#ElectionWatch: Pushing Back On Putin?

Social media traffic as Russians sign up for Putin’s re-election

#ElectionWatch: Pushing Back On Putin?

Social media traffic as Russians sign up for Putin’s re-election

On January 14, supporters of Russian President Vladimir Putin began proclaiming their support for his re-election bid with the hashtag #РоссииНуженПутин (Russia needs Putin).

The campaign was promoted, and largely driven, by the United Russia party, which Putin long headed, although he is running for his fourth presidential term independently of the party. It centered on Russian citizens signing up to Putin’s official candidacy: under Russian law, any candidate needs 300,000 signatures. By January 16, Putin reportedly received over one million.

Putin is popular in Russia, and retains the support of the nationwide United Russia party apparatus, so there is nothing intrinsically implausible with the figure. However, as the BBC pointed out, the hashtag itself was by no means universally acclaimed, with some users — a minority, but a vocal one — utilizing the hashtag to criticize Putin and the state of Russia under his long rule.

The presence of such a minority is significant going into the elections, not so much as an indication of a viable opposition — Putin can be expected to win by a crushing margin — but because such social media users played a crucial role in amplifying claims of election fraud at his last re-election, in 2012. Much of the Kremlin’s efforts over the past six years appear to have been aimed at preventing a repeat: social media are likely to be a particular battleground on election day.

@DFRLab analyzed the traffic on Twitter, Facebook and Russian platform VK to assess the scale of Putin’s support, and the criticisms.

Party backing

The hashtag #RussiaNeedsPutin has a long history, having circulated on social media before Putin’s last election, in March 2012:

On January 14, the hashtag resurfaced as Putin supporters began posting selfies of the moment they signed up for his renewed candidacy:

Despite the fact that Putin is running as an independent, many posts used United Russia hashtags, including its initials (ЕР in Cyrillic) alongside the Putin one.

The hashtag cut across channels, also picking up traction on Russian social network VKontakte (VK or ВКонтакте).

The following post was made by a United Russia party leader from Kursk, who also re-posted a photograph of himself with the party flag.

The hashtag also spread to Facebook, where, again, users attached it to photos of themselves supporting Putin.

Facebook also featured a Putin supporters’ group in the Tambov district; many of its members reset their profile pictures to show the hashtag.

Despite this visual similarity, the great majority of these accounts appeared to belong to genuine users in the Tambov area. Their pages are not public, meaning that detailed information about their backgrounds (including where they work, and whether they are party members) is unavailable; however, former posts give sufficient indications as to their varied family lives, hobbies, and friendship circles that they are unlikely to be fake accounts.

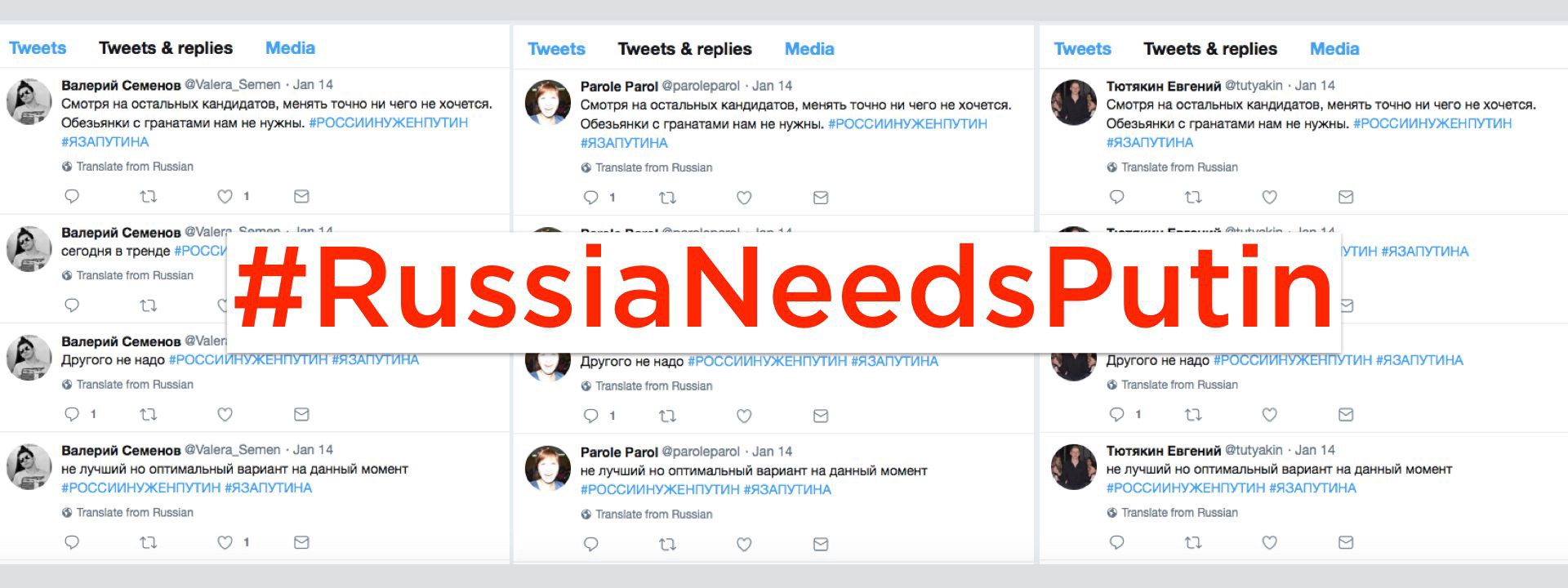

On Twitter, more automated traffic was apparent. Some uses of the hashtag do appear to have been generated by automated “bots”, which all shared the same wording at the same time, as the following search indicates.

This small cluster of accounts repeated the same posts, in the same order, at the same time — classic indicators of automation.

However, the overall spread of the hashtag appeared to have been largely the result of a combination of party discipline and genuine public activity, with bot activity only representing a fraction of the whole.

For example, the tweet by party official Dmitriy Platonov, quoted above, was reposted 32 times. Its retweeters included five separate United Russia subdivisions in the area, as well as various local United Russia leaders.

A number of local officials also shared posts on Facebook. For example, Vladimir Yeliseyev, the head of the Znamenskiy district in Tambov region, reposted a large number of pictures of people signing for Putin.

The hashtag campaign achieved modest success on social media. As of midday on January 16, it registered just over 10,000 tweets, according to a machine scan. Data on Facebook and VK are harder to come by; a significant number of Facebook posts scored reactions in the 200–300 range, and shares in the 50–100 range. These figures show some, but not massive, penetration.

Pushing back

Not all reactions lavished praise on Putin. Perhaps the most striking was a VK post from the Tambov region, which subverted the hashtag by claiming that “Russia needs Putin, but the people of Tambov need roads”.

The post, and accompanying video, urged users to post pictures of potholed roads around Tambov, and to use the hashtag to draw attention to their plight.

https://vk.com/video1884123_456239122?t=30s

This video was viewed 970 times by January 16; in the final seconds, the narrator said that the “Russia needs Putin” hashtag had been launched by civil servants (чиновники), while the Tambov hashtag was a call to, and from, normal people. This claim was corroborated by the open source evidence, which showed how important the party was in spreading the hashtag.

Another video clip, filmed going along a potholed road, but undated, and describing how badly the road had deteriorated, was viewed over 18,000 times by January 16.

The appeal had at least local resonance. By January 16, one post collecting three photos on VK was viewed 1,500 times.

By January 15, a second group, in the Republic of Mordovia, joined the campaign and launched its own parallel slogan, “Russia needs Putin, but the people of Mordovia need roads”.

The references to “agitprop” (агитпроп, agitation propaganda) are especially interesting, as they show direct criticism of the #RussiaNeedsPutin campaign, but only an indirect response — highlighting a local problem, rather than attacking the once and (presumably) future head of state head-on.

Other comments on other platforms were more aggressive and appeared to achieve some traction.

This post on VK, for example, added the hashtag #WeWantChange2018 (#ХотимПеремен2018) and shared a meme and video from YouTuber Dmitry Ivanov (YouTube name KamikadzeDead). The original VK post gained 18,000 views, and the video 212,000 views, in 24 hours.

The hostile posts were not limited to one channel.

Judging by the numbers of retweets and likes, these posts did resonate within particular audiences. They did not achieve the spread or the numbers of the pro-Putin posts, but they were an active minority.

One of the more interesting exchanges came from this pro-Putin tweet, which showed the account holder signing up for Putin’s candidacy.

The account was attributed to Alexey Ponimatkin. It was created in December and only has nine followers; the name was also attributed to a VK account which featured some of the same photographs, but only has three followers. The VK profile picture shows the user standing in front of a banner for the All-Russia Popular Front, which Putin created in 2011.

Ponimatkin’s tweet was first retweeted by Sergei Boyarskiy, a member of the Russian State Duma (parliament) and, according to Boyarskiy’s own Twitter profile, both a member of United Russia and the coordinator of the All-Russia Popular Front’s youth wing. This, therefore, appears to be another case of party members spreading the message.

However, while Ponimatkin’s tweet earned nine retweets, it also received 38 replies, the great majority of them hostile.

Some users tweeted more than one reply; this one even shared a video dated back to 2011, titled, “Our madhouse is voting for Putin”.

The sheer number and variety of replies, and the number of users involved, suggested a high degree of alertness among Putin’s online critics, and a willingness to launch their own troll attacks. It may also indicate some form of coordination. Finally, the fact that replies outnumbered retweets four to one indicated that, at least in this one instance, Putin’s critics were able to match his supporters.

Conclusion

The collection of signatures has been a personal success for Putin: the reported figure of over one million is a major public relations victory. However, the online traffic tells a more nuanced story.

While much of his support is no doubt genuine, the online traffic was modest, and driven by the nationwide apparatus of the United Russia party and its various local subdivisions; this is strikingly similar to the role played by mid- and low-level Communist Party managers in Soviet times.

Opposition to Putin, and to the system he embodies, was not on the same scale as the support, but it seems to have struck an organic chord. The complaints about roads inspired at least one copycat movement; the reference to “agitprop” again harkens back to Soviet times.

Accusations of corruption continued to circulate online and to receive tens of thousands of views, and Putin opponents appeared to be sharpening their own trolling techniques.

This is significant for the implications for voting day itself. There can be no doubt that Putin will win handsomely; what will matter is the nature of his victory. In 2011–12, Russia’s elections were marred by highly visible cases of election fraud, many of which were filmed live and posted on social media. The traffic on the #RussiaNeedsPutin hashtag shows that there remains a vocal online community opposed to Putin and determined to highlight his government’s shortcomings. This is precisely the constituency which can be expected to amplify any claims of fraud at the forthcoming vote. The voting itself is predictable; the online reaction is not.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.