France holds presidential elections on April 23. Ahead of the polls, reports are emerging of sophisticated online groups supporting some of the candidates, especially far-right leader Marine Le Pen.

According to the Financial Times, Le Pen is supported by “an aggressive social media operation that is the most powerful in French politics”, putting her at the forefront of social media campaigning.

The operation is certainly aggressive, slick, and well coordinated. But research reveals that it is also small, driven by a handful of key accounts and a network of hyperactive followers, many of which appear to be automated.

The pro-Le Pen social media operation is therefore a case study in how a small group of users can use (or abuse) Twitter to make themselves appear far more numerous than they really are.

“Patriot” games

In the second half of February, a group of Le Pen supporters online launched three “patriot” hashtag campaigns — two supporting her, and one attacking her main challenger, centrist Emmanuel Macron.

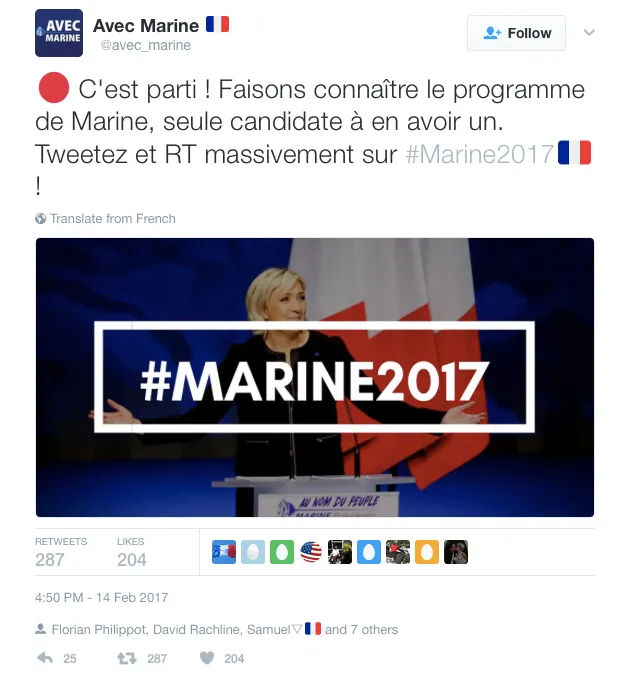

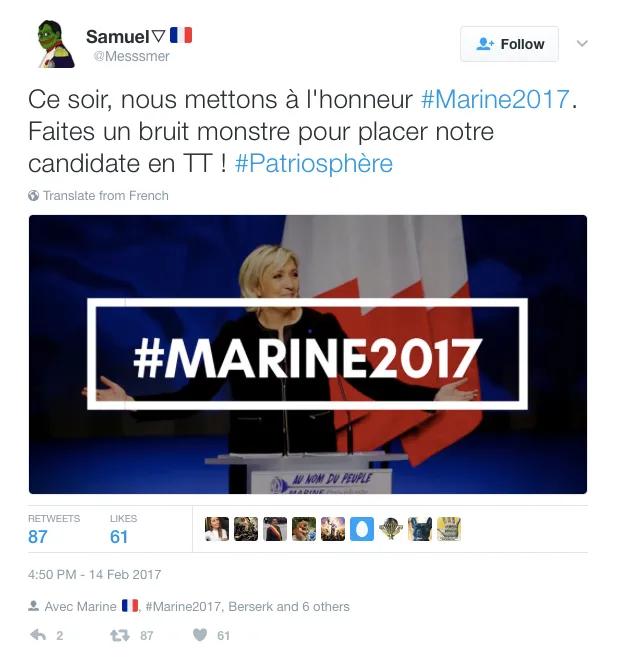

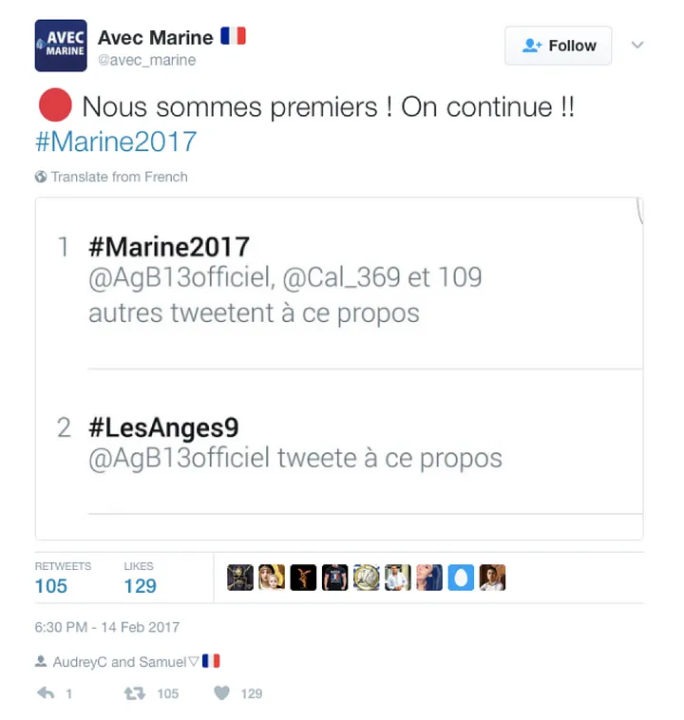

The first, on February 14, pushed the hashtag #Marine2017:

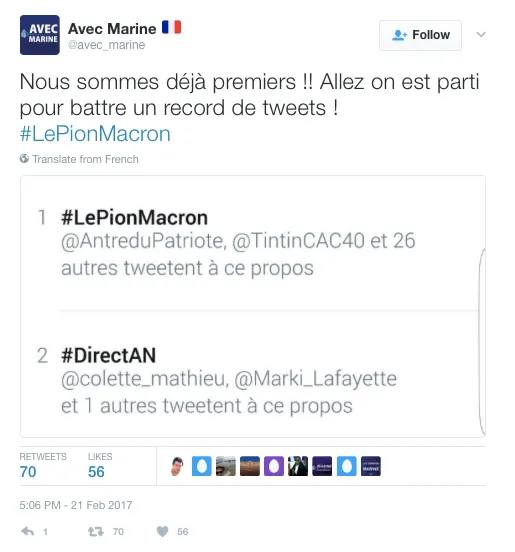

The second, a week later, portrayed Macron as a pawn of “le système”, under the hashtag #lepionMacron (literally “the pawn Macron”). The third, on February 26, launched the hashtag #LaFranceVoteMarine (“France votes for Marine”).

The goal of all three campaigns was to make the hashtag trend, moving it out of the circle of far-right followers and bringing it to the attention of general Twitter users.

According to their own claims, the hashtags did indeed end up trending:

How was this achieved?

Leaders of the pack

Each campaign started with a burst of simultaneous tweets from a handful of key accounts. The most obvious example is the first.

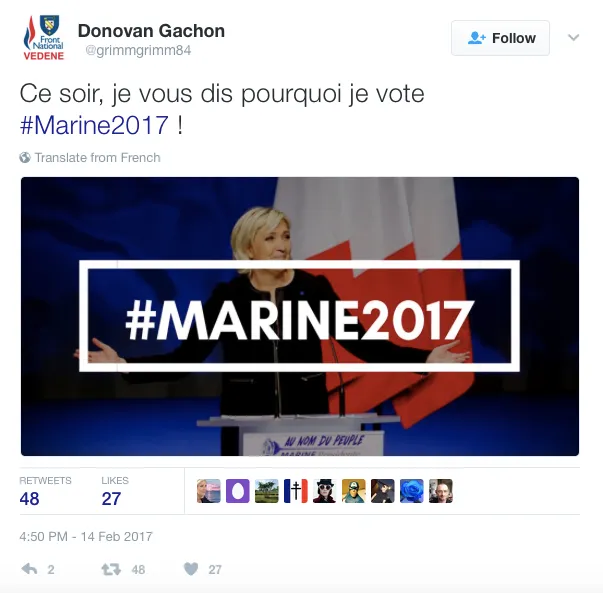

On February 14 at 16:50:03 UTC, an account handled @grimmgrimm84 launched the #Marine2017 campaign with an image of Le Pen:

One second later, two other accounts, @avec_marine and @messsmer, tweeted the same image, but with different texts. Both are reproduced above.

This simultaneous use of the same image with different texts clearly shows that the three accounts had coordinated their posts. A similar pattern followed on February 21, with the launch of #LePionMacron.

This time, @avec_marine was the first to post, at 16:50:03, with the caption, “I invite you to tweet and RT massively: #LePionMacron. Macron is the pawn of the system!”

@Messsmer was slightly slower off the mark, tweeting the same image at 16:50:25, with the caption “Manipulation is finished! Let’s put #LePionMacron into the Top Trends to unmask this person!”

Within fifty seconds, three other accounts, @KimJongUnique, @AudreyPatriote and @AntreDuPatriote, had tweeted the same image with their own messages.

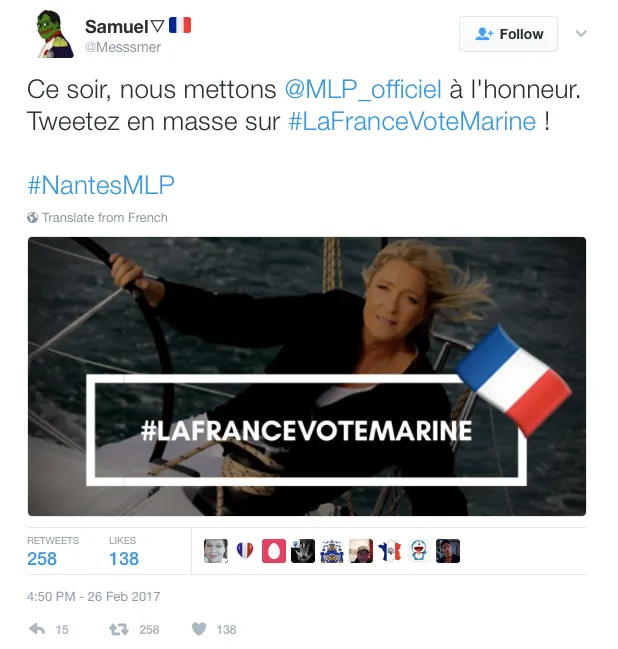

Exactly the same accounts launched the #LaFranceVoteMarine campaign on February 26. In this case, @messsmer was first, posting at 16:50:00 to say, “This evening, we’re honoring @MLP_Officiel. Tweet en masse on #LaFranceVoteMarine!”

@avec_marine posted eleven seconds later. This time, the account used a different image, but in the same style:

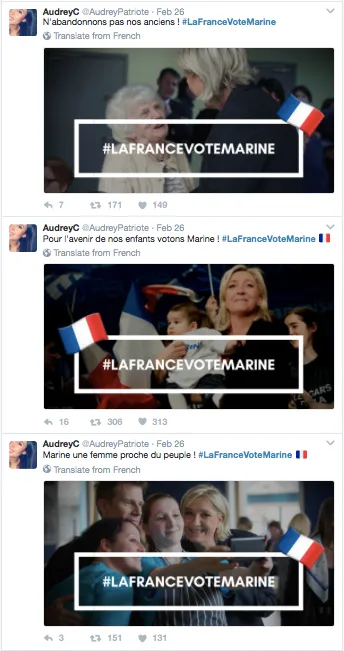

In the following minute and a half, @antredupatriote and @audrey_patriote tweeted the same hashtag, using different memes, but in the same style:

Thus, the same handful of accounts, led by @avec_marine and @messsmer, initiated all three hashtag campaigns.

Coordinated memes

The scale of the campaigns’ preparation becomes apparent when examining the memes these accounts and their amplifiers shared.

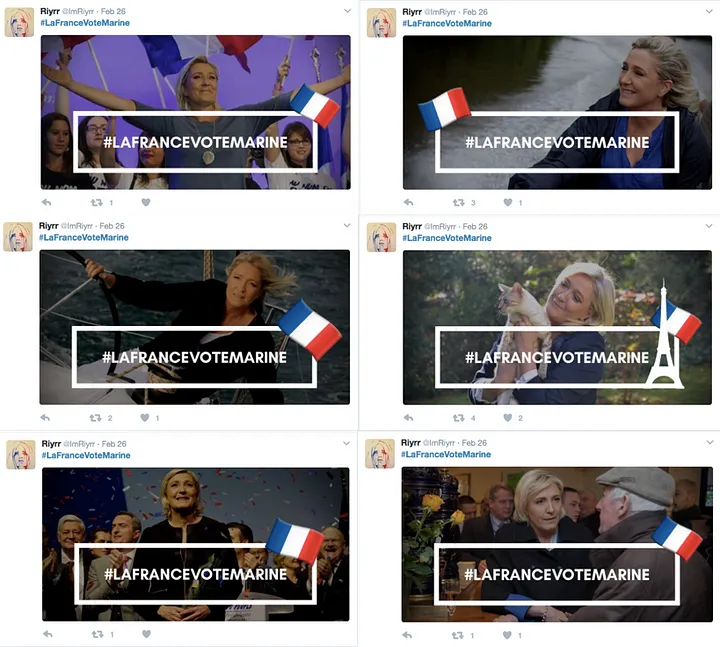

The #LaFranceVoteMarine campaign is the clearest case. As noted above, the primary accounts simultaneously tweeted four different images in the same style. Over the following hour, @messsmer tweeted all four, and another eight besides, precisely five minutes apart. @Audrey_Patriote tweeted eleven, ten of them the same as @messsmer’s, at more irregular intervals. Another account, @ImRiyrr, also posted a dozen, the same set as @messsmer’s; six are captured here for comparison:

This use of a stock of prepared images was not a one-off occurrence. @ImRiyrr’s posts on February 14 even more obviously betrayed an entire deck of pre-planned memes.

The purpose of the #Marine2017 campaign was to publicize Le Pen’s election manifesto. During the first hour, the lead accounts tweeted a number of extracts from the manifesto as colored tiles:

In total, @messsmer posted fifteen such tiles; @avec_marine posted eight; @grimmgrimm84 posted twenty-five. A few of the posts were common to all of them, but most were not.

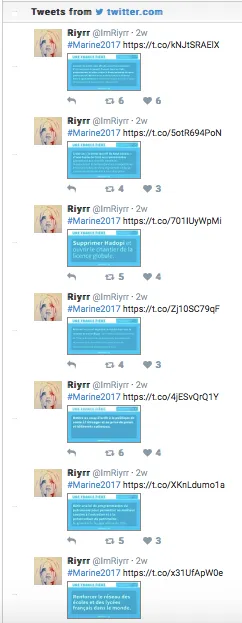

The stock of tiles was far bigger than this, however. Between 18:04 and 18:21, @ImRiyrr posted ninety-five different tiles of Le Pen’s pledges. None was accompanied by any text other than the hashtag:

Perhaps as an indication that this coordinated use of a prepared stock of memes was meant to be kept secret, @ImRyirr’s tweets themselves have since been deleted; however, the images themselves have all been archived (samples here, here, here and here).

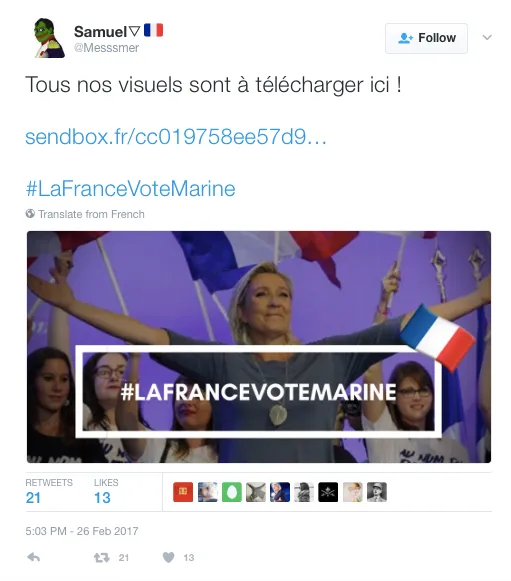

This storm of 95 meme-tweets in 17 minutes, each with nothing but a hashtag and a picture, demonstrates two things. First, it reveals the practice of preparing a huge stock of memes in advance. That was further confirmed on February 26, when @messsmer tweeted a link to an online store of images:

Second, it indicates that @ImRiyrr is an automated “bot” account, used to amplify the hashtag and memes.

Penetration through automation

In fact, @ImRiyrr is by no means the only automated account to have taken part in the hashtag campaigns. A number of factors indicate that the campaigns owed their online penetration to automation.

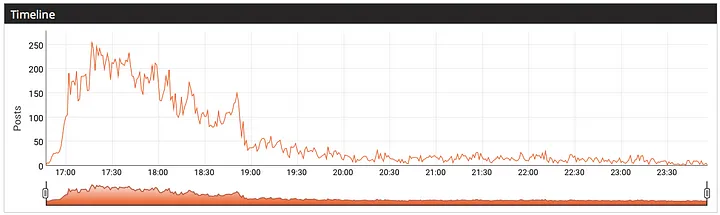

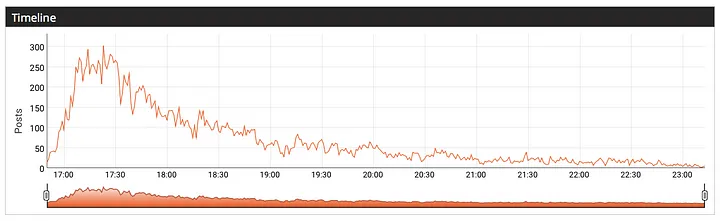

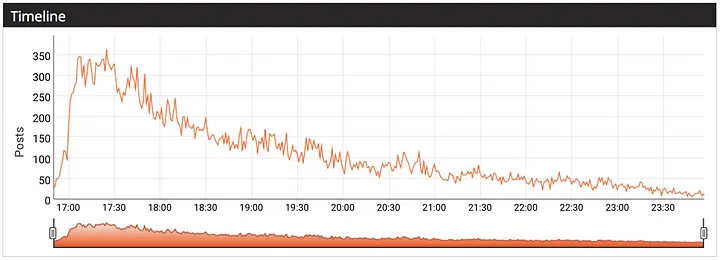

Firstly, all three campaigns — each of which launched at 16:50 UTC, 17:50 French time — featured explosive spikes in Twitter traffic in the first half-hour of the campaign, and a rapid decline thereafter.

This is characteristic of a campaign using a set of automated accounts for a set period, rather than a grassroots campaign in which users’ engagement grows over time, peaks and then slowly declines.

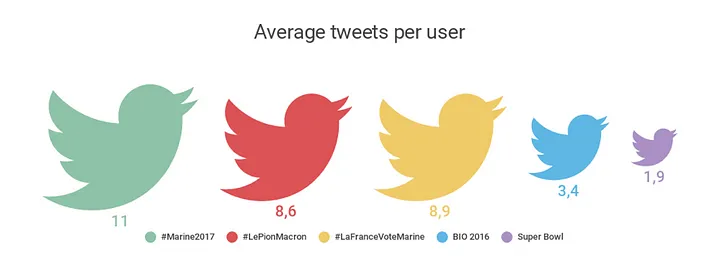

Secondly, the campaigns featured a very high average number of tweets per user. According to a machine scan of the February 14 campaign, 1,104 users posted 12,237 tweets using the hashtag #Marine2017 between 16:50 and 18:00. That translates into an average of 11 tweets per user in the first hour.

On February 21, during the first hour of tweeting, the equivalent average was 8.6 tweets per user; it rose slightly to 8.9 per user on February 26.

This is remarkable. For comparison, a controlled sample of an unrelated “general-interest” event — the 2017 Super Bowl — collected 1.5 million tweets from over 800,000 users, at a rate of 1.875 per user. A sample from a specialist biology conference in December 2016 recorded an average of 3.4 tweets per user, out of 24,000 tweets.

Thus, the explosive growth of the Le Pen hashtags was caused by a group of unusually dedicated users tweeting many times each.

Hyperactive users

That impression is confirmed by an analysis of the pattern of users. A high proportion of the traffic on these hashtags was generated by a relatively tiny number of accounts — a few dozen at most — which tweeted with inhuman rapidity, artificially amplifying the posts from the key accounts.

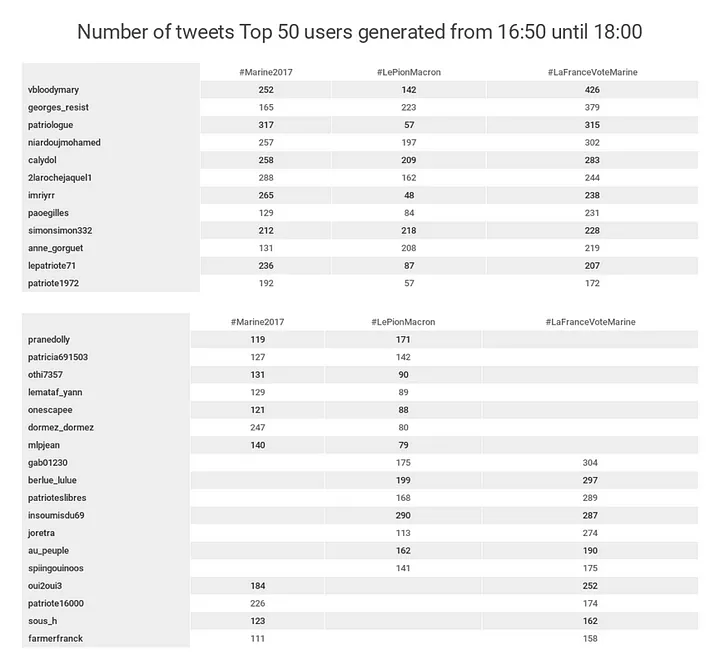

The account @2larochejaquel1, for example, posted 288 tweets in the first hour and ten minutes of the #Marine2017 campaign, at a rate of one every 16 seconds. All were retweets. @Vbloodymary posted 252 over the same period, almost all retweets; @calydol posted 258, all retweets; @NiardoujMohamed posted 257, almost all retweets.

This combination of sustained hyper-tweeting and an emphasis on retweets suggests that these are either automated bots or semi-automated “cyborgs”, designed specifically to post large numbers of tweets.

Moreover, while some of the accounts which amplified the campaign belonged to verified users, especially far-right politicians, a very high proportion of posts in the first hour came from unverified, and probably automated, accounts.

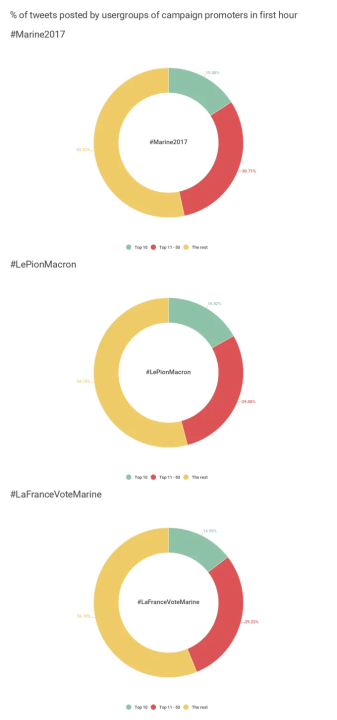

For example, the ten most active users of the #Marine2017 hashtag posted 1,971 tweets in the first hour — 16 percent of all the tweets posted. The top 50 users posted 5,713 tweets, or 47 percent of the total.

The same held true of the #LePionMacron and #LaFranceVoteMarine campaigns. In both, the top ten users accounted for around 15 percent of posts in the first hour, while the top fifty accounted for around 45 percent.

Again, this indicates a small and hyperactive group of largely automated accounts driving a hashtag through the sheer volume of their retweets — rather than an organic, grassroots campaign.

Active leaders, active amplifiers

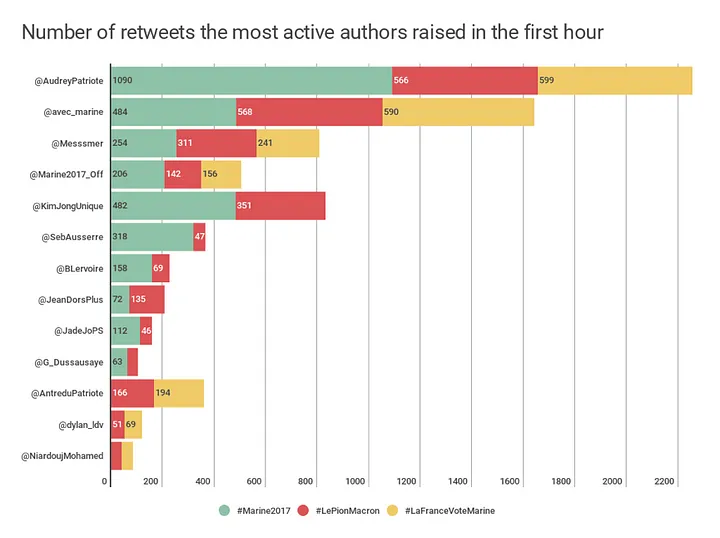

However, the leaders did not simply rely on massive automated retweeting to achieve an effect: they were very active themselves, posting numerous tweets of their own, and retweeting one another.

This gave the amplifier accounts a large amount of material to retweet, without making the pattern so obvious that it would trigger bot-detection algorithms.

The @messsmer account, for example, posted forty-five tweets on #LaFranceVoteMarine between 16:50 and 18:00 on February 26. Of these, thirteen were memes, the other thirty-two were retweets, including of fellow leaders @AudreyPatriote (four times) and @AntreduPatriote (four times), and even, once, himself.

AudreyPatriote posted eight different memes over the same period, as well as retweeting @avec_marine:

Supporting them, the amplifier account @NiardoujMohamed retweeted @Messsmer twelve times in the hour and @AudreyPatriote six times. The amplifier @georges_resist retweeted @AudreyPatriote seven times and @Messsmer five times; @Vbloodymary retweeted each five times.

With support such as this, the key accounts were able to rack up impressive numbers of retweets:

Effect and counter

The combination of active leaders and hyperactive amplifiers had an effect: according to their own account, all three hashtags made it into the top trends.

It is instructive to note that in the above tweet, @avec_marine tagged two other users, namely @Messsmer and @AudreyPatriote, confirming the live coordination between the leading members of the group.

This indicates the extent to which a small group of users, with sufficient material and sufficiently active amplifiers, can break into the top trends.

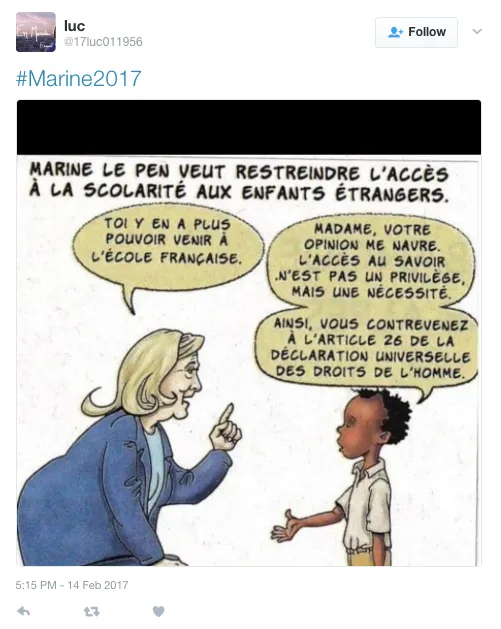

The traffic, and the use of automation, was not all in one direction. One of the top tweeters on #Marine2017, with 231 tweets before 18:00, was called @17luc011956, a pro-Macron account which attempted to hijack the hashtag with a mixture of pro-Macron and anti-Le Pen memes:

The alphanumeric account handle, its one-sided tweeting, its lack of any personal features, its hyperactivity and its plentiful use of memes indicate that this is a pro-Macron cyborg, also backed by a stock of memes. However, it achieved no retweets or mentions in the first hour, and failed to disrupt the spread of the hashtag.

Conclusion

The social media operation supporting Le Pen is, indeed, sophisticated, aggressive and well prepared. It also appears to be effective, driving its hashtags to the top of the trends through the use of large quantities of material and a significant number of automated accounts.

However, it is also small. All three campaigns were launched by the same handful of accounts, and amplified by a consistent group of hyperactive supporters. They owed their effect not to massive online support, but to the calibrated use of automated accounts, active enough to make the hashtag trend, but not so active that they were detected.

Above all, they were shortlived. None of these “patriot” actions achieved an impact on Twitter beyond the initial spike: they faded away within hours of being launched. Le Pen’s online army is not a grassroots movement, but a small group trying to look like one.