Russian Narratives on NATO’s Deployment

How Russian-language media in Poland and the Baltic States portray NATO’s reinforcements

Russian Narratives on NATO’s Deployment

Share this story

BANNER: Time series of posts on the main negative narratives about the NATO deployment

In July 2016, NATO member states decided to enhance the alliance’s presence in Eastern Europe on a rotational basis, with four multinational battalion-size groups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. The move was intended to strengthen NATO’s deterrence and defense posture and serve as a reminder that “an attack on one is an attack on all,” in line with Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty.

The Kremlin interpreted the decision as a hostile act and pledged to respond. The main element of that response has been an increase in Russian military activity in the Baltic Sea region, in parallel, pro-Kremlin and Russian state-funded media in the region have run a series of negative stories on the deployment. While some of these were legitimate pieces of journalism, some were significantly distorted, and at least one was entirely faked.

The DFRLab has been monitoring coverage of the Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish and Russian since February 4, in an attempt to categorize and classify the main themes. Coverage was classified according to its editorial tone, overall message, and the visual materials accompanying and framing the publication.

The most striking feature of this analysis was that the eFP deployment received significantly more negative coverage in Russian-language media than in the local languages, where coverage tended to be either factual and neutral in tone, or positive towards the deployments.

This post will seek to identify the main negative narratives used, and the extent of their impact.

The negative narratives

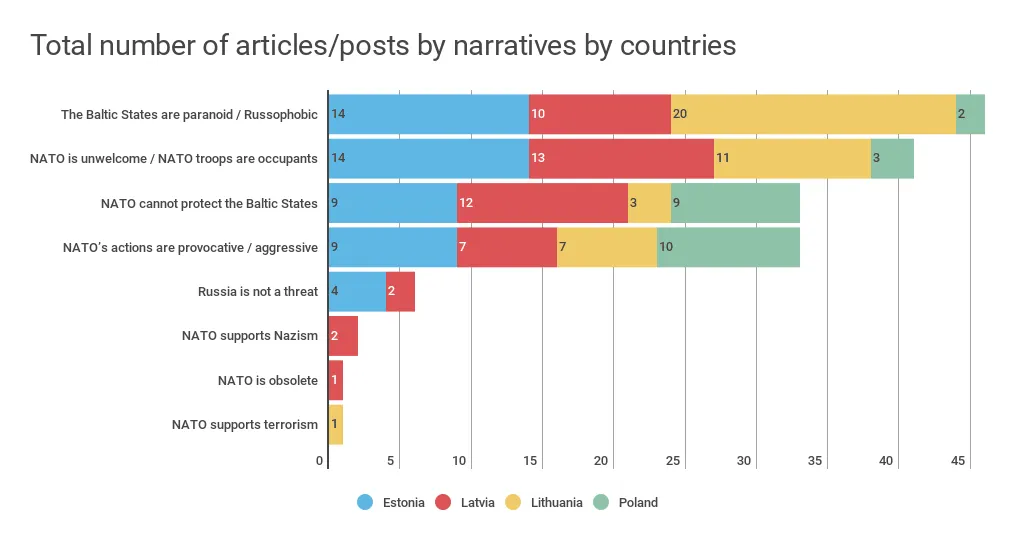

Eight distinctive negative narratives were identified over the monitoring period. In order of prevalence, they are:

1. The Baltic states are paranoid and / or Russophobic;

2. NATO is unwelcome / NATO troops are occupants;

3. NATO cannot protect the Baltic States;

4. NATO’s actions are provocative / aggressive;

5. Russia is not a threat;

6. NATO supports Nazism;

7. NATO is obsolete;

8. NATO supports terrorism.

Of these, the first four were significantly more prevalent than the last four, accounting for over 90 percent of posts. For example, a total of forty-six posts from across the four countries and in all languages covered the narrative that the Baltic States are paranoid; just six, four of them in Estonian or referring primarily to Estonia, argued that Russia is not a threat.

Latvia saw the highest number of hostile articles, with forty-seven; Poland saw the lowest, with twenty-four. The message that the Baltic States are paranoid or Russophobic was particularly prevalent in Lithuania, whose President Dalia Grybauskaitė is an outspoken critic of the Kremlin.

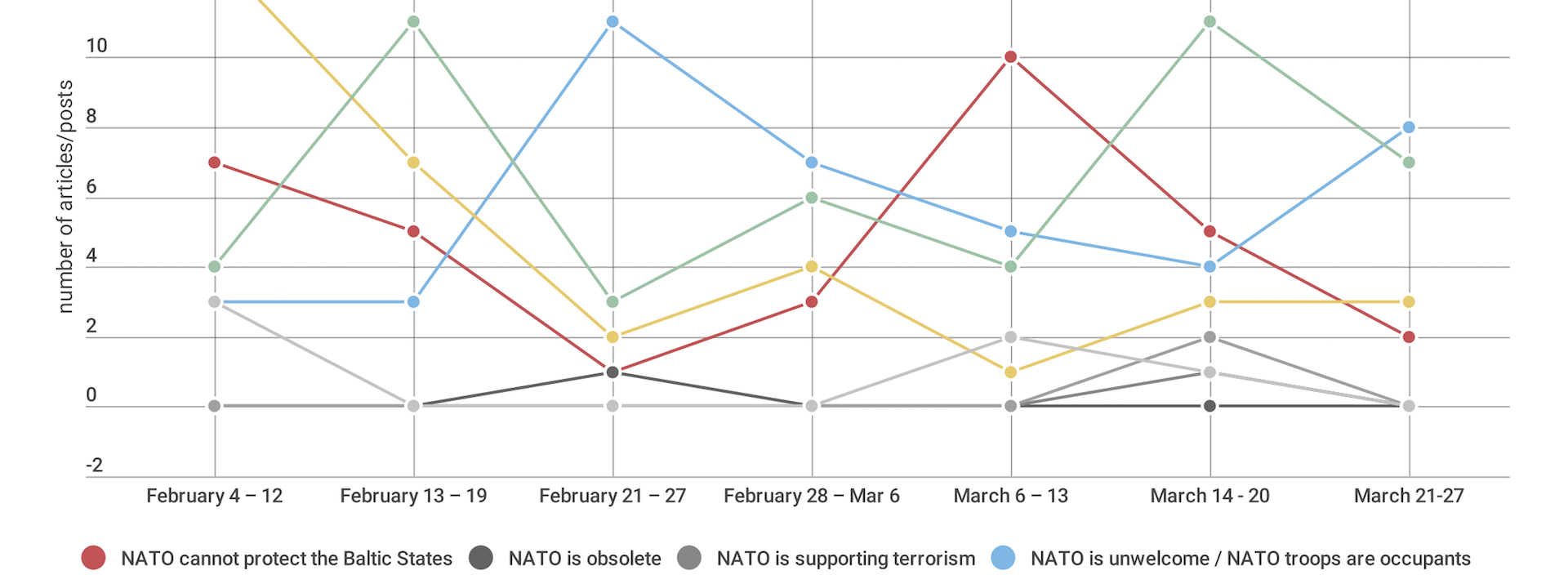

Narratives changing over time

The narratives themselves were not uniform, but developed over time, as the following graphic demonstrates:

At first, the most popular narrative was “NATO’s actions are provocative / aggressive” (yellow line). A recent example of this argument, which carried through into social media, can be seen in a post on VK page “World Politics” (Mirovaya Politika, Мировая Политика) dated March 27.

The post reads:

“Is NATO scratching around Koenigsberg again?

“NATO is circling around Russia’s borders like a black crow. It’s circling and looking for a weak spot, placing military bases, conducting joint military exercises and periodically screaming about alleged Russian aggression and a threat to the West. This comedy has been going on for many years and has become boring. Moscow does not refuse to discuss the disputed issues with the Alliance, but it does not intend to give an account of itself. For Russia to have to give an account of itself isn’t even on the board.

“And after all it itches … NATO can’t get over the Russian “Iskander” missile systems in the Kaliningrad region. Spiegel even decided that Russia will have to explain itself at the upcoming ambassadorial meeting, saying by what right we have become so insolent that we decided to protect our borders from the western threat. You may laugh, but they sincerely believe that this will happen. Moscow was told that it was not worth doing. And NATO’s word is law!”

The post was viewed 9,400 times, shared 20 times, and generated 14 comments, all hostile towards NATO and the West.

The narrative “the Baltic States are paranoid and Russophobic” took over as the most popular topic in the week of February 13–19 (green line). Then it declined, but became trendy again in late March. More articles have covered this theme than any other negative one.

An example of the theme was published by website “Southern Federal” (Yuzhniy Federalniy, Южный Федеральный) on March 15, after a delegation from the NATO Parliamentary Assembly visited Vilnius. Headlined, “‘Putin has already attacked us!’ — Lithuania complains to NATO,” the article described the attitude of Lithuanian members of parliament:

“In the Lithuanian parliament, the NATO people were told that ‘Russia already attacked’ the Baltic republic. Members of parliament described in vivid colors the so-called ‘non-traditional warfare’, in which the opponent (in their words, of course, Russia), conducts ‘hostile actions in the cyber and information spaces, as well as in the field of energy’. (…) It is worth mentioning that Moscow has always denied any of the ‘imperial ambitions’ attributed to Russia by the leadership of the former-Soviet Baltic republics.”

The Yuzhniy Federalniy article was shared almost 150 times on social media, primarily Odnoklassniki. Similar articles were published by Regnum, News Potok, Baltnews.lv, Sv Comercio, and Vesti.lv.

The narrative that “NATO cannot protect the Baltic states” (red line) saw a surge of coverage in the week of March 6–13, after a US-based outlet, the National Interest published a long article on the potential military threat Russia poses to NATO. This, in turn, drew heavily on a study by the RAND corporation published in 2016.

The piece in the National Interest focused on the broad range of Russian military capabilities, and the possible ways in which a NATO-Russia conflict could evolve. One line of the article, summarizing the RAND report, ran, “Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia could be likely Russian targets because all three countries are in close proximity to Russia.” This line was picked up by media in Lithuania and Latvia.

Much of the coverage was directly translated from the National Interest piece. However, a version in pro-Kremlin online outlet Baltnews.lv dramatized and distorted the original, rendering the claim that the Baltic States “could be likely Russian targets” as “will be the first targets.”

The alarmist message was reinforced by a dramatic image of the iconic House of Blackheads in the Old Town of Riga, damaged by explosions and surrounded by rubble. The original medieval building was destroyed in World War Two, giving it added resonance.

The article was shared 489 times on Facebook and just once on VK. This would appear to indicate that it engaged the Russian-speaking population in Latvia, as Facebook is a more popular network in Latvia than VK.

The narrative that “NATO is the occupying force” (blue line) peaked twice, in late February and late March. On the latter occasion, coverage was led by articles claiming that Estonian soldiers will be “evicted” from their barracks to give space to other NATO soldiers.

The RIA Novosti article was based on a report by the Russian service of Sputnik Estonia, which was in turn sourced to an article by the Russian service of the Estonian public broadcaster, ERR. Both these articles reported that some 600 Estonian conscripts would be based in tent accommodation during field exercises, while NATO troops would be housed in their barracks. Neither used the word “evicted” headlined by RIA Novosti; the RIA Novosti article itself did not mention the word anywhere except the headline.

The Sputnik article was viewed 480 times, shared twice and had four likes and one dislike; the ERR version was commented on twice. By contrast, the RIA Novosti version was viewed almost 16,500 times, liked 241 times, shared seventy times and commented fifty-four times. Its use of the word “evicted,” unjustified by anything in the text, seems to have struck a chord.

Hostile, unwelcome… and fake

The narrative that NATO forces are dangerous, violent occupants has also been supported by fake articles, in the narrow sense of stories reporting untruths, apparently deliberately. At least three apparent fakes were exposed during the reporting period, two in Lithuania, one in Latvia.

The first popped up in Lithuanian media in mid-February. It alleged that German soldiers had raped an underage girl in Jonava, Lithuania. The story was planted through an e-mail to the Speaker of the Lithuanian Parliament. Later, a public blog post was created.

The blog suggested that the “news” about the rape had been deliberately suppressed as a “conspiracy against the people,” and printed screenshots from media that had published the fake story. In fact, the story had been exposed as a fake by police, and outlets which had reported it took their articles down.

The blog “auraspress.wordpress.com” seems to have been created just for this post. As of March 31, there were no other posts on the blog.

The title, text widget, contact section and about sections were left with a placeholder text.

The original story was traced to a source from “outside the EU,” according to Deutsche Welle.

Another fake story focused on Latvia. It alleged that NATO soldiers there would be allowed to carry loaded guns, posing a threat to public safety. The story was picked up by at least ten Russian-language channels, among which was Regnum Belarus, which headlined that “NATO soldiers in Latvia will move around with loaded weapons.” Sputnik Radio Latvia also spread the story in an article reproduced by RIA Novosti:

“The local Ministry of Defense has prepared amendments to the law, allowing soldiers to wander around with loaded weapons, saying it’s necessary. All of a sudden the enemy’s there, and you’re in a bar, and your bullets are back on base.”

As with so many false reports, the story had a grain of truth, in that the Latvian authorities had approved a legal amendment allowing NATO forces to cross the border into the country while armed, in an attempt to speed any reinforcement efforts. However, as the Latvian Ministry of Defense clarified, this did not allow them to go around armed.

A third fake was published on March 28, again on a WordPress site. This alleged that a German commander of the eFP battalion in Lithuanian — Christoph Huber — was a Russian agent.

The story used a social media post, allegedly published by Mrs Huber, to corroborate the statement:

Delfi.lt found that the images allegedly depicting Christoph Huber in Moscow were fake. The image of Mr Huber in the Red Square was in fact a Getty Images picture of a French astronaut, Thomas Pesquet, with a photoshopped face.

The story was picked up by anti-NATO groups online. The story was also translated to Russian and published by several media outlets.

Some stories added a negative interpretation to existing reports, such as when British soldiers in Estonia were warned of potential pro-Kremlin provocations in pubs and bars. Pro-Kremlin media represented this warning as a carte blanche for all crimes that the British soldiers may commit during their stay, arguing that these will always be blamed on Russia.

According to the lead paragraph of the Gazeta.ru article:

Soon, additional forces from NATO countries will arrive in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. At the same time, those servicemen of the North Atlantic Alliance who are already in the Baltic countries repeatedly got into scandalous situations. The authorities of the Baltic republics are afraid of new unpleasant incidents and, just in case, are already accusing Russia of them. Residents of the town of Tapa, where the NATO base is located, told Gazeta.ru how the alliance’s soldiers usually behave.

The outlet went on to cite an anonymous source “close to Estonian ruling circles”:

“The fact is that young guys will come to a very calm country, where there are a lot of single women, as the men have moved to work in Finland, Germany and the same England. Alcohol is also cheaper here than in the UK. Clearly, they won’t get away without fights and other excesses involving these soldiers, that’s why they invented in advance an excuse for the terrible Russian women provocateurs.”

Falling on deaf ears?

A number of individual posts achieved significant impact, with thousands of views and dozens or hundreds of shares. However, many other posts achieved little or no impact.

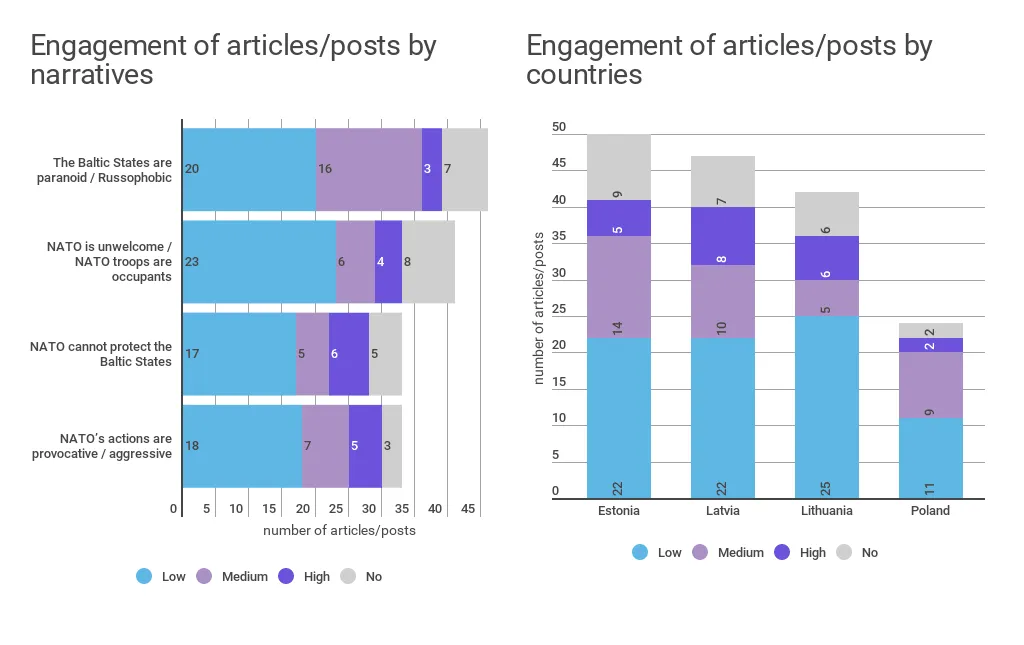

The graphic below visualizes the spread of the different themes. The light blue color represents articles and posts with low engagement; dark blue indicates articles and posts with high engagement.

Overall, the narrative with the highest number of successful posts was that NATO cannot protect the Baltic states, followed by the narrative that NATO is hostile or aggressive. Latvia saw the highest number of successful posts, with eight.

The total number is also noteworthy. Overall, over 150 articles were identified as negative over a period of seven weeks, at a rate of roughly three a day. This represents a significant reporting effort.

Conclusion

The eFP deployment to the Baltic States and Poland has been met with a significant flow of hostile commentary and reporting. While the majority of the hostile articles and social media posts detected generated low engagement, some had considerable reach.

Four narratives, in particular, were the most prevalent, accounting for the great majority (around 90 percent) of articles. These were that the Baltic States are paranoid or Russophobic; that NATO is unwelcome; that NATO cannot protect the Baltic States; and that NATO is the aggressor.

Such articles reinforce long-held Kremlin narratives that the Baltic States are intrinsically anti-Russian, that NATO is the aggressor, and that the accession of the Baltic States and Poland to NATO was a destabilizing action which ran against their own best interests. As such, they fit firmly in the context of the Russian government’s broader information campaigns.