Facebook’s Sputnik Takedown — In Depth

Inauthentic pages linked to Sputnik promoted its content

Facebook’s Sputnik Takedown — In Depth

Facebook removed almost 300 pages from its platform for “coordinated inauthentic behavior” across the former-Soviet space on January 17, 2019. The pages masqueraded as groups with special interests — ranging from food to support for authoritarian presidents — and amplified content from the Kremlin’s media agency, Rossiya Segodnya, especially that of its subordinate online news outlet Sputnik.

The pages represented a systematic, covert attempt to improve Rossiya Segodnya’s online audience across more than a dozen countries. Some had little impact, but others racked up tens of thousands of followers. Sputnik was the main beneficiary, as it was often the only source the Facebook pages amplified.

The Editor-in-Chief of Sputnik Latvia, Valentīns Rožencovs, confirmed that Sputnik ran the Latvian-focused pages. Open-source evidence shows that Rossiya Segodnya employees ran some of the other pages and were aware of even more of them.

In addition to a previous, independent investigation by @DFRLab, Facebook shared the names of the accounts before the takedown. Based on internal evidence, not shared with @DFRLab, Facebook concluded:

Despite their misrepresentations of their identities, we found that these Pages and accounts were linked to employees of Sputnik, a news agency based in Moscow, and that some of the Pages frequently posted about topics like anti-NATO sentiment, protest movements, and anti-corruption.

@DFRLab’s accompanying post presents the main findings. This article sets out the evidence behind those findings, under the following sections:

- Cross-border operation;

- Fan pages and special interests;

- In Latvia, run by Sputnik;

- Rossiya Segodnya connections;

- Cross-posting;

- Amplifying Sputnik;

- Amplifying TOK;

- Audience;

- Creation dates; and

- Covert to fraudulent.

Cross-Border Operation

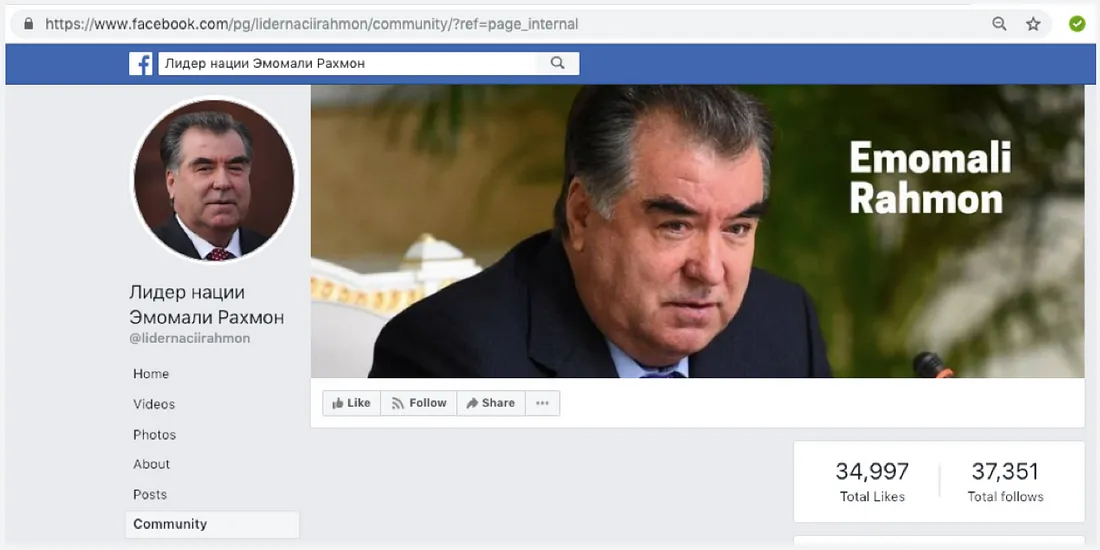

This operation reached across borders. For example, one page, dedicated to the president of Tajikistan, was run from Russia. Another page claimed to be run by “fans of [Uzbekistan President] Shavkat Miromonovich [Mirziyoyev], as the spiritual and national leader.” It was created three weeks after the Tajikistan equivalent, and it, too, was run from Russia.

International cross-posting within a media organization’s various local services is itself, of course, innocuous. This specific case is of note because of the role the inauthentic pages played in further promoting the traffic.

Fan Pages and Special Interests

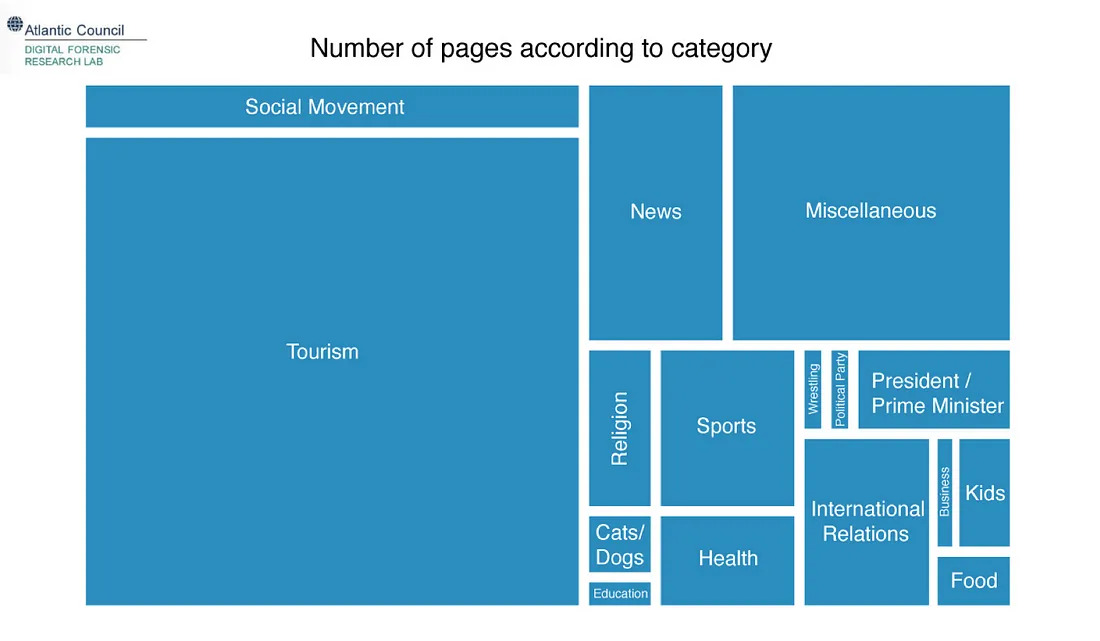

Most of the pages posed as special-interest groups covering a wide range of issues. These included tourism and weather (the most popular topics), food, fashion, beautiful women (but not beautiful men), pets, sport, culture, and various politicians.

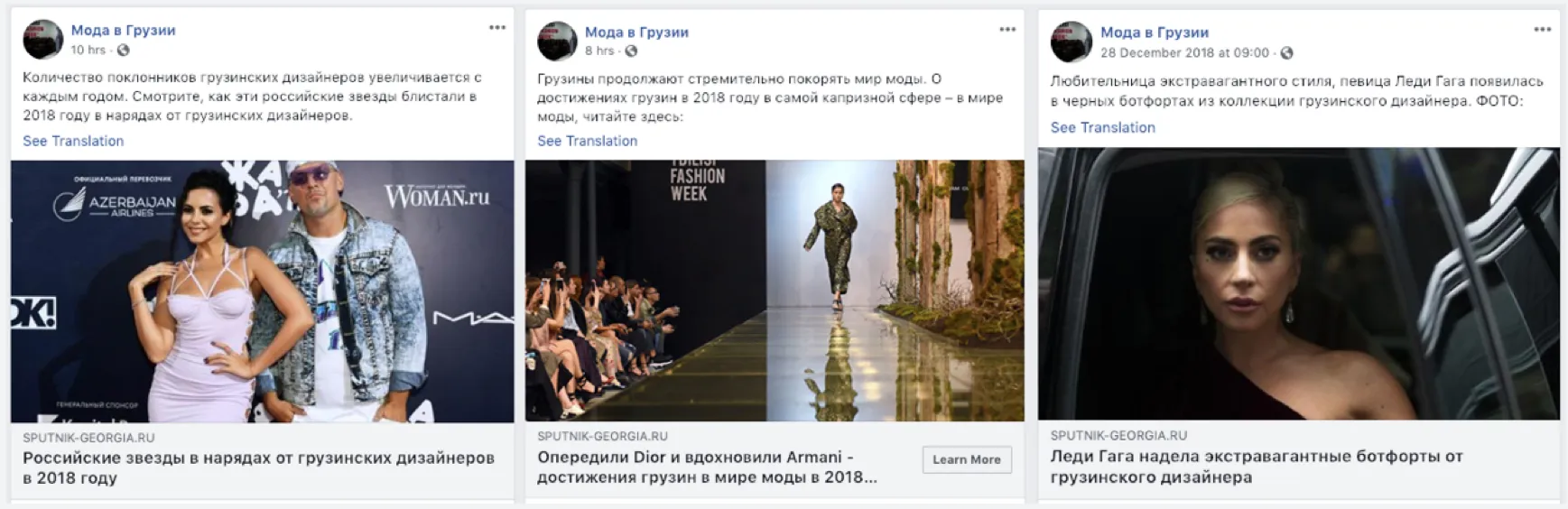

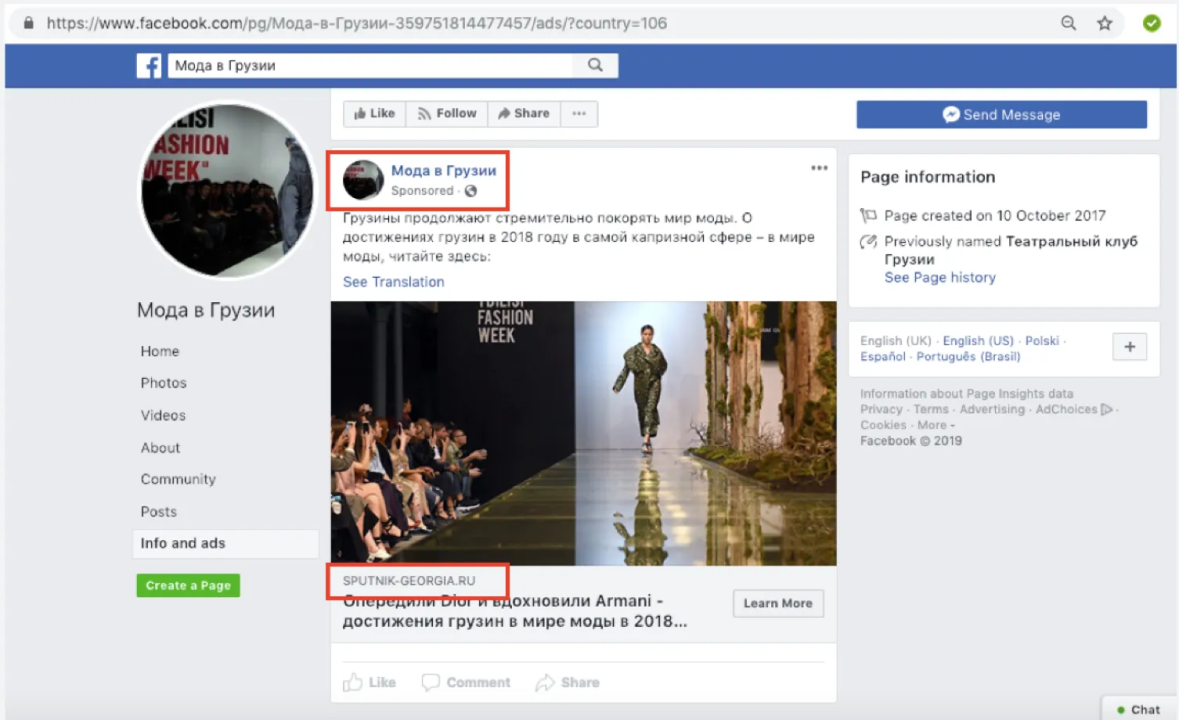

The pages largely posted content appropriate to their apparent sphere of interest. For example, a Georgian page ostensibly devoted to fashion primarily posted Sputnik Georgia articles about fashion.

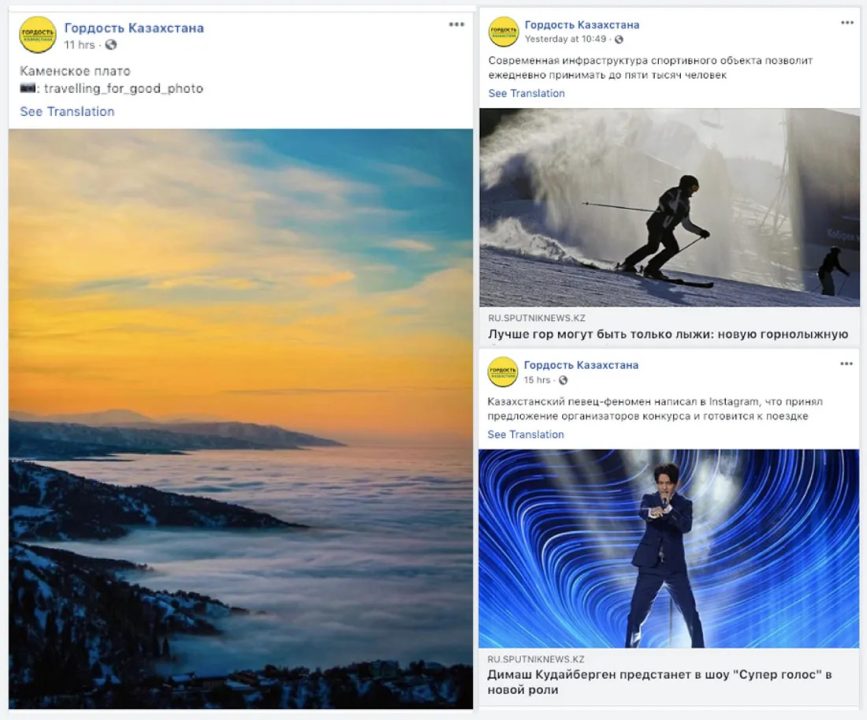

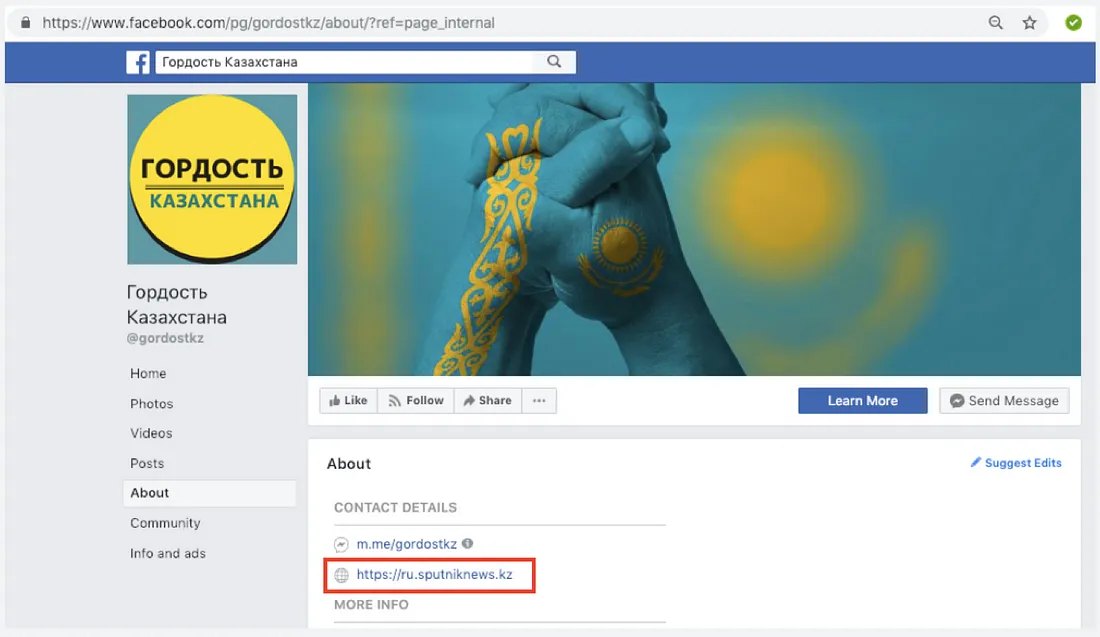

A page dedicated to “everything we are proud about” in Kazakhstan alternated between Instagram photos of scenery in Kazahstan and Sputnik Kazakhstan articles about Kazakh celebrities.

Some of the pages dealt with more political themes. Some posed as fans of the presidents of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and the former’s son, the mayor of the capital city, Dushanbe. These were predominantly positive in tone. Others focused on the presence of NATO and the situation of ethnic Russians in the Baltic States and were predominantly negative.

Overall, the network’s main effect was to promote Rossiya Segodnya content. Its secondary effect was to amplify Kremlin messaging on certain political themes.

Cross-posting

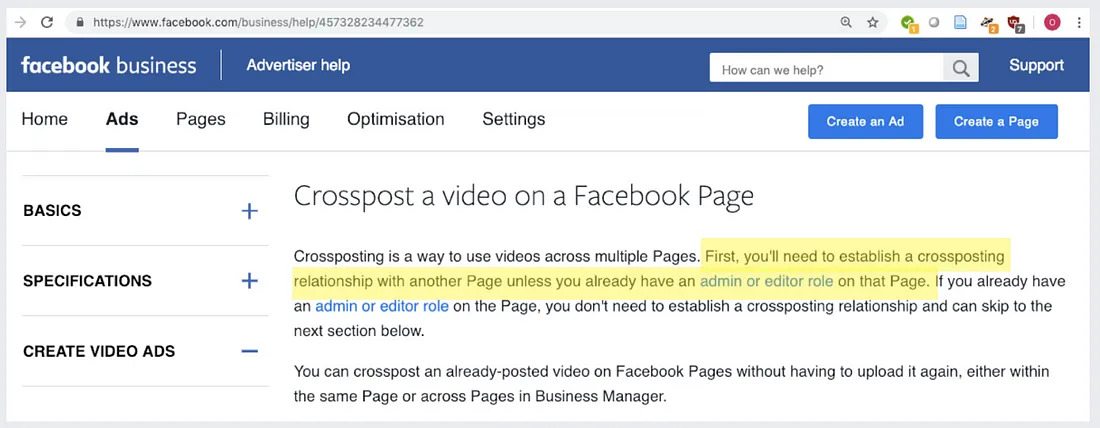

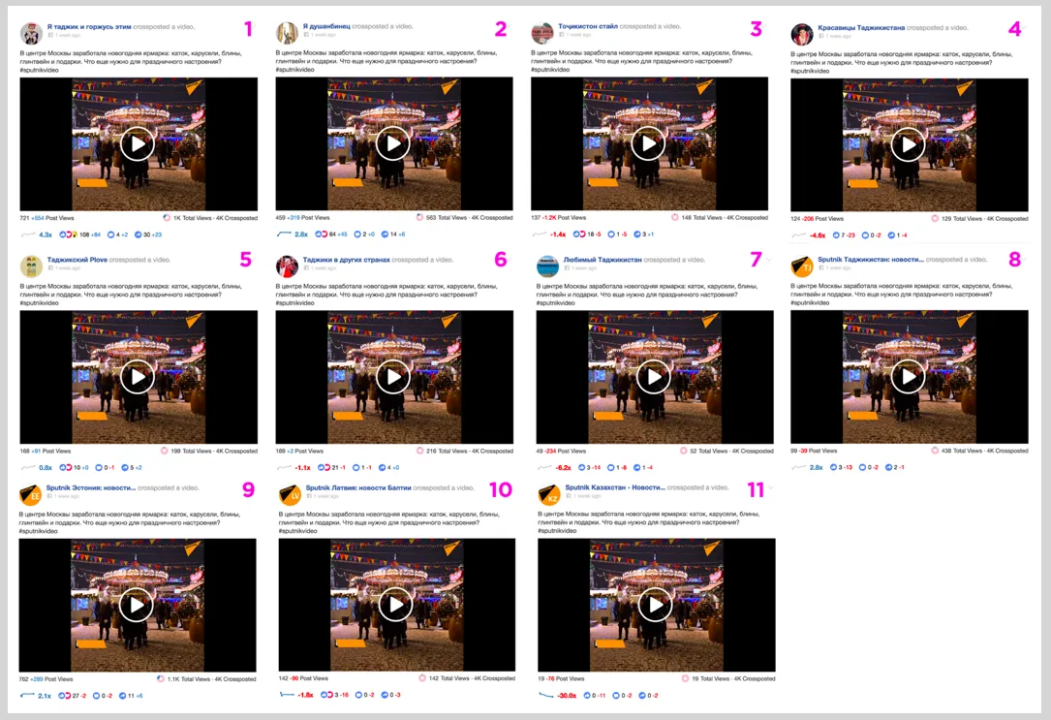

Many of the pages deemed inauthentic cross-posted videos from Sputnik or, to a lesser extent, a video service called TOK, which is also part of the Rossiya Segodnya portfolio (see “Amplifying TOK” below). Facebook introduced cross-posting as a way of making it easier to post videos. Accounts can only cross-post one another’s content if both agree to it or if they already have an administrator or manager in common.

Cross-posting therefore proves that there is a relationship between two pages, either in the form of an agreement to cross-post or of having a manager or administrator in common.

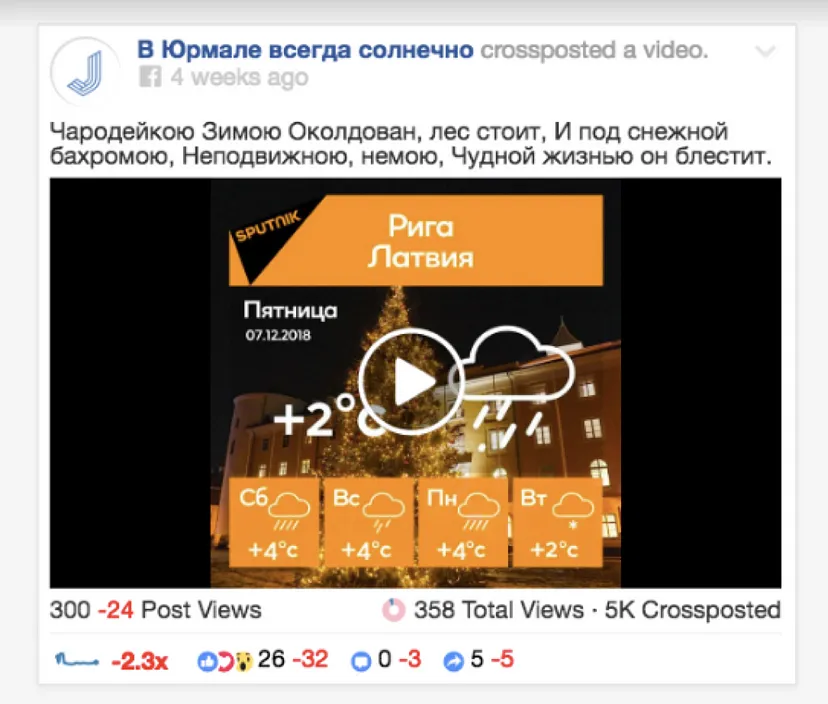

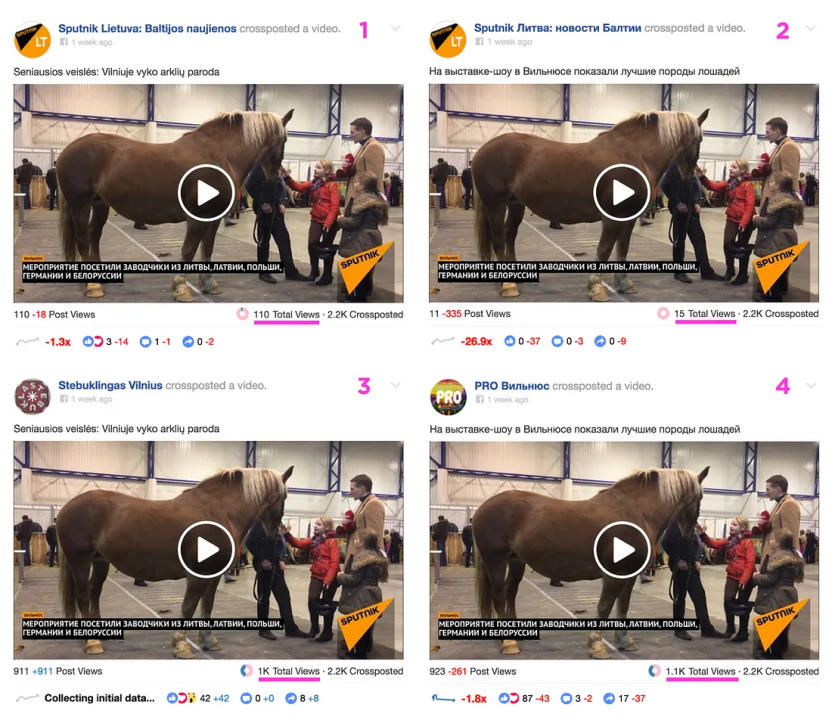

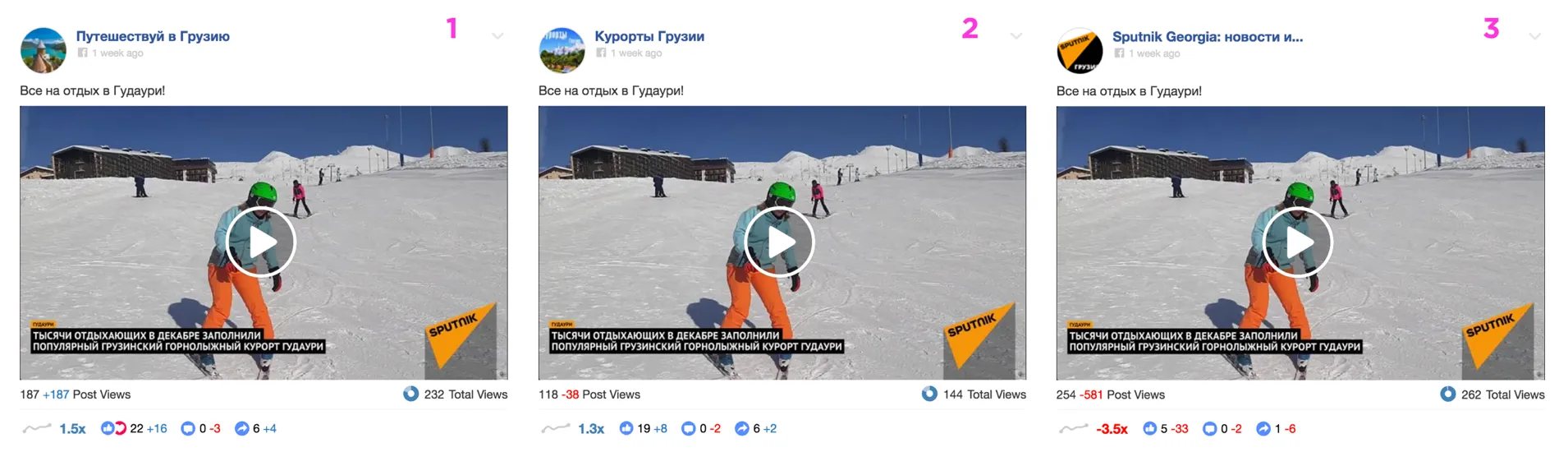

Users can identify cross-posting by using the CrowdTangle analytical platform, as in these examples, which show the inauthentic pages cross-posting Sputnik content.

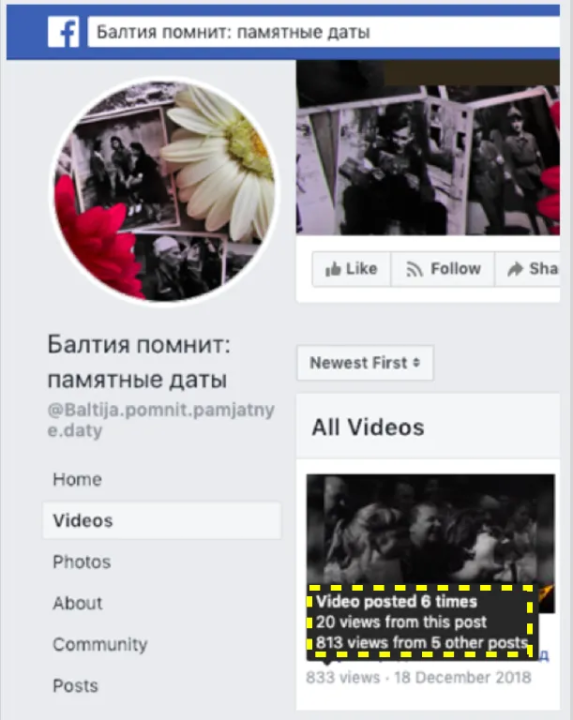

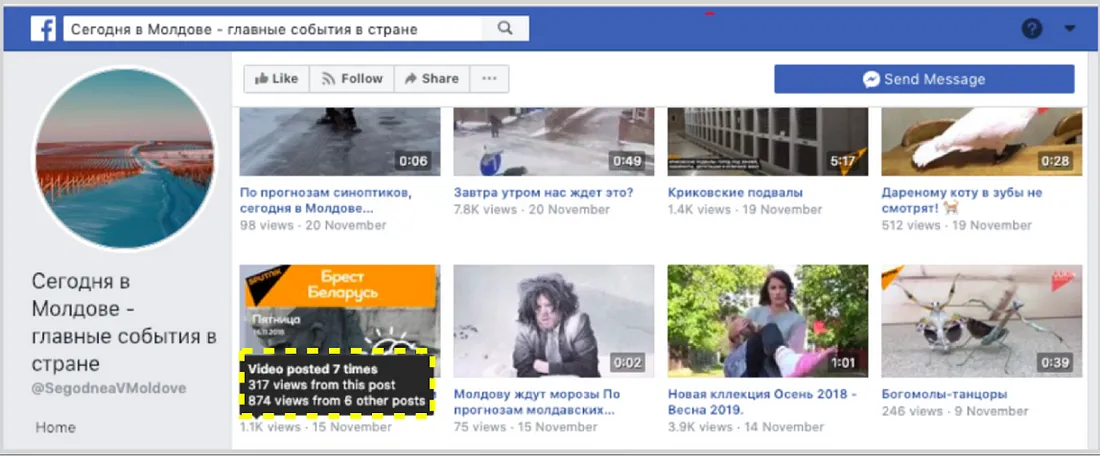

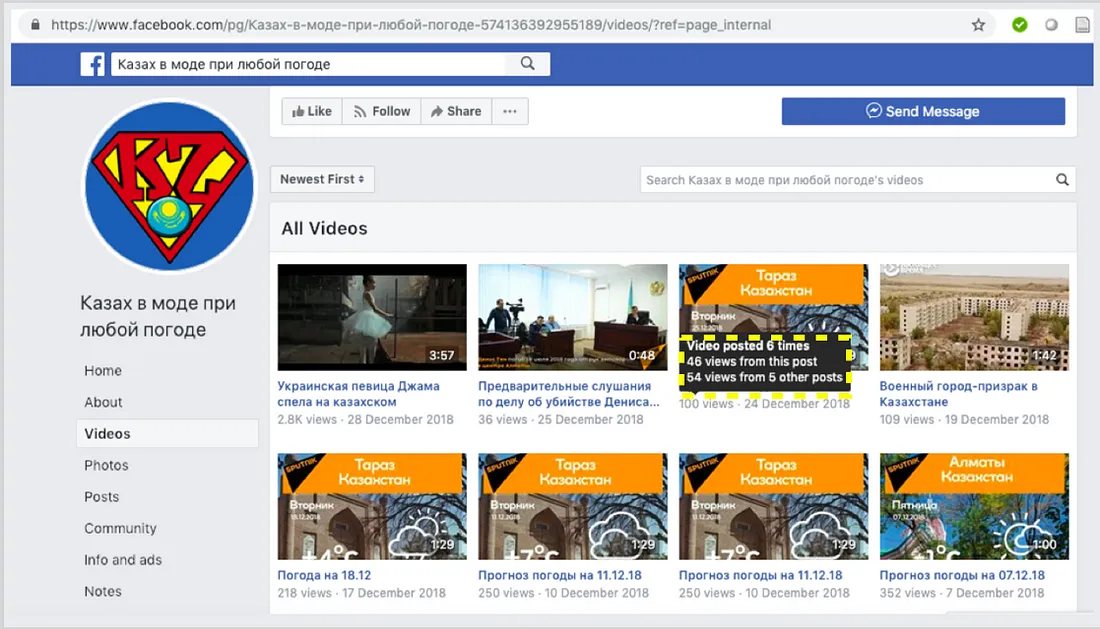

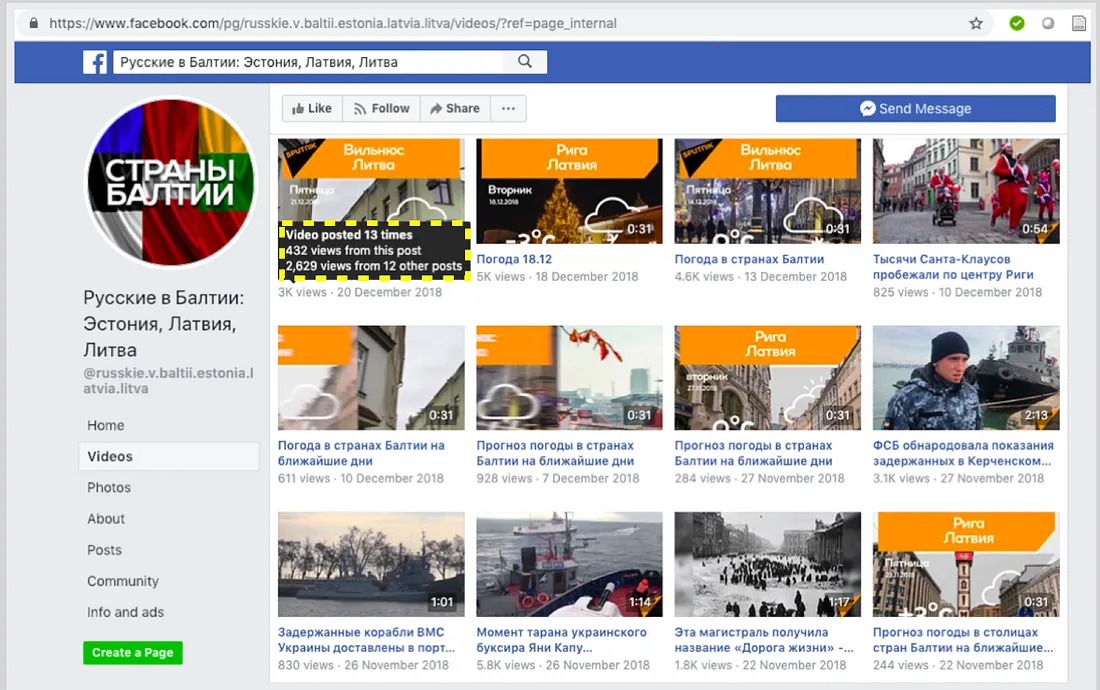

Users without access to CrowdTangle can identify cross-posting by hovering the mouse over the number of views a video has. If a box pops up showing the number of different shares of the video, it was cross-posted, as in the below examples from the takedown set, pulled from accounts focused on the Baltic States, Moldova, and Kazakhstan.

@DFRLab identified different patterns of cross-posting and sharing videos between these pages. Comparing Sputnik pages and pages in the inauthentic network, the latter seemed to gain significantly more impact, as the below graphic demonstrates.

In other cases, different pages in the network appear to have uploaded the same Sputnik videos separately, as in the case of this video about skiing in Georgia.

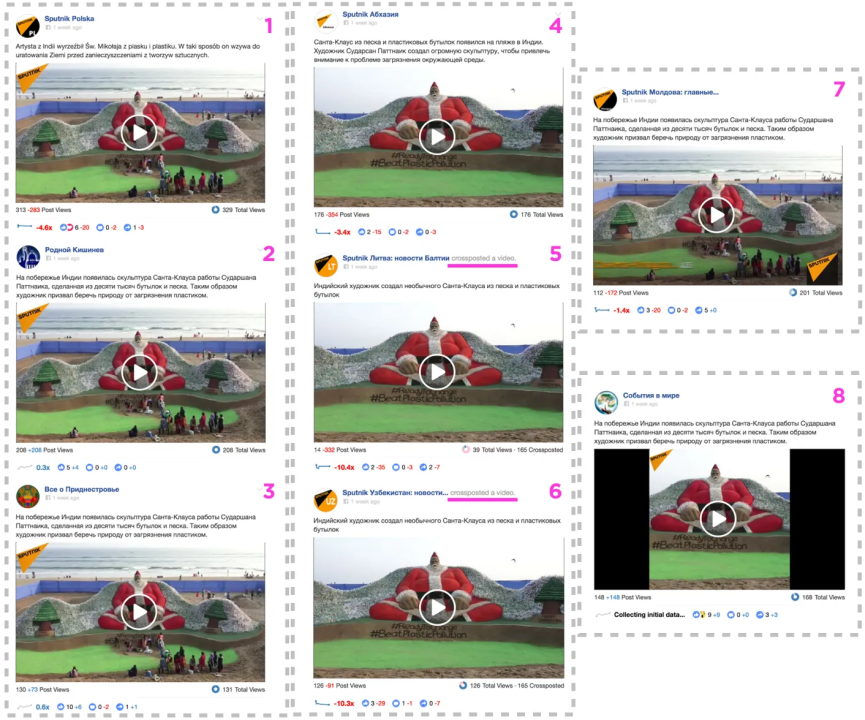

A mix of uploading and cross-posting was also used in the case of a video about a sand sculpture of Santa Claus with plastic bottles in India. @DFRLab identified four different versions of the same video, varying by zoom and dimension ratio.

Overall, the majority of cross-posts across this network shared Sputnik weather reports.

The cross-posts are important less for the content they shared than for the proof they provide that Sputnik must have been aware of the promotion network.

Network in Latvia: Confirmed

The most explicit confirmation of the link between these pages and Rossiya Segodnya came from Latvia.

@DFRLab independently investigated the network in this country before becoming aware of the Facebook investigation, based on the pattern of cross-posting Sputnik weather videos. @DFRLab came to the initial findings together with Latvian investigative TV show De Facto, which tipped @DFRLab about four pages from the network. De Facto interviewed Sputnik Latvia’s Moscow-based Editor-in-Chief, Valentīns Rožencovs, in November.

Rožencovs confirmed that Sputnik was running the pages but said that it was a question of “normal content promotion on social networks” and that Sputnik was “not breaking any rules, neither Facebook’s, Latvia’s, nor Russia’s.”

The interaction confirmed Sputnik’s responsibility for the pages in Latvia.

Rossiya Segodnya Connections

The network in other countries was less explicitly tied to Rossiya Segodnya, but technical and personal indications provided a variety of leads to the Kremlin mouthpiece, beyond the overwhelming amplification these pages gave to Rossiya Segodnya outlets.

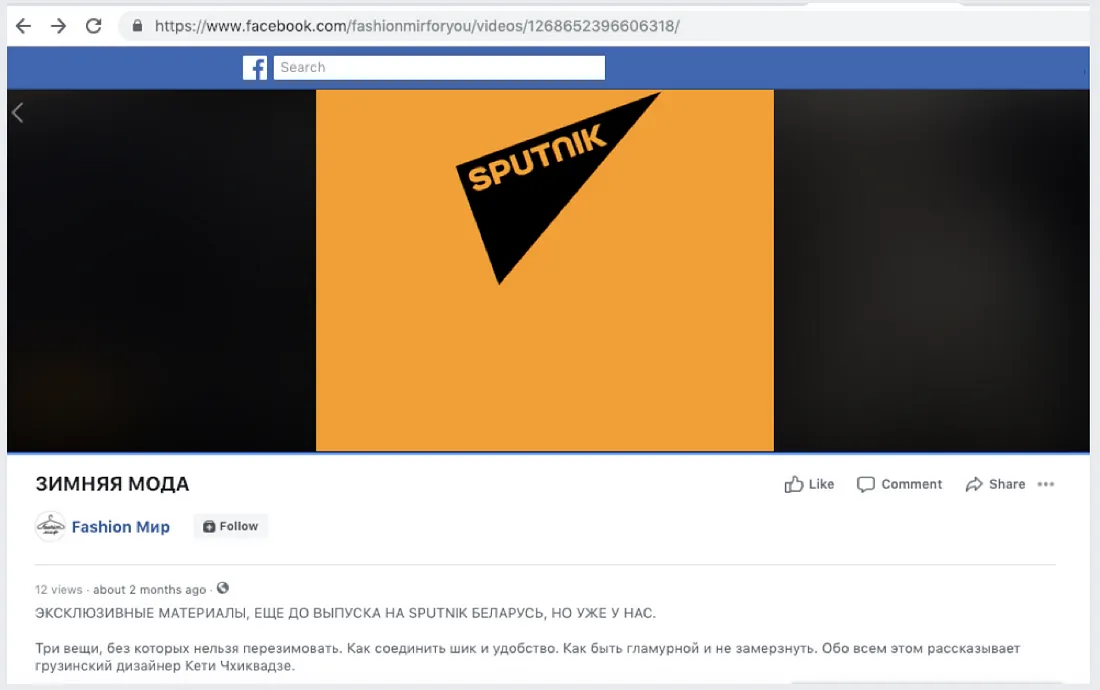

In Belarus, the page @fashionmirforyou posted a Sputnik video that it described as “exclusive material that we’ve already got, before Sputnik Belarus broadcasts it.”

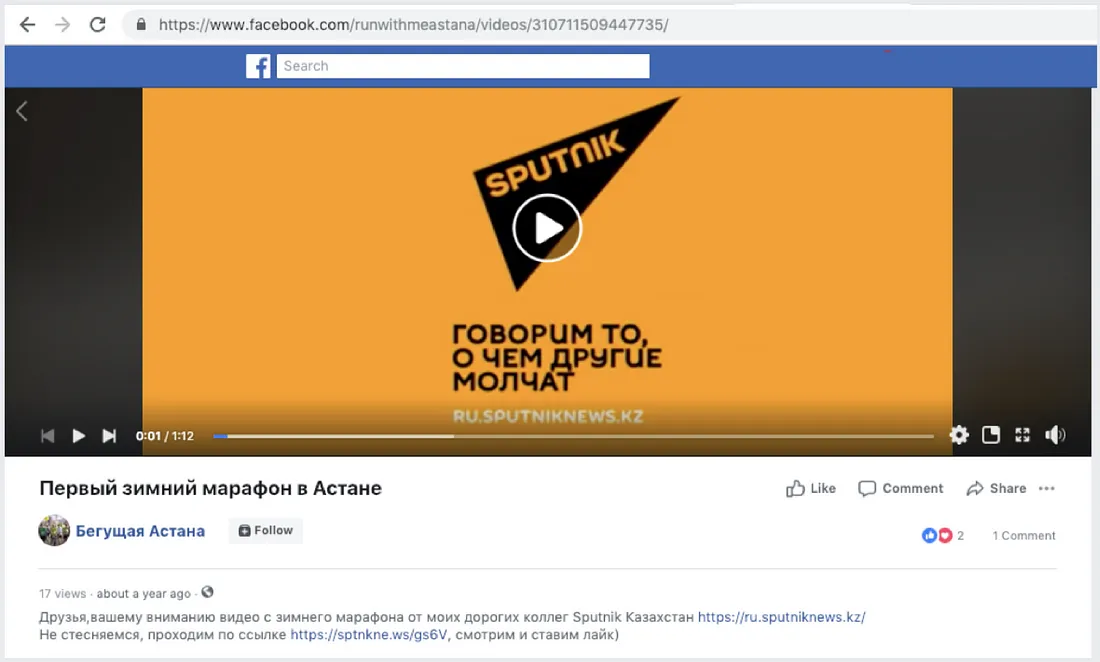

In Kazakhstan, a page dedicated to running in the city of Astana posted a Sputnik video of the city’s winter marathon. The accompanying text, translated from Russian, read: “Friends, for your attention, a video of the winter marathon from my dear colleagues at Sputnik Kazakhstan. https://ru.sputniknews.kz/ Let’s not be shy, let’s go to the link https://sptnke.ws/gs6V, watch and leave a like).”

The post connected the page directly to a Sputnik employee and was the only video the page shared. It only posted six times following its creation in October 2017. Three were apparently authored posts about running, and the other three shared Sputnik content. Promoting Sputnik was one of the two main effects of its posting, but the total number of posts were so low that this should not be considered an effective promoter.

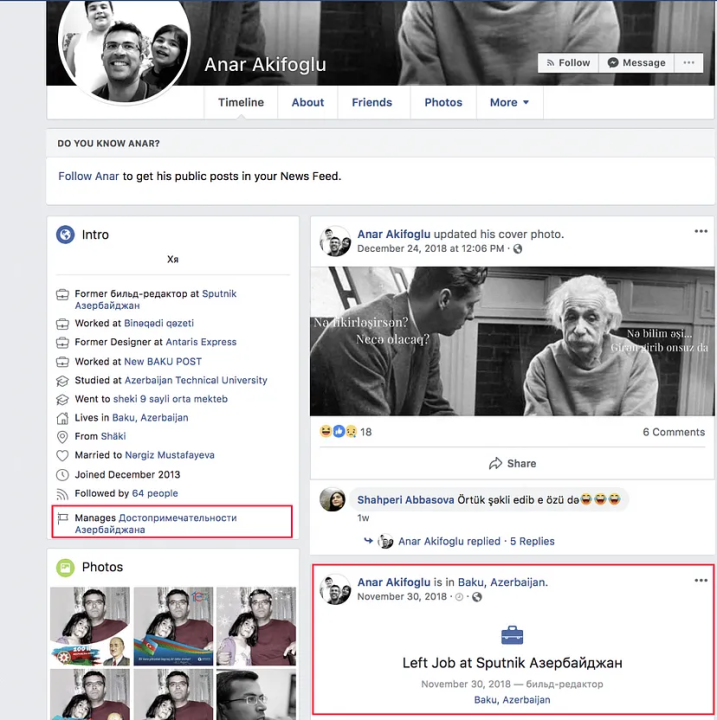

In Azerbaijan, one page was managed by a user called Anar Akifoglu, who listed Sputnik as his employer until the end of November 2018.

In Georgia, one page dedicated to fashion ran a paid ad promoting a Sputnik post, which suggests a financial connection. In Kazakhstan, a page devoted to national pride gave Sputnik’s Kazakhstan service as its web address.

These are not conclusive links, but they reinforce the pattern of connections between Rossiya Segodnya and the international network of pages that promoted its content, independent of Facebook’s internal analysis.

Promoting Sputnik

Overwhelmingly, these pages promoted content from Sputnik. In most cases, the content was in line with the pages’ declared interest, such as food or sports: this therefore appears to have been an attempt to audience build and draw users’ attention to Sputnik as a media brand rather than to manipulate them. Russian political or geopolitical messaging.

Almost all the pages had some Sputnik content; some of the pages had only Sputnik content.

The most obvious example was the above-mentioned page apparently devoted to fashion in Georgia, which paid to promote a Sputnik article about fashion, as in the image below.

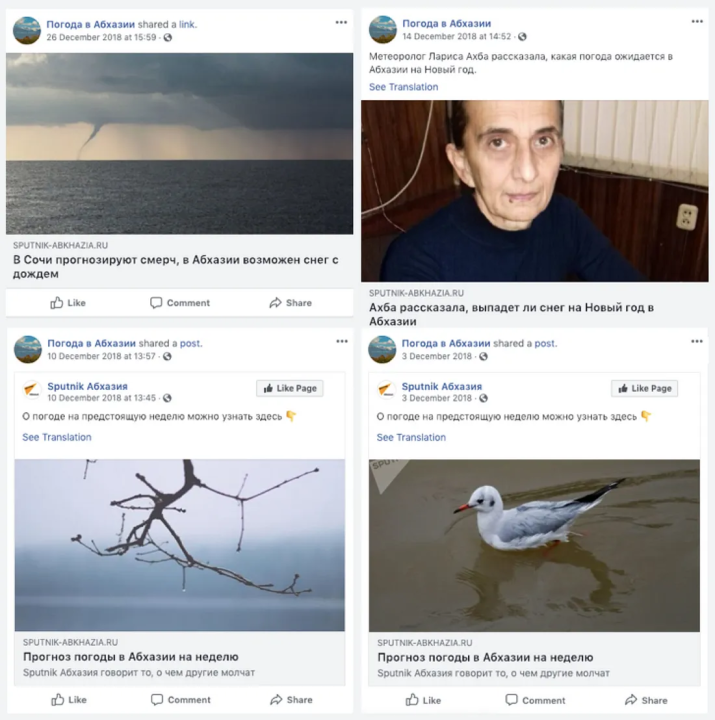

Another page, ostensibly devoted to the weather in the breakaway Georgian region of Abkhazia, exclusively shared content from the Kremlin outlet’s website and Facebook page.

Pages such as this only had one effect: to promote Sputnik’s content, online and from Facebook, to their target audience.

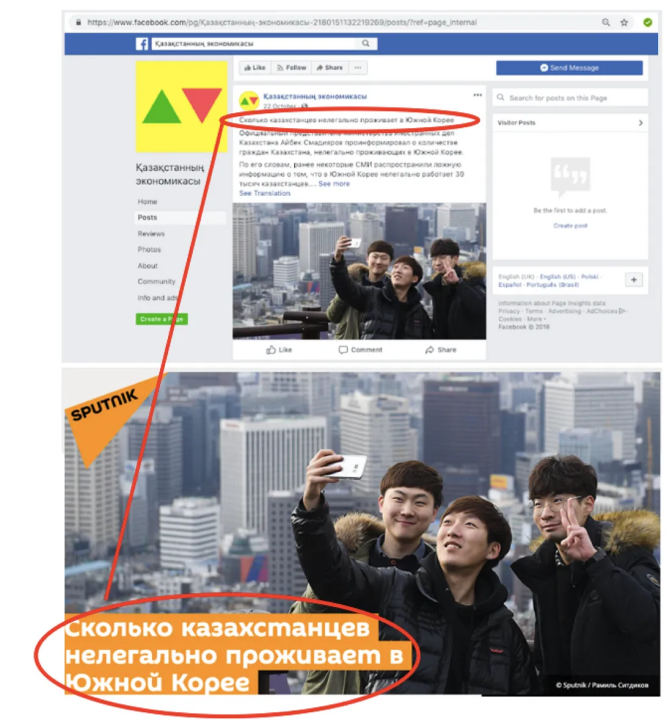

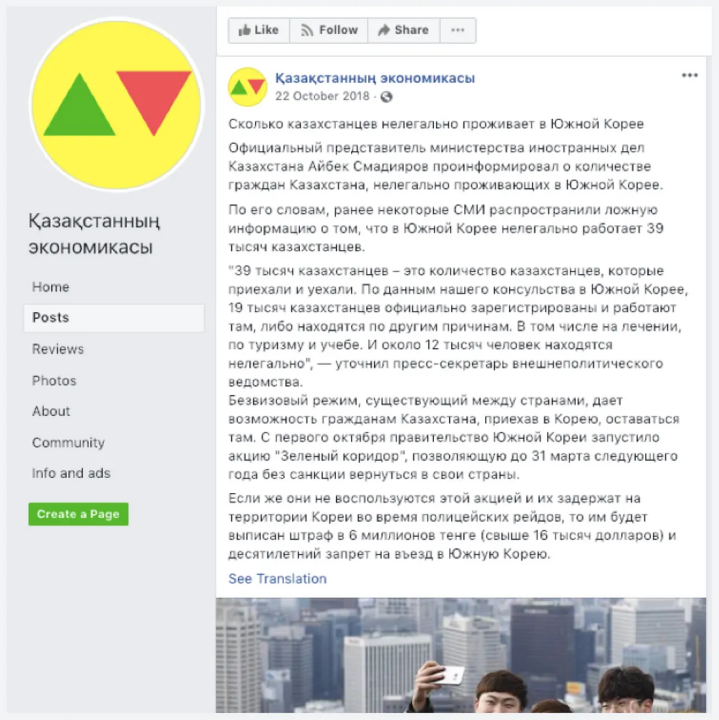

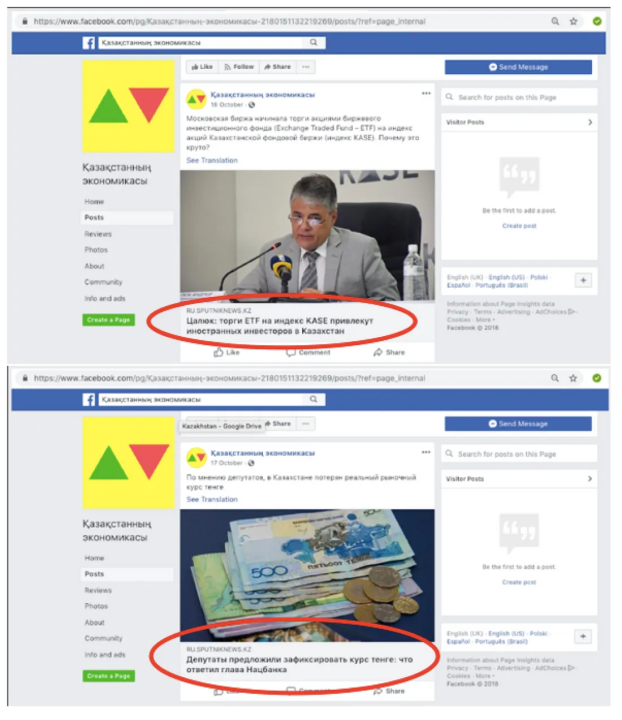

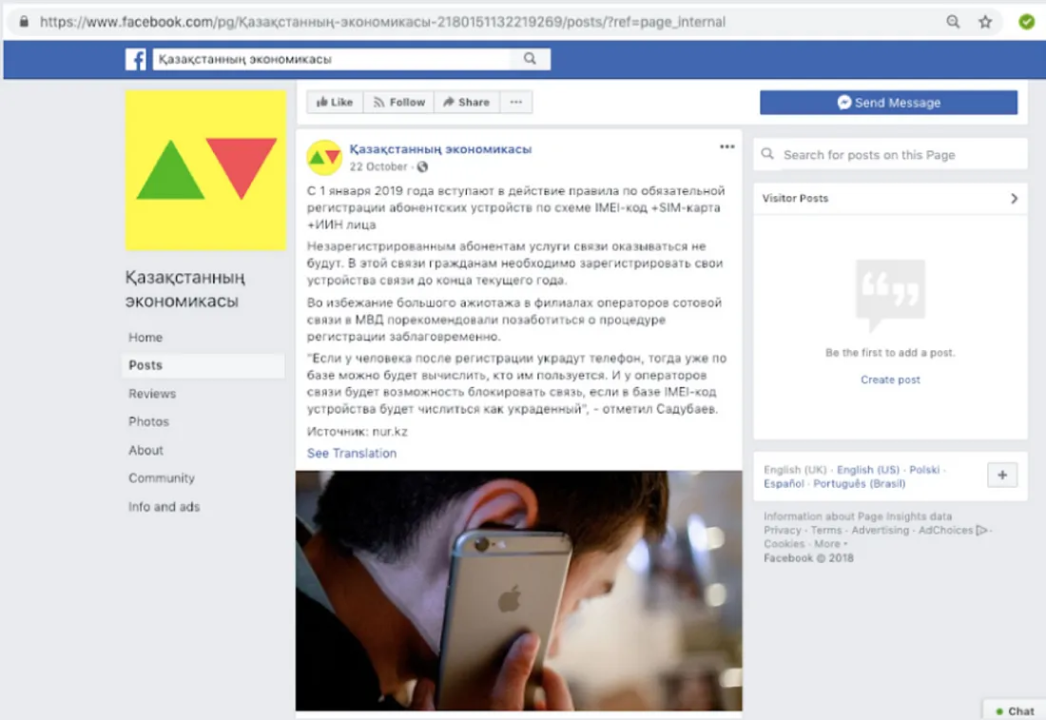

Some of the pages in this category shared Sputnik posts without naming the source. For example, the page in the image below, which ostensibly focused on the economy in Kazakhstan, copied Sputnik stories verbatim but did not attribute it.

The same page interspersed these unattributed posts with overt shares from Sputnik.

It also interspersed them with shares from other sites, which it did attribute.

The effect of this behavior was both to promote Sputnik as a source and to promote its content without naming the source.

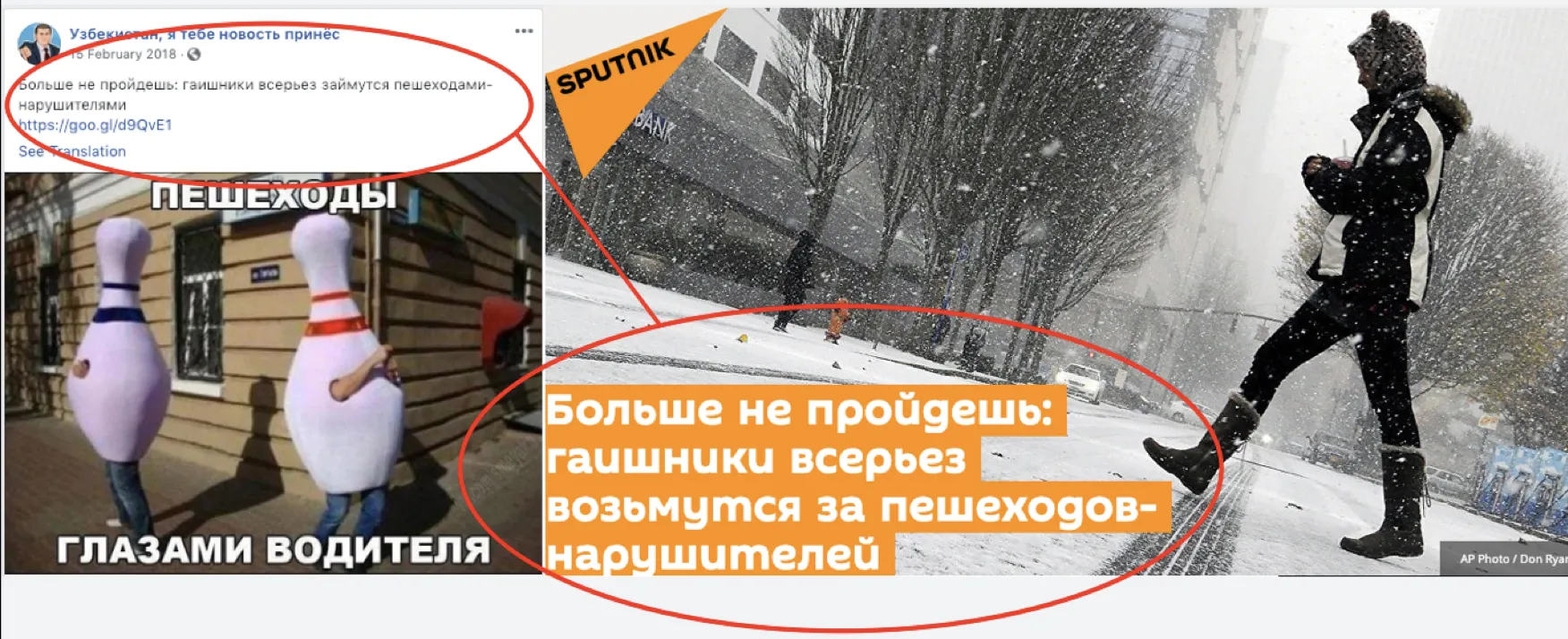

Another page, apparently dedicated to news in Uzbekistan — its name, translated from Russian, is “Uzbekistan, I’ve brought you news” — repeatedly posted Sputnik Uzbekistan articles via Google’s link shortener, together with comic memes. In each case, the text in the post matched the Sputnik headline, and the Google link led to the Sputnik page. This appears to have been an attempt to drive traffic to the Sputnik Uzbekistan website without advertising the source.

This account fell silent in February 2018, suggesting that the attempt was deemed unsuccessful.

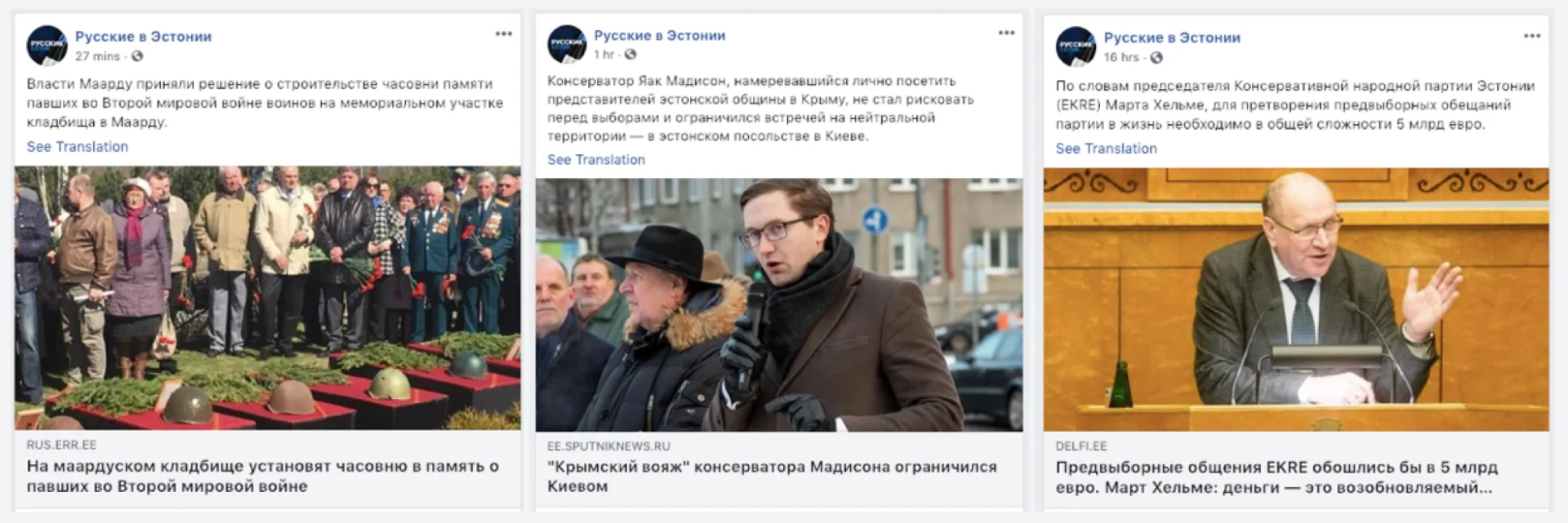

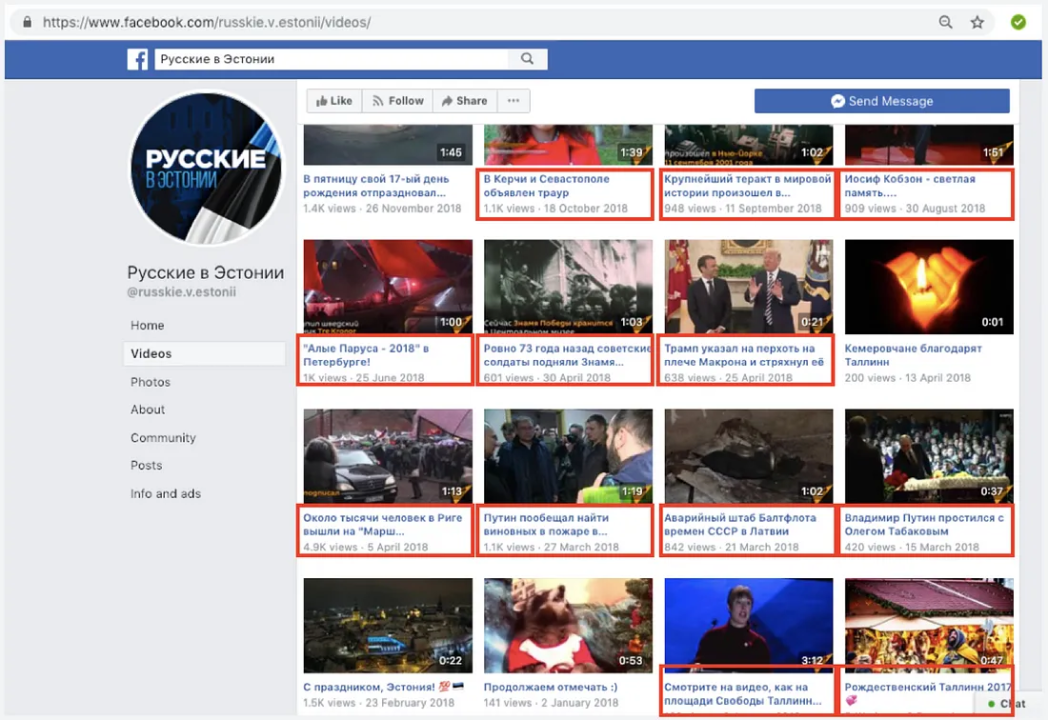

More of the pages interspersed their Sputnik shares with shares from other websites. This was especially the case of the pages based in Estonia, which alternated articles from Sputnik with Russian-language articles from mainstream Estonian outlets ERR.ee (the national broadcaster) and delfi.ee (a popular news portal).

Such pages’ video content, however, showed a strong focus on promoting Sputnik.

Their effect was to promote Sputnik content, especially video, but to also promote content from mainstream channels, thereby giving an appearance of greater independence.

Amplifying TOK

To a lesser extent, the pages also amplified TOK, a video service which is part of the Rossiya Segodnya portfolio, as its website makes clear.

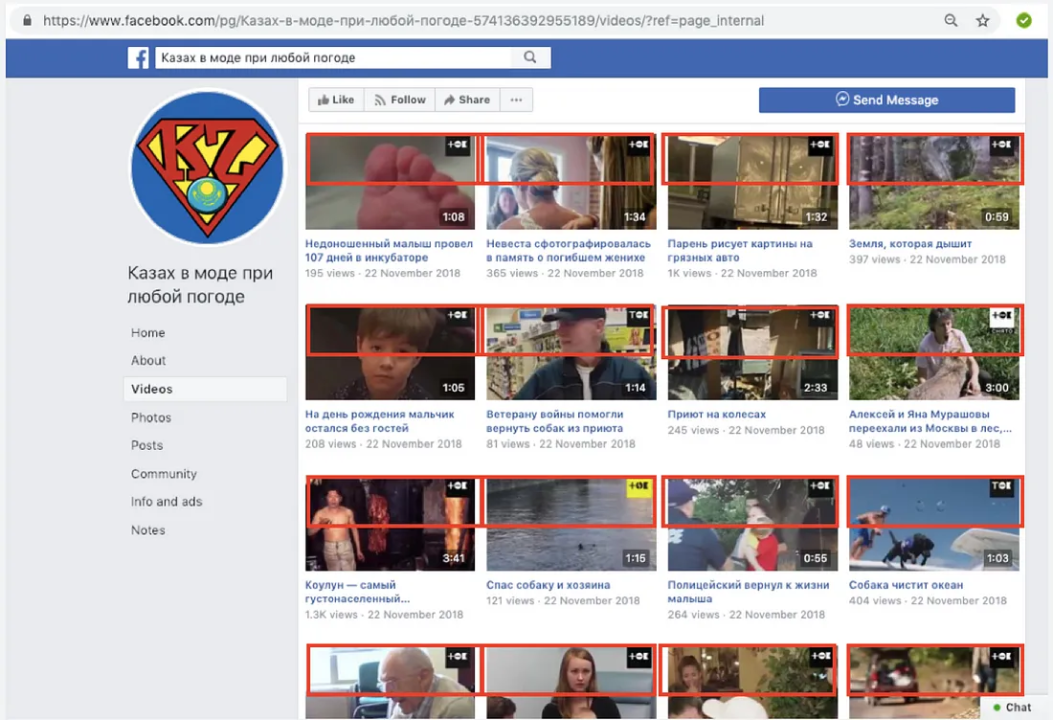

In the most extreme case, one page, @Казах-в-моде-при-любой-погоде (translated from Russian, “Kazakh is fashionable in any weather”), posted 34 TOK videos in a burst on just one day, November 22, 2018.

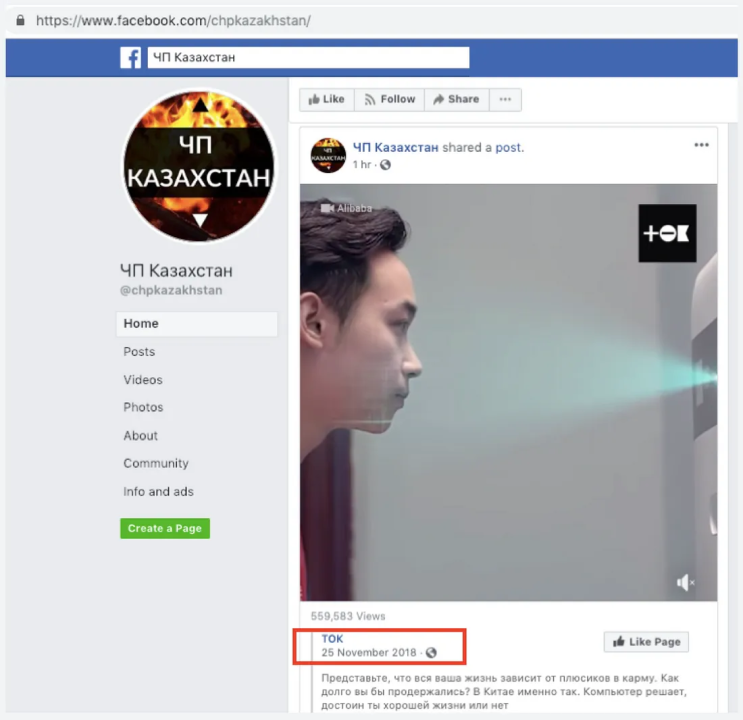

Most of the amplification of TOK was conducted by accounts focused on Kazakhstan. Another booster was @chpkazakhstan, which was dedicated to news events in the country. This page mainly amplified Sputnik videos but also posted shares direct from the TOK Facebook page.

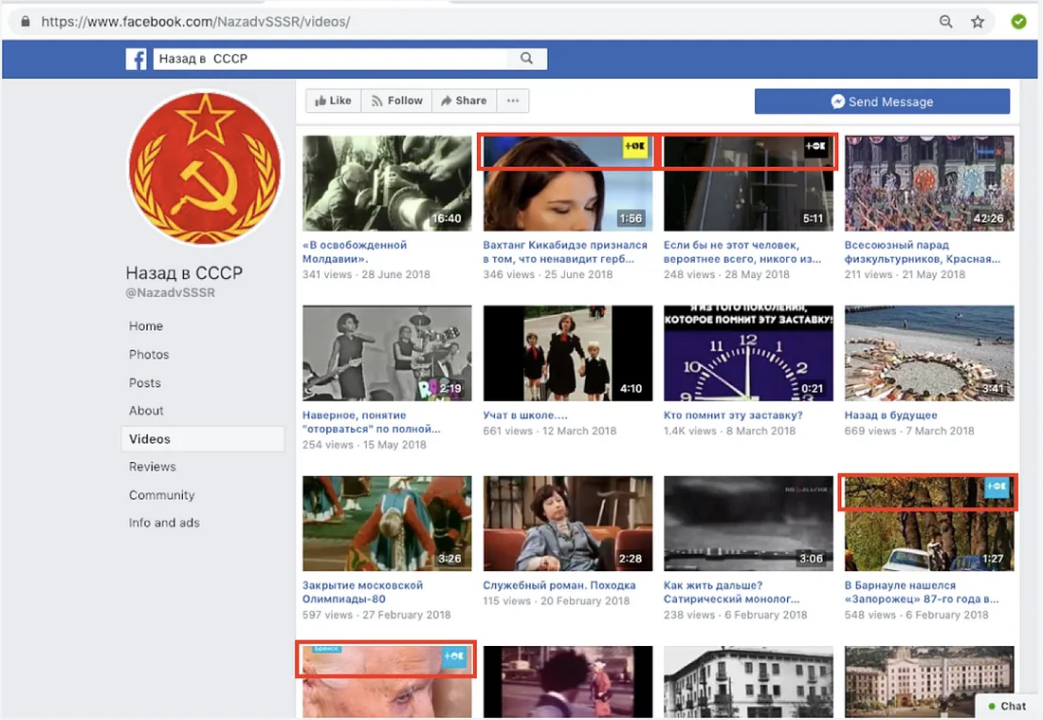

A third booster, @NazadvSSSR (translated from Russian,“Back in the USSR”), did not give a country location but dedicated itself to nostalgia for Soviet times. Its video posts mainly repackaged Soviet TV footage of the 1970s and 1980s interspersed with TOK videos.

Overall, this network posted TOK much less often than Sputnik, but the inclusion is important because it indicates that the network amplified Rossiya Segodnya more broadly, not just Sputnik itself.

Audience

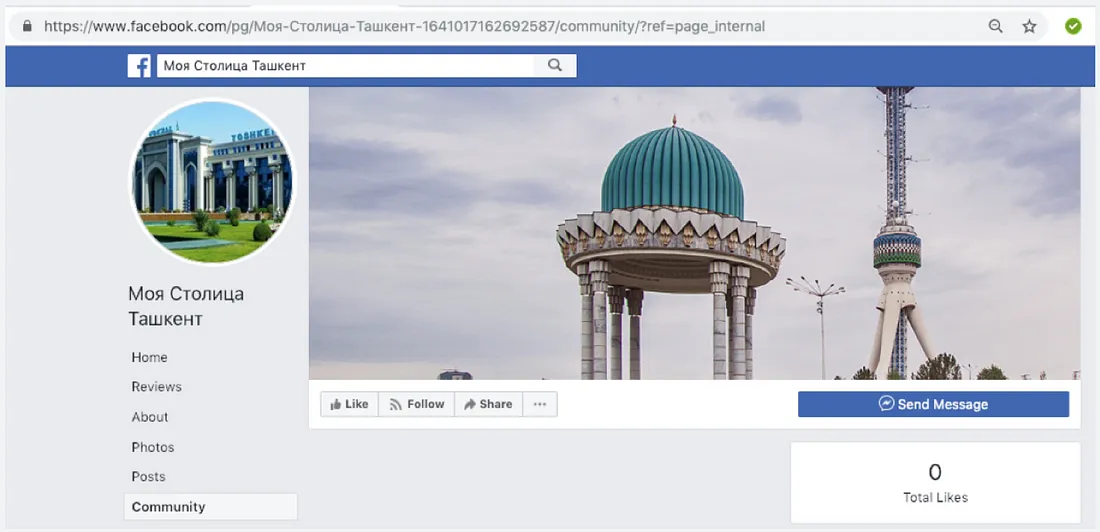

The pages had a very mixed reception online. Some gained almost no followers, and one dedicated to the capital of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, had none at all.

Others, however, had tens of thousands. The pages devoted to the leaders of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Chechnya numbered almost 150,000 followers between them.

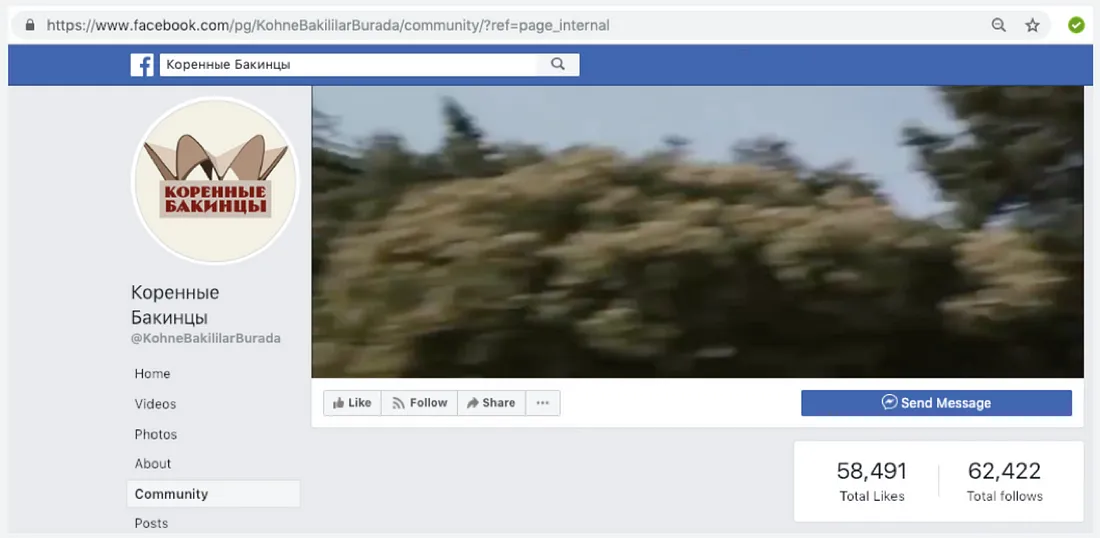

A page devoted to the people of Baku, Azerbaijan, had 62,422 followers.

In total, all the pages together had 853,413 followers, although this number is likely to include an unknown figure of accounts that followed multiple pages. This is 1.7 times higher than the total number of followers (495,947) of all Sputnik’s official pages across the same countries.

Creation Dates

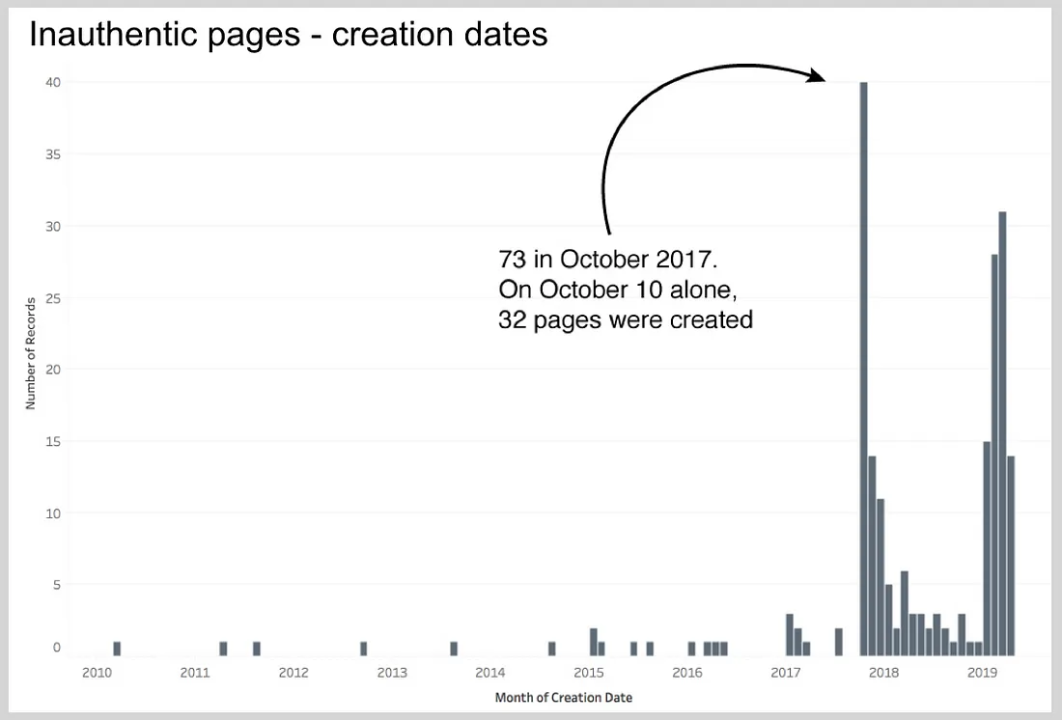

The vast majority of the pages were less than two years old. As we have seen, 73 were created in October 2017; over 50 were created in October-November 2018.

Not all the pages posted all the time, however. Some stopped posting in early 2018, some in late 2018. Others were active right up to the moment of the takedown. This suggests that they were conducting a form of A-B testing, abandoning pages that did not show results.

From Covert to Fraudulent

Most of these pages were covert, rather than overtly fraudulent: they simply gave no information about who was behind them.

In the case of Georgia, however, the evidence suggests that a cluster of nine different pages was run by one fraudulent account. The pages focused on nature, architecture, history, food, and culture, among others.

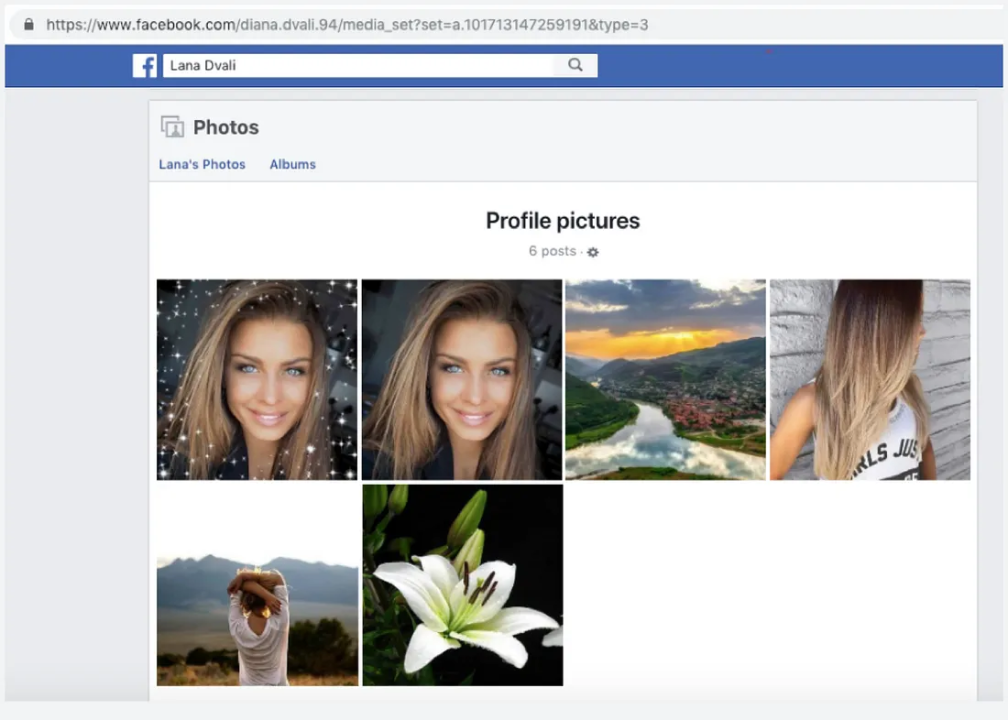

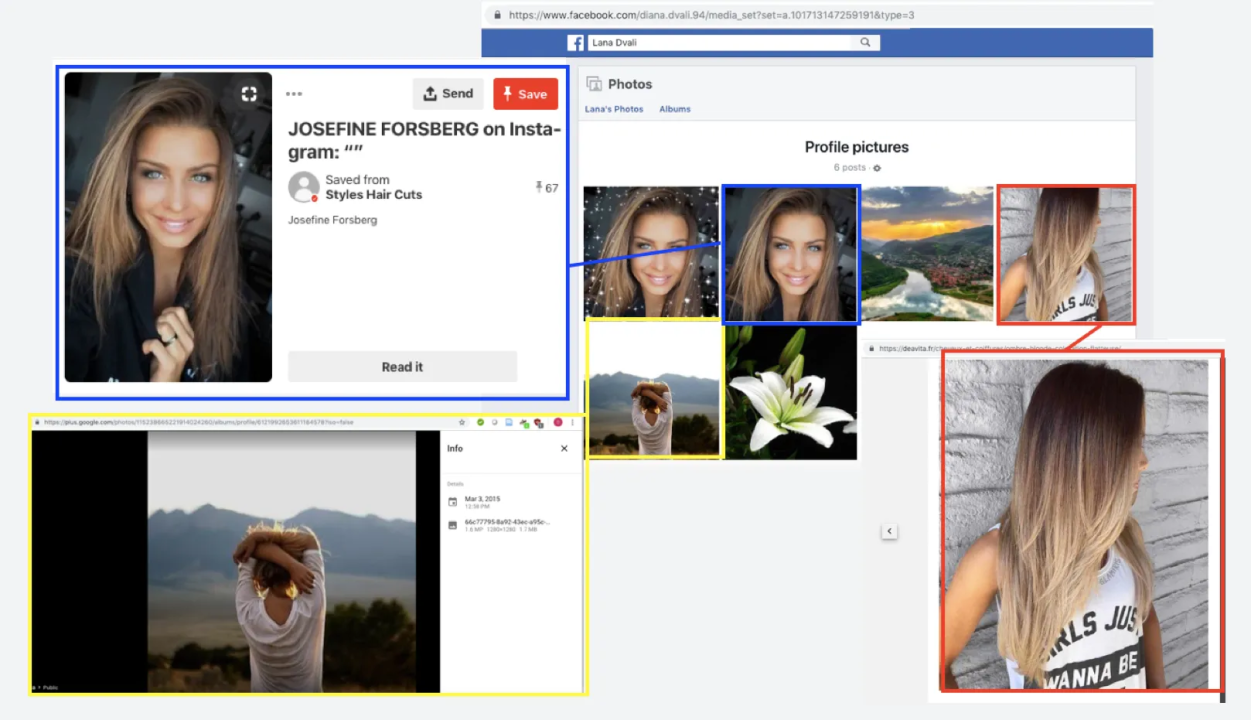

Each page named the same manager: a young woman from Tbilisi named “Lana Dvali,” whose actual Facebook address used the name “Diana Dvali.” The “Lana Dvali” account posted three profile pictures since it was created in October 2017, two of a blonde with her face hidden and the third of a blonde looking at the camera.

All three profile pictures were taken from online sources — one, a French article on hairdressing from July 2017, the second a Google+ profile picture posted in March 2015, and the third taken from Swedish Instagram model Josefine Forsberg, taken from Pinterest.

The Google+ picture is very widely used as a profile picture on Russian social network Odnoklassniki (ok.ru).

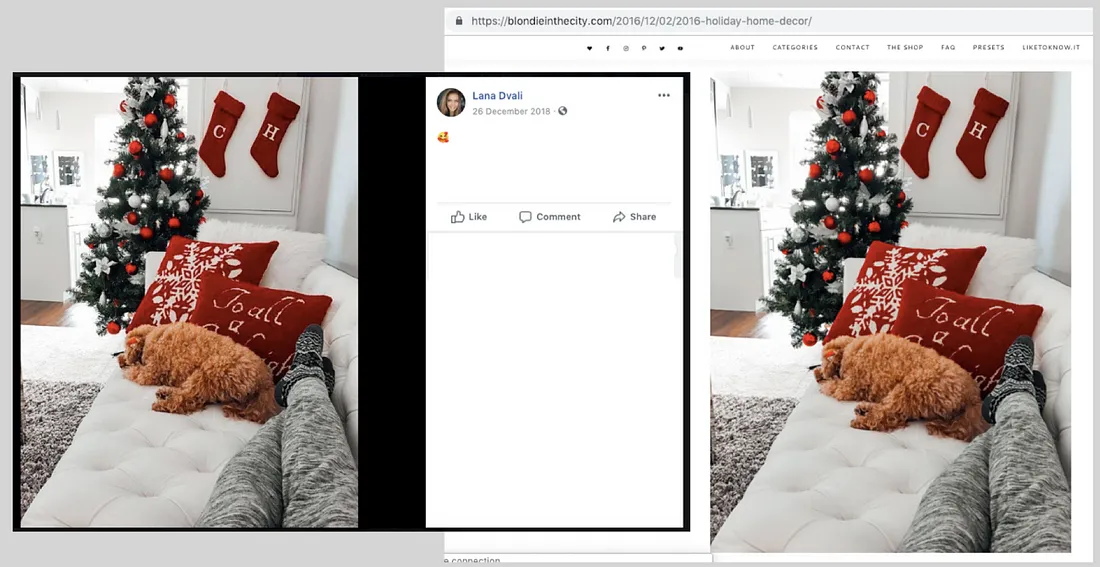

Meanwhile, the “Lana Dvali” account’s Christmas post in 2018 was taken from an image posted by blogger Hayley Larue in 2016.

There is nothing in these posts to suggest that there was a real “Lana Dvali” behind this account. It appears to have been set up as a front to manage the amplification accounts.

Nevertheless, Sputnik Georgia embedded videos attributed four articles to the Facebook page. This, again, suggests a connection between Sputnik and the apparently fraudulent pages.

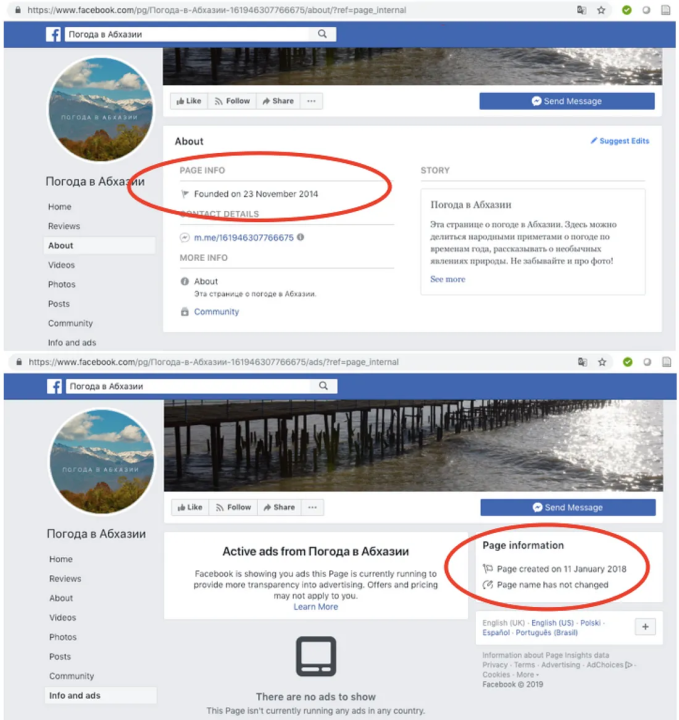

On another occasion, the “About” section of the Abkhazia weather page mentioned above claimed that the page was founded in November 2014, but the “Info and ads” section said it was created in January 2018. The “About” section contains information written by the user; the “Info and ads” section gives automatically generated information.

This suggests an intent to deceive.

Conclusion

Facebook concluded, based on its own data, that this network of pages “used similar tactics by creating networks of accounts to mislead others about who they were and what they were doing.”

Facebook did not share that data with @DFRLab.

The open-source evidence indicates that the primary effect of almost all these pages was to promote Rossiya Segodnya outlets without mentioning any connection with the Kremlin agency.

In Latvia, Sputnik confirmed that it was running the pages as a “promotion” technique. Elsewhere, a range of open-source evidence, including cross-posting, user statements, and details of page managers, provided indicative links to Rossiya Segodnya and its employees.

The overall effect of the network was to provide Sputnik, in particular, with an audience significantly bigger than its own organic one. This was a covert promotion operation, and Rossiya Segodnya outlets were the main beneficiaries.

[This piece was updated to say that “Facebook did not share that data with @DFRLab” instead of “Facebook did not share that data with Facebook,” as originally written.]