An Unlikely Opposition

How Sputnik Turkiye is posing as opposition media exploiting vulnerabilities in Turkey’s narrowing media space

An Unlikely Opposition

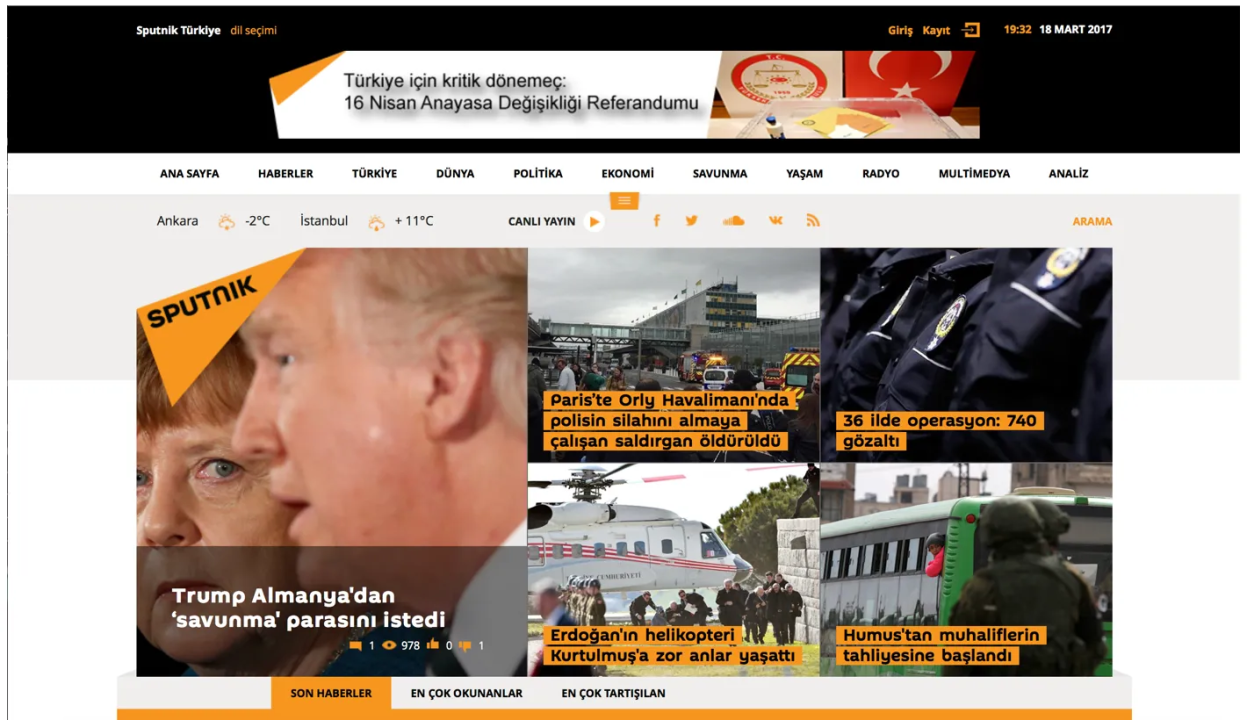

BANNER: Sputnik Turkiye: “Turkey’s Critical Turning Point: The April 16 Constitutional Referendum”

Turkey will hold a referendum on constitutional changes aimed to transform Turkey’s parliamentary system to a presidential system with sweeping executive powers on April 16.

Sputnik is no ordinary media outlet, and Turkey is no ordinary media environment

A successful referendum is Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s top priority. Hence, the referendum has become too hot to touch for many in the media amid an extensive crackdown against the press in Turkey.

The build-up to the vote has also seen intense diplomatic rows, as some European nations block Turkish officials from campaigning on their territory, and Ankara reacts with accusations of Nazism and threats to reevaluate its relationship with Europe.

President Erdogan’s spokesman, Ibrahim Kalin, suggested that the row was a result of European bias and xenophobia, a view which analysts say could help weaken opponents of the referendum, who are currently leading in most polls.

Yet, as President Erdogan’s supporters and referendum backers continue to blast European leaders for blocking their campaign efforts abroad, they are silent about the messaging coming from Sputnik Turkiye, a Kremlin-funded media entity whose official task is to “report the state policy of the Russian Federation abroad.”

This is remarkable when compared with the pressure faced by other journalists in Turkey, and leads to the question of why Sputnik Turkiye is able to report so much more freely than others.

Sputnik Turkiye: reporting heavily on the referendum

Since Turkey’s parliament on January 21 passed the legislative package to amend the constitution, Sputnik Turkiye has produced well over 300 articles on the referendum, at an average rate of 4–5 articles per day.

All articles related to the referendum can be found on Sputnik Turkiye’s subpage devoted to the topic. Sputnik clearly attaches considerable importance to its referendum coverage: a banner linking to it regularly adorns the homepage.

A manual sentiment review of all articles posted on Sputnik’s referendum page from January 20, 2017 to March 9, 2017 showed that a significant majority were pro-“no”. Some 45% slanted towards the “no” camp’s views and issues; 29% slanted towards the “yes” camp and the Turkish government’s position; and 26% did not have a leaning. Each story was reviewed and coded to determine whether it was in favor, against, or neutral on its coverage of the Turkish referendum.

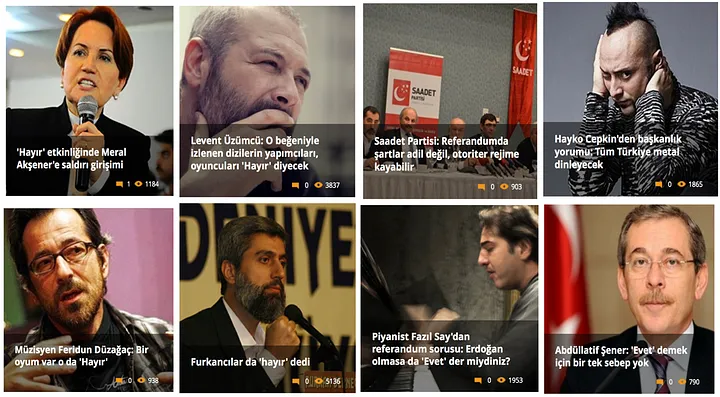

The quality of the coverage also differed significantly. The majority of “yes”-leaning articles quoted Turkish government officials. The “no”-leaning articles, however, drew on far more diverse sources, including political parties, diaspora groups, authors, journalists, actors, and musicians. Sputnik Turkiye also regularly reports on harassment and intimidation against those who support the “no” campaign.

Sputink Turkiye amplifies its content through Turkish-language accounts on Facebook and Twitter. Due to the lack of trust in traditional media sources, Turkey’s public ranks among one of the top populations to consume news through social media. Many of Sputnik’s articles are also shared by other Turkish media sites, often word for word.

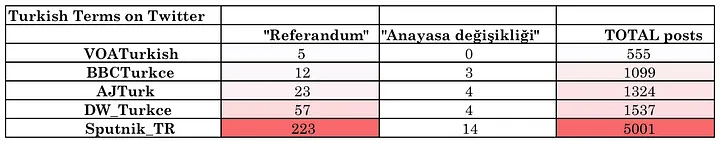

When compared to other international public broadcasters in Turkey, Sputnik Turkiye is by far the most active on social media. The BBC has more Twitter followers, at almost 2.5 million, but Sputnik tweets more regularly and is more focused on the referendum campaign.

According to a machine analysis conducted between February 8, 2017 and March 9, 2017, Sputnik tweeted 223 times about the referendum, over 7 times a day. This was more than double the referendum mentions of Voice of America, BBC, Al Jazeera, and Deutsche Welle, combined.

Sputnik, once banned, is now at the center of Russia-Turkey relations

Turkey has not always allowed Sputnik so much latitude. On April 14, 2016, after months of escalating tensions over Turkey’s shooting down of a Russian warplane, Sputnik Turkiye was banned from Turkey and its bureau chief at the time, Tural Kerimov, had his visa and work permit revoked.

The ban came after months of hostile reporting in Sputnik Turkiye, mirroring the Kremlin’s anti-Turkish narrative. This included comedic portrayals of President Erdogan, claims of Turkey’s support for chemical weapons in Syria, amplification of the PKK’s views, and other topics.

The ban on Sputnik Turkiye was lifted in August 2016 after President Erdogan expressed regret to President Putin for the shooting-down of the Russian warplane and relations were restored. Soon after Sputnik Turkiye came back online, Turkey’s Department of Telecommunications and Communications, which had originally instated the ban, was eliminated as part of a post-coup emergency decree.

Almost immediately, the Turkish government participated in a campaign to repair Sputnik Turkiye’s image. The Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu gave an an exclusive interview to the outlet, explaining Russia’s part in realizing the threat of the Gulenists who were allegedly behind the July 15 coup attempt and other articles appeared indicating close cooperation between Russia and Turkey.

The prominent role Sputnik Turkiye played in the breakdown and subsequent restoration of Russia-Turkey relations illustrates both its role as an amplifier of Kremlin messaging, and the Turkish government’s understanding of that role.

A geopolitical puzzler

Since their rapprochement, Russia and Turkey have held four high-level meetings (most recently on March 10, 2017), eased sanctions, signed joint agreements to cooperate in the areas of energy, defense, tourism, and culture, and declared the intention to complete the controversial Turkstream pipeline project and potentially enter into an agreement to purchase the Russian S-400 air defense system.

Given this public display of cooperation, it is very striking that Sputnik — in other languages an invariable channel for the Kremlin’s messaging — should have taken the “no” side so strongly. This is at odds with Russia’s recent rapprochement with the Erdogan government, and at odds with the government’s stance on reporting. However, it is clear that Sputnik Turkiye is slanting its coverage against the “yes” side, and thus against Erdogan.

One likely motivation for Sputnik’s focus on the Turkish referendum is geopolitical influence. The recent rapprochement between Ankara and Moscow appears to be based on pragmatism rather than conviction, particularly as the war in Syria rages on.

Turkey and Russia do not see eye to eye on many international matters, including the way forward in Syria; Sputnik Turkiye is a useful check on President Erdogan, and its apparent freedom of maneuver appears a reminder of Kremlin dominance.

According to Turkey analyst and author of “The New Sultan: Erdogan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey,” Soner Cagaptay, “Putin has a long-term interest in seeing Erdogan [and his brand of political Islam] fail. Russia’s Muslim community, which constitutes 15–20 percent of that country’s citizenry, is almost completely Sunni Muslim, and Putin sees the rise of (Sunni) political Islam as a domestic threat. Moscow fears that the success of Sunni political Islam in Turkey could embolden and perhaps, even radicalize Russian Muslims.”

For this reason, Cagaptay says “Putin will be less than forgiving of Erdogan’s mistakes and will use opportunities to boost anti-Erdogan opposition.” These hybrid tactics include anti-referendum messaging on Sputnik Turkiye, support to Kurdish militant groups in Syria that threaten Turkey’s domestic security, and the airing of embarrassing email hacks and suspicious cyber exploits.

Clickbait in the guise of an independent voice

Another explanation for Sputnik’s extensive coverage of the referendum may be a desire to draw readers to Kremlin views on other issues. As Turks look for fresh perspectives and alternate sources of information in a tightly-controlled media environment, Sputnik Turkiye draws readers in through its shockingly open coverage on domestic issues.

From there, readers are directed to other stories, including biased, slanted, and, often, outright inaccurate content about NATO, the United States, the conflict in Syria, and the European Union. One false narrative that seems particularly prominent in Sputnik Turkiye’s coverage links the United States, the July 15 coup, and other terrorist attacks in Turkey together and accuses the US for most of Turkey’s woes.

The best defense: a strong, independent media in Turkey

As a NATO Ally on the border with Syria, Turkey plays a key role in some of the most pressing international matters of our day, including the refugee crisis and its impact on Europe, the Syrian conflict, Cyprus, and physical and energy security issues throughout Europe and Eurasia. For this reason, Turkey and Turkish public opinion matter.

The West should consistently raise the dangers posed by Turkey’s narrowing information space and work with international public broadcasters to bolster diverse programming in the absence of a strong, independent media in Turkey. Otherwise, Sputnik Turkiye will continue to dominate Turkey’s information space, aggravate relations between Allies, and impede progress on key areas of common interest within the transatlantic space.