#ElectionWatch: Social Media Hack on Latvian Election Day

How social media and online media outlets reacted to the hacking of Latvian social network Draugiem.lv

#ElectionWatch: Social Media Hack on Latvian Election Day

How social media and online media outlets reacted to the hacking of Latvian social network Draugiem.lv

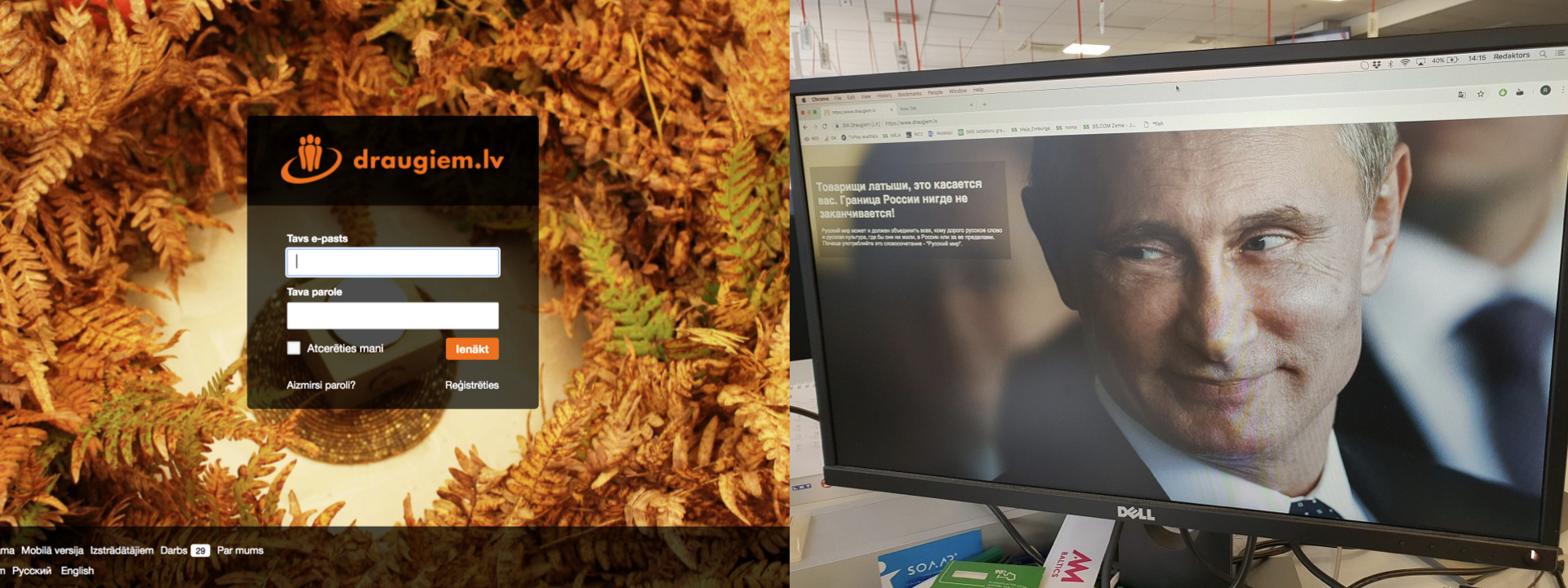

During Latvia’s parliamentary election day on October 6, the sound of the Russian national anthem and images of the Kremlin, Vladimir Putin, the Russian flag, and a Russian soldier appeared when opening the front page of Latvian social network Draugiem.lv. The hacking attack was confirmed by Draugiem.lv spokesperson Janis Palkavnieks.

Latvia has a troubled relationship with its neighbor Russia, leading to fears that the Kremlin might attempt to interfere in Latvia’s election. In particular, Russian-language and pro-Kremlin media regularly report on relations between ethnic Latvians and Russians in a potentially inflammatory way, deepening the potential for social conflict.

The hacking made news in Latvian, Russian, and English language media. Media outlets in Russia did not spin the event and provided fact-based coverage, while social media users suggested different theories.

The event did not include user data and did not affect the election results. The case demonstrated resilience across Latvian society in the face of the potential for electoral interference, as well as disinformation on social media more broadly.

The Hack

Draugiem.lv was the first social network in Latvia founded in 2004 by Latvian entrepreneurs. It has been the tenth most visited webpage in Latvia in 2018.

The first Latvian media outlet to report about the hack was Skaties.lv. Its publication consisted of photographs of a computer screen and a short video that recorded the Russian anthem that was playing in the background.

The users of the Draugiem.lv social network also reported the hack.

The text in Russian placed in the top left corner said:

Latvians, it affects you. Russia’s border never ends! The Russian world can and should unite all those who treasure the Russian name and culture wherever they live — in Russia or beyond its borders. More often, you use the string of words — ‘The Russian world!’

An hour after the attack, Janis Palkavnieks, the Draugiem.lv spokesperson, confirmed that the hack happened. Two and a half hours later, he reported that the social network was back up and the user data had not been compromised as a result of the hack.

An hour before polling stations were closed, Latvian public broadcast media LSM reported an official statement by Information Technology Security Incident Institution “CERT.lv”, which investigated the hack. The statement read:

The current examination did not indicate that an intrusion would have led to a data leak. The investigation found that the attackers used IP addresses of Asian countries, but this does not allow for unambiguous conclusions about the source of the attack, because the attack may have used hacked equipment.

Reactions on Social Media

@DFRLab investigated the sentiment toward the event expressed by social media users in Latvian and Russian languages.

Most of the tweets in Latvian suggested that anti-Russian political parties benefited from the event the most.

The first post regarding the incident on Russian social media platform ВКонтакте (VKontakte or VK) appeared on the evening of October 6 and carried into October 7.

Despite the relatively large number of posts, they were not highly engaged. Only a few of these posts garnered up to 22 likes and a few shares, while the majority gathered none to a few likes. These posts did not spark any major discussions in the comment sections either, suggesting that Russian speaking VK users were not highly interested in the event during their Saturday evening.

Most of the VK posts quoted excerpts from the articles covering the event, quoting objective facts of what happened. Nonetheless, two other main groups of users were identified: those who made fun of the Kremlin and blamed it for the hack, and those who blamed the Latvian government for setting up a false flag operation. The posts of both of the groups failed to garner large numbers of likes or shares.

The first group, which included a smaller group of VK users, argued that this incident is the Kremlin’s doing and mocked Putin by calling various names him, as the “Botox Führer” and the GRU agents as “chepiga’s”, a referenceto the investigation that suggested a colonel of GRU Anatoly Chepiga to poison Russian double agent Sergey Skripal and his daughter (originally reported by @DFRLab’s partners at Bellingcat).

The other group of VK users raised conspiracy theories and claimed the hack was a false flag operation by the Latvian government to help elect a set of preferred anti-Russian candidates.

Russian-language Media Coverage

A similar narrative was observed in Russian media coverage. The first media coverage in Russian language was by Latvian and one Estonian media outlet. Media reported the fact of the attack that had already been covered by Latvian media outlets in the Latvian language.

One of the most shared articles on VK was published by Lenta.ru, which presented the facts of the attack objectively without clear bias. The article, similar to many VK posts stated that the source of the attack had been investigated at that time. Most of the shared articles depicted the situation objectively without irony or bias.

Nonetheless, Sputnik News’ outlet in Latvia made a somewhat ironic note in its Russian-language coverage. Sputnik argued that some sources already blame the “Russian hackers”, writing these words in quotations. In fact, the article compiled three tweets expressing different versions about the attack. One tweet suggested that it was Russian hackers. Another tweet called it a public relations campaign by Draugiem.lv themselves. The third tweet suggested that someone wanted to scare people.

A few ironic comments were also available under some of the articles, rhetorically asking if this is the doing of GRU agents again.

Conclusion

According to official statements, the hack did not compromise user data and in no way impacted the results of Latvia’s parliamentary elections.

@DFRLab identified mostly fact-based reporting about the event both in Latvian and Russian languages.

No high confidence assessments of attribution behind the attack are currently available, and social media users did not share a common idea of who was behind the event. The posts in Latvian language mostly pointed out that the hack contributed to anti-Kremlin parties in Latvia. VK users other shared exerts from the articles, made fun and blame of Kremlin for the incident or blamed Latvian government for the false flag operation.

As of now, it seems that the Russian media and social media coverage failed to interest their readers with the event. Despite the extensive Russian media coverage and amplification by the VK users, the engagement stats remain relatively low.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.