#ElectionWatch: Graphic Preference from Russian Media in Latvia

How Russian language media in Latvia visually frame political parties before elections

#ElectionWatch: Graphic Preference from Russian Media in Latvia

How Russian language media in Latvia visually frame political parties before elections

Russian state-owned media outlets in Latvia showed a clear preference in visual representation towards so-called “Russian” parties in Latvia ahead of the Baltic state’s parliamentary elections, which are due to take place on October 6.

This bias was not replicated by Russian-language outlets in Latvia, which remain independent of the Russian government. The systematic bias in reporting from Russian government-funded outlets is significant, particularly ahead of elections, because 19.5 percent of Latvian citizens are native Russian speakers.

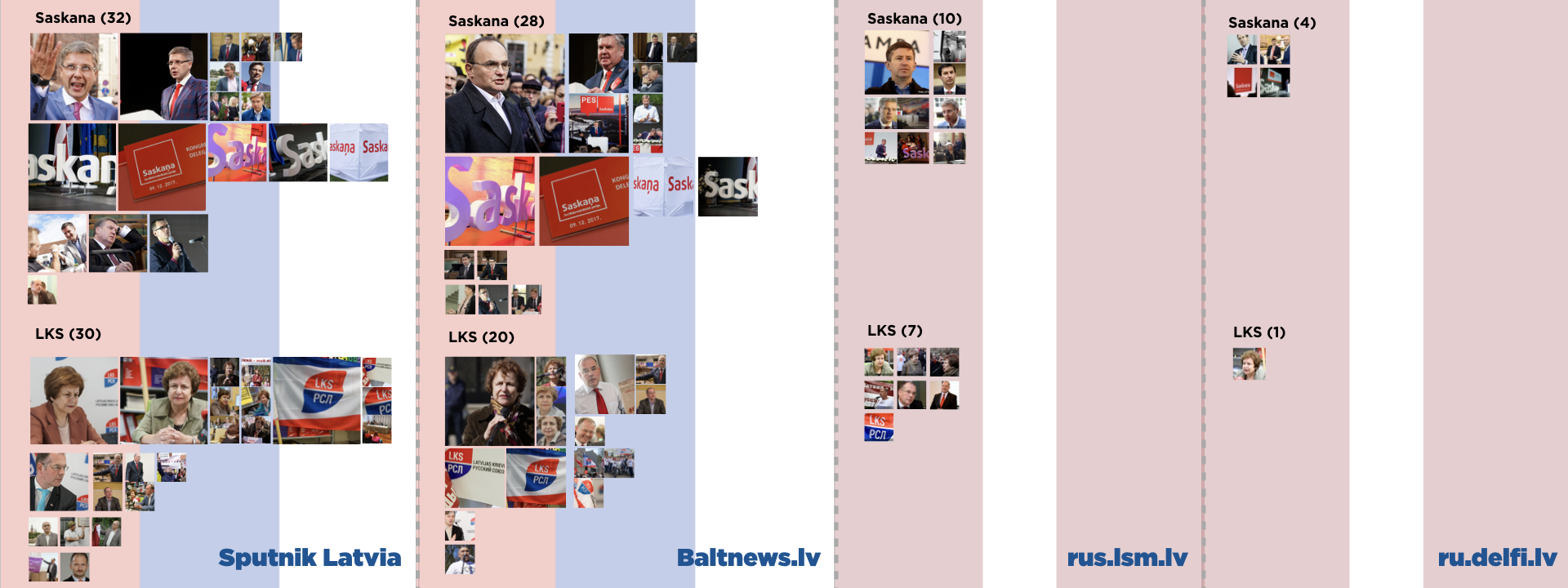

Almost every sixth visual Sputnik Latvia and Baltnews.lv used for election coverage in Russian language were about Saskana (The Harmony party), which used to have a contract with Russia’s majority party “United Russia”, and Latvijas Krievu Savieniba (LKS or “Russian Union of Latvia”). The visual exposure of a particular party was less evident on the Russian language version of LSM.lv, the Latvian state-financed media outlet, and the Russian language version of Delfi.lv, the largest privately owned online news portal in Latvia.

The Visual Preferences

@DFRLab carried out visual content analysis to measure how the most relevant Russian-language media in Latvia used images in election coverage. According to Robert Entman, the author of the book “Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and US Foreign Policy” images frame a reader’s world view by explaining events and providing recommendations.

All four media outlets that were analyzed had a special section dedicated to the upcoming elections.

LSM.lv is the Latvian public broadcaster. Delfi.lv is an independently-owned news portal, and the most heavily trafficked online outlet in Latvia. Sputnik and Baltnews.lv are both owned by the Russian state’s Rossiya Segodnya agency. Baltnews’ connection with the Kremlin, and the control exerted over it, was recently exposed by investigative journalists.

Sputnik Latvia created a section for the elections in both Latvian and Russian languages. The topic in Latvian translated to “Election racetrack”, while the topic in Russian translated to “Latvian parliamentary elections — 2018”. The number of articles for each topic was also different. The local version of Sputnik published 80 news stories under this topic in Latvian and at least 218 news stories for the same topic in Russian before September 13. @DFRLab analyzed only the election section in Russian.

Baltnews.lv also had a section dedicated to the Latvian elections, which contained 188 stories.

The Russian language version of Latvian state-financed LSM.lv published 190 stories in the election news section.

Delfi.lv named its Russian-language section for the elections “Your Vote Matters!” as translated from Russian. It contained just 31 news stories from this year, starting from August 7. The rest of the stories in this section were about the elections that took place in 2014.

@DFRLab compiled the images that contained logos or representatives from the political parties which are running in this election. The sentiment of the articles these images illustrated was not analyzed, as the aim was to identify if media outlets carried out disproportional coverage of one or another political party.

The comparison showed that the Russian state-funded outlets used a disproportionate amount of imagery in their coverage of LKS — far more than did either of the non-Russian government outlets. It also showed that LSM.lv used images of more parties than other Russian-language media, suggesting an editorial decision to cover all aspects of the election.

Both Russian government media outlets used images about Saskana and LKS more than about other parties. The same images with the party logos and the party leaders were re-used several times by both Sputnik Latvia and Baltnews.lv. @DFRLab scaled the images that were used more than once larger, proportionate to their use.

Images that contained a politician or a logo of a political party were used less than half of the time in all Russian language media outlets.

The data showed that images related to Saskana were used the most across all four platforms, which is logical, given its leading position in opinion polling. @DFRLab has previously reported that Saskana moved away from Putin’s “United Russia” party and joined the Party of European Socialists (PES). Sputnik and Baltnews dedicated a higher proportion of their coverage to Saskana than Delfi, but not to a significant extent.

The main difference in coverage was in the use of images referring to LKS, the Russian Union of Latvia. This was the second most visually represented party on both Sputnik Latvia and Baltnews.lv, accounting for almost one third of all imagery, despite the fact that the party polled only 0.2 percent of voting intentions in September. Its visuals were used almost four times more than on LSM.lv and Delfi.lv.

In comparison, the Latvian state-funded media used visuals associated with a political party just third of the time. The ratio of how many times each party was highlighted using visuals was more equal. LSM.lv covered four less popular parties that were not mentioned on other Russian language media outlets, showing the widest selection of visuals.

The two parties LSM.lv portrayed most were the poll leaders, Saskana and ZZS (the Greens’ and Farmers’ Union). It used a visual from LKS once, but also used visuals from other parties polling below the five-percent barrier. LSM.lv’s use of imagery was broadly in line with the weight of each party in the polls; the one lack of proportion appeared in an under-representation of the Latvian nationalist National Alliance, polling third, but only visualized once.

Promoting the Underdog?

Based on September polling data, in which LKS was tipped to gain just 0.2 percent of votes, it appears unlikely that the party will gain parliamentary representation. The coverage of LKS on both Kremlin media outlets appeared highly disproportionate, suggesting a desire to make the party more visible to Russian speaking voters.

The most recent issue connected with LKS before the elections was the fact that the Latvian Central Election Commission (CVK, after its Latvian acronym) forbade the party’s leader Tatyana Zhdanok to participate. The decision was based on a law that forbids participation for people who were members of the Communist party after 1991, the year when the country regained its independence.

This decision was broadly covered. LSM.lv published three stories about it — one about CVK’s decision, one about the possible decision of the Constitutional Court and one about the final decision of the court not to allow Zhdanok to participate in the elections. In comparison, Sputnik Latvia published seven stories about the same issue. Sputnik wrote not only about CVK’s decision, but also about the fact that CVK needed time to make it, and about the reasons for the ban. Sputnik also wrote about Zhdanok’s interview to Russian state newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta about the ban and explained why Zhdanok applied if she knew about the ban. Sputnik wrote about Zhdanok’s appeal to the Constitutional Court, the court’s decision and a feature article about the ban. The news articles were fact-based and did not use editorial statements. The feature article suggested that the ban was politically motivated, because Zhdanok “was too active”. The lead sentence read:

Tatyana Zhdanok defends interests of voters too actively and threatens Latvia with something secret, the Administrative district court thinks.

Sputnik Latvia also wrote articles about the party’s pre-election performance. First, Sputnik called LKS lucky for getting the first number on the voting ballot. Second, Sputnik published two articles explaining the low performance of LKS in opinion polling. In one article Sputnik claimed that LKS voters are shy to admit that they support the party. In the other article, Sputnik explained how many election polls are different and LKS’ chances for the elections.

At the same time, though both Russian state-owned media outlets mentioned Saskana repeatedly, many articles were critical. Another leader of LKS, the former member of Saskana Andrejs Mamikins published a Facebook post which stated that Saskana was silent when protecting the interests of the Russian language activists. Sputnik picked the post up and used it in an article. Sputnik did not reach out to Saskana representatives for any statements on the matter to make the article more balanced. Mamikins also told Baltnews.lv his bad experience while being Saskana member. The format of the article was interview, so no Saskana perspective on Mamikins was mentioned. Later Baltnews.lv reported that Saskana recognized Russia’s annexation of Crimea and published a skeptical article about Saskana’s chances of winning the parliamentary elections.

Conclusion

Russian state-owned media outlets Sputnik Latvia and Baltnews.lv used many more images in their reporting on the two so-called “Russian parties” than the popular Delfi or the Latvian state-financed media outlet LSM.lv.

The case study about Zhdanok’s ban to participate in the elections showed that Sputnik granted more coverage to the issue than LSM.lv.

The visual content analysis of Baltnews.lv’s coverage about Saskana and LKS identified critical reporting about Saskana. Sputnik Latvia also showed preference to LKS in its reporting.

The disproportionate number of stories that used images associated with Saskana and LKS suggests that Russia has a vested interest, through its state-owned outlets, in an attempt to narrow the choice for Russian speaking voters in Latvia ahead of elections on October 6.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.