Target: Merkel

How the international far right mobbed the German Chancellor after the Berlinattack

Target: Merkel

Banner: Source: @prisonplanet / Twitter

Germany holds elections in late 2017. Analysts have already reported that Chancellor Angela Merkel is being targeted with fake news and online attacks, espceially from hyperpartisan and conspiracy sites. In this post, the DFRLab dives down into the details of one specific recent online attack to gain an understanding of how such mobbings work, and how they spread.

On December 19, 2016, at 20:02 local time (19:02 UTC), a Tunisian failed asylum seeker drove a truck into a crowded Christmas market on Berlin’s Breitscheidplatz, killing twelve people and injuring 56.

In the aftermath of the disaster, social media were flooded with posts about the Berlin attack. Many conveyed sympathy, but others launched a sustained personal attack on Chancellor Angela Merkel. Three days later, Bloomberg reported that Twitter trolls and automated “bot” accounts which had supported Donald Trump’s presidential campaign had joined the online mobbing.

A mobbing certainly took place, especially in English. However, digital forensic research shows that this was far more than just an attack by a network of “Trump bots”. Merkel was targeted by far-right and populist commentators from across Europe and America, spearheaded by a number of high-profile public figures.

Given the increasing media focus on the danger of trolling, fake news and online attacks ahead of the German election, the purpose of this article is to present detailed evidence of how one such attack unfolded.

More English, more hostile

The overall pattern of the mobbing reveals two significant characteristics: first, English-language posts far outnumbered other languages, including German; second, a far higher proportion of English-language traffic was hostile to Merkel.

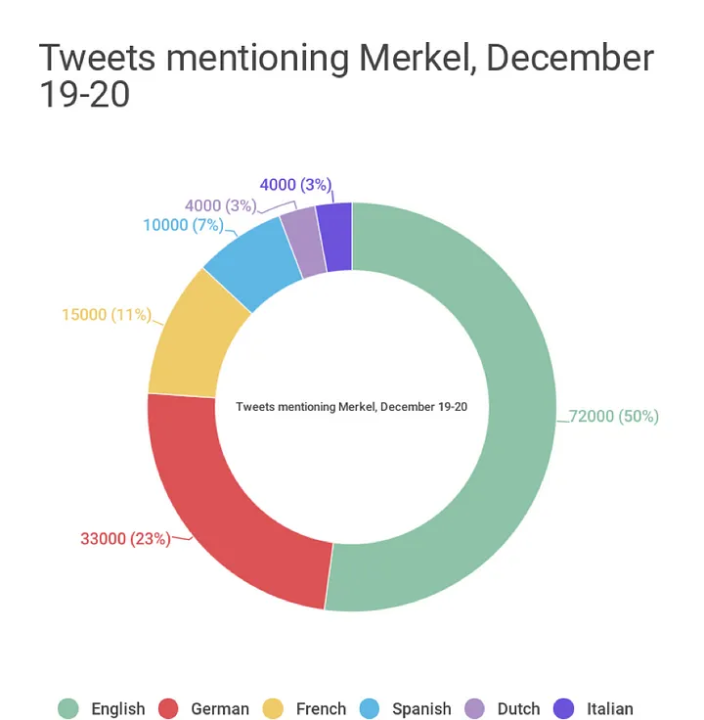

According to a machine analysis of the more than 140,000 tweets mentioning Merkel’s name between 19:00 UTC on December 19 and 12:00 UTC on December 20, half were in English, less than a quarter were in German, and the rest were a mixture of other languages.

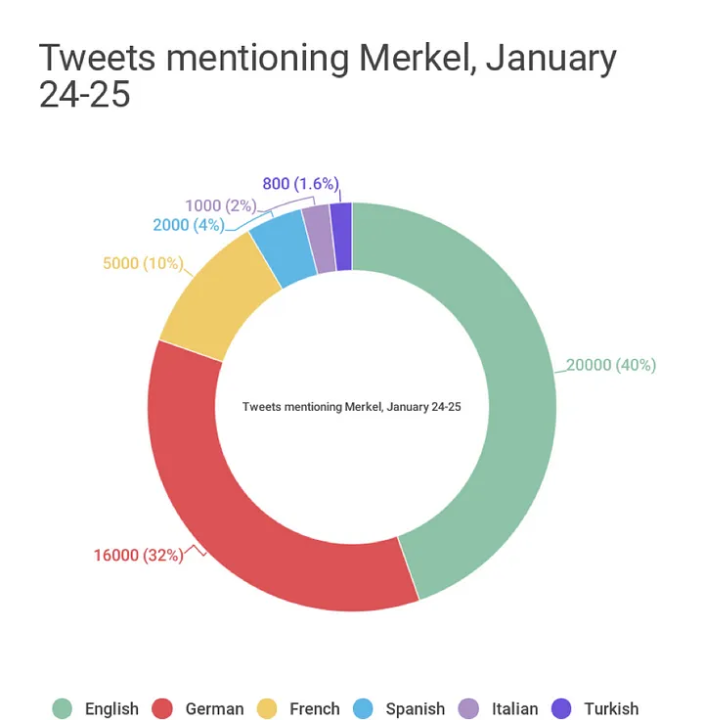

This can be compared with a control sample of 50,000 tweets naming Merkel on January 24–25, in which the proportion of English and German tweets was much closer:

On December 19–20, over 2,700 tweets using the name “Merkel” also mentioned the English word “resign” (3.75%). Just 700 used the equivalent German verb “zurücktreten” or the noun “Rücktritt” (2.1%), and one of the very earliest was an English nationalist account. It was English users, not German ones, who spearheaded the call for Merkel to step down.

Rapid reaction: balanced in German…

Individual posts confirm that larger pattern. Users in many languages began blaming Merkel in the minutes after the attack, but English-language posts were significantly more numerous and aggressive.

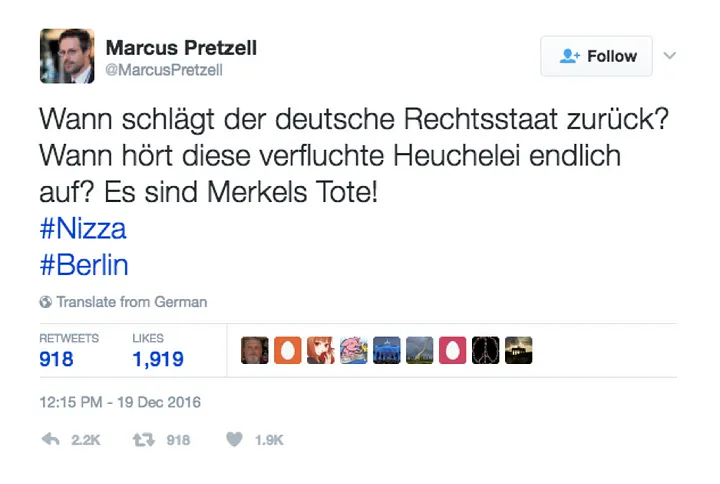

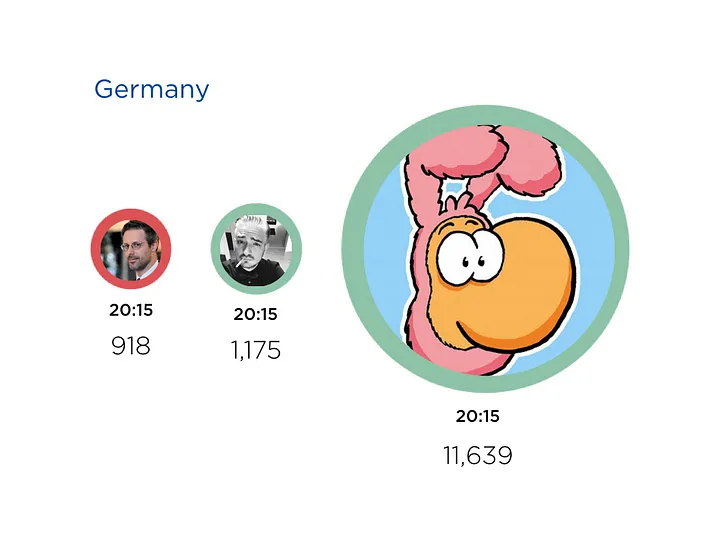

In the 90 minutes after the attack, the most-shared anti-Merkel post in German came from Marcus Pretzell, a Member of the European Parliament for the populist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party:

“When will the German state based on the rule of law strike back? When will this accursed hypocrisy finally end? They are Merkel’s dead! #Nice #Berlin.”

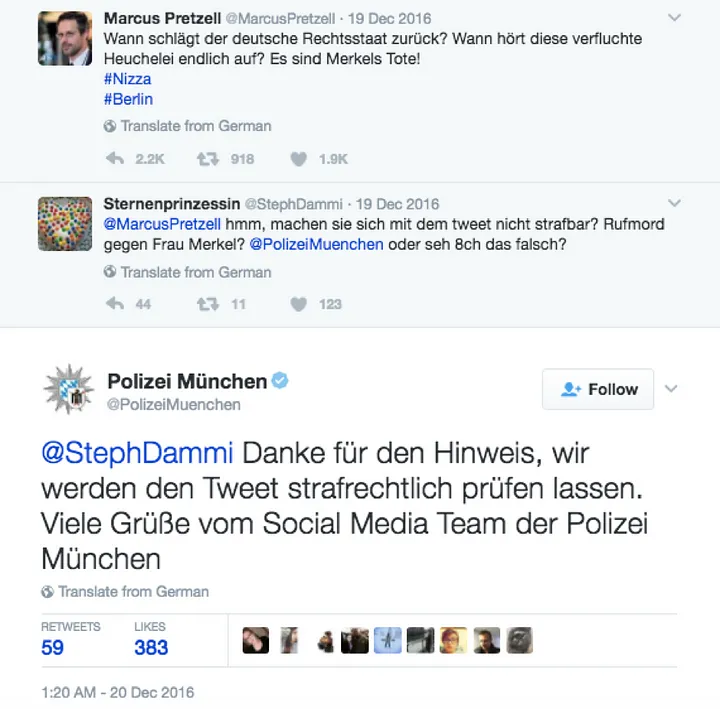

Pretzell’s tweet achieved some penetration, with 918 retweets. However, it was also criticized online, with one user forwarding it to the Munich police with the question of whether it was legal, and the police replying that they would investigate:

@StephDammi: @Marcuspretzell, hmm, aren’t you laying yourself open to prosecution? Character assassination against Mrs Merkel? @MunichPolice or am I looking at it wrong?

@Munichpolice: @StephDammi Thanks for the tip, we will have the tweet checked against criminal law. Best wishes from the Munich Police Social Media Team

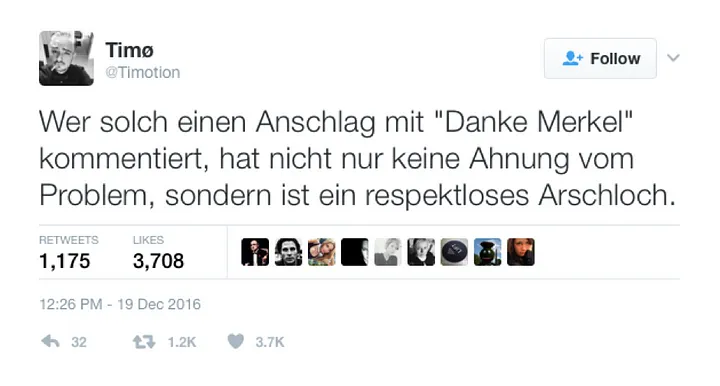

By comparison, an almost simultaneous tweet which defended Merkel and attacked her critics was retweeted 1,175 times:

“Anyone who comments on such an attack with ‘Danke, Merkel’ not only has no idea of the problem, but is a respectless arsehole.”

… unbalanced in English

In English, the conversation was heavily dominated by Merkel’s accusers. Most of these were pro-Trump and / or far-right accounts in the US and UK.

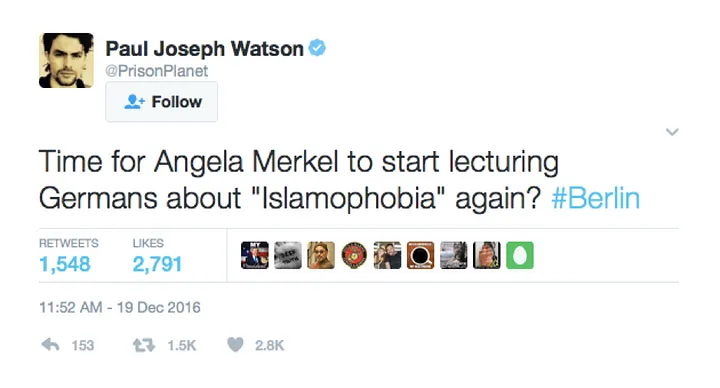

In the first 90 minutes after the attack, all of the most-shared English-language tweets were hostile. The top was a tweet from self-styled “contrarian polemicist” Paul Joseph Watson, who speculated that the attack was “time for Angela Merkel to start lecturing Germans about ‘Islamophobia’ again”. The tweet was retweeted 768 times between 19:52 and 21:00 — an average of once every six seconds.

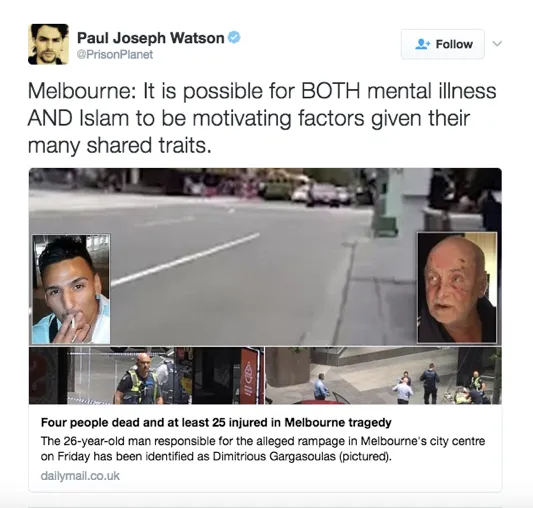

Watson is editor-at-large of controversial fringe US outlet “Infowars”, which espouses anti-Islam views and conspiracy theories such as “Pizzagate”. Watson uses the pejorative “libtards” (short for “liberal retards”) to refer to less right-wing commentators and voters, and has compared Islam with mental illness and called for the Qur’an to be banned as hate speech.

The second most popular tweet was from a British account attributed to controversial Northern Irish blogger David Vance, portraying Merkel in Muslim garb:

Vance, too, uses a pejorative for the political left (“leftards”, in this case), is outspokenly pro-Brexit and aggressive towards those who opposed it, and has compared Islam with a mental illness.

The third was from English nationalist account @DavidJo52951945, which reported on the attack with the phrase “Happy now, Merkel?” This account combines aggressive pro-Brexit rhetoric with attacks on liberals, and has called for Islam to be banned.

The account has repeatedly trolled Merkel with the phrase “happy now?” in contexts such as the terrorist threat against a Germany-Netherlands soccer match, and reports of rapes and murders by refugees.

The fourth was from a US-based account, @TEN_GOP, calling on Merkel to “clean up the blood herself and then step down”.

The @TEN_GOP account is primarily pro-Trump. It was created in November 2015, and shares the use of the epithet “libtard”, anti–Islam and anti-migrant posts. It also has a history of sharing fake news, such as the false claim that Hillary Clinton advisor Sidney Blumenthal blamed her for the death of US diplomats in Benghazi.

The fifth was another tweet from Vance, saying, “I remember being at the Berlin Christmas markets a few years back. Very nice. That was BEFORE #Merkel opened up Germany to Islamic invasion”.

Together, these five tweets were retweeted over 1,500 times between 19:30 and 21:00, accounting for almost one-sixth of all the English-language traffic about Merkel in that period.

All through the night

During the night, positive messages came to dominate the overall Twitter conversation about Merkel. However, anti-Merkel and far-right sentiment continued to dominate the English-language space.

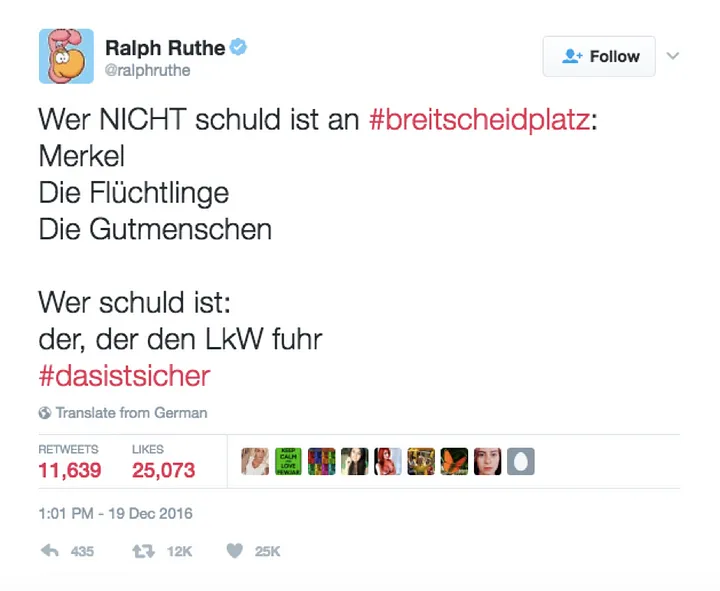

Between 21:00 on December 19 and 10:00 on December 20, the single most popular tweet came from German cartoonist and film maker Ralf Ruthe, rejecting the claim that anyone but the truck driver was to blame:

Who’s NOT to blame for the #breitscheidplatz: Merkel, the refugees, do-gooders. Who’s to blame: the one who drove the truck. #that’sforsure

His tweet was retweeted 8,652 times before 10:00, the single most popular tweet about Merkel in any language by some margin. The second most retweeted post was a message of condolence and solidarity from French President François Hollande, with over 2,500 retweets.

The picture in English was different: as before, all the most-shared posts which used Merkel’s name attacked her.

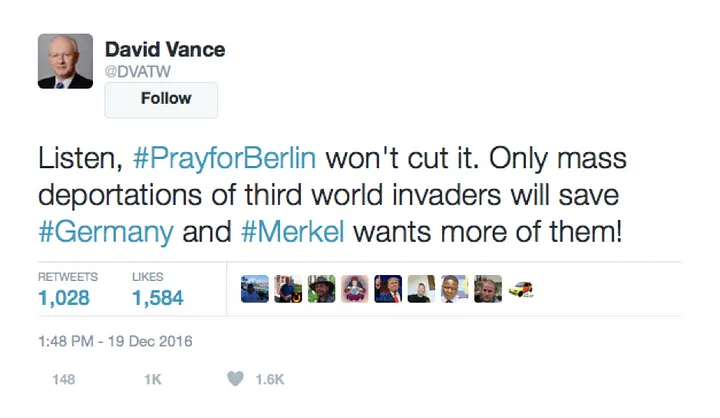

Watson and Vance both contributed, with Watson demanding Merkel’s instant resignation and Vance calling for “mass deportations of third world invaders”.

They were joined by both US- and UK-based accounts. In the US, hostile posts came from alt-right users such as @BrittPettibone, who tweeted “Wake up, Germans. Reject Merkel, reject ISIS and take a stand in defense of the country you call home”, and @amymek, who tweeted, “Merkel signed her own citizens death certificates by allowing Muslim Invaders while Germans Fools welcomed their new muslim masters!”

@Amymek is another serial Merkel attacker, who tweeted almost exactly the same phrase on January 7, July 24 (adding the word “#Trump”) and December 6.

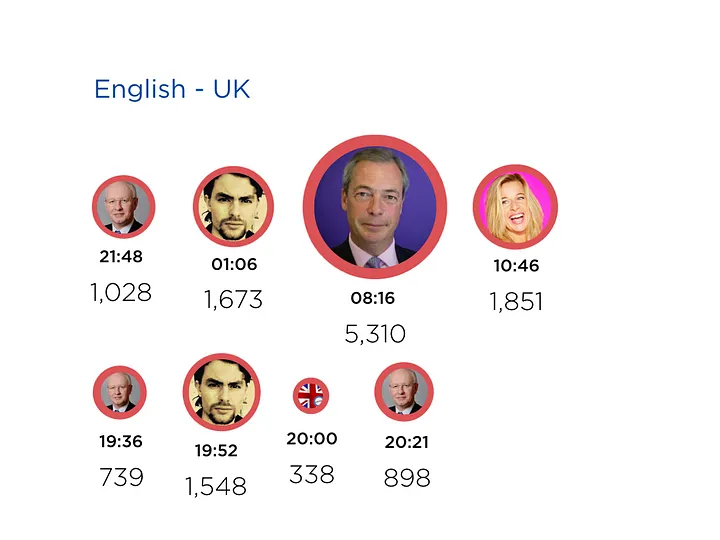

Chief among the UK posters was anti-EU leader Nigel Farage, who tweeted, “Terrible news from Berlin but no surprise. Events like these will be the Merkel legacy.”

Another was Daily Mail commentator Katie Hopkins, who tweeted on the issue several times. Her most retweeted post ran, “That’s lovely. Merkel was at a ceremony honouring migrants whilst one of her pet asylum seekers mowed down 12 German nationals.”

By noon on December 20, the tweets from Farage and Hopkins were the most retweeted in English, being shared over 1,600 times between 10:00 and 12:00.

Populist and far-right leaders joined the mobbing in other languages. However, they scored less success than their English-language peers.

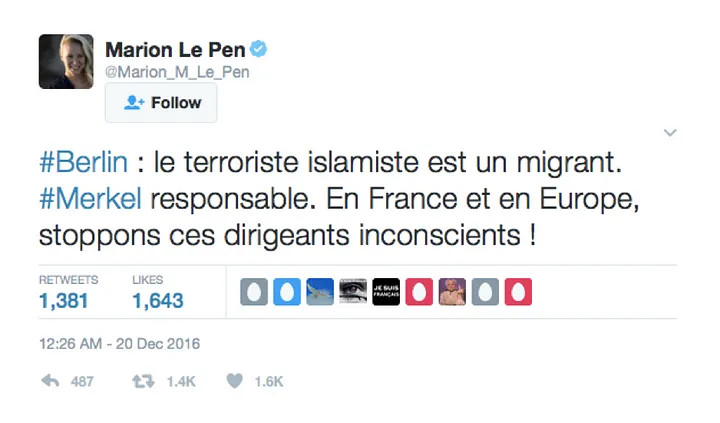

Dutch anti-Islam populist Geert Wilders tweeted to accuse “Merkel, Rutte and the other cowardly government leaders” of letting in “the asylum tsunami and Islam terror with their open border policies”. French far-right politician Marion Marechal Le Pen tweeted in French that “Merkel is responsible”.

#Berlin: the Islamist terrorist is a migrant. #Merkel responsible. In France and in Europe, let’s stop these foolhardy leaders!

Wilders’ was the most shared Dutch tweet to mention Merkel overnight, with a modest 387 retweets by noon; Le Pen had 660 retweets by noon, well behind Hollande.

Attackers and amplifiers

The mobbing of Merkel was clearly a predominantly English-language phenomenon. However, it would be inaccurate to give it a single label, such as “pro-Trump” or “far-right”. The mob, if such it can be termed, included accounts from a variety of backgrounds and with a variety of priorities.

Some were primarily Trump supporters, notably @TEN_GOP. Others came from far-right accounts whose support for Trump appears the consequence of other positions. Still others stemmed from anti-EU and anti-Islam personalities, notably Wilders, Farage and Le Pen, who appear to have used the Berlin attack to score political points at home.

A similar pattern applies to the accounts which amplified these leading voices. A number appear to be automated bots or semi-automated cyborgs, posting hundreds of times a day, with 95 percent or more of their posts as retweets. However, the accounts are not uniform in their language or obsessions.

Some of the likely bot accounts focus on US politics, amplifying Trump and the US far right; others focus on German or French politics, and post primarily in those languages. Many other accounts show bot-like levels of activity, posting hundreds of times a day, but with a greater or lesser proportion of original content, indicating the intervention of a human user.

The likelihood is, therefore, that the mobbing of Merkel was driven by a combination of bots, semi-automated accounts and genuine users with a number of interlocking agendas.

It is also highly likely that such mobbings will continue. The online events of December 19–20 reveal that Merkel is now a prime target, if not the prime target, for far-right, populist, anti-EU and anti-Islamic groups on both sides of the Atlantic.

The attacks are driven by high-profile public figures, and amplified by a network which includes a mixture of bots, cyborgs and activists. So far, they have penetrated much more widely in English than in German; how long that will last is an open question.