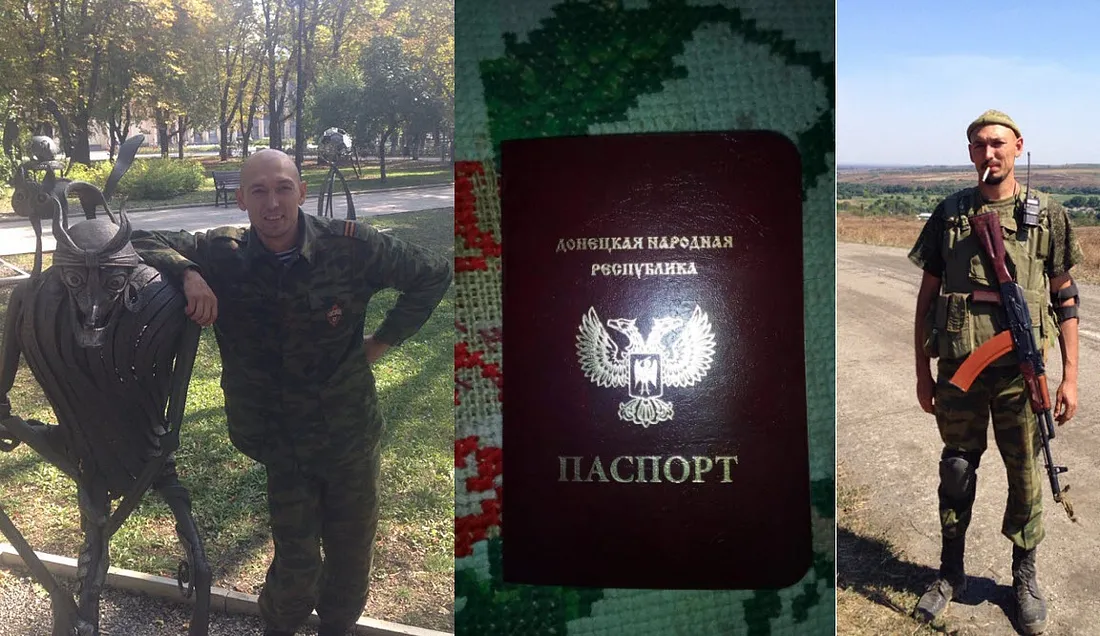

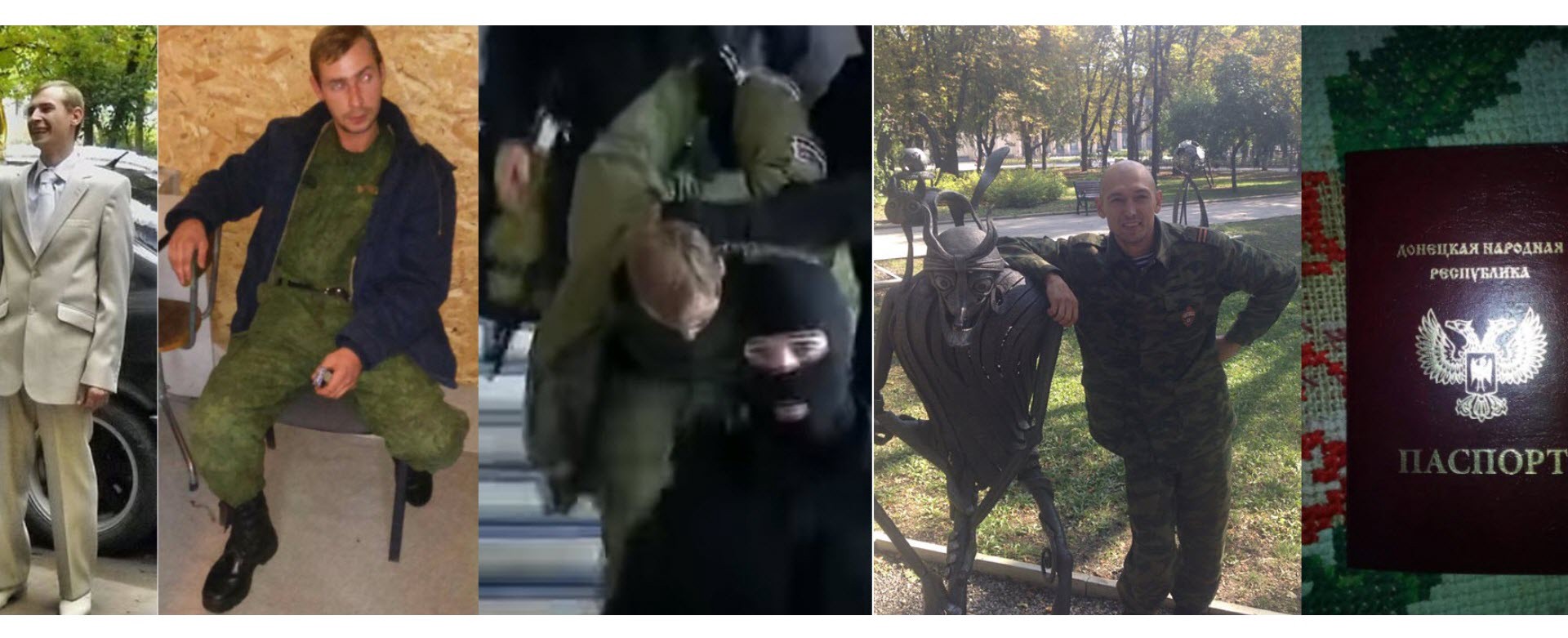

BANNER: Dmitry Oblontsev in Moldova (left), in the Donbas (left-middle), and being arrested at the Chisinau Airport (middle). Ruslan Pastuh in the Donbas (right-middle) and his DNR passport (right)

On Tuesday, June 13, Reuters reported five Russian diplomats were expelled from Moldova in May because they were allegedly recruiting fighters to join the Russian-led separatist forces in eastern Ukraine. Russian officials denied the allegations, but there are some details in the report that can be independently corroborated. What can digital forensics tell us about foreign fighters in the Donbas who hail from Moldova, and can the Reuters report be verified in part or in whole?

Fertile ground for recruitment

Russia’s alleged recruitment of fighters in Moldova is no accident, as the country is one of the best sources for potential recruits. The most obvious reason for this is the breakaway region of Transnistria, bordering the southwestern border of Ukraine and where Russia bases around a thousand soldiers. A number of Ukrainian and Russian foreign fighters participated in the Transnistria War in the early 90s, with allegations that Russia “encouraged or even directly facilitated the inflow of foreign fighters.” This pipeline apparently flows in the other direction as well, with the recent reports of Russia recruiting fighters from Moldova (including Transnistria) to travel eastwards to join the ranks of Russian-led separatist forces in the Donbas.

Moldovan foreign fighters

We know that a large percentage — perhaps a majority — of fighters in the Russian-led separatist forces are Russian, many of which are volunteers. In August 2015, separatist official Aleksandr Borodai estimated that between 30,000 and 50,000 Russian volunteers were either active fighters in or previously participated in the Ukrainian conflict, citing numbers from the Union of Donbass Volunteers. For reference, Ukraine’s Defense Minister estimated that the Russian-led separatist forces had around 40,000 active soldiers in 2015. In February 2016, the Ukrainian Security Services (SBU) estimated that at least 40 Moldovans (the majority of which are from Transnistria) were fighting in the Donbas — a relatively scant number, compared with the number of Russian fighters. Regardless, these foreign fighters deserve treatment due to their background and the recent diplomatic incident.

A new article from Stanislav Secrieru is perhaps the most complete treatment of Moldovan foreign fighters in the Donbas, providing comprehensive data from open sources on the number of Moldovans fighting in the ranks of Russian-led separatist forces. Secrieru details how Russia has not only targeted Moldovans in Transnistria, but also throughout the rest of Moldova and Russia:

“Russian recruiters targeted Moldova’s citizens living and working in Russia (some would make their way to Donbas via the permeable Russian-Ukrainian border in East) and those residing on Moldova’s territory controlled by the central authorities in Chisinau. A mix of economic incentives often wrapped in an ideological package was used to attract those who recently returned from Russia and were looking for sources of revenue. Social networks have also served as an important communication bridge convincing targets to join the ranks of foreign fighters.”

These recruiting methods, combined with Moldovans who decided to fight in the Donbas on their own, have led to dozens of fighters in the forces of the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. Secrieru identified six Russian-separatist military units where Moldovan foot soldiers have been active: the Rusich and Bryanka SSSR battalions in the Luhansk region, and the Volchia Sotnia, Sparta, Vostok, and Somali battalions in the Donetsk region.

We can find many of these fighters on two Russian-language social networks popular in both Moldova and Ukraine: Vkontakte (VK) and Odnoklassniki (OK). The controversial Ukrainian site Myrotvorets (“Peacemaker”) and the Moldovan news site Deschide.md have cataloged much of this evidence over the past three years; additionally, much can still be found on active social network profiles.

A particularly representative example of a Moldovan volunteer can be found in Yury Kudinov, a veteran of the Moldovan army who fought in the Donbas in 2015. He was arrested at the Chisinau airport on November 13, 2015, after returning from Ukraine.

Dmitry Oblontsev was another detained fighter, arrested returning home at the Chisinau airport on November 4, 2015.

Oblontsev is a native of Bender, Moldova, which is technically within the borders of Moldova, but remains under de facto control of the breakaway Transnistrian republic. He fought with the Bryanka SSSR military unit in the Luhansk region, as shown in a photograph of his military identification.

While being arrested at the airport, we can see a Novorossiya patch on his left arm.

Bender, Moldova is a hot-spot for recruits to the Donbas, as seen in the case of a Moldovan man named Andrey Suslov, who fought in the Sparta Battalion in the Donetsk region. This Bender native was reportedly arrested in December 2016 by Moldovan authorities after returning home.

Clearly, returning back to Moldova is dangerous for foreign fighters, as authorities are tracking their citizens fighting abroad. Thus, many Moldovan foreign fighters who have not been arrested now live in Russia or remain in occupied territories of Ukraine, where they do not face the same legal challenges. Ruslan Pastuh, a native of the western Molodvan town Ungheni, fought in the Donetsk area under the name “TsSKA,” in reference to the Moscow sports club. Rather than returning to Moldova, he received a passport from the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic, and according to the latest open source information, still resides in the Donbas.

Corroborating the Reuters report

The recent report is relatively low on specific details, but we can additional context to what is provided. Sources told Reuters that Russian officials “were recruiting fighters from Gagauzia,” a southern and predominantly pro-Russia region of Moldova. While the specific details of this recruitment cannot be confirmed or refuted using open source methods, there is a pre-established pattern of behavior in Gagauzia. In Secrieru’s previously cited article — which was written and published well before the Reuters report — he describes Russia’s 2014 recruitment of young men from Gagauzia:

As protests in Kyiv were getting more violent and Moldova neared signing the Association Agreement with the EU, Russia began recruiting and training on its territory (bases in the suburbs of Moscow and Rostov) young men from the Gagauz autonomy. Overall, about 100 fighters were scheduled to be trained in military diversion tactics and sent back to Moldova to orchestrate public disorder [24]. The plan was foiled by Moldova’s security institutions, which arrested the first group of would-be fighters and dismantled the recruitment network (its members fled to Russia). As several foreign fighters from Moldova that fought in Donbas found temporary shelter in Russia, it cannot be ruled out that at some point Russia may try to re-insert them under false documents in Moldova via Transnistria.

Additionally, a young man from Gagauzia was arrested in Chisinau in October 2014 before he was able to reach Luhansk, where he intended to join up with Russian-led separatist forces.

Moldovan sources also told Reuters that the fighters recruited from Gagauzia were sent to a training camp in the Rostov Oblast of southern Russia. While the exact camp was not specified, it is extremely likely that this camp was the infamous Kuzminsky firing range, which we at DFR Lab have previously written about. Additionally, the Secrieru article mentions that Russia planned on recruiting and training young men from Gagauzia — it is quite likely that this tactic was used to train fighters to be sent to the Donbas, rather than back to Moldova.

Conclusion

Specific details from the explosive Reuters report are difficult to verify, but there is a clear pattern of behavior that we can observe over the past three years. This pattern lends credibility to the allegations from Moldovan intelligence sources, as seen in open source information and the recent research from policy analyst Stanislav Secrieru. Going forward, it is worth paying close attention to future detentions of returning foreign fighters by the Moldovan authorities, as there could be additional evidence of Russian recruiting of these men.

Follow the latest Minsk II Violations via the @DFRLab’s #MinskMonitor.

For more in-depth analysis from our regional experts follow the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. Or subscribe to UkraineAlert.