Last Hospital in Aleppo

What open sources tell us about strikes on hospitals during the siege

Last Hospital in Aleppo

Share this story

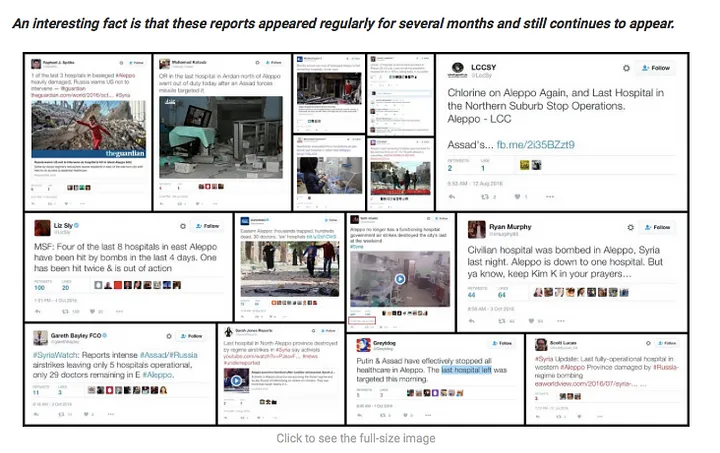

The “Last Hospital in Aleppo” was one of the recurrent stories of 2016. Throughout the second half of the year, reporters across the world wrote stories about the “last hospital in Aleppo” being attacked, or ceasing to operate.

Often, days after such articles were published, reports would emerge of another attack on another hospital — leading to online questions about how many “last hospitals” Aleppo possessed.

There's only so many times ppl can be interested in Aleppo's last Hospital being bombed by Russia

It's been destroyed 100x pic.twitter.com/IYqFHdBd1f— ⭐⭐TrumpNation🇺🇸 (@roz__ke) December 18, 2016

What do open sources tell us about the hospitals of Aleppo, the air strikes which destroyed them, and the accounts which challenged the reporting, now that the siege has ended?

A trail of destruction

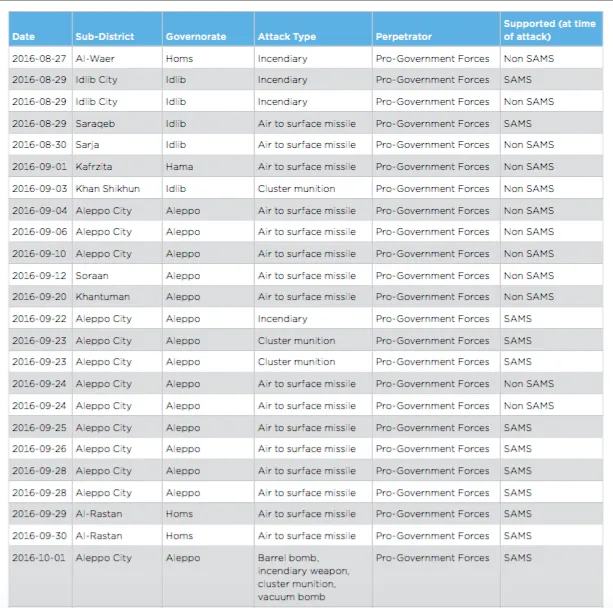

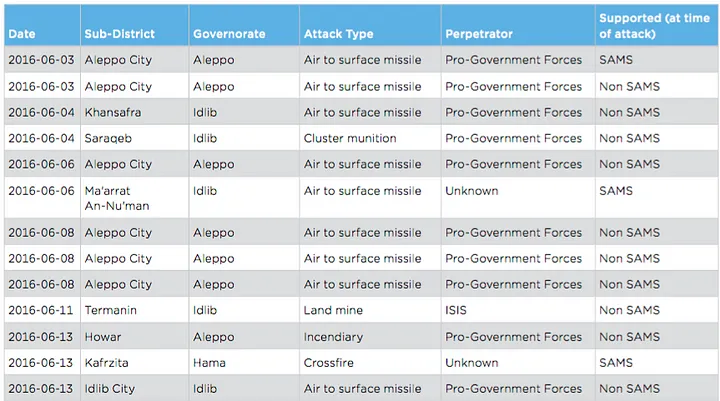

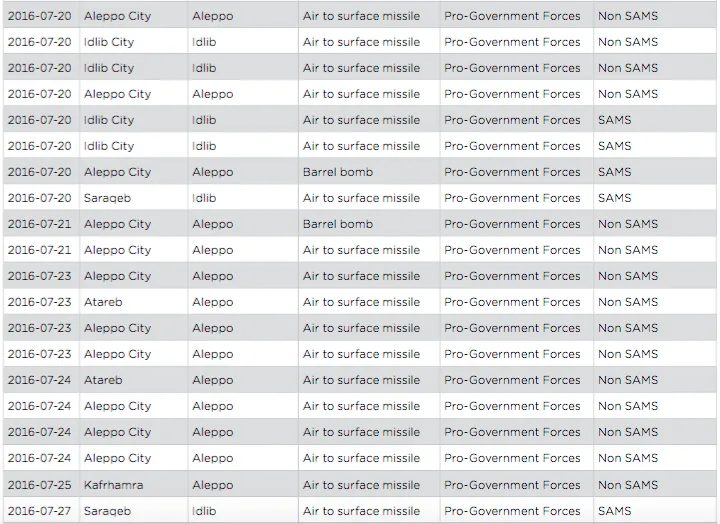

According to a new report by the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), released on January 11, there were 172 verified attacks on hospitals or medical facilities recorded across Syria between June and December 2016. Of those, 73 verified attacks — 42 percent of the total — were recorded in the besieged, rebel-held half of Aleppo.

According to the SAMS report, the strikes used a wide range of weapons, including air-to-surface missiles, cluster munitions, barrel bombs and incendiaries. The strikes are listed by date, district, governorate and perpetrator.

The listing includes all verified attacks, including those attributed to non-government forces:

This data set, the most comprehensive we have to date for incidents in 2016, can be cross-referenced with other open source information such as security camera footage and social media posts to understand what was happening with Aleppo’s hospitals, and how the “last hospital in Aleppo” story came round so many times.

According to UN operational plans, in mid-August there were 9 “hospitals” and 15 clinics in east Aleppo. Of these, ten had no doctors, or were closed. Of nine SAMS-supported hospitals and clinics in Aleppo city, only three offered trauma or intensive-care facilities — the hospitals known as M1, M2 and M10. Only one of these clinics, M2, also had a pediatric faciltity, to treat children.

Some of the clinics were “staffed only by nurses (providing first aid) or midwives”. The varied nature of the clinics and hospitals, and the fact many did not offer first-responder trauma treatment and emergency services needed in an active warzone with frequent bombing, meant there were, in essence, fewer useful hospitals than the bare numbers suggest.

Attacks on hospitals have been well documented across Syria throughout the conflict. Physicians for Human Rights reported that there were at least 400 attacks on medical facilities in Syria from the beginning of the war through 2016, mapping them by region:

July 2016

As one example, a number of Twitter accounts began posting on the “last hospital in Aleppo” being bombed in late July:

Last hospital bombed in Aleppo. Russian and assad strikes destroyed them all https://t.co/lB3cpRzIY9

— Robert van der Noordaa (@g900ap) July 27, 2016

During the week leading up to this influx of tweets, SAMS lists 11 strikes on hospitals in Aleppo city, all using air-to-surface missiles:

According to a statement by Human Rights Watch published on August 11, four hospitals and the blood bank in Aleppo were hit in this period, and all were forced to “temporarily shut down”. The report quoted the World Health Organization as saying that there was only one hospital in eastern Aleppo still offering obstetric and gynaecological services.

A separate tweet narrowed down the claim to saying that the last functioning children’s hospital had been struck twice in twelve hours.

Unicef: 4 hospitals & blood bank bombed in Aleppo 23-24 July. Last remaining paediatric hospital hit 2x in 12hrs, killing baby in incubator.

— Louisa Loveluck (@leloveluck) July 27, 2016

Under the circumstances, to refer to the M2 hospital as the last children’s hospital in east Aleppo was entirely correct. However, a number of hostile tweets challenged the reporting as “anti-Russian propaganda”, focusing on the apparent paradox of a “last” hospital being struck more than once.

Anti-Russian propaganda in action: "Last hospital in Aleppo destroyed" for umpteenth time https://t.co/PgTD3yaErI

— Organic Universe (@ShelterSense) August 3, 2016

However, there is nothing paradoxical about these reports. They indicate that some hospitals in eastern Aleppo had stopped working by July 2016; that a series of air strikes damaged a number of the remaining ones around 23 July; and that the hospitals were temporarily forced to stop working.

October 2016

Another round of reporting on the “last hospital” story came in October. Between September 22 and October 14, SAMS lists 13 strikes on hospitals in Aleppo City. These included two of Aleppo’s largest surviving hospitals offering ICU and trauma facilities, the M10 or al-Sakhour hospital and the M2 hospital, both struck multiple times.

Using open source materials, the Bellingcat group of investigative journalists was able to show the progression of attacks on the M10 hospital, despite Russian government claims that no such strikes had been carried out:

Again, the reports led to online attacks which called the credibility of media reporting into question because of the use of the word “last”:

One thought that last hospital in Eastern Aleppo has been destroyed last week as presented in western media… https://t.co/3x7ZuP0MbV

— peter pobjecky – #FreeAssange (@peterpobjecky) October 13, 2016

This wave of tweets appeared to have a degree of coordination, with multiple users sharing the same memes. Significantly, pro-Kremlin disinformation site SouthFront had by this time prepared an article attacking the claims as “war propaganda”, together with a collage of photos that was shared by a number of pro-Kremlin accounts.

In line with its usual style, SouthFront pulled no rhetorical punches:

“We have only two variants: either hospitals in Aleppo ‘are growing like mushrooms after rain,’ and every week Russian fighter jets bomb a newly-made hospital in the city, killing dozens of injured people, or all such reports are just another example of the war propaganda, aimed to set a foothold for unlawfull [sic] actions of the US-led anti-Assad coalition against the Syrian government.”

However, the repetitive nature of the reporting is once more explained by the repetitive nature of the strikes themselves. The M10 hospital alone was hit on September 28, October 1, October 3 and October 14.

The involvement of South Front in the online attacks gives them the appearance of a pro-Kremlin campaign designed to distract attention from the regularity with which Aleppo’s hospitals were being repeatedly hit.

November 16–18

Between November 16 and November 18, SAMS lists seven more attacks on medical facilities in eastern Aleppo, including missiles, barrel bombs and artillery.

It was after these attacks that most news reporting on the ‘last hospital’ came out. This was because repeated attacks on the same hospitals had impaired their capacity to operate, in particular to offer open services to those needing emergency care, as so many in east Aleppo did at the time.

According to SAMS:

“Shortly after the destruction of the SAMS-supported M10 Hospital on October 3 in a 10-day span where the facility was targeted four times, the attacks on medical facilities intensified to the point where the Aleppo Health Directorate announced the suspension of all medical services in all of besieged Aleppo. Between September 20 and the Health Directorate’s announcement on November 18 — a span of 60 days, we had documented 23 attacks on medical facilities or personnel in Aleppo. All hospitals in Aleppo had been either destroyed or severely damaged.”

These reports led to a new round of mockery, with the same themes and memes recycled and attributed to different authors:

https://twitter.com/domihol/status/799290508464058368https://twitter.com/Navsteva/status/798909905449140224

These online attacks all made the same basic argument: media had reported strikes on the “last hospital” many times. The hospitals had kept on functioning. Therefore the media reports were fake, and the story of hospital strikes was a case of anti-Syrian and anti-Russian propaganda. The argument ignores the simplest explanation: that the hospitals had kept on working despite being hit.

However, the focus on the phrase “last hospital” serves to distract attention from the word “hospital”. By starting a debate on whether a given medical facility was the last one of its kind or not, it sidesteps the debate on why the facility was struck in the first place.

Thus, the story of the “last hospital in Aleppo” gives us an insight into the legitimate operational reasons behind the reporting of the ‘last hospital in Aleppo’, the conduct of the bombing campaign — and the distraction campaign which sought to defend it.