Crowdsourcing Violence in Kashmir, Part 2

How terror groups in the Kashmir Valley use Burhan Wani’s model to fuel a new wave of homegrown insurgents via social media

Crowdsourcing Violence in Kashmir, Part 2

BANNER: (Source: @Dfrkaul/DFRLab via Stocknap.io and Bannersnack)

This is the second article in a two-part series examining the use of social media to attract popular support for the insurgency in Kashmir. Part 1 discussed militant leader Burhan Wani’s pioneering strategy; Part 2 discusses other terror groups’ refinement of his model.

Kashmiri militant Burhan Wani’s adept use of social media platforms paved the way for other Kashmiri separatist groups and militants who began to follow his example by sharing engagement-ready content with a large segment of the population.

Aside from the dissemination of propaganda, terrorist organizations (such as Wani’s Hizbul Mujahidin) are also increasingly using social media platforms to coordinate with local supporters. This development has blurred the line between civilian and insurgent, thereby complicating counterterrorism efforts in the state.

Refining Wani’s Model for Insurgency

Since Wani’s death in July 2016 at the hands of Indian security forces, terrorist and militant organizations in the Kashmir Valley have refined the “freedom fighter” narrative initially popularized by Wani to attract average Kashmiri youth online to the insurgency. Subsequently, a majority of the militant groups operating in the valley have set up dedicated messaging groups on WhatsApp, Facebook, and Telegram to amplify their narrative and communicate instantaneously with a growing user base of Kashmiris on these platforms.

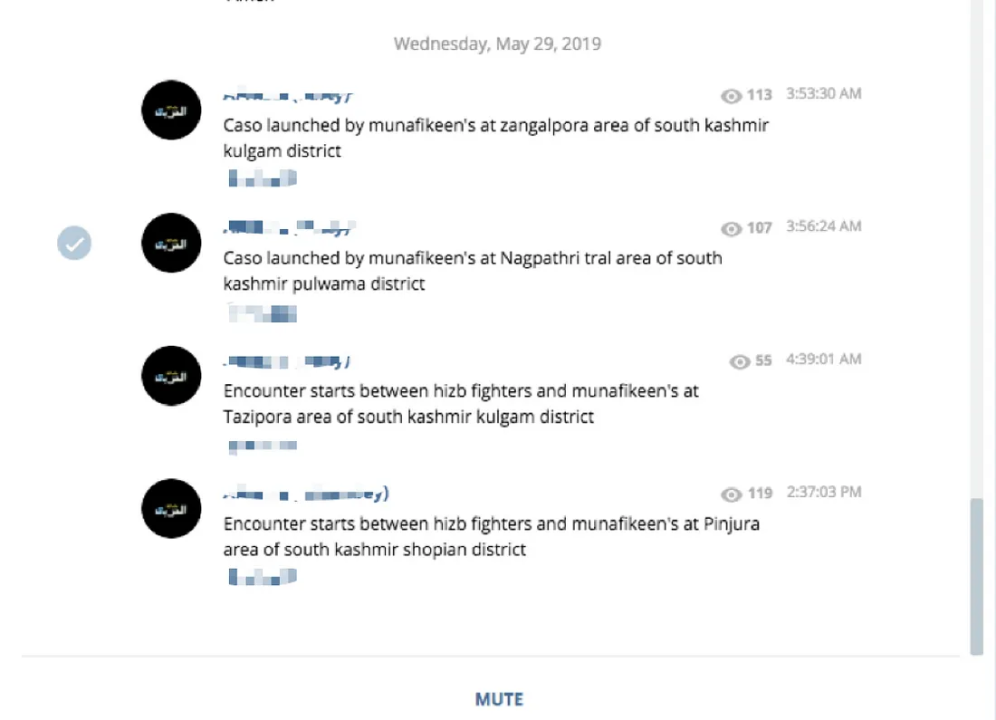

In addition to spreading broad anti-India narratives to radicalize the youth, militants also use social media platforms to relay information in real time, calling for their supporters to coordinate protests and disrupt ongoing security operations.

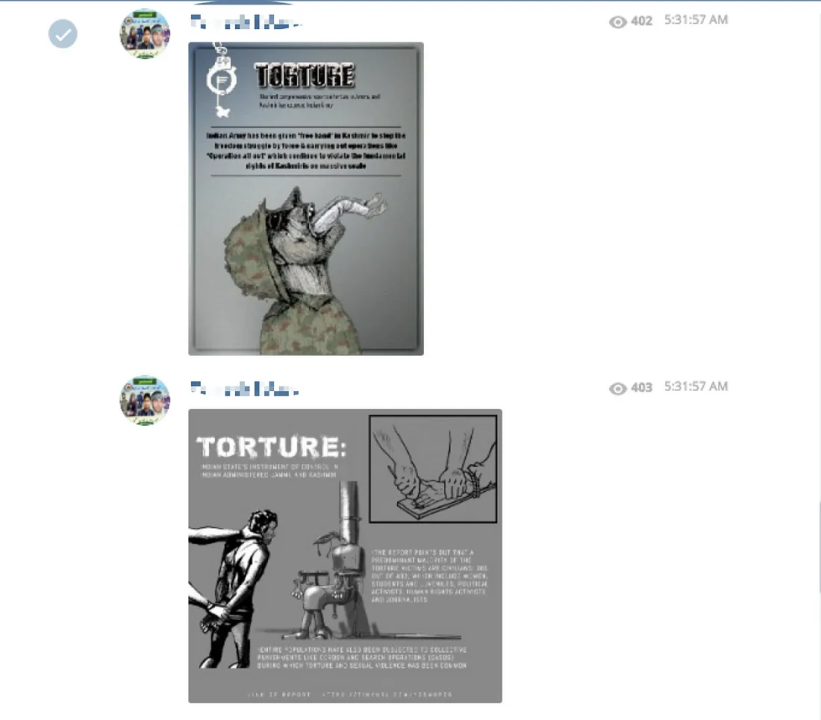

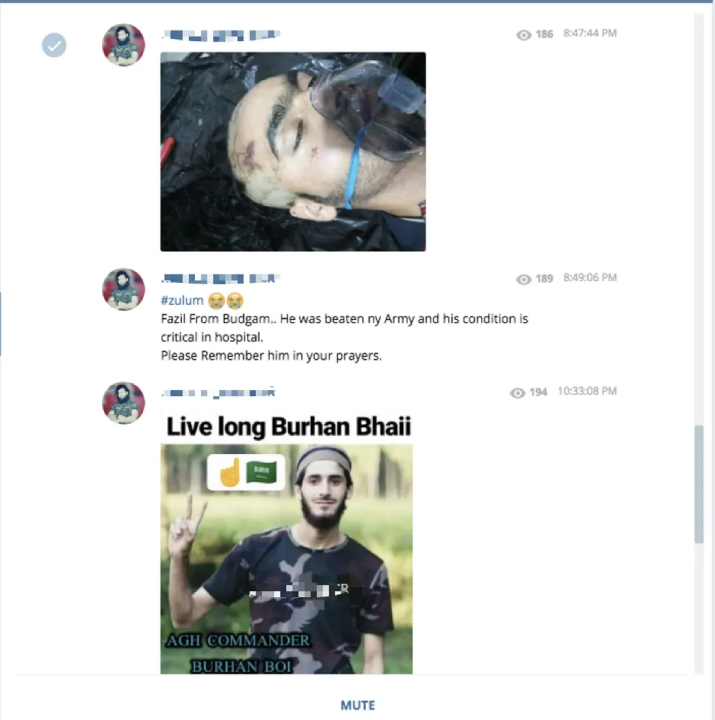

The Telegram channels and Facebook groups used by these groups and their supporters upload posts and stories showing alleged victims of police and military brutality in the valley. These posts attempt to portray civilian casualties and the killing of terrorists as a form of deliberate cruelty inflicted by the Indian state upon its victims. Those taking up arms against Indian security forces are characterized as fighting for the rights of the local population.

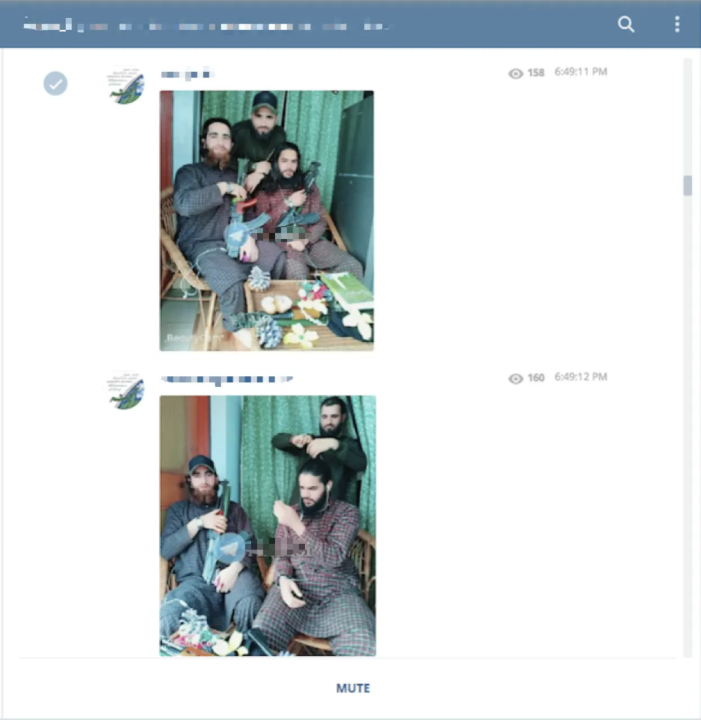

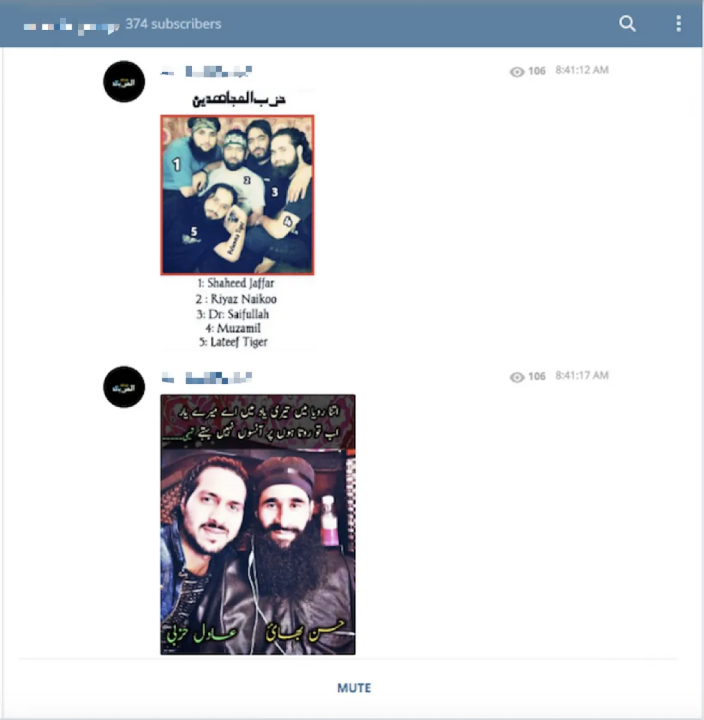

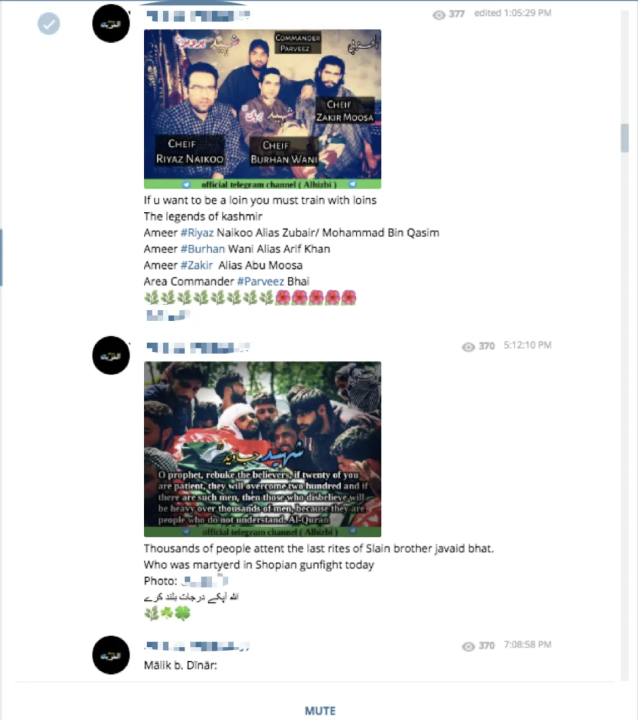

By uploading photos and videos on Facebook and WhatsApp that showed him and his fellow militants’ faces, Wani attempted to humanize the militants in the eyes of their audience. Other groups in the valley now routinely replicate this tactic in their Telegram channels, posting photos of current insurgents enjoying their lives and bonding with one another.

These photos bring a degree of relatability to the militants in the eyes of possible recruits. The use of Telegram channels in this manner has also allowed terrorists to communicate directly with prospective recruits.

These Telegram channels also posted content that glorified the insurgency as a pathway to celebrity. Members of these groups shared photographs of slain separatists, as well as of the crowds at their funerals, to suggest to possible recruits that they could attain fame and glory as well, even after their death.

Burhan’s Style of “Freedom Fighters”

The Burhan Wani model of social media insurgency allowed insurgents to gain widespread popularity among the local population of the valley. By using these platforms to further a narrative that highlighted alleged human rights abuses by the security forces while simultaneously framing terrorist and militant groups as “freedom fighters,” Wani helped to normalize the violent aspects of the insurgency in the eyes of the wider population.

This development in turn promoted a growing legitimization of the insurgency within the educated classes and civil society of the valley. This trend is further reinforced by an investigation into sources of radicalization by police services. A study undertaken by the Kashmir police in 2015 examined the cases of 111 local Kashmiri youth who had joined the militant movement. Out of the 111 subjects (88 of which were between the ages of 15–30), 58 eventually returned home. According to the study, of the total subjects investigated by the police, more than 50 percent had been radicalized via consumption of terrorist propaganda disseminated over the internet. Once again, given the source of this study and the polarized nature of the narratives surrounding the conflict, this information should be read with some skepticism.

The upward trend in radicalization shows no sign of abating: as local media outlet The Economic Times recently reported, since March 2019, at least 50 young Kashmiri men have joined the insurgency.

An investigation conducted by India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA) identified 117 suspects who were using 79 WhatsApp groups containing a combined audience of 6,386 phone numbers to crowdsource local members of the public for stone-pelting Indian security forces at civilian protests.

Similarly, in 2017, Indian media outlet NDTV reported that more than 300 similar groups on WhatsApp had served as crowdsourcing channels for the purposes of hindering anti-terror operations in the state. In this manner, social media serves as a vehicle for Kashmiri civilians to play a direct role in active terror operations, which complicates the job of Indian security services.

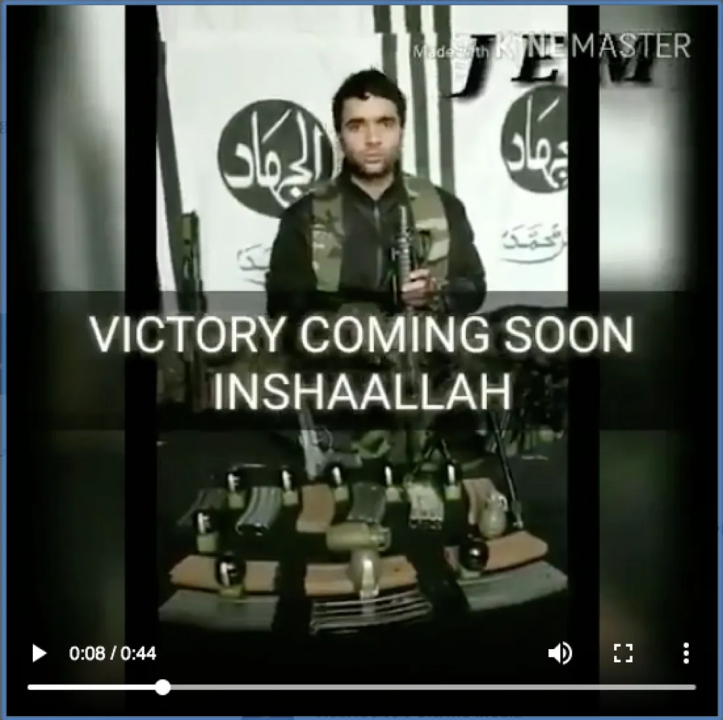

Copycat Terror

In February 2019, Adil Dar, a 20-year-old local of South Kashmir and member of the banned terror group Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), drove a vehicle laden with explosives into an army convoy traveling through the Pulwama district of South Kashmir. The suicide attack, the deadliest in the last three decades of the insurgency, resulted in the death of 40 Indian paramilitary personnel. Dar uploaded content on social media under the moniker Waqas Commando right up until the terror attack. Prior to staging the bombing, he uploaded a video in which he pleaded with local youth, as Burhan Wani had done earlier, to “wage jihad against India.”

Taking the connection a step further, Indian media outlet The Economic Times also reported that in 2016, Dar had suffered a gunshot wound to the leg from security forces when participating in protests incited by the killing of Wani. The article also noted that Dar’s parents later claimed that Wani’s death was the pivotal event that lead their son to take up arms against the state.

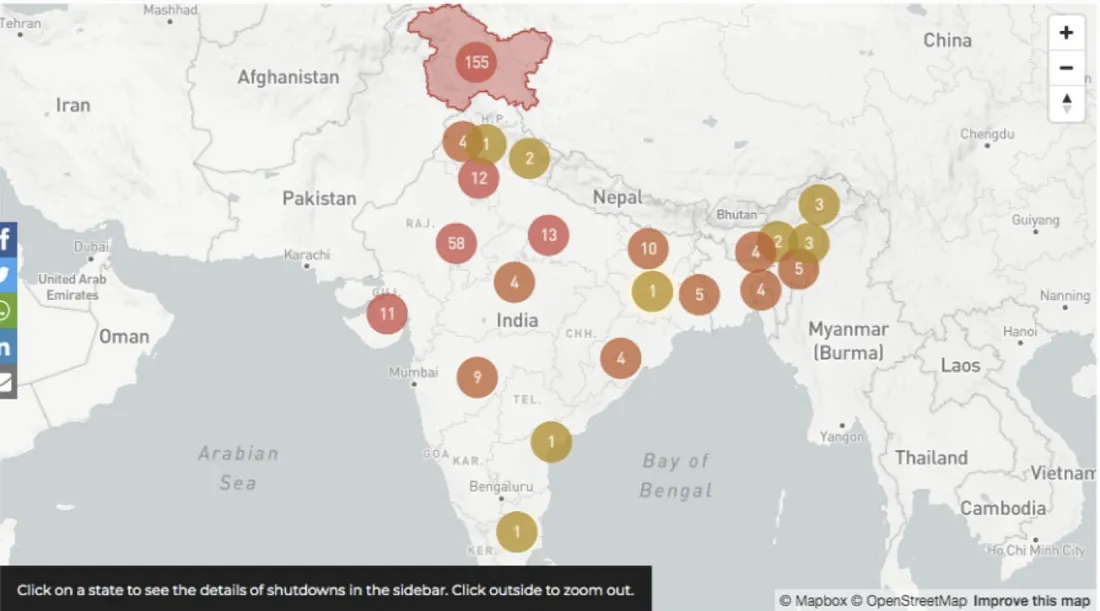

Internet Shutdowns: A Short-Term Response

Given the pervasive nature of terrorist propaganda on social media platforms, the Indian government has taken drastic steps to curtail the amplification of such content. According to open-source data compiled by the India Internet Shutdown, an information portal run by the Software Freedom Law Centre in India, there have been 155 instances of a government blackouts of internet and mobile data services in Jammu and Kashmir since 2012.

Despite these efforts, Kashmiri researchers note that members of the terror groups have simply shifted to more secure platforms and the use of VoIP and VPNs to bypass these security measures and retain access to their contacts.

Internet blackouts cannot effectively combat this growing threat. Bereft of a systematic approach toward monitoring and countering the narratives furthered by terrorist propaganda, such groups will continue to gain support in the valley. As Khalid Shah, an associate researcher on Kashmir at the Observer Research Foundation, noted in an article published in the wake of the Pulwama bombing: until the Indian government implements an effective counternarrative, it cannot capture the “mind space” that fuels terrorism.

The DFRLab will continue to monitor the information environment in India, with an emphasis on issues at the intersection of national security, technology, and social media.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.