Inauthentic Sputnik-Linked Pages Target the Armenian Diaspora

Pages and groups tied to Sputnik Armenia employees funneled diaspora to the Kremlin outlet’s content

Inauthentic Sputnik-Linked Pages Target the Armenian Diaspora

BANNER: (Source: @ZKharazian/DFRLab via WikiMedia Commons)

Over the past decade, individuals linked to Kremlin outlet Sputnik’s Armenia branch have cultivated an extensive network of Facebook pages and groups targeting the Armenian diaspora, a DFRLab investigation has found.

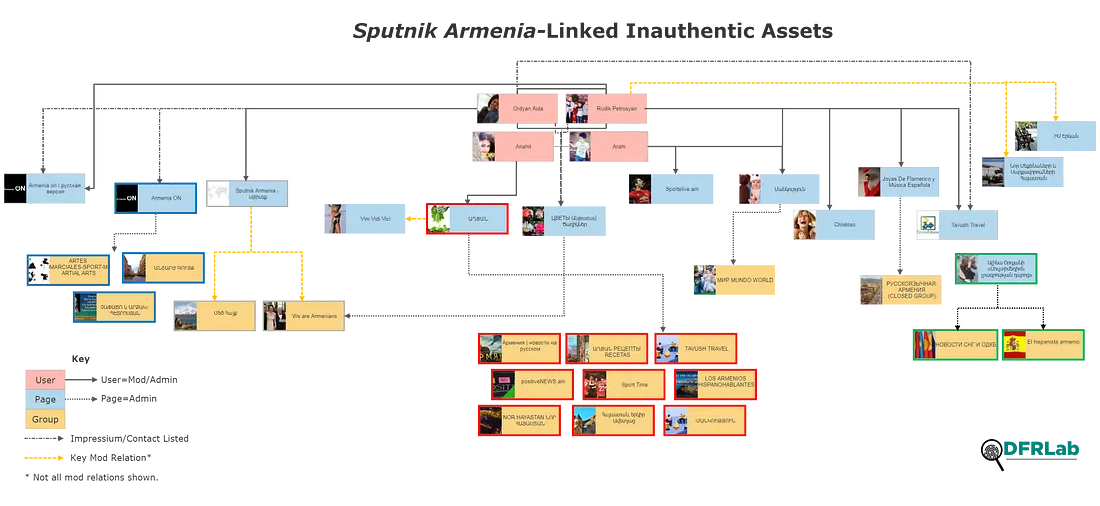

Special interest fan pages devoted to food recipes, sports, and beautiful women, among other topics, administered groups dedicated to Armenian culture, politics, and identity. (On Facebook, both pages and accounts can be administrators of groups.) Almost all of the pages were linked to the profiles of Sputnik Armenia employees and their family members. The groups, meanwhile, served as content amplification platforms for the Sputnik Armenia website, as well as for a second media outlet, ArmeniaON. Prior to publication, the DFRLab shared this story with Facebook, which has since made the independent decision to remove most of the assets in this analysis.

In both strategy and content, this network bore a strong resemblance to another Sputnik operation the DFRLab covered in January 2019. The earlier network, which spanned nearly 300 Facebook pages, also used inauthentic Facebook fan pages devoted to special-interest content to funnel audiences from the Baltics, Central Asia, and the Caucasus to the Sputnik website.

As in the earlier operation, this network’s primary aim was not to promote a cohesive political or ideological agenda. Rather, it seemed focused on building trust and exposure to the Sputnik media brand among an Armenian diaspora audience — albeit doing so via covert means.

Armenia has the largest diaspora community of any post-Soviet state in proportion to its population: an estimated 8–11 million Armenians live outside of the country, in comparison to the roughly 3 million who live within the country. The diaspora is generally politically active with regard to Armenian affairs and plays a critical role in supporting the country’s economic development as well as developing its human capital. For the Kremlin, building a loyal Armenian diaspora audience for a Russian state propaganda outlet establishes a conduit through which it can exercise influence over Armenian society, domestic politics, and foreign affairs.

That much of the network’s content was not political suggested that the operation was in an early audience-building stage. Kremlin disinformation campaigns often start with banal, non-ideological topics to attract a wide audience; at a later stage, they begin to inject that audience’s media diet with Kremlin propaganda. That said, the network also promoted content that inflamed tensions with Armenia’s neighbors, characterized Armenia as a failing state, and positioned Russia as Armenia’s protector.

All in the Family

In all, the DFRLab was able to identify four individual users, 14 pages, and 18 groups as part of this network.

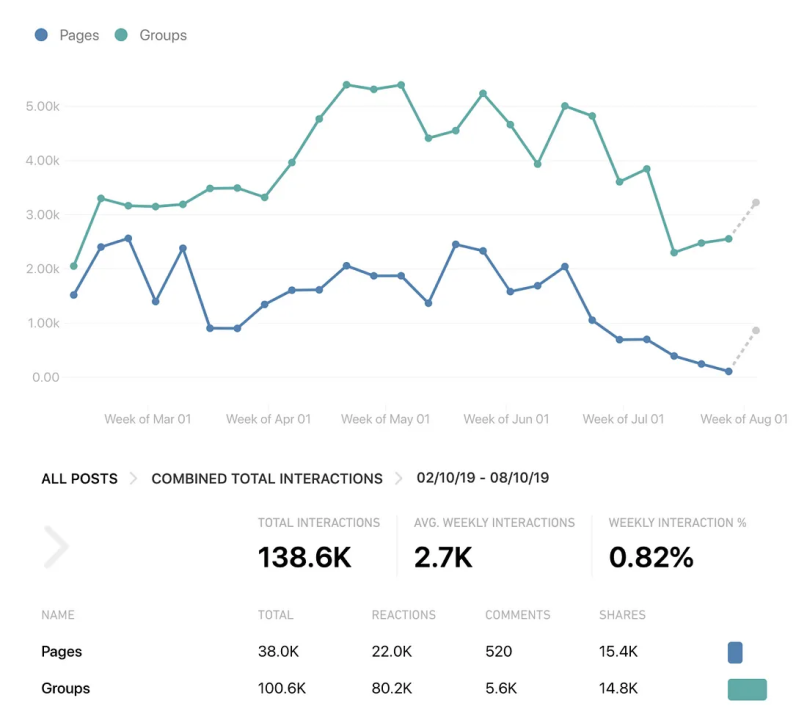

Overall engagement with the network’s assets was moderate, at roughly 138,000 interactions over a six-month period. Notably, the groups, which hosted most of the posts amplifying Sputnik’s content, had significantly more engagement than the pages.

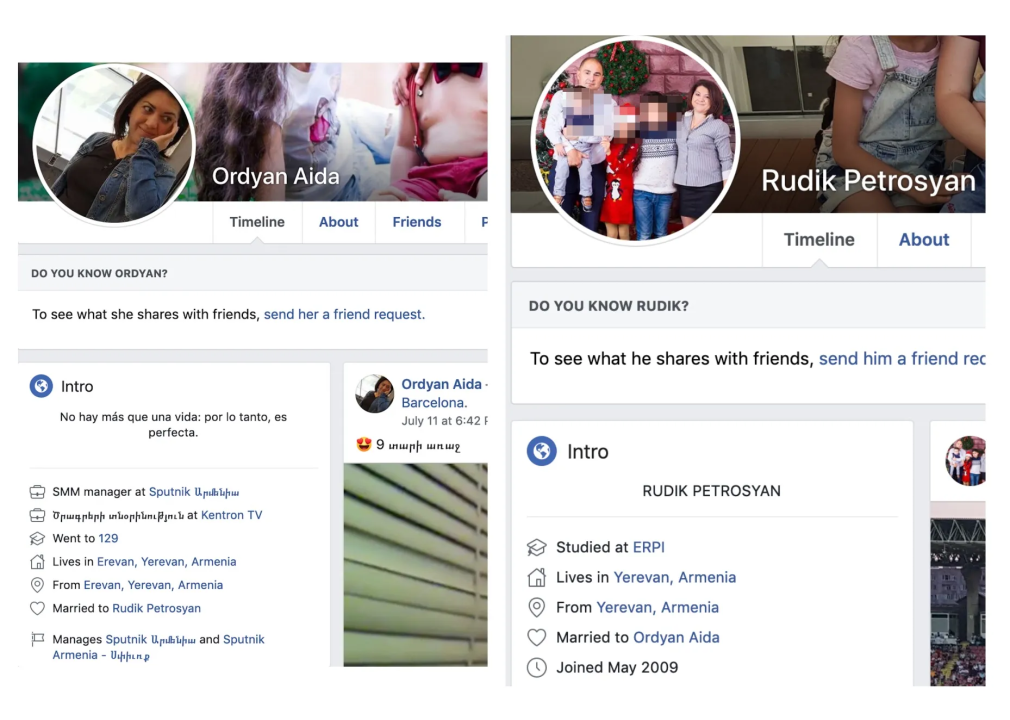

The individual users responsible for running these pages formed an Armenian family. The two adult users, Ordyan Aida (“Aida Ordyan”) and Rudik Petrosyan, indicated that they were married to each other on their Facebook profiles. Aida identified herself as the social media manager of Sputnik Armenia and as the page manager of both the Sputnik Արմենիա (“Armenia”) page and a second page of the same name, but with “Spurk” (“Diaspora”) in the handle.

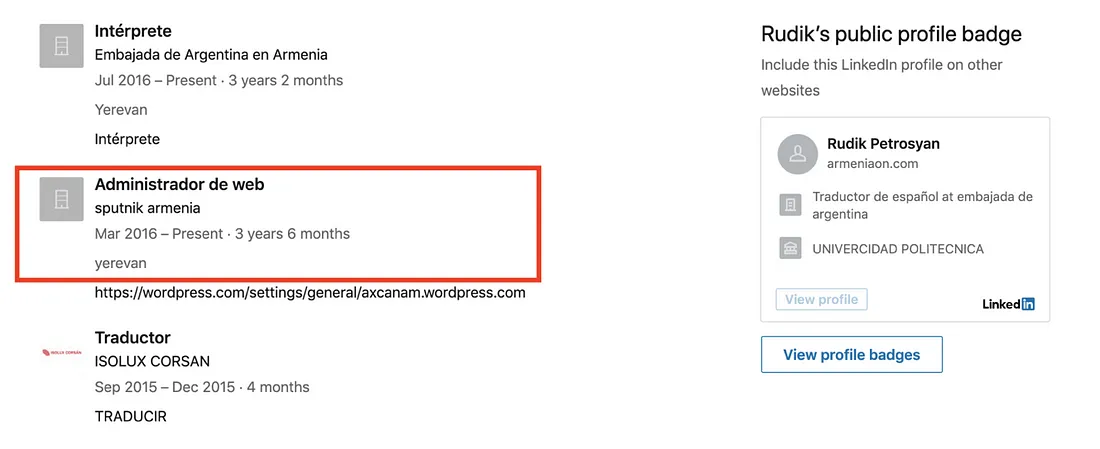

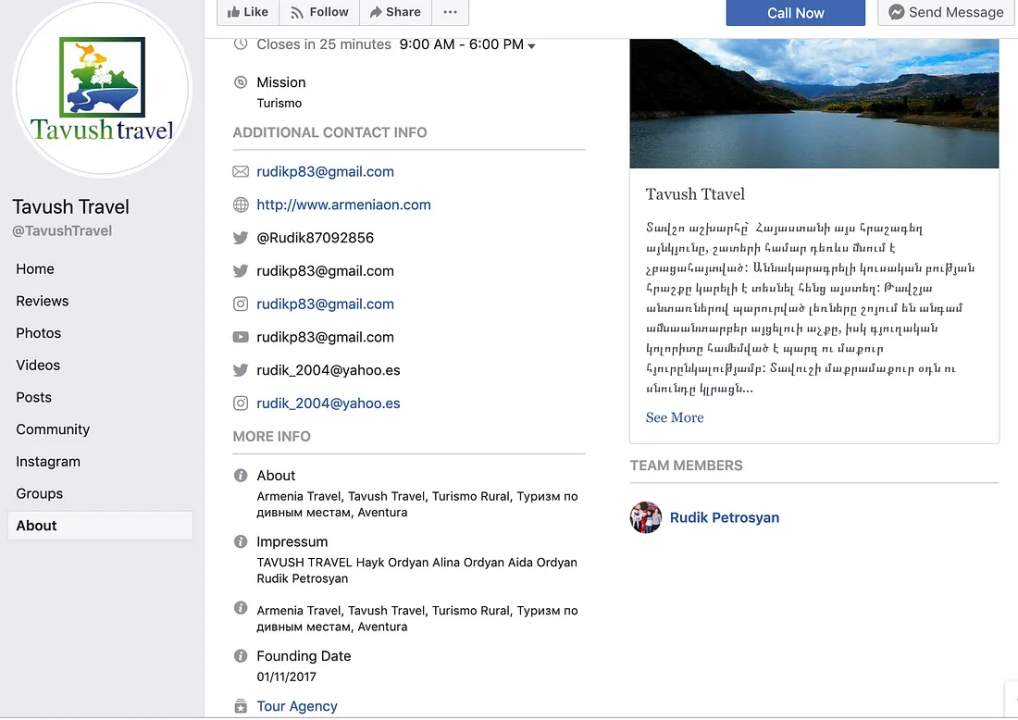

Meanwhile, Petrosyan, on his LinkedIn profile, identified himself as the administrator for Sputnik Armenia’s website.

In addition to Ordyan and Petrosyan, accounts belonging to what appeared to be, according to a family photo posted by one of the accounts, two of the couple’s minor children, a girl and a boy, also played prominent managerial roles in the network. While they may be the couple’s real children, their accounts were likely inauthentic. Their names have been changed and photos blurred to protect their privacy.

Facebook prohibits accounts registered on behalf of children under the age of 13. There were also indications that someone other than the children was likely operating these accounts. The first profile picture on the profile of the young girl, “Anahit,” was what appeared to be a selfie of an adult man — possibly Petrosyan.

Special Interest Fan Pages

The four user accounts belonging to the family members each managed at least one Facebook page, and often multiple ones, devoted primarily to innocuous special interest or lifestyle content such as food, sports, travel, or flowers.

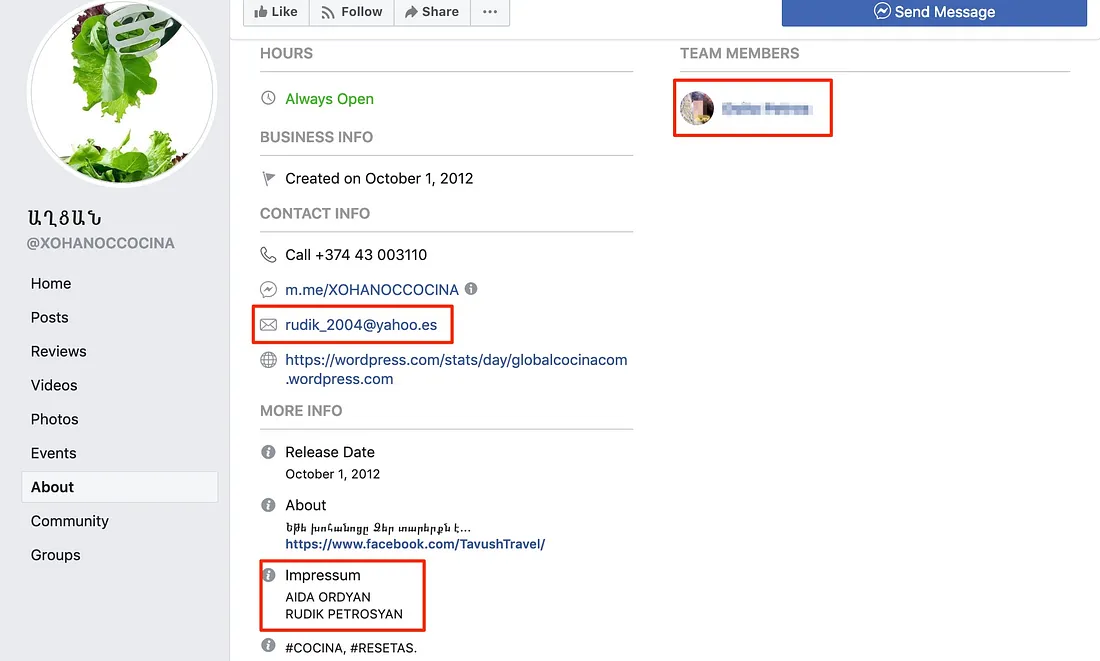

Anahit, for example, managed a page called ԱՂՑԱՆ (“SALAD”). This page primarily posted food recipe videos and lifestyle hacks. Since its creation in October 2012, it had amassed over 20,000 likes, the most of any page in the network.

In 2012, Anahit would probably have been a toddler. The “About” section listed Petrosyan’s email as the contact. The DFRLab reached out to this email address for comment and received no reply.

This page largely stuck to its stated purpose in terms of the content it posted — most of the posts were viral videos of food and lifestyle hacks from other sources.

The account of Anahit’s brother, “Aram,” managed two special interest pages of its own: Մանկություն (“Childhood”) and Sportlive.am. In terms of content, these pages again stuck to their stated purpose: the former posted photos and videos of children, while the latter posted sports content.

News Groups and Amplifying External Websites

While the pages themselves primarily posted innocuous content within their sphere of interest, each page in the network managed and moderated several groups, many of which were devoted to Armenian news, national identity, or the diaspora community. The “SALAD” page, for example, served as an administrator of at least nine Facebook groups, including several groups dedicated to posting news content for an Armenian audience: Армения | новости на русском (“Armenia | news in Russian”), NOR HAYASTAN ՆՈՐ ՀԱՅԱՍՏԱՆ, and positiveNEWS.am.

These groups often doubled as content amplification platforms in which the family accounts posted links to articles on the Sputnik Armenia website and a second outlet, ArmeniaON. The ArmeniaON site hosted different content from Sputnik Armenia but the two outlets may have shared some contributors. In one case, a prior contributor to ArmeniaON, Ruben Shukhyan, also had an author’s page on Sputnik Armenia.

Furthermore, while the ArmeniaON site had no clear ideological bent, it may have had a financial motivation, as it was running three ads on its homepage. One of the ads was for Tavush Travel, a supposed travel agency, which also had a Facebook page called “Tavush Travel” managed by Petrosyan.

Much like the Tavush Travel page, several of the special interest pages in the network directed Facebook users to the armeniaon.com domain.

Targeting the Diaspora

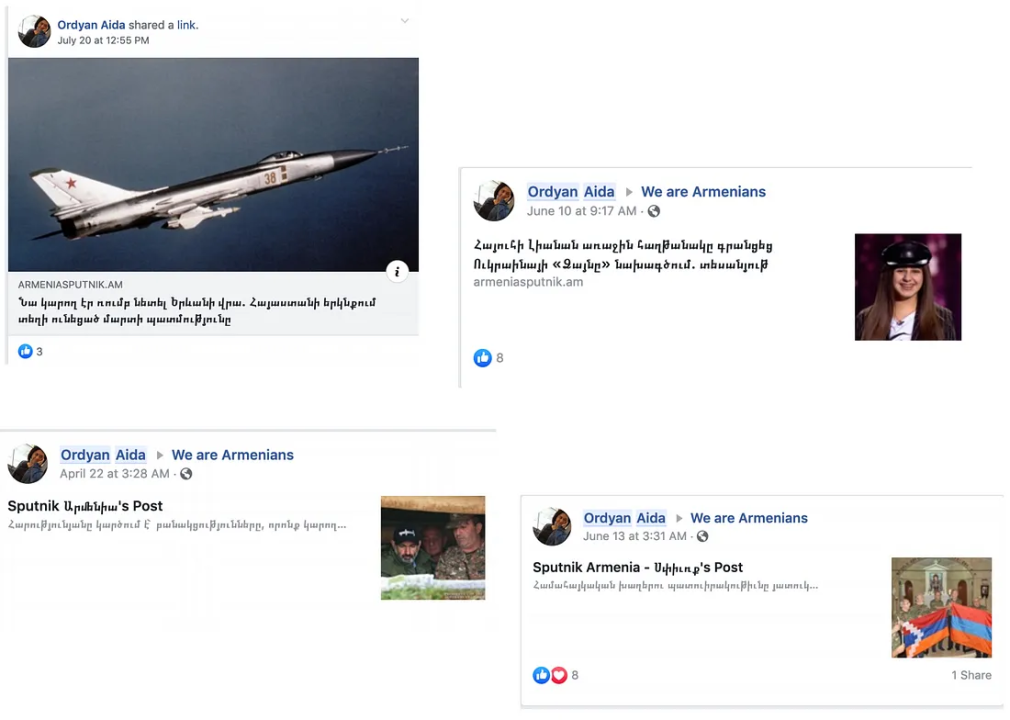

This network specifically sought to attract a diaspora audience. While the main Sputnik Armenia page had roughly 25,000 likes, the follower count of the “Diaspora” page was much smaller, at just about 650 likes. Unlike its main counterpart, however, the “Diaspora” page moderated two groups: We are Armenians and Մեծ Հայք (“Armenia Major”). Using her individual account, Ordyan posted frequently to both groups. Her posts primarily consisted of direct links to articles on the external Sputnik Armenia website.

Ordyan also posted a video from the Sputnik Armenia Play page to the “Armenia Major” group announcing that Sputnik Armenia also published content in Western Armenian — the branch of the Armenian language most commonly spoken by the Armenian diaspora — to make the outlet’s content “accessible to our compatriots living abroad.”

Two of the groups in the network — LOS ARMENIOS HISPANOHABLANTES (“Spanish-Speaking Armenians”) and El hispanita armenio (“The Armenian Hispanic”) were geared toward Armenians in the Spanish-speaking world. Estimates of the size of this community vary, but the largest populations reside in Argentina (an estimated 100,000 Armenians) and Spain (an estimated 40,000.)

These behaviors indicated that this network attempted to first attract a wider Armenian diaspora audience and then introduce that audience to Sputnik’s messaging.

Exploiting Divisive Issues

The times at which Kremlin-related disinformation operations have the highest impact often revolve around the most politically incendiary and emotionally fraught topics. This operation was no different, as it pushed discussion of the Armenian genocide.

To understand fully how Sputnik Armenia and the operators of the network use this issue, it is vital to understand the extent to which painful collective memory of 1915, when the Ottoman Empire systematically exterminated an estimated 1.5 million Armenians, undergirds Armenian diaspora affairs. While acknowledgement of the genocide is widespread among historians, the Turkish government continues to deny it. This denial has continued to provoke intense hostility in Armenia-Turkey relations over the past century, and the genocide is one of the key issues underpinning the advocacy efforts of the Armenian diaspora, many of whose members descend from survivors.

It is the reluctance with which other outlets approach the issue of the Armenian genocide that Sputnik sought to exploit. In invoking and acknowledging the trauma of the genocide, which some mainstream non-Armenian outlets still avoid doing, Sputnik may have attempted to endear itself to an Armenian audience. But in framing the issue so as to draw parallels to Armenian-Turkish relations today, it pursued a particular aggressive tactic: one that inflamed readers’ emotions by prolonging and sharpening the sense of trauma many Armenians associate with 1915, rather than alleviating it.

Several of Sputnik Armenia’s articles drew implicit parallels between the Turkish government’s treatment of Armenians today with the Ottoman Empire’s leading up to the 1915 genocide. One article, for example, asserted that an Armenian boy was forcibly converted to Islam during a live broadcast of a religious program by Turkish theologian Nihat Hatipoglu. For many descendants of survivors, this narrative would invoke the Ottoman Empire’s forced conversion of Armenian Christians living in Turkey to Islam prior to and during 1915.

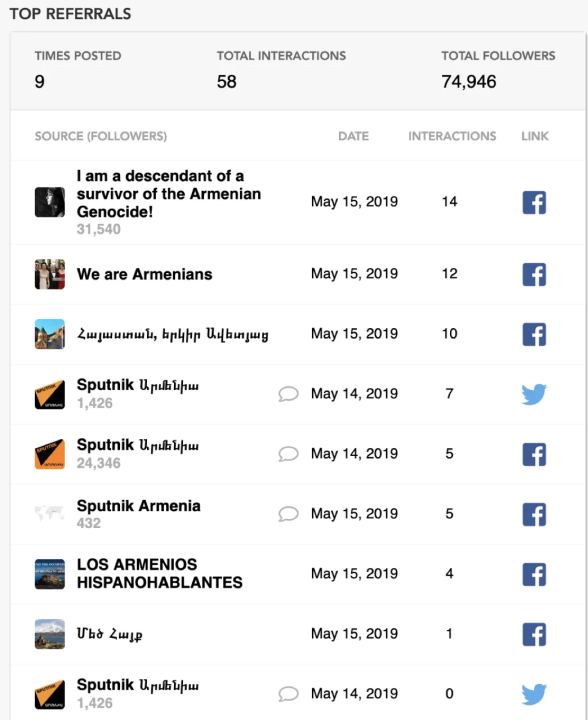

According to CrowdTangle, Facebook’s proprietary analytical tool for its own network, the article about the forced conversion was crossposted to numerous pages within the network.

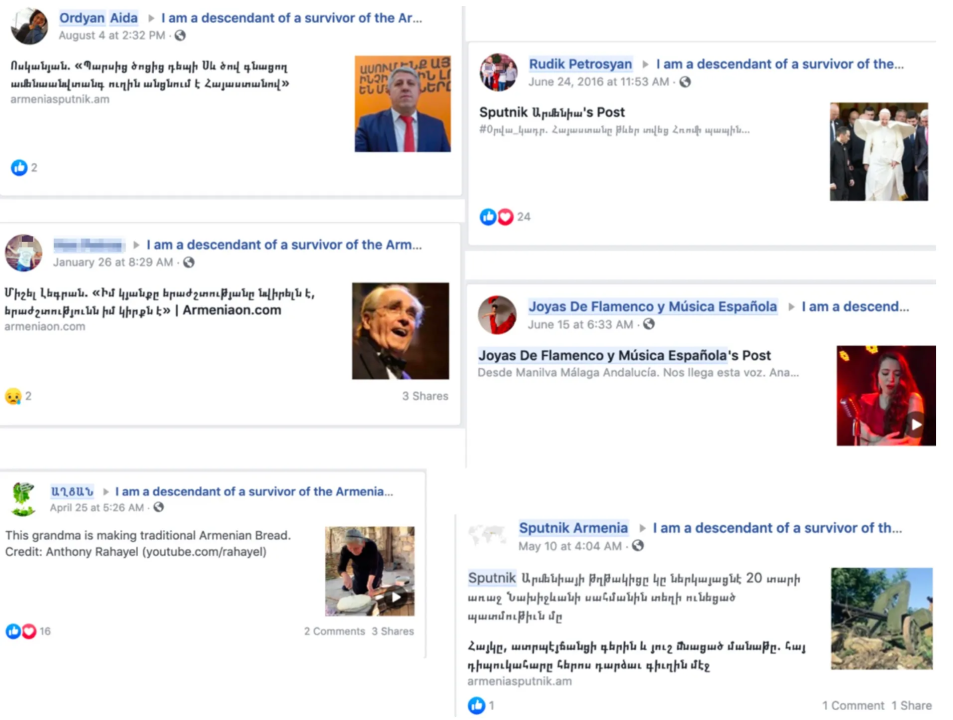

The CrowdTangle analysis also revealed that an account posted the link to the article in a large Armenian diaspora group on Facebook, “I am a descendant of a survivor of the Armenian Genocide!”

The account that posted the link was the Sputnik Armenia diaspora page, which, as noted earlier, Ordyan managed.

In fact, many of the assets identified as part of this network regularly posted to this group.

That the operators of this network regularly posted their content, some of it linking directly to Sputnik Armenia, to an Armenian diaspora group with over 30,000 members indicated that this network likely had far wider reach than its total follower count suggested.

In addition to inflaming tensions regarding the Armenian genocide, the network also promoted content characterizing Russia as Armenia’s protector, as well as content characterizing Armenia as a failing state. In an example of the former, Ordyan shared a story to one of the groups noting that Russian guards had helped prevent narcotics from entering the country. In an example of the latter, she shared a story describing the capital of Yerevan as filled with garbage and crawling with vermin, suggesting that the government cannot provide its own residents with basic municipal services. While local officials in Yerevan have come under criticism for their handling of a waste management crisis, Sputnik has framed the issue in hyperbolic terms, referring to “hordes” of pests descending on the city and calling it a “garbage apocalypse.”

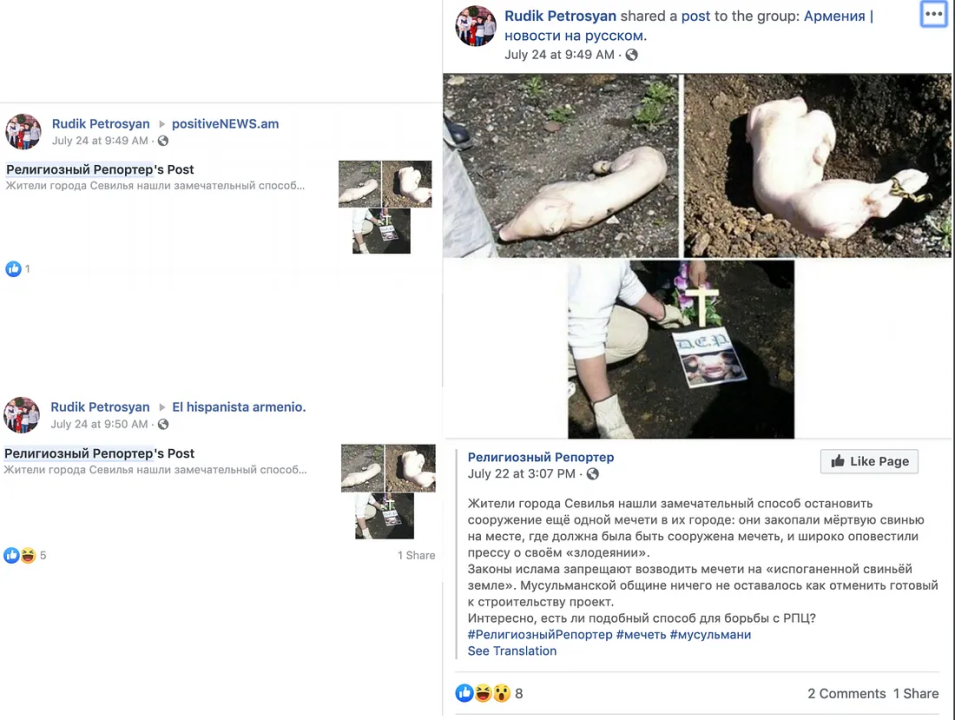

The “Plant-A-Pig” Movement: From the Russian Blogosphere to Beyond

The network also delivered distorted narratives from sources other than Sputnik to its audience. In one case, the DFRLab traced an anti-Islam narrative, pushed by Petrosyan, to a Russian anti-Islam forum. The post, which originated on a different page titled, Религиозный Репортер (“Religious Reporter”), claimed that residents in Seville, Spain, “found a wonderful way to stop the construction of a mosque in their city”: burying a dead pig at the construction site. The last sentence of the post read, “I wonder if there is a similar way to fight the ROC” — a possible reference to the Russian Orthodox Church.

This narrative was likely based on a real incident but ultimately distorted: Sources in Spanish media reported at the time that it was not “the pig-soiled ground” under Islamic law that doomed the construction, but protests on the part of neighbors and lack of funding. The anti-Russian Orthodox Church aside seemed to have been tacked on to the narrative later — its inclusion may have served as an attempt to distract from the core Islamophobic narrative of the post or to appeal more directly to an Armenian Christian, as opposed to Russian Orthodox, audience.

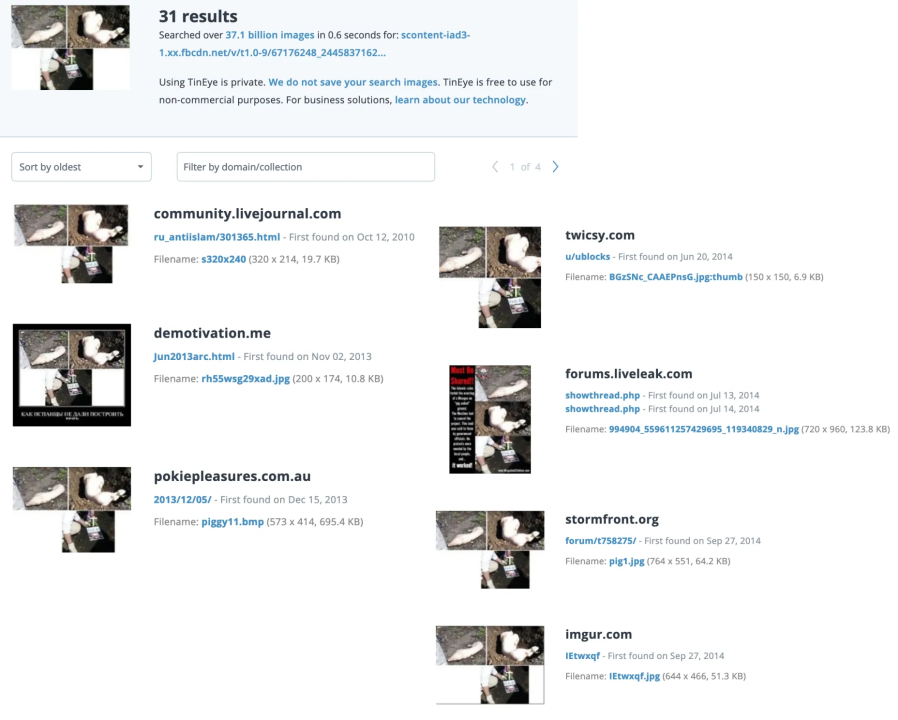

After conducting a reverse image search of the photos included in Petrosyan’s post, the DFRLab found that they have been circulating online for nearly 10 years, but there was no indication in mainstream media sources that they were of the incident in Seville.

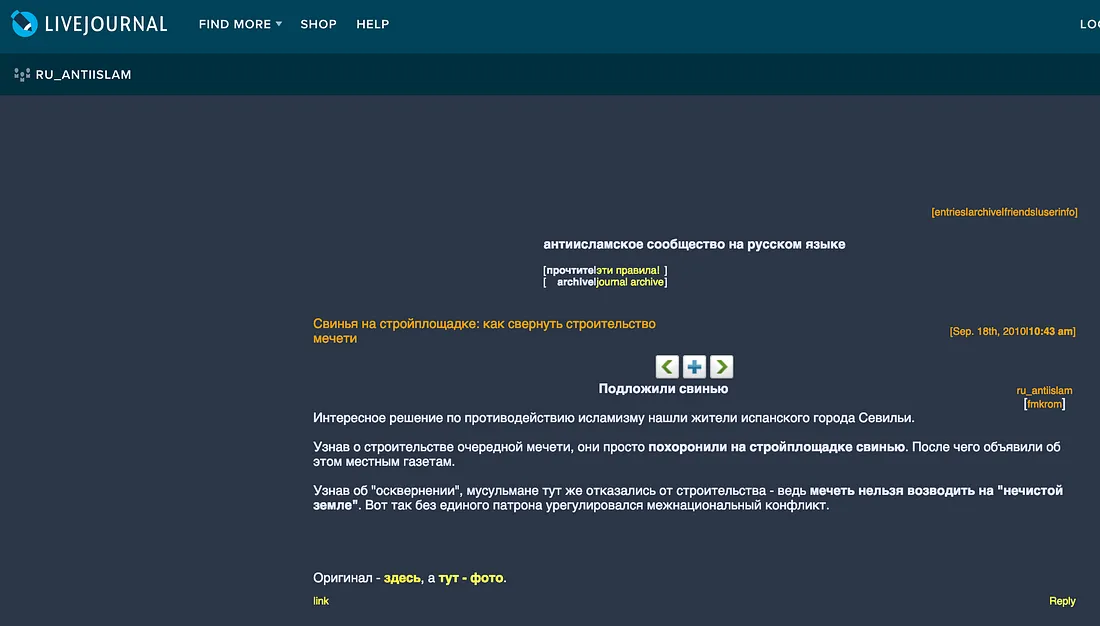

The photos first appeared on a Russian blogging forum –a LiveJournal community called “ru-antislam,” on September 18, 2010.

The TinEye search indicated that, from the Russian blogosphere, the photos migrated to far-right forums elsewhere in the world, including the United States, where it appeared on the white nationalist website Stormfront and the firearms forum GlockTalk.

Conclusion

The DFRLab found distinct resemblances between this network and an earlier Sputnik operation targeting Central Asia, the Baltics, and the Caucasus, which Facebook took down in January 2019 for engaging in “coordinated inauthentic behavior.”

First, both operations involved a significant audience-building component: the use of fan pages devoted to varied, non-political interests to tap into a wider, more generalist audience than Sputnik usually would attract on its brand alone. Second, both obscured the connection between their online assets and the Kremlin news outlet by assigning apolitical fan pages to manage Facebook groups amplifying Sputnik content. The addition of inauthentic children’s accounts managing pages, however, is a strategy the DFRLab had not encountered before.

Even though amplifying the Kremlin’s core political messaging was not the primary aim of this operation, the content promotion model it adopted nonetheless poses a significant risk to digital resilience. In a more politically sensitive context, such as election season, Sputnik could mobilize its ideological propaganda and have a ready-made, brand loyal audience to target that spans the Armenian diaspora.

Future research should examine how widespread these tactics are across Sputnik’s regional bureaus.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.