Russian Pop Goes Political

And YouTube users are unimpressed

Russian Pop Goes Political

Share this story

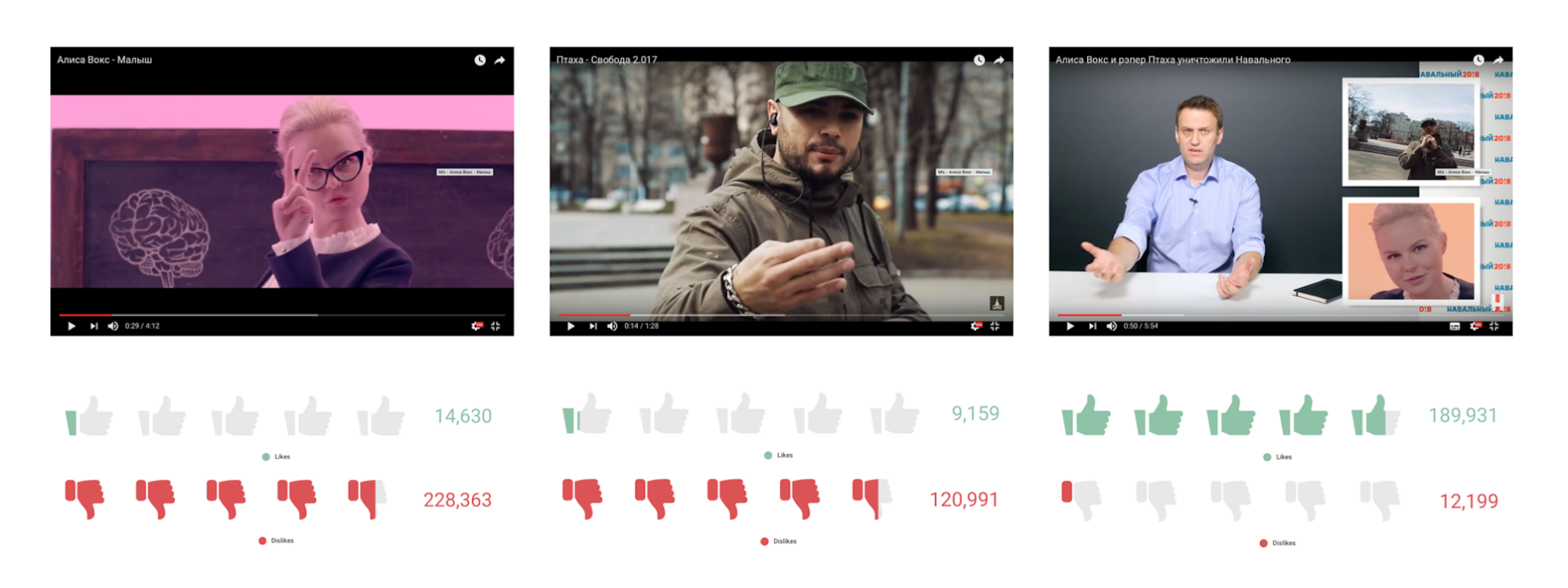

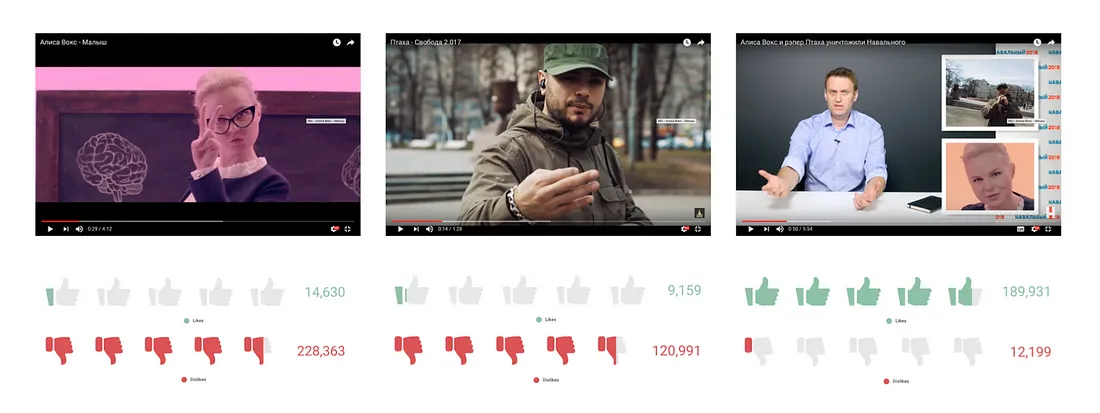

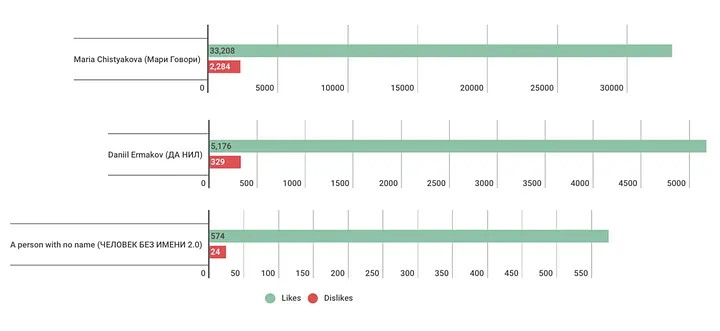

BANNER: Comparison of likes and dislikes of three YouTube videos around the anti-corruption protests in Russia.

On May 15, Russian pop singer, Alisa Vox (Алиса Вокс), who recently started her solo career after quitting a popular band “Leningrad” known for their satirical songs, released a new single called “Baby”(Малыш). In the song, Vox criticized youngsters who went to anti-corruption protests, claiming they lack understanding of history or grammar and politics.

The song starts with the lyrics:

“On a beautiful sunny day he is going to a protest. He takes his banner with weak hands. There are four mistakes in two words on the poster. But his heart is beating in passion and eyes are full of rage.”

It continues:

“It’s never too late to learn from mistakes. If your heart wants changes, start with yourself.”

The song concludes:

“Freedom, money, girls — everything will come, even power. Don’t get into politics, baby, go and get yourself familiar with the issue first.”

The last word in the lyrics (матчасть) in Russian language sounds very similar to the word молчать, which means “keep quiet” and also caused some controversy.

In a week she raised over 2 million views. However, much of the Russian audience on YouTube wasn’t impressed by her message. As of May 26, the song had received over 230,000 dislikes and under 15,000 likes.

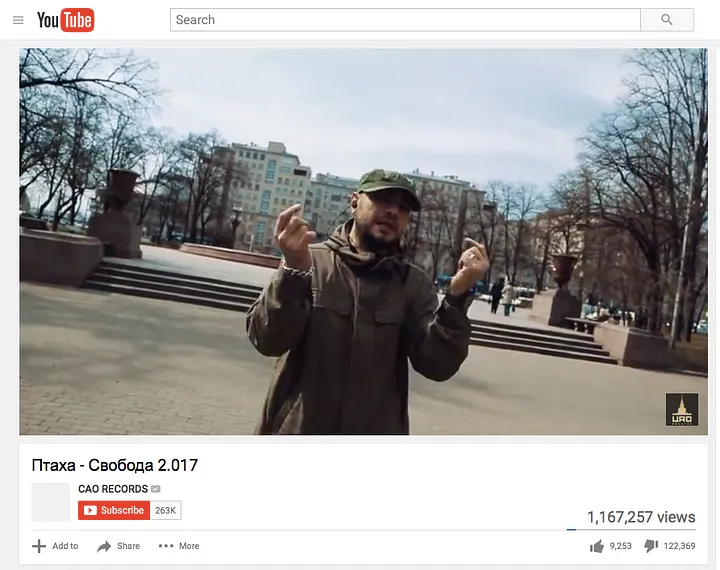

This not the first time that a Russian musician has accused youngsters of going to protest without much understanding. A month after anti-corruption protests across Russia on March 26, Russian rapper Ptaha (Птаха) released a single called “Freedom 2.017” (Свобода 2.017) in which he called people who went to the protests “posers:”

“Democratic rebellion, the freedom 2.017. Posers are sitting on lamp-posts — the hope of the nation. RF, MSK from Tula city Ptaha, the CENTER. Hello to all adequate people and have a nice summer.”

This video also seemed to strike the wrong chord with the online audience, gaining over 122,000 dislikes and only just over 9,000 likes.

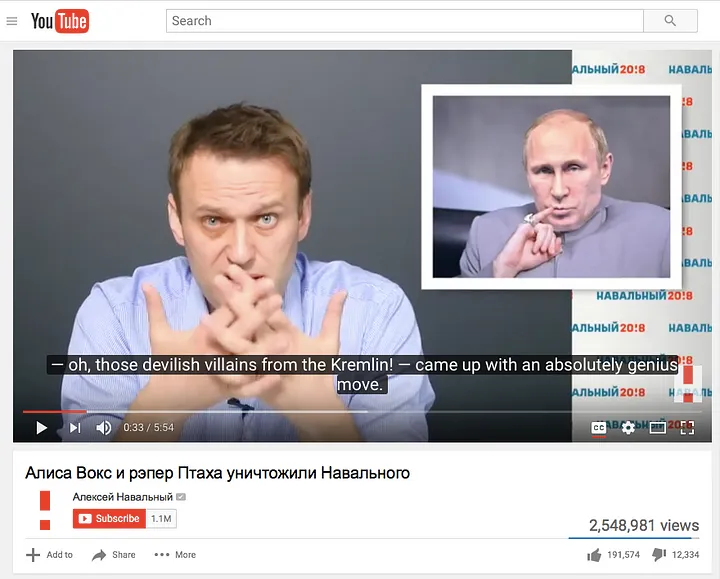

A day later after Vox’s “Baby” was released, anti-corruption campaigner and opposition leader Aleksey Navalny, who organized the protests in Russia on March 26, published a video in which he ironically admitted that the two singers had defeated him, against a backdrop including a meme of Russian President Vladimir Putin as Dr. Evil.

“It’s all gone,” cries Navalny, “It’s all gone. All this doesn’t have any sense.”

“Alexey, please, you need to record one more video,” a voice behind the camera begs.

“Come on, what new video, what for?” Navalny asks. “Don’t you understand what’s going on? Everything is pointless. It’s all pointless now. We have lost the student audience forever. Now no one ever will listen to our words again. Now for sure no one will come to the anti-corruption rallies, because the Kremlin, oh, those devilish villains from the Kremlin, they came up with an absolutely genius move.”

Unlike the counter-protest videos, Navalny’s video response raised almost 2.5 million views, over 190,000 likes and only 12,000 dislikes.

Below is the comparison of how many likes and dislikes each video raised as of May 24:

Response from YouTubers

Soon, other video bloggers began to respond to Vox’s song. A day later the video blogger called Человек без имени (“A person with no name”) commented on the propaganda effect of the Vox and Ptaha videos:

“So, if we talk about the fact that people will stop going to your concerts and buying music, your income, respected propaganda artists, will stop, and there will be no money to live on.”

The same opinion was shared by another video blogger, Daniil Ermakov:

“Today I will talk about two pieces of news in music, which are very connected with politics. The Kremlin bought the rooster Ptaha, and using the change, the Kremlin bought a singer named Vox, I believe, — the former singer of Leningrad.”

On May 17 a parody video clip about the song was released by video blogger Maria Chistyakova. In the video, the blogger accused Alisa Vox of being corrupt and concluded:

“Don’t go Alisa into politics, and everything will be fine”.

The impact of these clips varied widely, from 9,000 views for the nameless blogger to 410,000 for Maria Chistyakova. In all, however, the number of likes was an order of magnitude greater than the number of dislikes.

The musicians respond

The musicians denied the accusations leveled at them. On the same day as Navalny released his video comment, rapper Ptaha released a video answer in which he called Navalny a “blood sucker” and claimed that accusations of him being corrupted are not supported by any evidence.

Alisa Vox gave interviews to both Russian channel RBK and Russian-language Estonian public broadcaster ETV+, insisting that the views expressed in the song are her own, and that she tries to stay out of politics, but she cannot ignore the fact that the young generation in Russia is putting itself in danger at the protests.

In the interview to RBK she said:

“I usually try to keep away from political themes as far as I can, because, as I have already said in many interviews, everyone has to mind his own business — a singer has to sing, a politician has to do politics. But with experience I understood that it’s impossible to live in a society and be independent from it. If there is a burning question that needs to be concluded, in my creative work, I would rather speak up about the topic. I’m personally worried about those who are being cheated and mislead. It’s at least a live danger to climb up lamp-posts. You can just fall down.”

State propaganda, the musical?

Both musicians insisted they had worked independently, despite allegations from Russian outlet Meduza claiming that Nikita Ivanov, a former official of the Russian presidential administration, ordered the song and music video. However, their message was also reflected by the Kremlin-controlled media in its (limited) coverage of the anti-corruption protests.

The mainstream Russian media covered the nation-wide protests very little. There was, at the time, no mention of the protests neither on Dmitry Kiselov’s show “Vesti Nedeli” nor on “Voskresnoe vremya” weekly show, the two flagship current-events programs in the country.

Those state-controlled media which did cover the protests portrayed the young people who went on the streets as victims who had been manipulated.

An explanation on the protests was shared by Russian political scientist Sergey Miheev during a broadcast of the “Evening with Vladimir Solovyev” talk show on March 28.

“The battle with corruption is a new fashionable way to hate the country. The problem is that they (people) don’t assess what is the cookie, but they are told that the cookie is that, that and that. The question is about a sub-culture that is getting out of control not only in Russia, but in other countries as well. The Death Squads. To call teenagers to unsanctioned protests where someone can break their skull is also a kind of a death squad.”

On March 29 in a Pervaya Studiya talk show aired on Kremlin-controlled TV channel Perviy Kanal, it was also concluded that the young people who participated in the anti-corruption protests were manipulated and placed in danger by Navalny. According to moderator Artyom Sheynin:

“There is an editor in my newsroom. She has a 15-year-old son, who also wanted to go to the protest. She told him, don’t do that because it’s not sanctioned, because that, because that, and that and that. She said it as any decent mother would. And he, as a regular teenager said, mum, you don’t understand, you don’t know. Do you know, what question she asked to stop him? She stopped him with a question — son, can you explain why Navalny didn’t take to the protest his own 16-year-old daughter?”

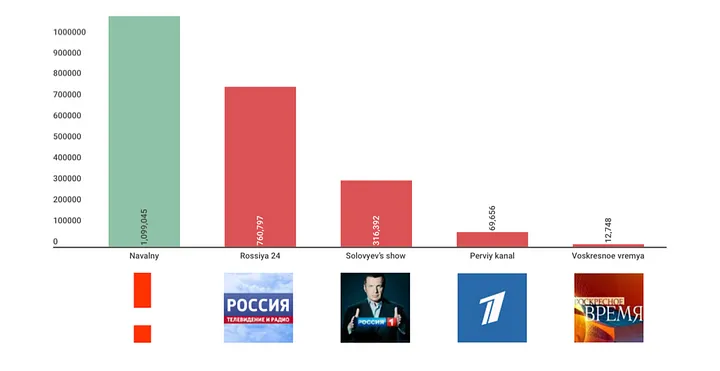

If we compare the impact both broadcasts made on YouTube, it is clear that they do not come close to that of Navalny’s.

Navalny’s YouTube channel has 1,099,045 subscribers, while Vladimir Solovyev’s show has 316,392 subscribers and Perviy kanal news has just 69,656 subscribers. Other broadcasters ignored the anti-corruption protests, such as Kiselov’s show on the Rossiya 24 YouTube channel, which has 760,797 subscribers.

The views the broadcasts raised online were also significantly smaller. While Navalny’s video was viewed 2,508,131 times, Solovyev’s video reflecting on the protests was viewed 339,221 times and the video of the Pervaya studiya was viewed just 41,946 times.

YouTube penetration is, of course, only one measure of reach, and the mainstream TV stations still dominate the Russian information space. The figures do show, however, that on YouTube, at least, pro-Kremlin messages are struggling to come close to the impact which Navalny has achieved.

Conclusion

This is not the first time that pop has played a propaganda role in Russia. In 2008 a pop singer, Natali, sang on TV show “Superstar 2008.” Komanda mechti” called “A man like Putin” (Такого, как Путин). The TV show was a competition between Soviet and Russian pop singers, therefore targeted at conventional TV audience.

Ten years later, pop has again taken on a political role, amplifying a Kremlin message to a new audience. Given the close correlation of their messaging with that of the state, the two singers can be viewed as fitting into the mainstream government narrative, though their reasons for doing so are not clear. In that sense, their songs can be considered an extension of a broader government messaging campaign, but not an effective one.

The video response by Aleksey Navalny was viewed and liked much more than both songs. By all metrics, Navalny won the song contest. Nevertheless, the true effectiveness of state propaganda against the anti-corruption protests will be reflected by the next protests on June 12.