Nearly three years after the Russian seizure of Crimea, we have a vast amount of open source digital evidence surrounding the ongoing conflict that resulted from this forceful annexation and the flight & subsequent ousting of ex-president Yanukovych.

In particular, hundreds of publicly available satellite images reveal changes in the Donbas landscape, especially in the growth and destruction of military positions. In a series of posts, we will attempt to provide a history — though by no means a definitive one — of major developments in this conflict, the conditions from which the Minsk II agreement came to be, and how the terms of this agreement have, and have not, been implemented.

This is the first of a multi-part series from DFRLab examining the conflict, with this entry leading up to the first Minsk agreement on September 5, 2014. There are many major events from the war that are only alluded to or not included, but the included materials represent the general trajectory of the conflict.

Crimean takeover

Though little blood was shed in the Russian takeover of Ukrainian military bases in Crimea, many of the same men who led “self-defense” groups seizing Ukrainian assets in Crimea later fought in eastern Ukraine. The most famous example of these men is Igor “Strelkov” Girkin, who admitted to leading “negotiations” in Simferopol during the seizure of the Simferopol Airport. He was also filmed at a confrontation between a “self-defense” group and Ukrainian police. Girkin later became a key military commander in Sloviansk and Donetsk before returning to Russia.

The military base in Perevalne, Crimea has seen tremendous change since a group of “self-defense” forces (many of whom were enlisted Russian servicemen) surrounded and seized the area. Ukraine’s 36th Coastal Defense unit was stationed in the base, but after the Ukrainian forces either surrendered or changed sides, Russian forces moved in, including the 126th Separate Coastal Defense Brigade. In the animation below, we can observe the change at a vehicle yard in the northeast corner of the base from Ukrainian control to Russian, after it was seized in March 2014.

There was a signficant uptick in the number of vehicles in the area, including an expansion to the right (north) of the previous confines of the vehicle yard. New imagery from Digital Globe/NextView on August 26, 2016 shows that this expanded area is no longer used as a vehicle yard.

Additionally, comparing the northern area of the base from March 2014 to September 2016, there is new, visible construction. This construction aligns with a Reuters report from November 2016, in which journalists studied public tenders for new construction at the base. The report describes that the construction at Perevalne will “include dormitories for more than 1,000 soldiers, residential buildings with more than 300 apartments, an ammunition depot, hangars for more than 500 military vehicles, an artillery range and dining facilities. A new school and a kindergarten with a pool, as well as barracks for a military orchestra, are also planned, the documents show.”

Seizure of key buildings in the Donbas

In April, unrest shifted to eastern Ukraine, where “self-defense” forces, supposedly consisting entirely of locals but also including Russian and former Berkut forces, seized key government and military buildings throughout the Donbas. To this day, some of these seized buildings are controlled by separatist/Russian forces, including in Donetsk and Luhansk. However, in some cities, Ukraine succeeded in offensives to retake seized territory.

Sloviansk

One of the locations subject to a Ukrainian siege was Sloviansk. The police station in Sloviansk was seized on April 12, 2014 by the same “local” who assisted in the takeover in Simferopol — Igor “Strelkov” Girkin. A video from the day of the takeover from Ruptly shows how the station was seized, with a Russian flag hoisted.

Satellite imagery from April 18, 2014 shows a blockade south of the police station:

Ukraine eventually recaptured Sloviansk after a costly siege and multiple offensives, and Igor “Strelkov” Girkin fled the city on July 5 for Donetsk.

Mariupol

Ostensibly local pro-Russian forces also seized key buildings in Mariupol, the second-largest city in the Donetsk Oblast. The city council building was seized by pro-Russian gunmen/demonstrators in April 2014, and was recaptured by the Ukrainian army on May 8. In the satellite image below, barricades and debris set in front of and behind the building are visible during the time of Russian/separatist control:

On May 9, 2014, the police headquarters in Mariupol was the center of one of the conflict’s bloodiest days before the summer escalation, in which dozens of people were killed after clashes broke out between Ukrainian forces and armed separatists & local police officials. The exact details of this clash will likely always be shrouded in controversy and uncertainty. Below, we can see the destruction to the Mariupol police headquarters after a fire was set during the May 9 clashes.

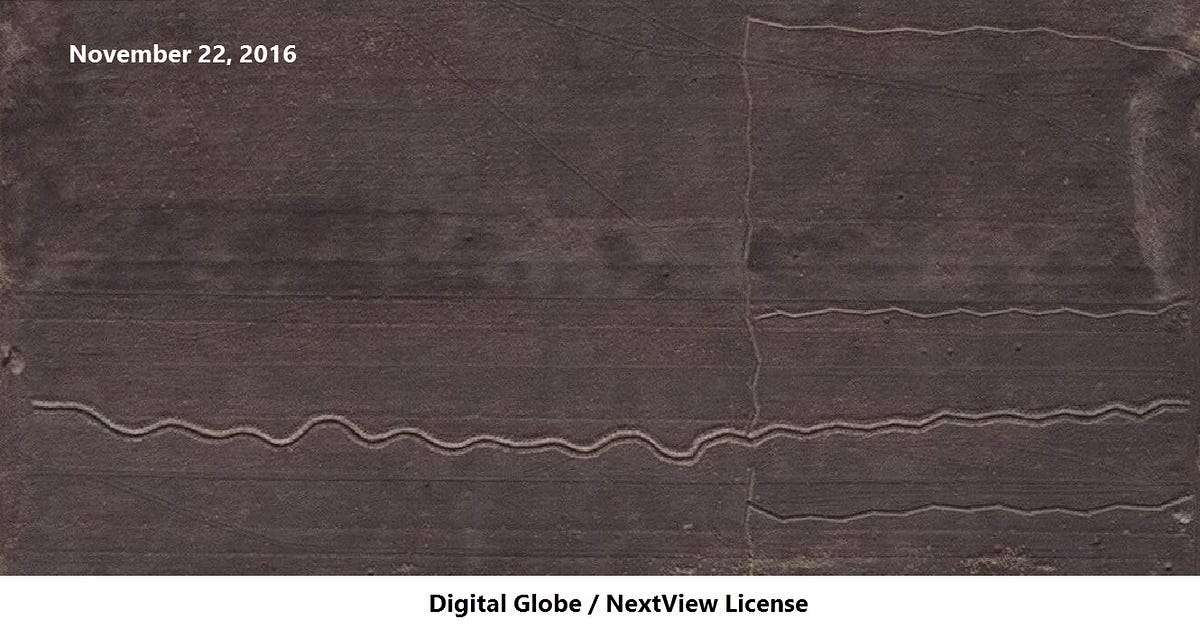

In June 2014, Ukrainian forces recaptured Mariupol, where they are still in control and have made the city the home of the Regional State Administration. Until August 2014, the city was mostly peaceful, but escalations from Russian forces turned the area into a conflict zone again, including from artillery strikes conducted from Russian territory. Since then, the bulk of the fighting near Mariupol has been in the small towns 10–20km to its east, including Shyrokyne. The landscape near Shyrokyne has been transformed due to the war, with farmland becoming the site for newly dug trenches.

The trenches between Mariupol and Shyrokyne have been expanded in the past two years, now creating a canal-like pattern through the fields west of Shyrokyne.

Ukraine’s recapture of Mariupol did not end the southern front of the conflict, but it moved the front lines back about a dozen kilometers, closer to the Russian border.

Summer escalation

Following the seizure of major cities in the Donbas from Russian/pro-Russian forces, these ostensibly local forces staged autonomy referendums and formed into political and military factions. These groups included the Russia-backed (and, in some cases, Kremlin-chosen) groups that would become the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, along with military units such as the Vostok Battalion. Along with the Ukrainian military, volunteer battalions were formed to support Ukraine, including some consisting of foreign fighters and some funded by oligarchs.

Donetsk Airport

While Ukraine was able to recapture cities on the edges of the frontlines, such as Sloviansk and Mariupol, it never regained control of the separatist strongholds of Donetsk, Luhansk, and other key cities. However, some key infrastructure near of the cities could recaptured by the Ukrainian army, leading to the airports of Donetsk and Luhansk becoming two of the most contested locations for the conflict. A new terminal had been constructed at the Donetsk Airport for the Euro 2012 football championship which Ukraine co-hosted with Poland, but this terminal and the rest of the airport became the staging ground for a battle that lasted over six months.

The control tower west of the terminal became a symbol for the Ukrainian forces, along with the so-called “Cyborg” soldiers who controlled segments of the airport before eventual separatist/Russian victory.

Mass Russian intervention

Through July, the conflict was tilting in the favor of Ukraine, with the recapture of key cities (Sloviansk, Mariupol) and advances towards separatist strongholds. Russia responded in two ways, successfully shifting the tide of the war: by sending a vast number of soldiers and military equipment through illegal border crossing points, and conducting a massive wave of artillery attacks from Russian territory onto Ukrainian military positions. In the comparison below, a field camp of the Ukrainian army just south of Amvrosiivka was covered with dozens of artillery impact craters.

By studying the shape of these impact craters by using a method developed by the U.S. Army and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, we can ascertain the trajectory of the shell and the firing site. This analysis reveals that the artillery that conducted this mass shelling was located south — towards the nearby Russian border. One of the firing sites is located in a field in Russia, about a kilometer from the border. There are five Grad-length firing sites left burned into the field, pointing towards the crater field in Ukraine.

Ukrainian air superiority and Russian response

One of the main reasons for Ukraine’s summer success was through its air force, though separatists managed to down several Ukrainian planes and helicopters with MANPADS. The power, and destructiveness, of Ukrainian air strikes can be seen in the July 15, 2014 attack in Snizhne, when a residential building at 14 Lenin Street was hit by a Ukrainian airstrike, leading to 11 civilian deaths. The Ukrainian planes were likely aiming for a separatist base and vehicle yard about 300 meters northwest of the attacked residential building. Shortly after the bombing, Ukrainian officials blamed Russian planes for carrying out the attack, but there is no evidence to support this. The damage to the apartment building at 14 Lenin Street is still visible in recent satellite imagery.

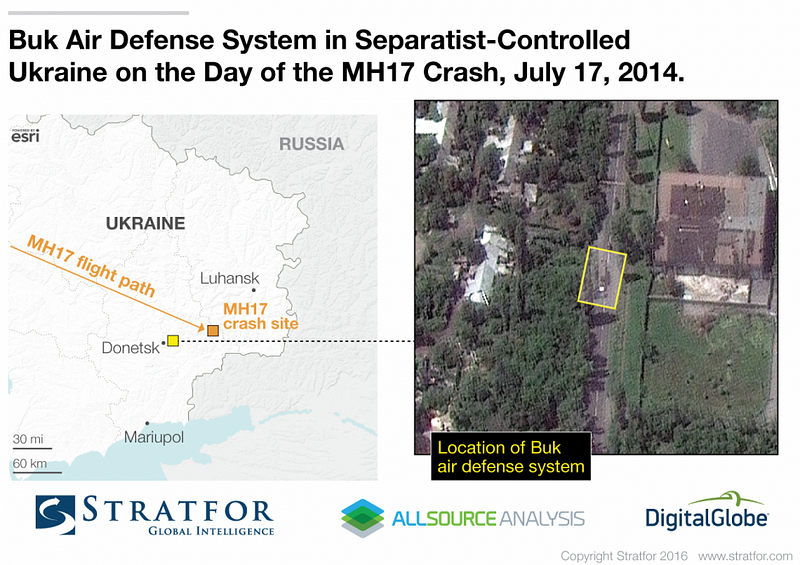

“Separatist” forces received direct Russian assistance to neutralize Ukrainian air superiority, most fatefully in a Buk-M1 TELAR sent to Donetsk on July 17, 2014. A Digital Globe satellite image from 11:08am that morning shows that Buk-M1 transported by a white Volvo truck, heading east towards Snizhne — where the attack on the apartment building happened two days previously.

The decision to send this Russian Buk-M1 system from the 53rd Anti-Aircraft Brigade to Donetsk-based separatists led to the death of 298 passengers and crew on Malaysian Airlines Flight 17.

The Guns of August

The advanced made by Ukrainian forces in the summer of 2014 was reversed in August, when Russia intensified its involvement in the conflict, including sending thousands of Russian servicemen with their tanks and artillery equipment to Ukrainian territory. Perhaps the largest staging area for Russian soldiers and equipment before crossing into Ukraine was the Kuzminsky firing range, located a bit under 50km from the Ukrainian border.

Many of these soldiers and tanks were involved in the Battle of Ilovaysk, one of Ukraine’s most devastating losses in the conflict. After partially taking, and then losing, control of Ilovaysk, Ukrainian forces were encircled by mixed separatist-Russian forces. Despite previous agreements for a “green corridor” for withdrawal, hundreds of Ukrainian soldiers were killed trying to break through the Russian encirclement. One of the fiercest battles took place near Chervonosilske, south of Ilovaysk. A comparison between satellite imagery on August 26 and August 30, 2014 shows the movement of military equipment and use of artillery shelling in the area:

In some cases, we can see the artifacts from the battle, including the remains of a Russian T-72B3 tank — a model of tank that is exclusively used by the Russian Armed Forces, and has never been exported.

Russian/separatist forces have controlled Ilovaysk since the defeat of Ukrainian forces in the area, giving them a key rail hub southeast of Donetsk. Current satellite imagery shows that separatists still operate a base in southwest Ilovaysk.

On September 5, 2014 the first Minsk agreement was sign, following Ukraine’s massive losses in the Battle of Ilovaysk, along with losses south of Luhansk and in the Battle of Novoazovsk. The ceasefire had some minor success after the tremendous violence of August 2014, but ultimately collapsed. Next week, we will continue this series by providing a brief history of the Ukrainian conflict from the negotiation of Minsk I until its collapse, marked most notably by the so-called “Second Ilovaysk”: the Battle of Debaltseve.