BANNER: Screen capture of footage of a demonstration in Kyiv against the May 16 decree banning a number of Russian sites, including social networks Vkontakte and Odnoklassniki (source)

On May 16, Ukrainian President Poroshenko signed a decree that set a ban in motion for a number of Russian sites and services, including the social networks Vkontakte (VK) and Odnoklassniki (OK), Mail.ru, and the massively popular Yandex, a Russian analogue of Google. These sites are extremely popular in Ukraine, with usage rates similar to that of Facebook and Google in the United States.

For an idea of just how popular these sites are, Hromadske cited analytics company Gemius stating that Ukraine has 10.8 million users on Yandex, and that 78% of Ukrainians who use the internet had an account on the social network Vkontakte. For comparison, Pew Research claimed in 2016 that 79% of online Americans used Facebook.

Poroshenko’s move drew both fierce praise and criticism, with some saying that the ban was long overdue given Russian control over these networks, and others claiming that there has been an “Erdoganization of Poroshenko” through these censorship measures. But an under-analyzed aspect of this ban is the effect on Ukrainians in the Donbas, both in government-controlled and occupied territory — how will this ban affect these populations, who rely on the now-banned social networks to reach loved ones and access vital, perhaps even life-saving, information?

Uses of social networks in the Donbas

At @DFRLab, we have frequently highlighted how civilians who live near the front lines of the war in eastern Ukraine have used social networks. Many of the noteworthy examples of the use of the social network VK will be highlighted here, showing the wide range of uses the website has to help civilians cope with and survive the war. We will also note potential alternatives that are currently being used to the services provided by VK since this ban was announced, or where there are potential growth areas.

Checkpoints and border control

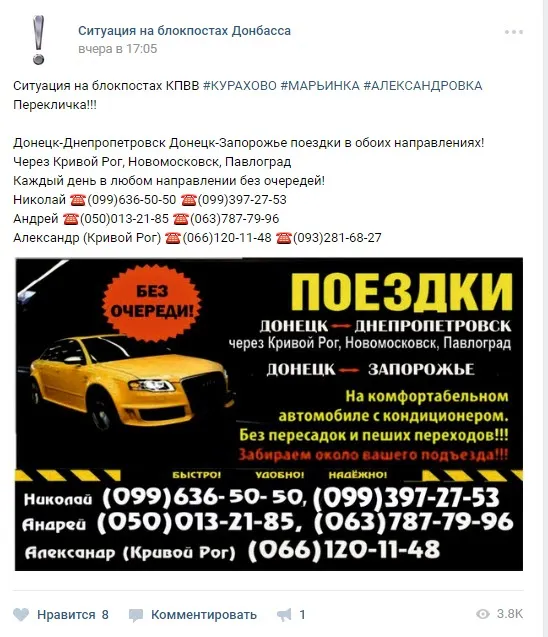

The lengthy queues at the checkpoints between government-controlled and occupied territories is one of the most pressing issues for civilians near the front lines. In the DFRLab investigation “Deadly Congestion at Ukrainian Checkpoints,” we highlighted how social networks assisted civilians in dealing with these queues. For example, the VK group “Situation at Donbas Checkpoints” provides information on delays and closures at checkpoints, along with advertisements of shuttle services to help civilians safely cross checkpoints.

While this VK group and similar communities on social networks provide frequent and timely information to their subscribers, there are similar services provided in regional and national newspapers. At the very least, this VK group also operates a normal website separate from the very popular social network group. Additionally, the website Reporter.dn.ua provides daily updates on the status of each checkpoint. Other news websites print similar information, such as Donpress. Furthermore, services on non-blocked social networks provide updates on checkpoints, such as the Donbass SOS Facebook page, which publishes some of the most detailed reports on the daily volume of traffic and congestion at checkpoints.

Humanitarian assistance

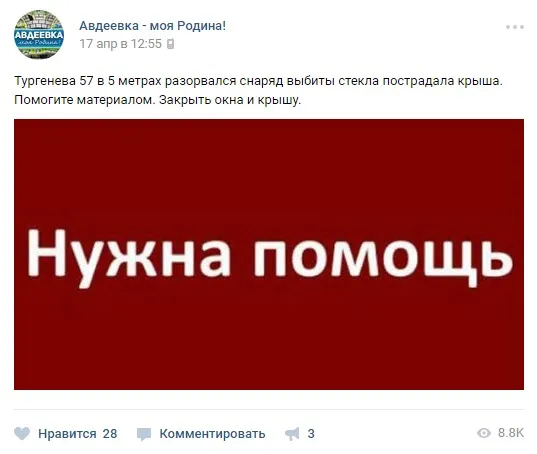

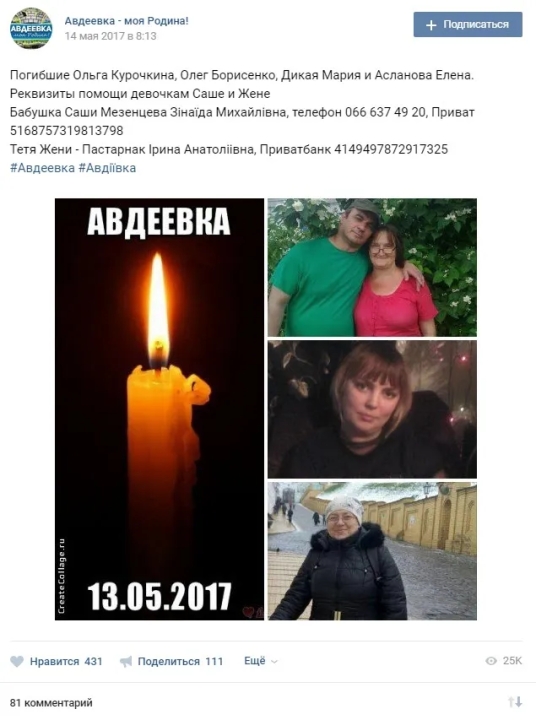

With daily reports of shelling and violence across the Donbas we also see frequent humanitarian efforts organized through social networks to assist those affected by the war. The VK group “Avdiivka — My Homeland” is one of the best examples of this, as users and administrators in the group use the social network to organize efforts to repair houses, raise money for victims of the war and their relatives, and distribute humanitarian aid.

While VK has a tremendous reach for gathering humanitarian assistance — remember that over 75% of internet-using Ukrainians have an account on the site — there are other ways to gather this support. The group “Avdiivka — My Homeland!” (which posted the two previous examples) is migrating to Facebook, as it has announced nearly every day on its VK page since the announcement of the decree.

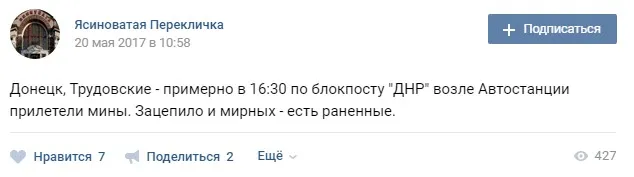

Information regarding fighting

Perhaps most importantly, VK is used heavily by civilians in sharing and receiving information regarding ongoing fighting in the area, with minute-by-minute reports of incoming and outgoing fire. Much of this information is gathered through dedicated groups or nightly threads, often called “Pereklichka” (or “roll-call”) where locals share information about on-going fighting and its effects. For example, the “Yasynuvataya Pereklichka” VK group publishes information received from locals each day:

While VK is the most active website to share this information, we can also find the same timely reports on non-banned social networks, such as Twitter and Facebook. Many individuals on Twitter gather witness accounts from across social networks and share them on their own account, with accompanying time-stamps and locations.

ФБ 18.03 К Пескам и назад мотается строительная техника. Краны, экскаваторы.

— Hochu dodomu v UA (@hochu_dodomu) May 23, 2017

What’s next?

Clearly, VK and other sites banned by the Ukrainian presidential decree are vital to the lives of civilians still living in the Donbas, both for the reasons listed above and so that they can easily communicate with friends and family back home.

The DFRLab spoke with a person living in occupied territory in the Donetsk Oblast, asking what they thought residents of the Donbas would do after the ban, considering how Russian-language social networks are especially popular in eastern Ukraine win comparison to the rest of the country.

They said that there are already internet bans in place in occupied territory, after orders from the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, and described these new bans as mostly likely affecting those using their mobile phones with Ukrainian providers. But in government-controlled territory, the person we spoke to said that they “do not agree with any ban” censoring information online, but thought that it could be useful for the war effort, as it may prevent Ukrainian soldiers from oversharing information from the front lines.

Furthermore, our source told us that they think that many Ukrainians will adapt to the ban either by moving to non-Russian social networks — especially Facebook — or by using methods to get around the bans, such as VPNs. However, older people who are not as tech savvy and less familiar with Facebook and Twitter may stop using social networks altogether and have to find new sources for information — or have their more tech literate friends or relatives show them how to get around the bans implemented by the new decree.

Whether or not Ukrainians do move en masse to Facebook, it is clear that Ukraine is pushing them in that direction, along with (to a lesser degree) Instagram and Twitter. For example, Ukrainian politician Yulia Timoshenko and her political party have urged Ukrainians to migrate to Facebook.

Similarly, President Petro Poroshenko’s VK page — which, despite the ban, is still online with nearly half a million followers — urges Ukrainians to follow him on Western social networks, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Overall, the success of this ban and the amount of censorship and hardship it imposes on its citizens will be determined by how many Ukrainians migrate to other social networks. There has been an early surge of Ukrainians moving towards Facebook, as seen in the creation and increase of membership in Ukrainian Facebook pages and groups, but the number of participants is still dwarfed by their VK counterparts. For example, the previously discussed Avdiivka group has still not topped 1,000 likes or 3,000 followers on Facebook, but has over 37,000 participants on VK.

If this gap does not narrow in 2017, then it could be a sign of a stifling of online discourse in the Donbas, a failure of the decree due to greater use of VPNs, or a migration to alternative social applications that are more friendly to mobile users, such as Viber/WhatsApp groups or Zello (walkie-talkie) networks.