How a false story about a Cuban COVID-19 vaccine spread in Latin America

Interferon, falsely touted as a coronavirus

How a false story about a Cuban COVID-19 vaccine spread in Latin America

Interferon, falsely touted as a coronavirus vaccine, goes viral across region before jumping to South Africa

This article is part one in a two-part series on how the claim that Cuba had developed a vaccine for COVID-19 spread around the world. Part two will focus on the misleading claim’s impact in South Africa.

In the beginning of February, Cuba announced via official channels that a Cuban-manufactured drug was being used to treat COVID-19 cases in China. Soon after, a Brazilian politician and a Mexican regional newspaper picked up the story. Both, perhaps inadvertently, made a small but significant change to the story: in the new version, the story claimed that Cuba had developed a vaccine for the novel coronavirus.

Since then, the claim that Cuba had developed a vaccine for COVID-19 has reverberated on Twitter in different Latin American countries, until it reached Brazilian hyper-partisan media and left-wing influencers on March 12. On that day, “Cuban vaccine” reached the trending topics in the country. The story spread further to other continents, with a mayor from a South African town promising the population he would buy the Cuban vaccine for his people.

The case illustrates how partisanship can play a role in the spread of false stories. One school of thought for why people believe in false information claims that people tend to more readily accept information that confirms one’s existing beliefs. In this case, strong existing convictions may have primed leftists to believe that Cuba, a communist country, had developed a cure for the novel coronavirus before capitalist countries had.

Interferon and Cuba’s healthcare system

Interferon Alfa-2B is among the dozens of drugs that China used to treat COVID-19 in the country, according to Cuba. In the past, the anti-viral was effective in the treatment of other conditions, such as hepatitis and leukemia. Medical research has yet to prove, however, if it is at all effective in treating infections caused by the novel coronavirus. Interferon Alfa-2B is produced by the Cuban-Chinese joint venture ChangHeber.

Despite not originating in Cuba, interferon-related drugs are a flagship product of the country’s developed biotech industry. Cubans learned to produce interferon, including Alfa-2B, after a group of Cuban health professionals spent time in Finland working with a doctor that had isolated it in the 1970s. The drug was first developed and used on the island against a deadly dengue fever epidemic in 1981. After that, the Cuban biotech industry continued to develop, despite the U.S. embargo, and is now regarded by the regime as a crown jewel for the country’s international prestige.

The Cuban healthcare industry is also used as a source of revenue for the country, as well as a soft-power tool. Doctors are currently Cuba’s largest export, bringing some $11 billion to the country per year — outperforming sugar, tobacco, and tourism in revenue. Cuban physicians have worked in Brazil and Venezuela, and helped with efforts to fight Ebola in West Africa in 2014 before joining the fight against SARS-COV-2 in Italy. The perception of Cuba as a bastion for social welfare, however, is a misguided one, as it obscures the country’s poor human rights record.

First mentions

On February 6, Water Sorrentino, vice president of Brazil’s Communist Party, tweeted a link to an article published by Sputnik Mundo, the Spanish version of the Kremlin outlet, about Cuban interferon. Sorrentino wrongly claimed that interferon was a vaccine rather than a drug. Despite being followed by politicians and journalists, this tweet did not get traction and was only retweeted twice.

More impactful was a similar incorrect claim made by a Mexican news outlet. On February 7, 2020, Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel tweeted an article published in the state newspaper Granma about how Cuban interferon was being used to treat COVID-19 in China. The post was retweeted some 5,200 times and liked 6,900 times.

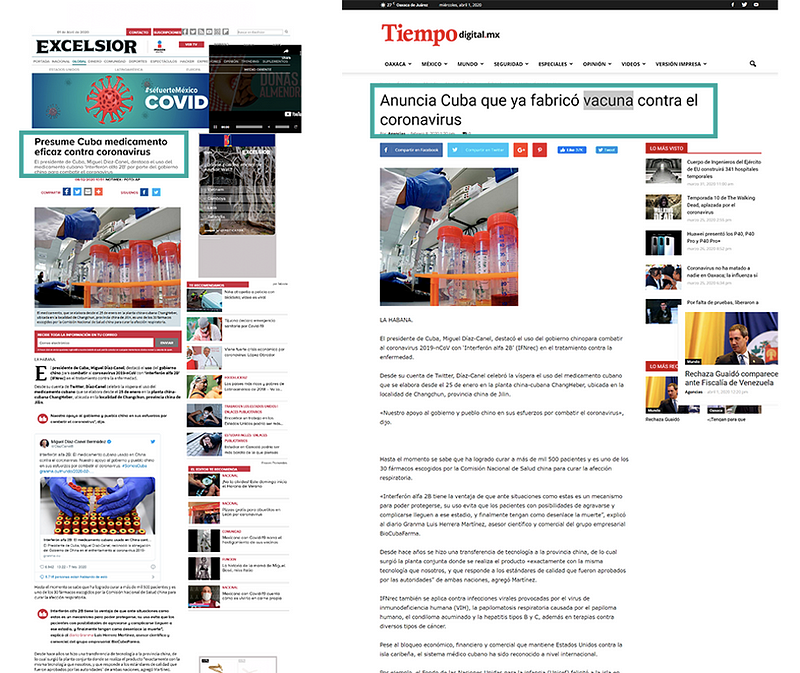

The next day, the Mexican outlet Excelsior accurately reported on Cuba’s claims about interferon, and how the drug was being used in China. The article, however, was republished on the same day by the regional Mexican website El Tiempo Digital. Despite reproducing the body of the article exactly how it was published, El Tiempo made a fundamental change to the headline, which claimed that interferon was a vaccine, rather than a drug.

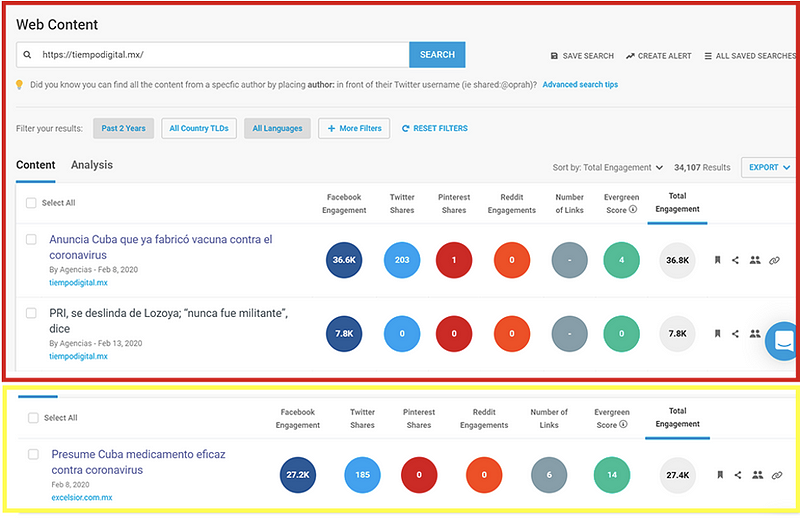

The article with the wrong headline was the most engaged-with article published by El Tiempo Digital in the past two years. It received some 36,800 social media engagements, including likes, shares, and retweets. This is a significant level of engagement for this website; the second most-engaged with article published by El Tiempo Digital garnered 7,800 engagements.

The misleading article also garnered more engagement on social media than the original article posted by Excelsior, which received 24,700 engagements. El Tiempo’s misleading article overperformed Excelsior’s accurate one, despite the fact that Excelsior has 2.2 million Facebook followers, compared to El Tiempo 11,459 followers.

The early life of the “Cuban vaccine” story already bore traces of ideological spin. The article was shared to pages and groups aligned with left-wing movements, such as “Latin American Revolutionary Movement” and “Open Veins,” in reference to Eduardo Galeano’s book about how the subcontinent was exploited by Europeans.

After that, the story kept resurfacing online, primarily being picked up by left-wing accounts. In Chile, accounts tweeted that while Cuba had already developed an “experimental” vaccine, Chile was charging citizens for COVID-19 tests. The complaint about healthcare in the country is a grievance aligned with left-wing movements. Meanwhile, in the beginning of March, Uruguayan accounts on Twitter complained that the new president of the country, the center-right Luis Alberto Lacalle Pou, did not invite Cuban leaders to his inauguration, even though Cuba was the only country to have a “vaccine” against the novel coronavirus.

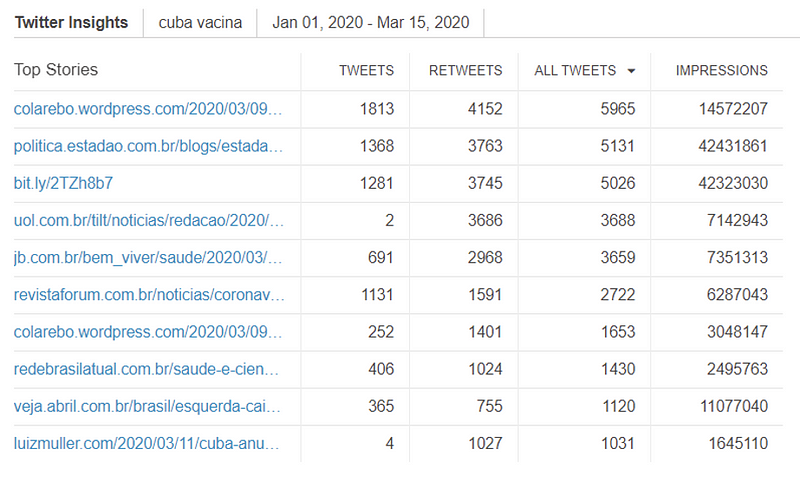

The story gained new momentum on March 9, when El Tiempo’s article was republished by a blog called Colarebo, which stands for “Latin American revolutionary Bolivarian community” in Spanish. The “Bolivarian” in the name might be an indication that this blog is Venezuelan, as “Bolivarianism” is a mix of Pan-American and socialist ideology that is particularly prominent with chavistas in the country. The blog post ended up being the most shared URL in tweets mentioning the Cuban vaccine. The website has a strong anti-American bias, and links to state-run channels from Venezuela and Russia, such as Telesur and RT.

Colarebo’s article peaked on Twitter on March 11. It was mostly tweeted by Venezuelan accounts, which is not unusual, as most of Colarebo’s coverage concerns Venezuela. Venezuela and Cuba are close allies, and Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro has spoken about using Cuban interferon to treat COVID-19 in the country. He did not claim interferon was a vaccine, but rather a drug.

The Brazilian case

A few days after the Colarebo article was published, the topic reached Brazil, the most populated country in the region. This might have been a coincidence, as neither the Mexican outlet nor the Venezuelan ones were mentioned as sources in Brazil.

Still, the story about the Cuban vaccine was published by hyper-partisan websites in the country on March 12, as well as left-wing politicians with national reach. Just as it happened in other Latin American countries, only the headline of the articles mentioned a vaccine; the text mentioned the drug interferon.

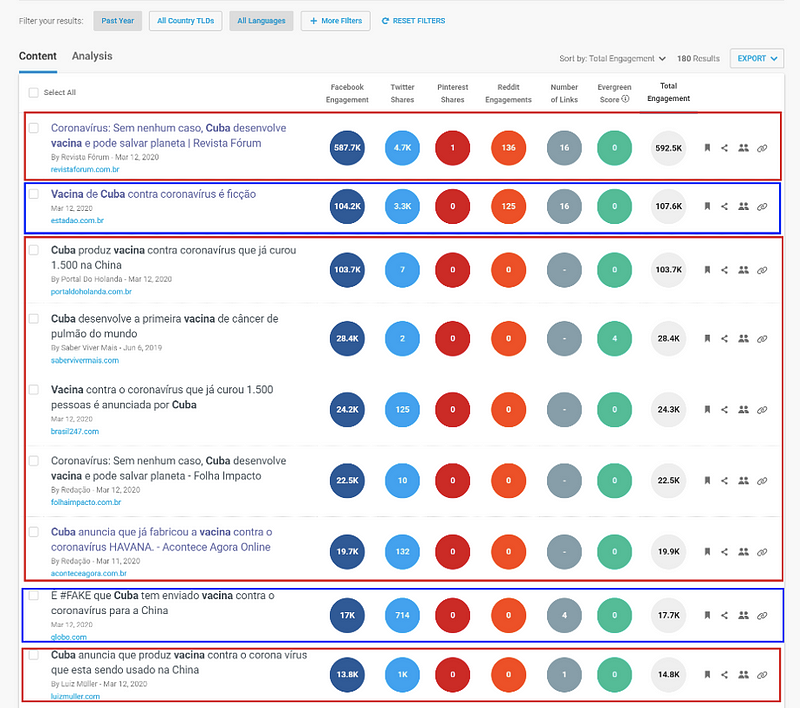

A search made with BuzzSumo showed that seven articles that published the false claim online received some 770,000 engagements on social media. Only one article, published by Revista Forum, received 592,000 interactions. The second most engaged with article about the topic was a debunking article published by the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo. Some 107,600 people interacted with this article. Yet, this is almost one-sixth the number of engagements than the inaccurate article received.

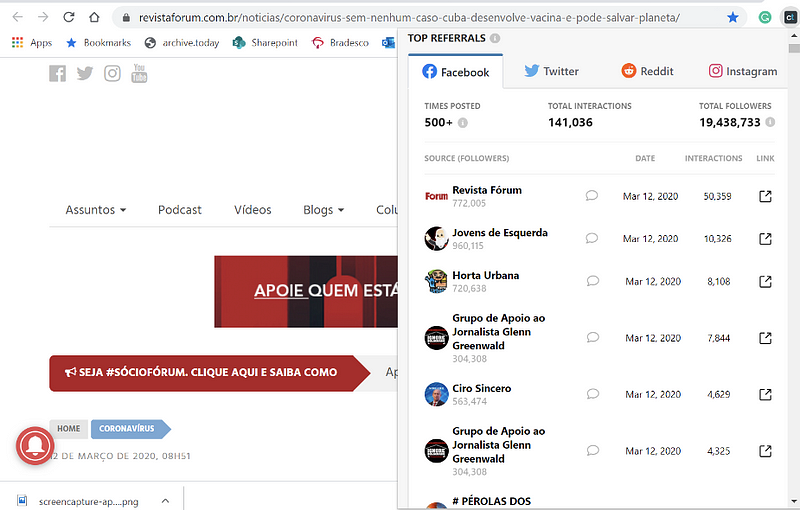

Polarization was visible not only in the publications that shared the false news, but also in the audience that engaged with it. Among the Facebook groups and pages to which the Revista Forum story was shared were a group called “Left-wing youths,” a page supporting the journalist Glenn Greenwald, and one page about the former left-wing presidential candidate Ciro Gomes.

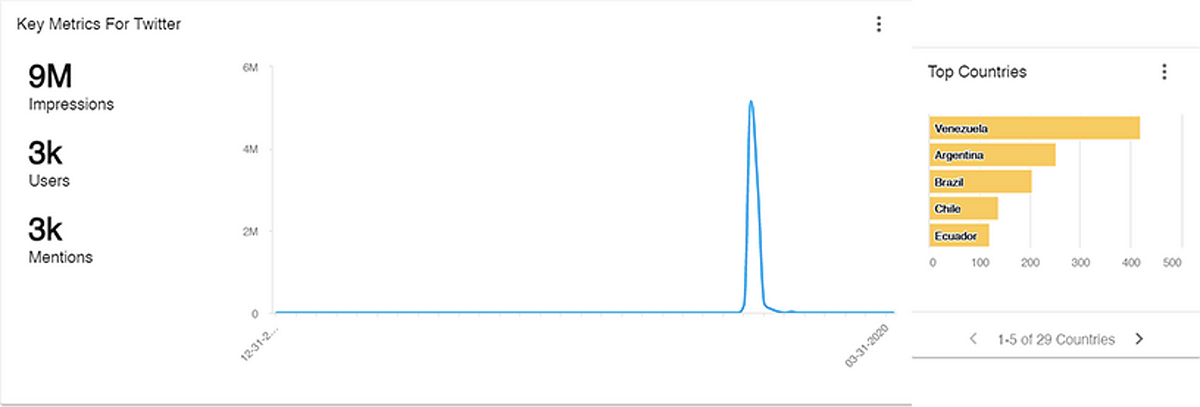

On March 12, the expression “Cuban vaccine,” as well as #Cuba, “And Cuba,” and “vaccine,” trended on Brazilian Twitter, according to Trendinalia. They received at least 50,000 mentions in the country between March 11 and 15, according to a search made with the social analysis tool Meltwater Explore.

Although it is clear that Cuba bragged about interferon as a soft-power tool, there is no open-source evidence to suggest that the country tried to mislead the public into believing that interferon was a vaccine. Most likely, as this article has shown, journalistic errors turned an accurate story into a misleading one, which gained traction online due to ideological polarization.

This case study serves as an example of how partisan beliefs can impact the spread of false stories online. It is likely that leftists believed and shared the story because it confirmed their beliefs about healthcare in Cuba. If this is the case, it suggests that the path to fight problematic information online might lie in trying to reduce polarization, rather than simply correcting inaccurate information published online.

In part two of this series, the DFRLab will analyze how the story about the Cuban vaccine unfolded in South Africa.

Luiza Bandeira is a Research Associate, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.