#ElectionWatch: American Bots in South Africa

Fake accounts boost attacks as ANC picks newleader

#ElectionWatch: American Bots in South Africa

Fake accounts boost attacks as ANC picks new leader

As the African National Congress prepared to choose its new leader on December 18, a cluster of apparently American Twitter accounts began boosting partisan messaging.

The accounts were automated “bots”, created to impersonate genuine Twitter users, and posting at sufficiently low rates to avoid automated detection. They numbered in the low hundreds.

They were not engaged in large enough numbers to swing the political decision; nor do they appear to have fundamentally reshaped the online conversation. However, their presence serves as a warning of, and primer for, likely future tactics, as South Africa heads towards presidential elections in 2019.

As with other elections across the world, South Africans can expect social media to be a propaganda and misinformation battleground, and the bot activity around the ANC’s December National Electoral Conference is a taste of what can be expected in 2018 and 2019.

The ANC contest

The ANC leadership contest was essentially a two-horse race between South Africa’s Vice-President Cyril Ramaphosa, and Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, former chair of the African Union Commission.

The crude figuration of the contest was that a victory for Dlamini-Zuma would have been a victory for sitting SA President Jacob Zuma (her ex-husband) and his supporters in government — some of whom stand accused of large-scale corruption.

Conversely, a victory for Ramaphosa was seen as an attempt by the ANC to self-right its course and placate disgruntled supporters, whose disdain was evidenced by the ANC’s poor results in the last municipal elections.

The two-horse race devolved into horse-trading, with Ramaphosa winning the leadership battle on December 18, but the Zuma faction filling three of the six top ANC positions available. These three have been accused of being in place to fight a rearguard action to protect Zuma from corruption charges and potential retribution.

They include, in the graphic characterization of writer Richard Poplak, “Mpumalanga Premier and gangster supreme David Mabuza,” and Ace Magashule, “a politician so fundamentally unsuitable that he’d be a caricature in a 1930s Hollywood gangster flick”.

And in fact, the #ANC54 conference, as it’s known, is still not quite finalized: 68 delegates whose votes were excluded have mounted a legal challenge to be reinstated.

Ahead of the leadership vote, there were concerns that Twitter traffic could face large-scale manipulation from automated “bot” accounts — accounts which have recently played a significant role in South African politics.

In 2017, a large leak of emails (known as the #GuptaLeaks) produced evidence that an expatriate family, the Guptas, had effectively achieved control of parts of the South African government, including Zuma, using a combination of political chicanery, patronage and outright bribery. They deny all the claims.

The response, with the help of now-disgraced PR agency Bell Pottinger, included the first large-scale fake news propaganda campaign in South Africa, described by the opposition Democratic Alliance as a “hateful and divisive campaign to divide South Africa along the lines of race”.

The African Network of Centres for Investigative Reporting estimated that “the network of fake news produced at least 220,000 tweets and hundreds of Facebook posts to confuse the public between July 2016 and July 2017”.

Twitter traffic: organic flows

To analyze the Twitter traffic for possible irregularities, we conducted machine scans of traffic on the two leaders’ main hashtags: #CR17 for Ramaphosa and #NDZ for Dlamini-Zuma. Each scan ran from 00:01 UTC on December 1 to 18:00 UTC on December 12.

Overall, the scans showed a largely organic pattern of activity. There was significantly more traffic on Dlamini-Zuma’s hashtag: it was used 25,165 times, compared with 13,111 uses of Ramaphosa’s. In both cases, the traffic included both supportive and hostile messaging, indicative of two sets of supporters trying to push their own message and disrupt their rival’s.

The ebb and flow of traffic on the two hashtags was very similar, and followed the news cycle in South Africa, with the highest peak for mentions of both hashtags coming on December 4, when the ANC branch in the province of KwaZulu-Natal held its own primary.

The spike in activity on December 4 is reminiscent of bot-driven activity; however, we conducted a detailed scan of the day’s traffic, and found that the traffic appeared organic, and driven by the news cycle.

The overall traffic numbers also support this analysis. We use three main indicators to assess whether a hashtag has been subjected to artificial inflation: the average number of tweets per user, the proportion of tweets generated by the fifty most active accounts, and the percentage of traffic made up of retweets as opposed to original posts.

The indicators on both hashtags were low. For #CR17, the top-fifty accounts seemed slightly more active than is consistent with purely organic content, generating 13 percent of posts (we would expect a ratio of up to 10 percent, although usually over a larger total number of tweets), but the ratios of retweets to tweets, and of tweets per user, were in the normal range.

For #NDZ, the ratio of tweets per user was slightly elevated (2.3, where we would expect a range of up to 2.0), but the other indicators were in the normal range.

These variations do not indicate significant artificial manipulation; rather, they suggest the existence of dedicated activist communities pushing their candidates’ hashtags, but without larger-scale attempts to distort traffic.

The figures can be compared with two political hashtags which @DFRLab has observed in other environments, and which we know were artificially enhanced: #StopAstroturfing, in Poland, and #DigDoug, in the United States.

All the indicators on #NDZ and #CR17 were substantially lower than the sample hashtags. This does not exclude some degree of artificial inflation of the two South African hashtags, but does indicate that any such activity failed to substantially alter the overall pattern of traffic.

American-style bots

Nevetherless, two tweets from the same account appear to have been amplified by a small network (in the low hundreds) of suspect accounts. Both supported Dlamini-Zuma — one directly, the other indirectly, by attacking Ramaphosa and his hashtag.

Each tweet was retweeted hundreds of times. This is, in itself, unsurprising, given that the author, @Adamitv, had 154,659 followers as of December 19. The same account follows a remarkably high number of users — 128,000 — suggesting that its following is boosted by follow-back agreements.

The website for @adamitv has its ownership details hidden through PerfectPrivacy.com. The account’s activity includes retweeting @mngxitama, leader of the Black First Land First (BLF) group, who faces accusations of being paid by the Gupta family to spread misinformation, and posting pro-RET (Radical Economic Transformation) messages.

A close inspection of the accounts which retweeted its political posts suggests that many were bots, automated to retweet a range of messages.

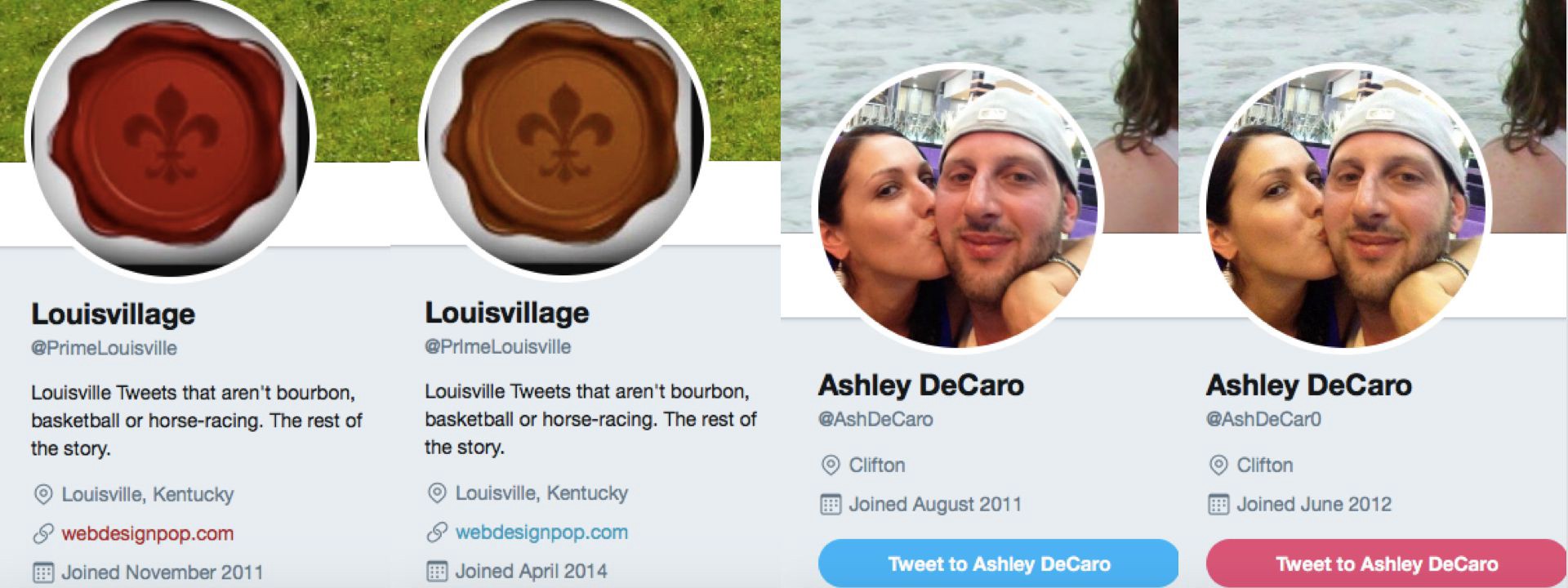

Accounts which retweeted the attack on Ramaphosa include @AshDeCar0, @PrlmeLouisville and @peyt0nle. All these appear to be American-based accounts, giving their locations in Clifton; Louisville, Kentucky; and Portland, Oregon, respectively. Most of the other accounts which amplified this tweet also gave American locations.

It is unusual for so many America-centric accounts to share tweets from a South African political account. The explanation is that these are fakes: copycat accounts imitating apparently genuine ones, stealing their posts from other users, and almost certainly automated.

Given that they are fakes, we cannot say for certain whether the person behind them is US-based. However, their primary language is English, their appearance is American, and their main focus is American events. We therefore view them as targeted at a mainly American audience.

Intriguingly, the accounts are old, having been created between 2012 and 2014, but they have only posted around 1,400 times each. This suggests that they have been operated at low volumes, to avoid detection by Twitter’s automated systems.

All their most recent posts are retweets. They cover a range of subjects, mostly US-focused and in English, but also including occasional posts in languages such as Czech, Arabic and Spanish.

This mixture of languages and themes is typical of commercial bots, rented out to amplify posts. Each retweeted a number of @Adamitv’s posts, suggesting that they had been hired — not necessarily by the unknown user behind @Adamitv — to amplify the account.

This network appears more sophisticated than most botnets which @DFRLab has encountered. Each account we investigated appears to be an almost identical copy of another Twitter account, but with one letter in the handle changed to a number.

For example, @AshDeCar0 is all but identical with @AshDeCaro, while @PrlmeLouisville is all but identical with @PrimeLouisville. The only difference is the letter/number switch in the handle.

Many other accounts in this series showed a similar pattern, with either an “i” in the handle being changed to an “l”, or an “o” in the handle becoming a “0”. Many of them were created in April 2014:

A few of these fakes have creation dates earlier than the accounts they were imitating, but still with the swap of an “i” or “l”, or an “o” or “0”, in the handle. This suggests that some of these bot accounts originally had different names, and were renamed at a later date:

One account even mimicked a group supporting returning US veterans with assistance dogs:

A search for authored posts from some of the bot accounts (search terms “from:megklnd”, “from:PrlmeLouisville” and “from:peyt0nle”) showed that each had only posted a few times, all on the same day, several years ago, and then fallen silent. Many of them, though not all, did so on April 22, 2014.

A search for the exact words used in these tweets revealed that they had been tweeted by other accounts first. This suggests that the bots had been set to copy genuine tweets at the start of their lives, to make them look more authentic:

Accounts such as these, with apparently American identities, made up a very large share of the retweets of @Adamitv’s post. While an eyeball scan cannot identify every account, the clear majority of retweets appears to have come from this network, putting the number of accounts involved in the low hundreds.

Conclusion

These bots did not have a major distorting impact on the Twitter traffic, still less the ANC’s internal decision-making process. They are chiefly of interest for the sophistication with which they were created, and the way in which they have lasted so long.

However, their presence in the debate which preceded the ANC decision should serve as a warning. These bots are relatively skilfully made, and have lasted an unusually long time — probably because of their low posting rates and the way in which they stole real user profiles.

South Africa is about the enter the most heated part of its electoral cycle, as the countdown begins to presidential elections, and the replacement of President Zuma, in 2019.

We can expect bot herders to attempt to manipulate social-media traffic, and influence voters, as the countdown continues. The sophistication of this botnet suggests that South Africans will need to be on their guard against more, and more sophisticated, fake accounts.

This article was the result of collaboration between ANCIR, @Code For Africa and @DFRLab.