve its problems. Congress seems not to know how Facebook works. https://t.co/1ChG4pYstl

— nxthompson (@nxthompson) November 1, 2017

In the online information swirl, Russian covert operatives abused social platforms to spread deceptive and divisive messages with impunity for years. Theirs was not a one-size-fits-all approach. Each platform is different. In fact, entire industries exist to engage an audience effectively by tweaking content just right for maximum reach on each separate platform.

This detail is easy to overlook in scoping the solution to a problem as murky and pervasive as Russian disinformation operations, but it is vital. Any response to the disinformation threat will need to take into account each platform’s purpose, and the way people use it, to avoid killing the platform with unintended consequences.

What is the limit of anonymity on social media?

Anonymity is the internet troll’s armor. A Russian operative sitting in an office in St. Petersburg successfully posed as the unofficial account of the Tennessee Republican Party more than eighteen months, lost in the swirl of online commentators with names that read like the cast list of Game of Thrones.

10K bot followers I didn't ask/pay for this afternoon. They didn't get my Giga Pet joke. More #BotSpot from @DFRLab: https://t.co/9UwMQnRau9 https://t.co/rXnYEzBii8

— Graham Brookie (@GrahamBrookie) August 29, 2017

Managing this vulnerability is far harder than just demanding the companies publicize any data they have left on the Russian operations they hosted.

For years, bot herders have been running tens of thousands of hijacked accounts with stolen avatar pictures and made-up names, or no avatar pictures and names which are a jumble of letters and numbers, using them to promote everything from commercials to Communism (bots have no sense of irony, as in the case at left).

Nameless, faceless trolls like these spewed messages of hate across America throughout the election; bots acted like an online megaphone, shouting down real internet users with torrents of abuse. (For one example of how this works, read here.)

But anonymity is not just armor for trolls: it is armor for everybody. In repressive countries, the rule for dissidents can literally be “publish anonymously or perish”; even in the democratic world, the steady flow of headlines like “Internet trolls ruined my life” is a reminder of why invisibility is bliss. Being exposed can be dangerous.

How would our societies react, if the social platforms which enable us to chat, argue and socialize from our lonely keyboards, insisted that every user publish their real identity? @DFRLab investigated fringe groups moving to alternative, more lenient, social media options when companies like Twitter and Facebook cracked down on them for terms of service violations. Whatever the moral arguments, the practical result for the platform would be shipwreck.

Questions must be asked about the degree of anonymity which platforms allow.

- Should it be harder to create a fake account? Absolutely.

- Should platforms encourage users to have their accounts verified? Definitely.

- Should platforms outlaw the practice of using someone else’s name or photo? We enjoy some parody accounts.

- Should platforms store their users’ personal data and hand them over to the security services whenever they make an unacceptable post? See you on the barricades.

And what about the rest of us? Social media companies house and manage the market for anonymous accounts, but they did not make the market. There is a market for fake accounts. Newspapers and TV shows embed posts from anonymous accounts to color their stories. The Washington Post did it, and quoted a Russian disinformation account; online platform ivn.us did it, and quoted a fake Julian Assange account. There are rules for using anonymous humans in journalism; which don’t seem to universally applied to unverified accounts.

Politicians and activists also promote or retweet anonymous accounts, as Donald Trump Jr. and Kellyanne Conway did, only to discover that they were fakes. A retweet is not (necessarily) an endorsement, but it can be an embarrassment.

What about each one of us, every time we share a post because it’s emotive or interesting without checking who posted it?

We cannot, and should not, do away with anonymity online, but we need to find a way of cracking the trolls’ armor. So the questions that politicians, legislators, journalists, and everyday consumers have to answer are: where should my anonymity stop and why should I believe yours?

Do you have a right to be forgotten?

One of the questions which is sure to be asked by legislators is: why did you delete the data from the Russian troll factory accounts, once they had been identified?

The answer will be: for privacy.

For investigators, the answer is maddening. Those accounts were run from the troll factory in St. Petersburg; without knowing what the accounts posted and who amplified them, the investigators are starting a search for the rest of the network with two strikes against them.

We can still find traces, in the mentions and replies from other users; we can reconstruct some of their activity, as this example shows. But these are puddles, splashed across the desiccated sand of forensic research. The fountain has dried up.

Social media analyst Jonathan Albright exposed the likely reach of Russian ads on Facebook, only to see the data he found erased. He explained:

This is public interest data. This data allowed us to at least reconstruct some of the pieces of the puzzle.

But as Facebook retorted to the Washington Post at the time:

We identified and fixed a bug in CrowdTangle that allowed users to see cached information from inactive Facebook Pages. Across all our platforms we have privacy commitments to make inactive content that is no longer available, inaccessible.

“We have privacy commitments.”-Facebook

They do indeed. It is one of the things that distinguish the social media from traditional media. And the question of where the right to privacy bounces back off the right to uncover malicious fakes is as thorny as the question of anonymity.

This is a question of principle, and of law. In Europe, the “right to be forgotten” was established by the European Court in at least some circumstances. Twitter, Facebook, and Google published privacy policies, which include the right to have data deleted once the account which created them is deleted.

For media, these privacy policies would be unthinkable; for social media, they are essential. Would you sign up to Facebook or Twitter if you knew that they were going to keep your embarrassing selfie forever?

https://media.giphy.com/media/EkDhogNB3yo3C/giphy.gifhttps://media.giphy.com/media/F95WSkkosQ9YQ/giphy.gif

What goes for normal users also goes for trolls. If you, and I, have the right to be forgotten, so does the troll in St. Petersburg, the bot herder in Utah, and the network of a thousand scantily clad females who all have the same avatar picture.

This is the crunch debate. Even more than anonymity, privacy is the cornerstone of the social media. One reason that users are comfortable sharing every aspect of their lives is that they feel they can control access to the information. Users make personal information public, but feel it is private.

That is a mostly ungoverned paradox of social media platforms: they are simultaneously private and public, closed and unlimited. In the gray space between private and public, abusers of the internet thrive.

Facebook, Twitter, and Google may want to, but they cannot solve the privacy problem alone.

Attacks and attractiveness

The third question is, in many ways, the most important. Anonymity can be lifted, privacy can be limited, but users will be scared away when it happens. The existential question for each company, which investigators and legislators must take into account, is:

How do you solve the problem without killing the company?

Some steps appear easier than others. The social media companies could, and should, be much more aggressive against trolls and botnets which amplify abuse. This might actually increase their user base, as the idea of social platforms as a family-friendly community place takes hold.

They should also explore ways to make automated posts more obvious. There is nothing wrong with automation itself; the problem comes when accounts, or networks of accounts, are automated or deployed by nefarious actors to post hundreds of disinformation messages a day, and subsequently when real users fall for them. Downgrading or marking automated posts would increase understanding of bots and reduce their influence.

Again, taking action on automation, especially on Twitter, might well increase the platform’s credibility.

Anonymity and privacy are key. As long as anonymous accounts are allowed to flourish, trolls and agents will flourish among them. As long as posts can be deleted without recall, researchers and the public will struggle to expose the disinformation network understand the scope of the damage caused.

However, the risk of unintended consequences remains by high. Without the armor of anonymity and the assurance of forgetfulness, how many normal users will be willing to share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences online?

Can the committee commit to collective action?

In many ways, the threat of Russia’s influence operations via social media are a forcing function for unaddressed governance challenges growing like weeds in a rapidly evolving information environment.

This is the essential debate. Facebook and Twitter are not just media, they are social media. They survive because everyday users trust them for anonymity and privacy; they can be expected to fight in order to keep that trust.

Government for and by the people relies on trust, too: trust in information, trust in institutions, trust in politicians, and trust in the media. Trust in democracy is built on objective information. Malevolent actors used social media to undermine our trust.

This debate is not just about Twitter, Facebook, and Google. It is about freedoms — and where the inherent tension individual’s freedom stops and society’s freedom starts. The solution cannot only involve actions by social media companies but requires collective action by all of us.

Watch the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence open hearing “Social Media Influence in the 2016 U.S. Elections” at 9:30am EDT:

Watch the House Permanent Select Commitee on Intelligence “Russia Investigative Task Force Open Hearing with Social Media Companies” on November 1, 2017 at 2:00pm EDT:

Re-watch the Senate Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism open hearing “Extremist Content and Russian Disinformation Online: Working with Tech to Find Solutions” from October 31, 2017 at 2:00pm EDT:

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.