“Gavrilov’s Night”: Multiple Facebook Pages Target Protests in Georgia

Georgian Facebook pages spread coordinated narratives to discredit demonstrators

“Gavrilov’s Night”: Multiple Facebook Pages Target Protests in Georgia

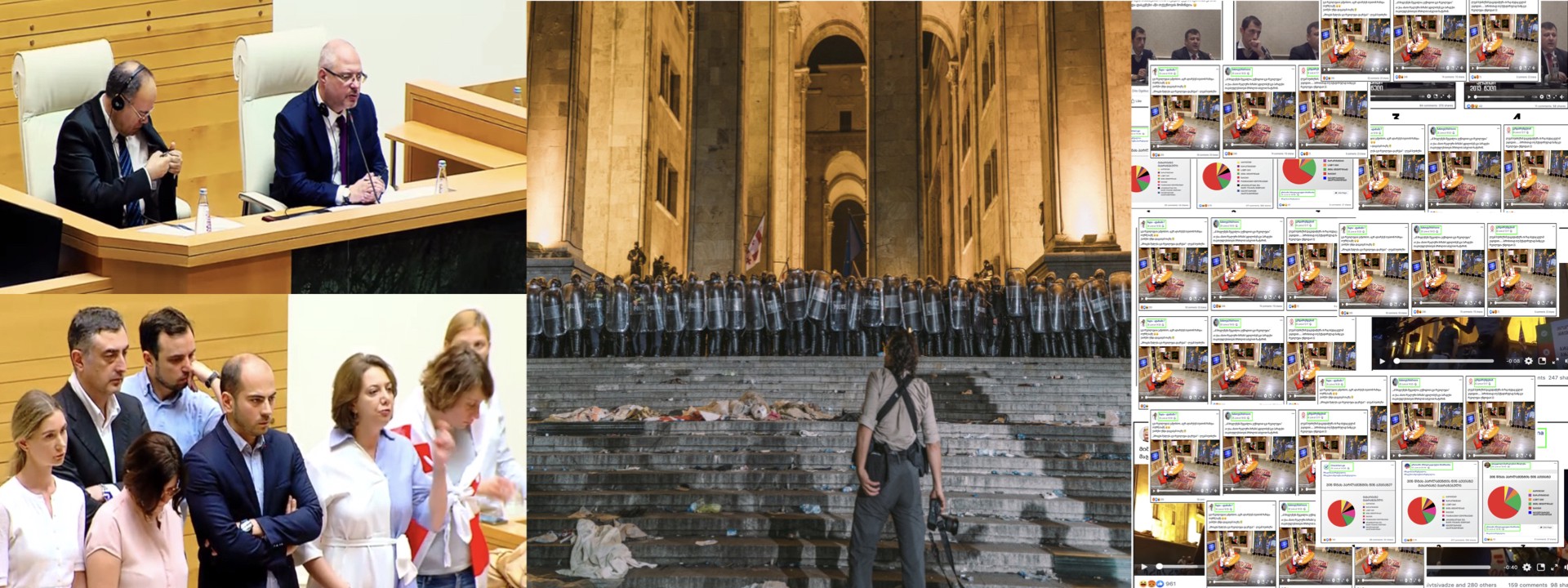

BANNER: (Source: Tabula.ge; ExpressNews; Tbel Abuseridze; Facebook)

For the people of Tbilisi, Georgia, June 20, 2019, will go down in history as “Gavrilov’s Night.”

Sergei Gavrilov, a member of the Russian Parliament closely associated with the Kremlin and the Russian Orthodox Church, paid a visit to the Georgian Parliament. While there, he addressed Georgian lawmakers from the speaker’s chair, which many Georgians saw as an affront to the nation’s sovereignty and triggered days of protest in Tbilisi. Many citizens saw the move to allow him to speak as implied support from the Georgian Parliament for his message.

As protesters flooded the streets, the government responded with a violent crackdown, using tear gas and rubber bullets against the thousands of people assembled. In response to the crackdown, the demonstrators demanded the resignation of Giorgi Gakharia, the country’s interior minister.

The event was set against the backdrop of conflict between Georgia and Russia. In August 2008, the two countries fought a five-day war over Georgia’s two breakaway regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. To this day, the Russian military illegally occupies 20 percent of Georgia’s territory. The Kremlin recognizes Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states, and Gavrilov himself has publicly echoed the Kremlin’s position.

Social media plays an important role in Georgian political and social life, and the number of protests organized via Facebook, including the Gavrilov protest, demonstrate that importance. On social media, a number of Georgian pages spread photos, videos, and statistics aimed at discrediting the protests and its participants.

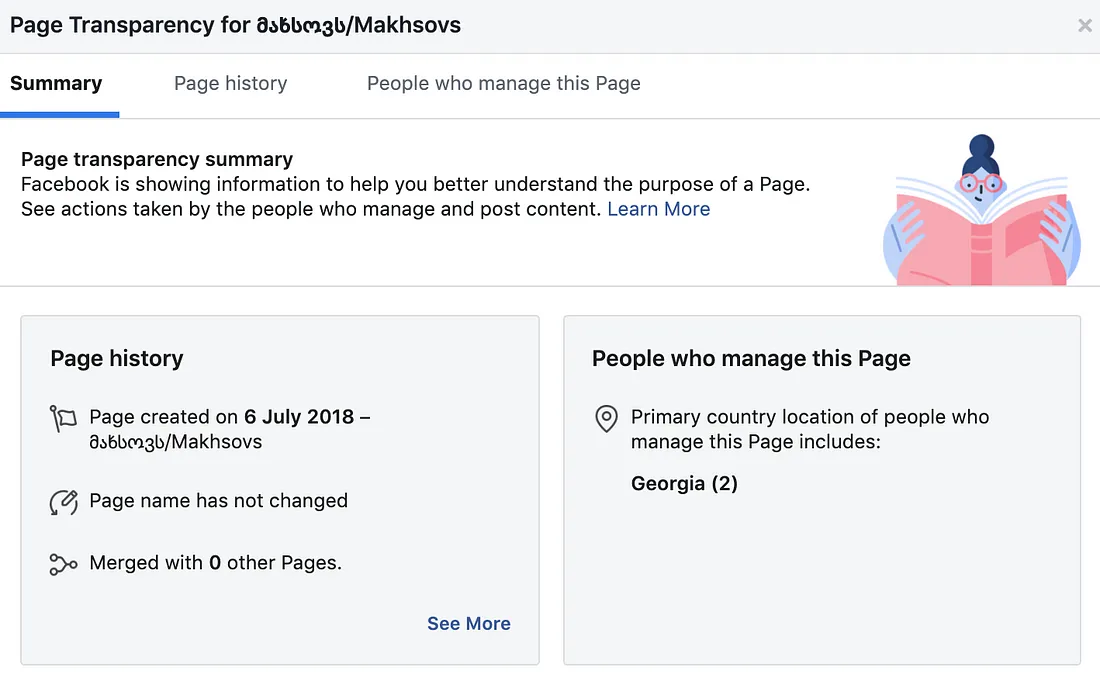

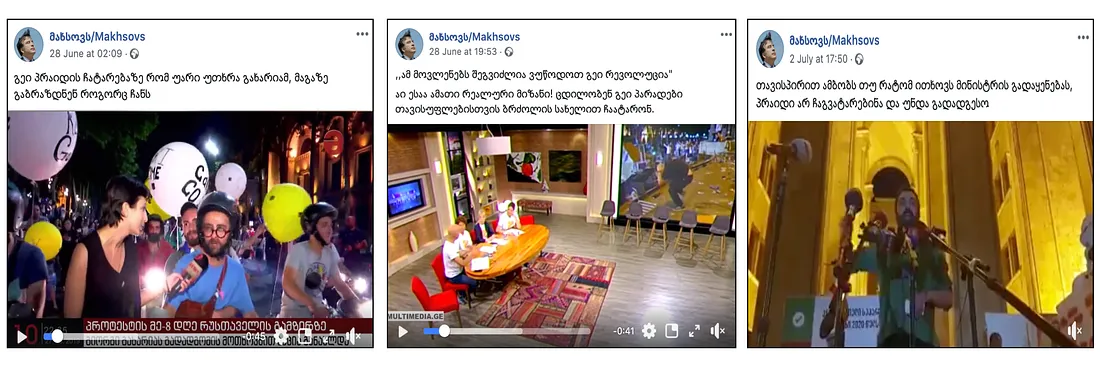

The DFRLab examined one such Facebook page, “მახსოვს/Makhsovs” (translated from Georgian: “I Remember”). The page name was likely a reference to the prior Georgian government’s rule from 2003–2012, which the current ruling party refers to as the “bloody nine years.”

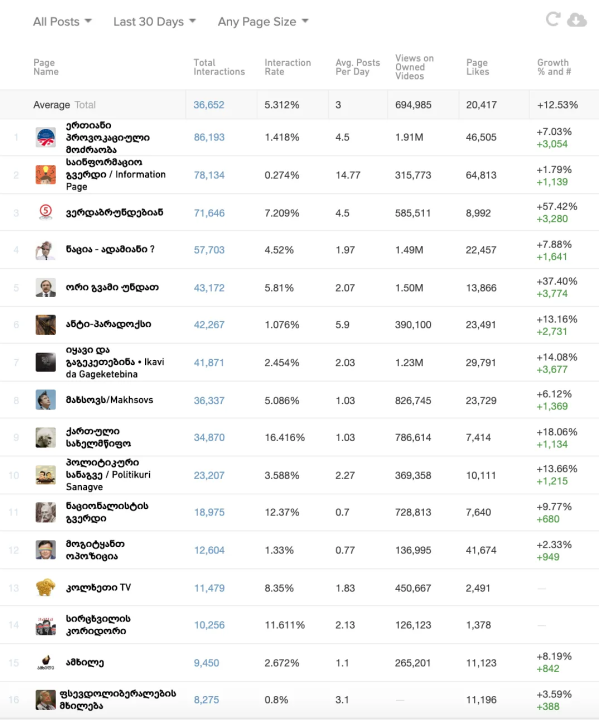

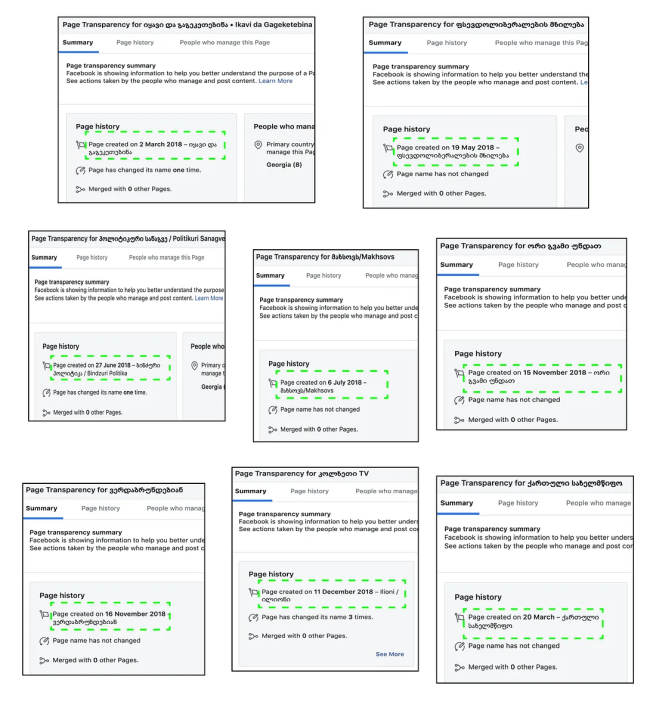

The DFRLab identified 15 additional pages spreading the same narratives to those propagated by I Remember. Similarities in content and posting pattern across these pages indicated coordinated partisan messaging operation, but one that was most likely not inauthentic.

The “I Remember” Facebook Page

I Remember was created in 2018, as were the other pages the DFRLab studied. At the time of analysis, the page had garnered over 27,000 followers and over 24,000 likes.

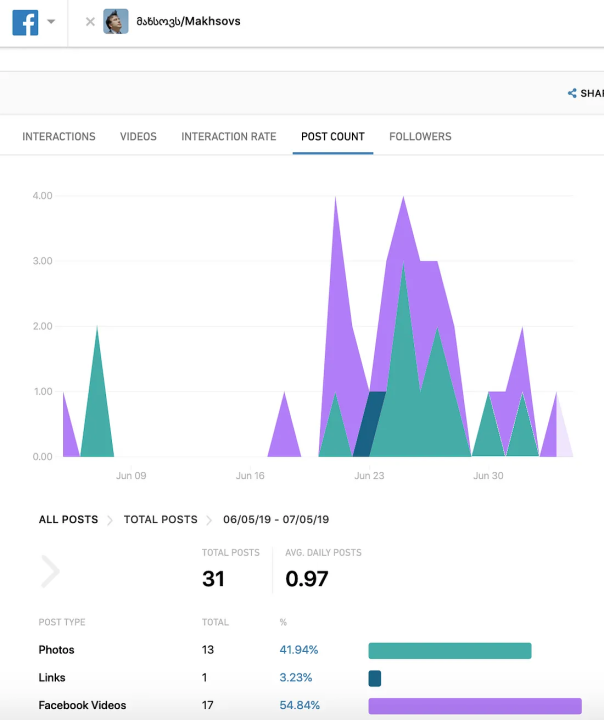

The DFRLab analyzed activity and engagement on the page from June 5, 2019, to July 4, 2019. I Remember peaked — both in posting and engagement — on June 20–21, which correlated with the peak of the protests. Engagement remained high in the protest aftermath.

The Facebook page deliberately minimized the core issues at the heart of the Tbilisi protests: Russia’s continuing occupation of Georgian territories and the overtones of Gavrilov’s visit to Parliament. The DFRLab identified two related, but distinct, narratives spread on the page: the first tied the protests to Georgian opposition leaders; the second tied them to LGBT activists in the country. In the framework of the 4 Ds of Disinformation, the page used the opposition as a pretext for attack (“dismiss”) and pivoted the narrative away from the underlying cause of the demonstrations to attack Georgian LGBT activists (“distract”).

Tying the Protests to Georgia’s Opposition Parties

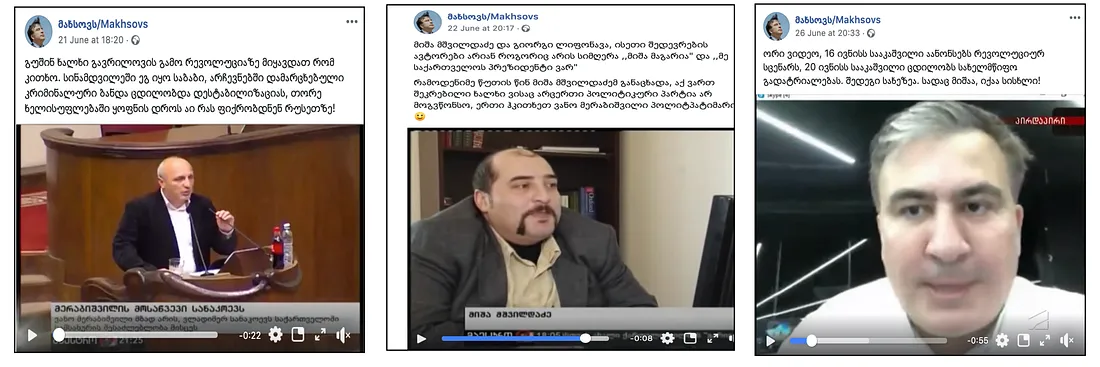

Following the government’s violent crackdown, the page portrayed the demonstrations as rallies orchestrated by Georgia’s opposition parties.

Numerous posts spread a similar and mutually reinforcing message: the protests were a guise by Georgia’s opposition parties to conduct a coup and destabilize the country. A similar narrative came from the Georgian government, including the Prime Minister of Georgia Mamuka Bakhtadze, as well as the Prosecutor-General’s Office.

Tying the Protests to LGBT Activists

In addition to characterizing the protests as organized by Georgian opposition leaders, the I Remember page tied the demonstration to LGBT activist groups and the Tbilisi Pride Festival, which was planned to take place from June 18–23. On June 21, however, the organizers of Pride stated they temporarily postponed the events — the Pride Festival organizers predicted their participants would be targeted by the pro-Russia counter-protestors.

Conflating the two events, I Remember claimed that the demonstrators were Georgian LGBT activists who wanted to conduct LGBT pride events in the country. These claims were likely attempts to damage the protest’s legitimacy, as Georgia is a socially conservative country in which LGBT individuals still face rampant homophobia and discrimination.

Similar Content Across Other Facebook Pages

In addition to the I Remember page, the DFRLab identified 15 other pages that prominently featured one, or both, of these narratives. DFRLab’s CrowdTangle analysis showed that the total page likes across these pages increased significantly during the observed period. Combined, the 16 pages achieved an overall 12.53 percent growth in followers.

Engagement with the similar pages mirrored engagement with the I Remember page: it peaked on June 20–21, the height of the protests, and remained high.

According to the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED), a nongovernmental organization, some of the same Facebook pages were active prior to the protests,targeting opposition candidatesduring the 2018 Georgian presidential election. In fact, many of these pages had been created in 2018.

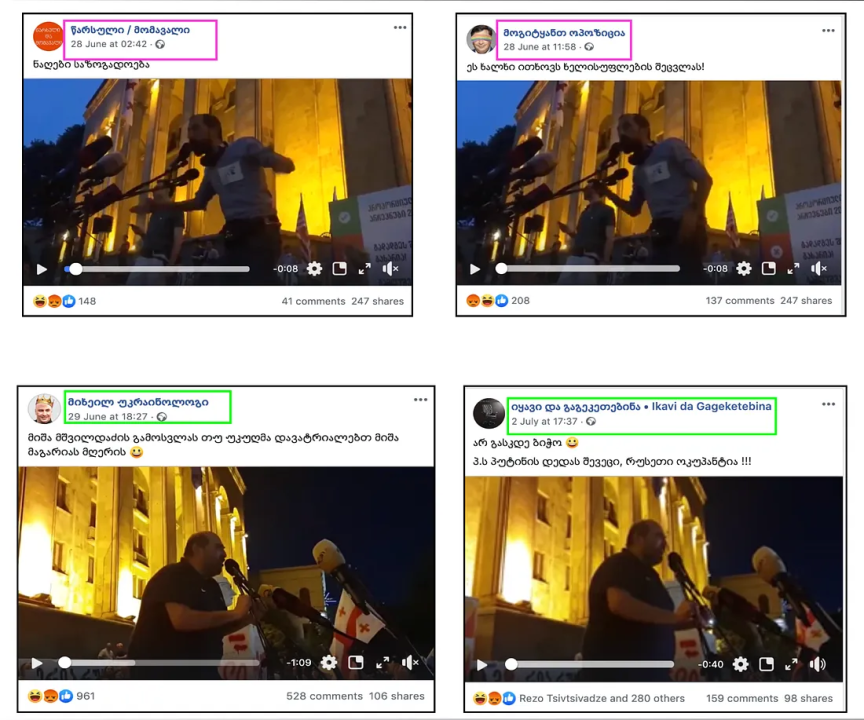

Much of the content posted to these pages consisted of identical photos and videos that were often accompanied by highly similar text targeting the demonstrators.

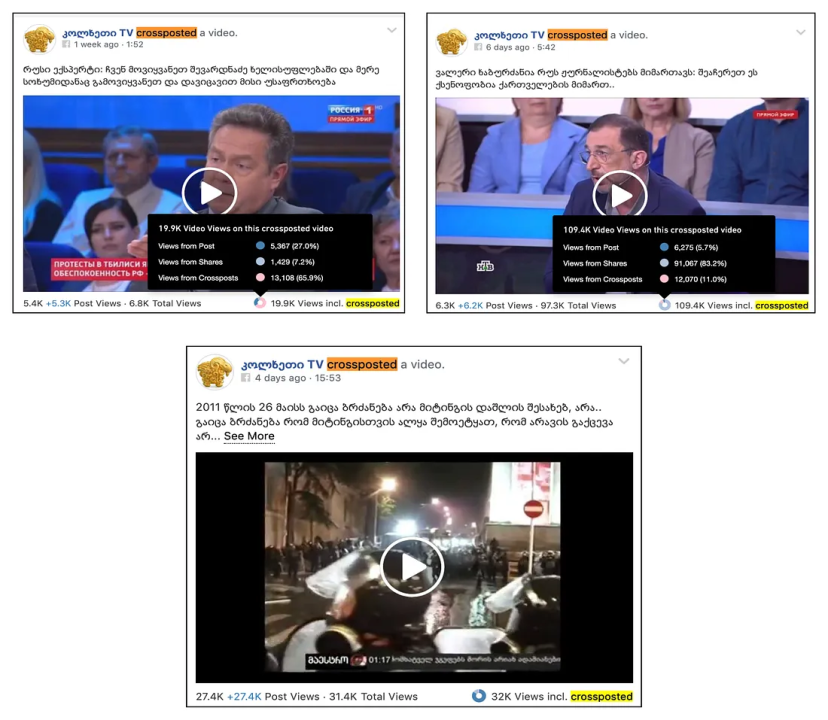

Another sign of possible coordination was crossposting, which involves automatically posting the same video across multiple Facebook pages. The technique offers page administrators several benefits, including granting them permission to post the same video as other pages, reusing videos that have already been posted, providing access to a consolidated view counter that counts video views across all instances of the video, and permitting them to share the video through original posts on their pages rather than sharing from each other’s pages. The page კოლხეთიTV (“Kolkheti TV”), among others in the set, engaged in routine crossposting.

The extent of crossposting and the high degree of content similarity across the pages may indicate a possible coordinated information operation; it does not provide conclusive proof of one, however.

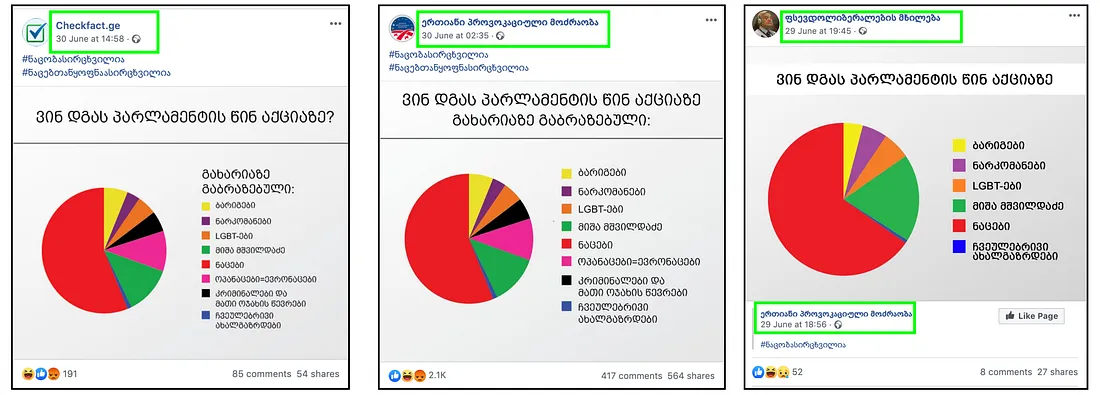

In addition to posting photos and videos, the pages shared pie charts that classified demonstrators as drug dealers, drug addicts, LGBT activists, members of the opposition, or criminals. The biggest slice of the pie — shown in red — suggested that the protests had primarily been attended by members of the opposition. While the pie charts lacked any evidentiary basis, they nonetheless served as an engaging visual.

Thus far, these pages have achieved moderate audience engagement and a steady increase in followers. On both fronts, they show no signs of slowing down. As the protests in Tbilisi will likely continue until the activists secure their chief demand — the resignation of the interior minister — these pages have a significant opportunity to continue to amass and influence Georgian Facebook users.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.