Busting Fakes, Kremlin Style (Part 1)

Fact checking the Russian Foreign Ministry’s “fakes” page

Busting Fakes, Kremlin Style (Part 1)

BANNER: Source: Russian Foreign Ministry “unreliable publications” page

In this, the first of two reports, the @DFRLab analyzes the Russian Foreign Ministry’s attempt to expose “fake” news reporting. The second report will analyze a similar project by Kremlin broadcaster RT.

On February 20, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched a section on its website aimed at exposing articles that contain “untrustworthy” information about Russia.

The Ministry’s approach was uncompromising: each article was labeled with a large red stamp saying “FAKE”. The URL for the section was set as https://www.mid.ru/en/nedostovernie-publikacii. “Nedostovernie publikacii” (недостоверные публикации) means “unreliable publications”.

In the first month of the project, eleven articles were stamped as fakes. All of them came from Western outlets; nine were in English.

The DFRLab has fact-checked the Ministry’s analysis of all eleven stories to see whether they can legitimately be called fakes.

As this report will show, they cannot.

Fake or mistake?

“Fake news” is a much-used, and much-abused, term which came into vogue during the 2016 US presidential election.

The term has not been clearly defined; however, linguistically speaking, “fake news” could be taken to mean “deliberately presenting false information as news.” This article will work on the basis of that definition.

Two key considerations arise from the definition. First, deliberately reporting untrue news is one of the most serious allegations that can be made against a news organization. For that reason, the standard of evidence must be high.

Second, the question of intention is important. A news article cannot be called “fake” simply because it misreports the facts: journalists are no more immune to mistakes than any other professional. For the “fake” label to be credible, the accuser must explain why the story should be considered a deliberate lie, rather than an error.

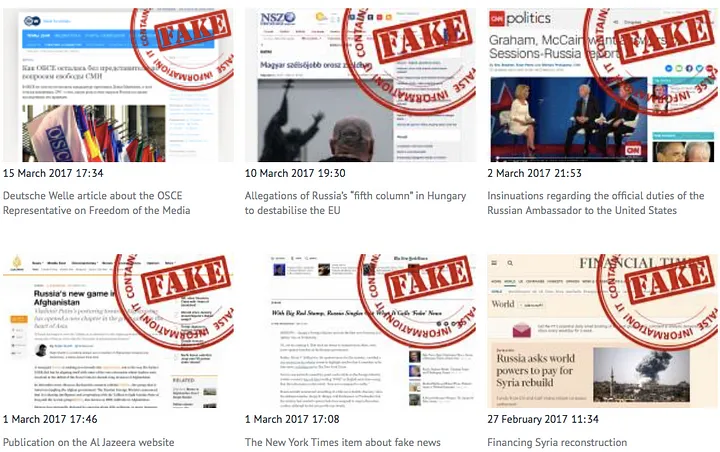

Examples of the standard of detail required to expose false media claims can be found, for example, in this DFRLab article on the number of US tanks deployed to Europe; this post from StopFake on claims that Ukrainian soldiers crucified a boy in Ukraine; and this Bellingcat report on the bombing of a hospital in Aleppo.

Start with a failure

Unfortunately for the Russian Foreign Ministry, the standard of evidence it initially offered was non-existent.

The first offering, on February 20, was a collection of four articles, one each from NBC News, the Daily Telegraph, the New York Times and Bloomberg. A piece from the Santa Monica Observer followed on February 22.

Each was labeled with a large red stamp reading, “FAKE: false information it contains,” the comment, “This article makes false assertions,” a link to the original and a screenshot of the article.

That was the full extent of the analysis.

No evidence was offered to show why the stories had been labeled “false information,” “bogus propaganda,” or “fake news” — three terms used by Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova when she presented the initiative.

The attempt was ridiculous, and ridiculed. Genuine fake-busting site StopFake tweeted advice on “How to fight fakes like the Russian MFA.”

МИД России решил не только производить фейки, но и "бороться" с ними. Для настоящего фактчекинга есть #StopFake: https://t.co/nEChQBVOYo pic.twitter.com/jbqhkc3Syl

— Stop Fake (@StopFakingNews) February 22, 2017

Parody account SovietSergey characterized it as the “fastest way to debunk ‘fake’ news.”

We at @mfa_russia have invented the fastest way to debunk "fake" news, we just say it's fake without proving it. https://t.co/74GjtXJgUZ

— Soviet Sergey (@SovietSergey) February 22, 2017

New York Times correspondent Neil MacFarquhar wrote on February 22, “Russia appears to be labeling as fake any articles it dislikes.” Given the importance of evidence in debunking false news, and the Ministry’s utter failure to provide any, these criticisms were entirely justified.

Inaccurate accusations

Apparently stung by the criticism, the Ministry began providing some textual commentary to accompany its now-infamous “Big Red Stamp.” For example, on March 1 the rebuttals page included two new entries, condemning MacFarquhar’s New York Times piece of February 22 and an opinion piece on the Al Jazeera website. Two weeks later, an article from the Deutsche Welle Russian service was added to the list.

These accusations were longer — they could hardly be shorter — but they were no more convincing. The Ministry accused Al Jazeera of misquoting Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on the issue of sharing intelligence with the Taliban:

The author, Najib Sharifi, claims that Russia is collaborating with certain terrorist groups, in particular the Taliban movement. The journalist cites Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, who allegedly stated that Russia is sharing intelligence with the Taliban in fighting the Islamic State (a terrorist organization banned in Russia). This is an outright lie; Mr Lavrov has said nothing of the kind.

However, the version of the Al Jazeera article the Ministry references did not even mention Lavrov; nor did the earliest known archive version, which was saved on February 26 at 13:01:02, the same day the article was published and three days before the Ministry’s rebuttal.

Moreover, the claim of Russia sharing intelligence with the Taliban was first reported in December 2015, when Russian outlet Interfax quoted Russia’s special envoy to Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, as speaking of “communications channels for exchanging information” with the Taliban. The Washington Post confirmed the quote.

Thus the Ministry’s accusation of an “outright lie” was, itself, false.

The New York Times article was the subject of two explicit accusations and one implicit one:

First, it deliberately distorts Russia’s position. And second, it does not even mention, let alone objectively analyze similar projects by Euro-Atlantic organizations. (…) We hope The New York Times will hear our opinion and will put forth our position objectively and in detail in its articles about the Russian Foreign Ministry.

The charge of not analyzing “similar projects by Euro-Atlantic organizations” is irrelevant: MacFarquhar’s article was a news report on the Ministry’s launch of its fake-busting page, not global fake-busting efforts. This leaves the accusations of deliberate distortion and failing to report the Ministry’s position “objectively and in detail.”

Neither stands up to the evidence. MacFarquhar quoted Zakharova at length, reporting her comments in seven paragraphs out of a twenty-eight paragraph piece. A comparison of his quotes with the Ministry’s transcript shows only the degree of variation which is to be expected of two distinct translations into English of the Russian original.

There was no distortion, and the Ministry’s position was given in detail. All MacFarquhar did was to hold the Ministry’s words up against its actions — notably, its use of the “fake” label without a shadow of evidence. This was not fake journalism: it was good journalism.

Thirdly, the Ministry took exception to a Deutsche Welle Russian Service article on the OSCE’s failure to appoint a new Representative for Freedom of the Media in both 2016 and 2017. Two main claims were made: that Deutsche Welle “did not cite any quotation” from a March 2016 Russian statement on the issue, and that it did cite an EU statement from the same period, but omitted to point out that it referred to the 2016 process, “in the best traditions of fake news.”

“Deutsche Welle obviously had no intention of writing the truth,” the Ministry wrote.

But the Deutsche Welle article to which the Ministry provided a link did cite the Russian statement, and correctly dated the EU comment:

On the evidence provided by the Ministry itself, the article was accurate; the Ministry was not. The question, therefore, is not whether Deutsche Welle had any intention of writing the truth, but whether the Ministry did.

Criticism and “fakes”

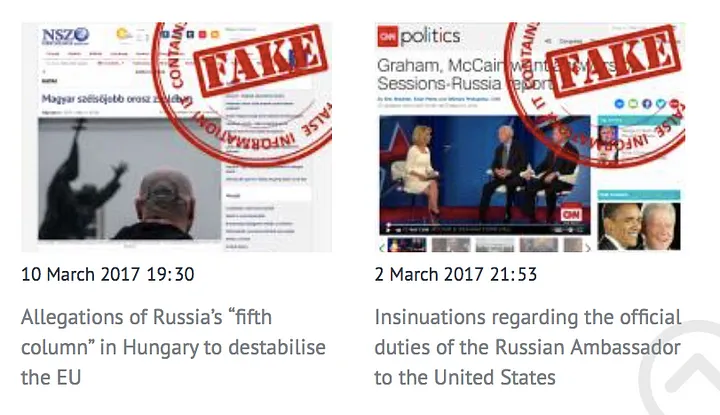

Overall, the Ministry appears to have been unable to distinguish between fakes, criticism, and statements it disagrees with. This can be seen from the final three accusations, leveled at the Financial Times, CNN and Hungarian daily Nepszáva.

The Financial Times quoted “European diplomats” as saying that Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister had said Syrian reconstruction would cost billions, and Russia would not pay it. CNN quoted “current and former senior US government officials” as claiming that the Russian Ambassador to the United States is considered a spy by US intelligence. Nepszáva interviewed analyst Attila Juhász of the Political Capital Institute think tank to preview a report on Russian ties with the far right in Hungary.

The Ministry condemned all three stories as fakes (or in CNN’s case, “an egregious media provocation”), arguing that the deputy minister did not say it, the ambassador was not a spy, and Russia was not supporting the far right. It also accused all three outlets of not contacting it.

For each article, it would have been legitimate for the Ministry to deny the claims if they contained factual errors, and to do so publicly: one of the roles of any press service is to set the record straight when inaccurate reports are made.

However, there is a difference between denying an accusation and attacking an article. It is theoretically possible that the sources quoted in each article were wrong; but the only way in which the articles themselves could legitimately be described as “fakes” would be if they had invented the quotes. As long as the quotes were genuine, the outlets were not committing “fake news” in citing them.

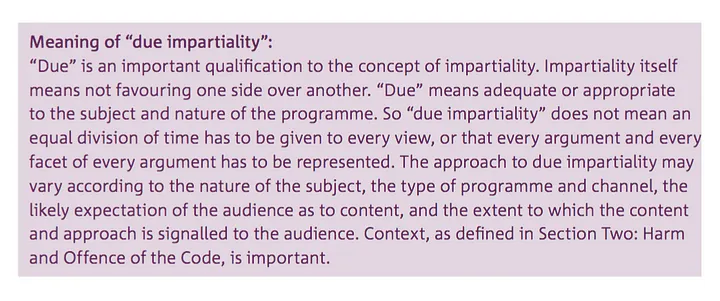

Similarly, they were not committing “fake news” by not contacting the Ministry. Balance is a vital attribute of journalism, but it must be carefully defined. Currently, the most solid legal definition is that used by the UK telecoms regulator, Ofcom, which speaks of “due impartiality”:

Proving failures to provide “due impartiality” is a complex and lengthy process requiring detailed evidence; examples of such proof can be found in Ofcom’s findings that Kremlin broadcaster RT violated the obligation in August 2011, February 2012, July 2012, March 2013, March 2014, July 2014 and March 2016. The March 2016 case alone took almost four months to investigate and ran to 26 pages of argumentation.

To insert a single line claiming that a given outlet “never asked” for a comment, and then label it as fake on that basis, simply highlights the Ministry’s lack of competence in questions of balanced reporting.

Conclusion

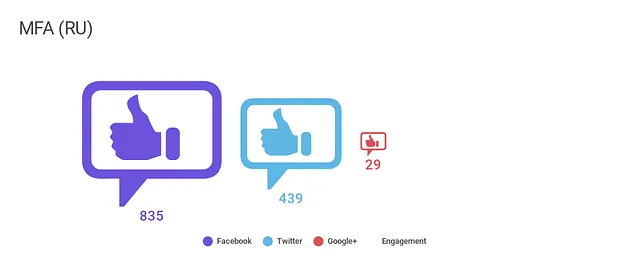

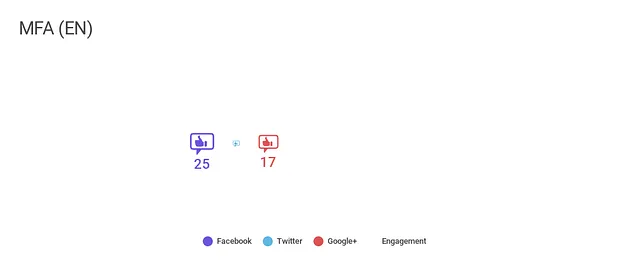

The Ministry’s “fake-busting” page has not been a success. As of March 22, its English-language version had only had a few dozen likes on social media; the Russian-language version had around 1,300.

This is understandable. As an analysis of “fake news,” the Ministry’s page is worthless. Its standards of evidence are non-existent, it misrepresents key facts, and it appears to make no distinction between falsehood, potential inaccuracy, and simple criticism.

Moreover, there is very little indication that the Ministry itself took the effort seriously. As we have seen, the first five entries failed to provide any evidence at all. Of the other accusations, three were based on false claims, the other three on a failure to understand the role of sources and the concept of due impartiality. Not one of the eleven accusations can be considered credible.

Far from being a genuine effort to expose false reporting, or even to correct unfavorable coverage, this appears to be an attempt to confuse readers by hurling accusations of “fake news” at Western outlets, especially those which criticize the Kremlin. As such, it fits firmly into the Kremlin’s template of responding to criticism by dismissing the critics, distorting the facts, distracting from whatever it is accused of by accusing others of the same, and dismaying its opponents.

It is also, potentially, a tool of intimidation and repression. Rather than working with journalists and trying to inform and persuade them — which is the job of a press service — it promotes an antagonistic relationship in which the Ministry acts as both judge and jury on the professionalism of individual journalists. This is not the job of a press service.

Thus the Ministry’s “fake news” page is not a serious endeavor, but it raises serious concerns about the Foreign Ministry’s attitude to reporting, and reporters.