Facebook’s Ukraine Takedown: Personas Pushed Anti-Ukraine Content

DFRLab found “Aleksander Viktorovich” and other personas spreading anti-Ukraine narratives on external websites

Facebook’s Ukraine Takedown: Personas Pushed Anti-Ukraine Content

DFRLab found “Aleksander Viktorovich” and other personas spreading anti-Ukraine narratives on external websites

This article is the second in a series analyzing the set of Facebook pages targeting Ukraine removed in its July 25 takedown. Our previous research on the takedown analyzed five pages amplified divisive content related to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution, and other pro-Kremlin messaging.

After receiving the name of a page from Facebook ahead of a takedown, the DFRLab uncovered a number fictitious or pseudonymous personas — and one apparently real journalist — all connected to anti-Ukraine content on a series of external websites.

As part of a takedown of pages engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior, Facebook removed 83 Facebook accounts, two pages, 29 groups, and five Instagram accounts focused on Ukraine, with particular interest in the Luhansk region of the country. Luhansk, along with the Donetsk region, has been the site of a prolonged conflict between the Ukrainian military and separatist forces backed by Russia since 2014.

In its announcement, Facebook stated:

The people behind this activity used fake accounts to impersonate military members in Ukraine, manage Groups posing as authentic military communities, and also to drive people to off-platform sites. They also operated Groups — some of which shifted focus from one political side to another over time — disseminating content about Ukraine and the Luhansk region.

Facebook shared the name for one of the pages –Александр Викторович (“Aleksander Viktorovich”) — with the DFRLab prior to removing it. In analyzing this page, the DFRLab uncovered five to six external websites and multiple personas that published recycled posts from one another and from other outlets, echoing pro-Kremlin narratives on Ukraine. There was limited to no evidence of direct coordination between the websites or the personas, though the overlap of content between them was extremely high.

Despite these efforts, the Facebook posts accumulated virtually no interactions.

The “Aleksander Viktorovich”/“Max Max” Persona

The Aleksander Viktorovich Facebook page, which had 928 likes and 926 followers, was created on March 9, 2018.

The activity of the page was very low, with only a handful of posts. The only original post by this page was a criticism of the Ukrainian government.

The page promoted two disinformation narratives that have been present in pro-Kremlin disinformation campaigns for a number of years: that Ukraine is a failed state, and that the 2013 Ukrainian revolution was a coup d’état sponsored by the West. Both narratives aim to undermine Ukraine’s image for a domestic as well as international audience. On the domestic side, these narratives present Ukraine as a country incapable of maintaining autonomy, instituting reforms, and making societal progress. On the international side, these narratives present Ukraine as an unreliable partner.

Additionally, an image shared by the Aleksander Viktorovich page created a false equivalency between the Islamic State’s destruction of an ancient monument in the historic city of Palmyra, Syria, and Ukraine tearing down a Soviet-era statue of Hryhoriy Petrovsky in the city of Dnipro. Petrovsky was head of Soviet Ukraine in the 1920 and 30s and one of the masterminds of the mass famine known as the Holodomor, which killed millions of Ukrainians. In 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament approved bills intended to decommunize Ukraine and banned communist symbols in the process, thereby forcing the statue’s removal as a legal requirement.

The image shared on the page received very little engagement, at just two reactions and three comments.

Facebook also removed an individual user account also named “Aleksander Viktorovich.” This user served as the administrator of the page by the same name.

The user account of Aleksander Viktorovich had a handle name of “@MakcMakccs” (or “Max Max”) and primarily spread biased narratives about the war in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. The account published several political cartoons, the first of which showed a caricature of the European Union shaping the brain of a Pinocchio-like figure wearing the colors of the Ukrainian flag, and the second implied that the United States was engaged in rewriting history.

The text accompanying both cartoons promoted several false narratives: that Russia is not involved in the Donbas region and it is Kyiv who is attacking the villages and settlements in the region, bringing ruin and death; that Ukraine is turning to Nazism and Fascism, a frequently used disinformation narrative by the Kremlin; and that the army of the self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic is better trained now than it was in 2014, so it is perfectly prepared to resist Ukraine’s security services.

A Series of External Websites

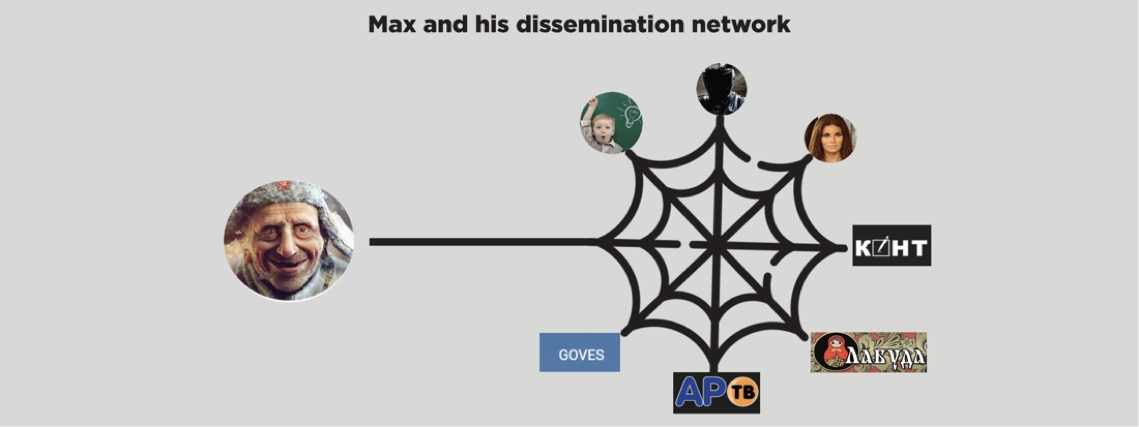

In the course examining the Facebook page and its associated account, the DFRLab identified six websites that featured identical content promoting pro-Kremlin narratives in Ukraine. Five of the websites heavily featured recycled, and possibly plagiarized, content; those websites were goves.net, Newskog (newskog.ru), cont.ws, ARTV (artv-news.ru), and labuda.blog. A sixth website, Rusdozor (rusdozor.ru), may have served as the origin for much of the content, as none of the fictitious or pseudonymous personas uncovered posted to the site.

The “About” section of the Aleksander Victorovich page linked to a website called goves.net. The website identified itself as the “social media of Novorossiya.” This Russian term, which translates to “New Russia” and references eastern Ukraine, is often deployed by Russian officials, including President Vladimir Putin, in an effort to suggest that these territories are not really Ukrainian but firmly within Russia’s historical sphere of influence.

Following the Facebook takedown, goves.net updated its interface. As such, it is important to note that the analysis and screenshots included in this report are based on the site’s old design.

On the website’s old homepage, users could navigate to blogs, news, a user forum, a chat, video content, and online games. The site claimed to have 2,322 users. The DFRLab observed that there were no users online during the course of the workday, however. Furthermore, the counter of visitors revealed that the website was visited 599 times on July 25, 2019, with only 336 of those visitors identified as registered users.

The webpage aggregated news from the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics and provided negative coverage of Ukraine and international affairs more generally. The search bar under the section of Ukraine — news section topic revealed an author nicknamed Макс-Макс (“Max-Max”) — a name similar in spelling to the nickname handle of both the Alexander Viktorovich Facebook page and user account.

The second of the websites, Newskog, describes itself as a media outlet that publishes “trustworthy news.” Despite this, Newskog serves almost exclusively as a self-publishing platform. The website features a simplistic design and focuses mostly on developments in Ukraine, especially those taking place within the last six months. The website is so intently focused on the country that even the “News of Russia” submenu leads to news about Ukraine and primarily recycles anti-Ukraine narratives common to the main pro-Kremlin TV channels.

ARTV, another of the websites to feature the identical content, poses as a media outlet that publishes news. The website also features a blogging section that allows anyone to publish their own content seemingly without ARTV editorial oversight. The most recent post from the ARTV account that posted exclusively news has a date of February 27, 2019. ARTV, like Newskog, focuses mostly on developments in Ukraine, especially those taking place within the last six months.

Like the other sites, the fourth website, cont.ws, also serves as a blogging platform. The homepage features articles on a wide range of topics, from fashion, history, conspiracy theories, critiques of Russia’s adversaries, and general pieces on the blending of democracy with fascism. The Max Max persona actively posted to this website.

Labuda.blog, the fifth website, is a blogging platform on which registered users can share their pieces on one of the 35 different topics ranging from sports and fishing to politics and archeology. The articles that the DFRLab analyzed were published under “Politics” section of the website. Max Max also posted to this platform.

The sixth and final website the DFRLab analyzed was Rusdozor.ru, which publishes on a wide array of topics, including religion, Russia’s role in the world, and Ukraine, often focusing the Donbas region. Rusdozor appeared to be an outlier, however, as it appears to be the source of the content plagiarized across the other websites.

Rusdozor, however, rarely publishes unique content and instead frequently reposts news from Russia 24, a pro-Kremlin TV channel, or from other pro-Kremlin blog platforms. One part of the website focuses on declaring the autonomy and origins of the Ukrainian nation to be incorrect or false, citing pro-Russian historians and experts.

None of the fictitious or pseudonymous personas identified by the DFRLab posted to Rusdozor. That said, pieces written by a journalist from the Luhansk region of Ukraine and posted to Rusdozor were frequently republished under a different name on the other websites detailed above.

The Personas

While Max Max appeared to be the most prolific persona, and the only one obviously connected to the removed Facebook assets, many of “his” written pieces appeared with identical text but under different bylines on the six sites detailed above as well as on social media.

The next name the DFRLab examined appears to be legitimate: “Artem Porvin” seems to be a real journalist from the self-proclaimed Luhansk People’s Republic and features heavily on Rusdozor. Porvin also published original pieces on other Luhansk-focused websites.)

The DFRLab was able to identify most of the other personas because they were reposting verbatim content originally posted by Porvin on Rusdozor. The DFRLab found no other connection between Porvin and the other personas outside of the content that appears to have been plagiarized from his writings.

Similarly, the other personas analyzed by the DFRLab presented similar and related behavior — e.g., reposting the same content to the same series of websites — but there was limited evidence to tie them directly to each other.

The other likely pseudonymous or entirely fictitious personas across the websites included Анна Люберцева” (“Anna Lyubartseva”), “HnumRA,” Владислав Орехов (“Vladislav Orekhov”), Владимир Луганский (Vladimir Luhanskiy), Макс (Max), Никита Мирный (Nikita Mirniy), Степан Иванов (Stepan Ivanov), Базилио (Bazilio), and “Trueman.” The list is not exhaustive, though — there may be other personas replicating the same content.

The personas had many of the common identifiers of false presentation: anonymous or stolen profile photos; profiles on the websites with minimal to no background information; a lack of a broader online fingerprint; and inconsistent use of the personas. Often, an article by Porvin would be copied directly to other websites, each under a different name.

Some of the personas were more prolific than others.

Anna Lyubartseva, for example, was widely active on the same platforms as Max Max. The focus of “her” writing was similarly on negative coverage of Ukrainian army and politics. The various Lyubartseva accounts used non-specific or “borrowed” profile pictures, allowing the operator to remain anonymous. The Lyubartseva persona was active on all of the above platforms as well as on Russian social media platform VKontakte (VK), where “she” used a photo of a young Raquel Welch as “her” profile photo.

Some personas were only active on only one of the websites. “HnumRA,” for example, posted exclusively on Newskog where it was cited as the author of articles that were republished elsewhere under the “Anna Lyubartseva” persona. It is possible that Lyubartseva was also plagiarizing HnumRA’s content.

Similarly, the Vladislav Orekhov persona only posted on Cont.ws. The stories posted by Orekhov were in line subject matter-wise with those published by Lyubartseva and Max Max. One of Orekhov’s pieces appeared to be taken verbatim from a piece on Rusdozor posted under Artem Porvin’s byline.

Personas in Action

The personas often published the same content across the websites but under different bylines. The content included, among other things, pieces plagiarized from Porvin, reposted links, and seemingly original text, sometimes stolen from other outside sources.

The Max Max Facebook page also shared a Twitter account, which has also since been suspended, with the handle @Ded_Maxim_. The Twitter account shared articles from Newskog; the articles featured a byline from a user named “Макс Макс” or “Max Max.” A Google search of text from this article revealed that several other platforms carried the same text. All of these articles were by Max Max. Of all these platforms, only Labuda.blog provided a link to its source: cont.ws.

One of the posts on the Aleksander Viktorovich Facebook page concluded with a copyright sign — implying it to be wholly original content — as well as the name Max Max. The text search of this particular post revealed connections to a goves.net article under the name Max Max. The text itself was a compilation of the first paragraphs of a 2016 post on Agency of Political News platform, a blog focused on Ukrainian identity. The last paragraph appeared to be original and identified the United States as “the mastermind of the Ukrainian coup.”

The profile icon Max Max used on different platforms also matched a previous profile photo from Facebook. While a final profile picture — a detailed cartoon of an old man in a winter hat — was added on March 20, 2019, the original one from the Facebook page featured a boy on a green background, an image that matched the profile photo used by Max Max elsewhere on the external websites.

Some articles credited to Max Max on one website were credited to other personas on other websites. For example, an article published on cont.ws by Max Max also appeared under Lyubartseva’s name on ARTV — Max Max also posted to the latter website.

These accounts may have served as sockpuppets operated by the same person or entity in an effort to amplify anti-Ukraine messaging. A search of the names “Max Max” and “Anna Lyubartseva” led to their social media profiles on Facebook and VK. Neither account published identifying information; instead, they published the same articles, indicating that both used social media primarily as a means of amplifying the same content.

The operator concurrently posted identical text from a Newskog story, written under the “HnumRa” persona, as “Anna Lyubartseva” on three other sites: a VK group with 19,000 followers, ARTV, and cont.ws. The theme of the story resembled that of the kind often spread by Max Max: general critique and discrediting of the Ukrainian army and government.

Groups on VK were a particularly favorite vector for the operation to spread content from cont.ws; VK is one of the most widely used social media platforms in Ukraine, as well as in Russia, making it a particularly effective means of disseminating content.

These posts followed a pattern. They were usually short (three to four paragraphs each), where the first two to three paragraphs are copy-pasted verbatim from blogs, news outlets, or other sources. The conclusion, however, was often unique or copied from other sources. Sometimes, the entire article was a compilation of excerpts from many sources.

In addition, the photographs accompanying the articles were often lifted from other media outlets. In an article by Anna Lyubartseva on Newskog, for example, the operator repurposed an image originally published by the BBC in 2014.

The operator published the post either under the same name or under different names on “news platforms” that included a self-publishing feature. The engagement of the posts was modest; often, it was close to zero.

Porvin remains a bit of an anomaly in how he was connected to the websites or personas, if at all. Most of the plagiarism seemed to have targeted his stories; for example, one article published under Porvin’s name appeared a day later on cont.ws under the name Vladislav Orekhov. Some of the materials attributed to him on Rusdozor, however, were copies of Max Max’s and other users’ posts on the cont.ws platform. For example, Porvin published one of his articles nine days after the Max Max persona published it on Facebook.

Conclusion

The DFRLab uncovered five external websites publishing possibly plagiarized (and definitely replicated) anti-Ukraine content after receiving a single page name ahead of Facebook’s July 25 takedown. The analysis was largely off-Facebook and unrelated to the removed assets.

While many of the websites characterized themselves as news outlets, they primarily functioned as self-publishing platforms. The websites often featured identical content posted by different and distinct personas. There was little evidence to connect the websites too each other, to tie the personas to one another, or of a direct relationship between the websites and the seemingly artificial personas.

It is unknown whether the websites coordinated directly or if the personas were independently posting to them, often recycling text verbatim from one another. Only one of these names uncovered, Artem Porvin, seemed to be a real journalist, and the DFRLab could not tie the other monikers directly to Porvin. The DFRLab also found no evidence to connect Porvin to the disabled Facebook assets.

Overall, these personas employed various blogging platforms, in tandem with social networking sites, largely to promote pro-Kremlin and anti-Ukrainian content. Despite their best efforts, however, they only achieved a modest impact, amassing virtually no engagement on most of its posts.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.