In Belarus, wave of grassroots activism knocked by unsupported claims of foreign interference

Domestic disapproval of Lukashenko’s 26-year-rule bubbles

In Belarus, wave of grassroots activism knocked by unsupported claims of foreign interference

Domestic disapproval of Lukashenko’s 26-year-rule bubbles over, so he points fingers at Russia and Poland

Despite Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko’s claims to the contrary, there is no evidence that Russia, or any other foreign entity, has spurred the recent outgrowth of Belarusian online activism and demonstrations now flourishing amid increasing dissatisfaction with government officials. As the Belarusian presidential election approaches in August 2020, several initiatives have sprung up critical of the president and his administration, drawing attention to economic stagnation and the repression of political freedoms in the country. Alongside a wave of protests, these include several hashtag campaigns, such as #немойпрезидент (“Not My President”) and #HelpBelarus.

Lukashenko has insinuated that the wave of discontent sweeping Belarus is not the result of authentic grassroots activism, but rather evidence that foreign entities, particularly Russia and Poland, are meddling in the Belarusian presidential election. Russia has certainly exerted political pressure on Belarus to encourage further economic integration with Russia, which Belarus maintains would endanger its sovereignty and Lukashenko’s already shaky grip on power. There is no evidence, however, that the outpouring of civic activism currently underway in Belarus is driven by anyone other than authentic Belarusian activists.

The president has capitalized on anti-Russian sentiment in an effort to consolidate and maintain his power amid mounting disapproval of his rule and a formidable domestic opposition. Lukashenko has been in power for 26 years, having won every presidential election since Belarus secured independence in 1991. Although he is likely to secure another victory in the upcoming elections, this time he faces at least one viable opponent: Viktor Babariko, former chairman of the Russian bank Belgazprombank. Babariko is a member of the country’s political and economic elite, and is not considered to be a “puppet candidate” controlled by a foreign state.

Lukashenko has suggested that Babariko is financing his campaign with money obtained via “financial scams.” On June 18, 2020, Belarus authorities blocked Babariko’s electoral funds and arrested him and his son. He remains in the race with another grassroots candidate, Svetlana Tsikhanovskaya, the wife of Sergei Tsikhanovsky, a popular opposition blogger in Belarus who was arrested for organizing protest rallies in the country.

These barriers to free and fair elections are among a long list of grievances for which Belarusians took to the streets. On May 25, 2020, hundreds of Belarusians in Minsk protested against Lukashenko’s repeated failure to enact social distancing measures and a public health response to COVID-19. The DFRLab has previously covered how Belarusian citizens took matters into their own hands by instituting a voluntary, grassroots-led “People’s Quarantine.”

Lukashenko has suggested that he is willing to resort to physical force to stay in power. On June 23, he called on the military to suppress civil unrest and “protect sovereignty” from “hybrid threats.” The use of Russian meddling in the protests is most likely a convenient way to justify political and civil oppression.

“Not my president”

After the detention of Babariko and his son, social media accounts primarily from Belarus’ digital creative sector started posting content addressed to Lukashenko personally. “I cannot call myself a person who is interested in politics,” wrote a user named Yekaterina, who identified herself as an animal rights activist. “When I look at you, I do not feel anger or disgust, I feel shame.” Another Facebook user named Dima Kurash, who identified as a stand-up comedian, wrote: “Aleksandr Grigorevich, you are #notmypresident. [..] Monopoly of power — no, I do not judge you, but if we lived just fine, and fine — it is not even living good.”

The DFRLab identified at least 29 posts containing the hashtag #немойпрезидент (“Not My President”) on Facebook and that addressed Lukashenko personally. Similar posts appeared on Instagram as well.

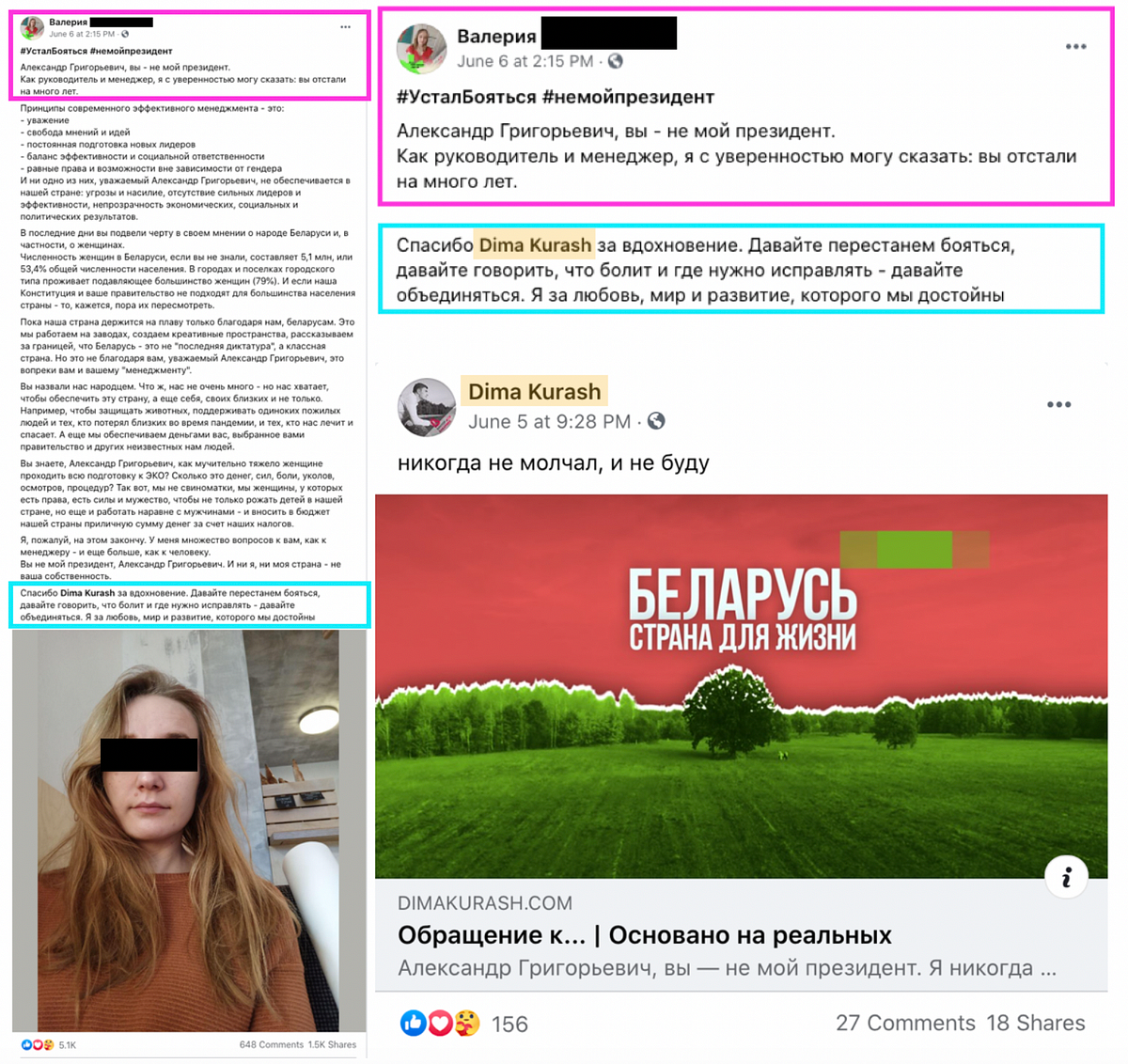

Though Babariko was arrested on June 18, the first post in this style appeared on June 6. Valeria, who identified herself as head of digital at the JCS Digital Agency wrote: “Aleksandr Grigorevich [Lukashenko], you are not my president. As a manager, I can say: you have lagged behind the times for many years.” At the end of her post, Valeria thanked and tagged Facebook Dima Kurash, who inspired her to write a post with the “not my president” hashtag.

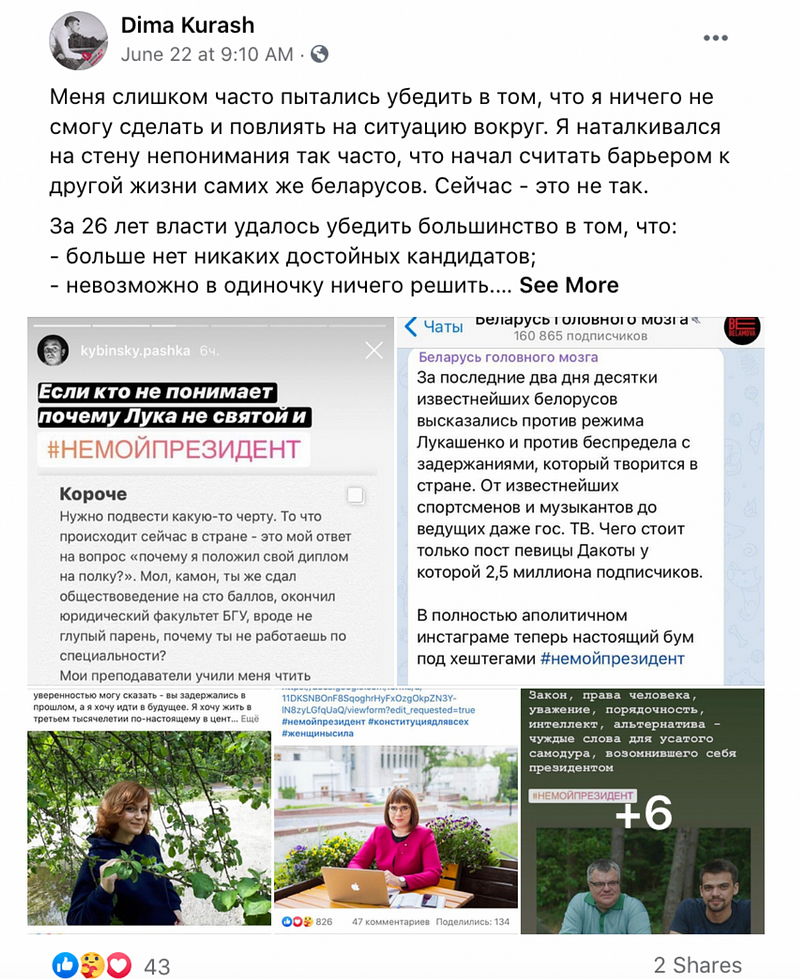

On June 5, the Dima Kurash account posted a link to a blog post that started with the words, “Aleksandr Grigorevich, you are not my president.” Later, Kurash posted a compilation of similar posts on Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram, writing that he had managed to inspire people to speak up against the current regime.

There are several indicators, or rather lack of indicators, that suggest that accounts that engaged in the #NotMyPresident digital flashmob are authentic.

First, their identities can be confirmed via other open source mentions. For instance, Yekaterina, mentioned on her Facebook profile that she is from the city of Gomel and cares about animal rights. Her name appears in a Belarusian media publication about a dog saved in Gomel. Yekaterina is also listed as a volunteer from the Gomel animal rights NGO named Dobrota. Yekaterina has liked the page of the NGO on Facebook too.

Second, they use the same identity consistently on various platforms. Dima Kurash, for example, mentioned that he works at Stand-up Comedy Hall, which is described as “the first stand-up club in Belarus.” His Facebook profile links to his YouTube channel and features footage of him performing stand-up comedy.

Help Belarus (#helpBelarus)

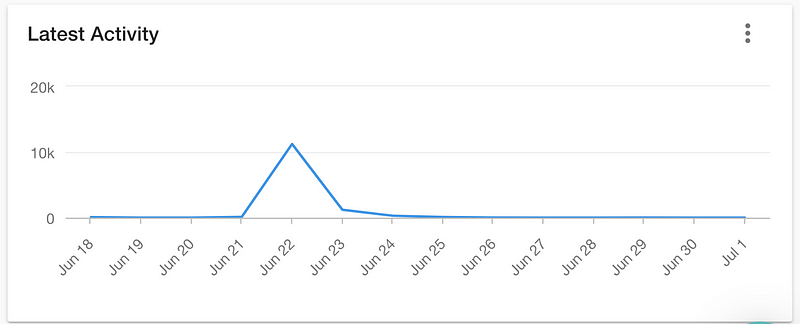

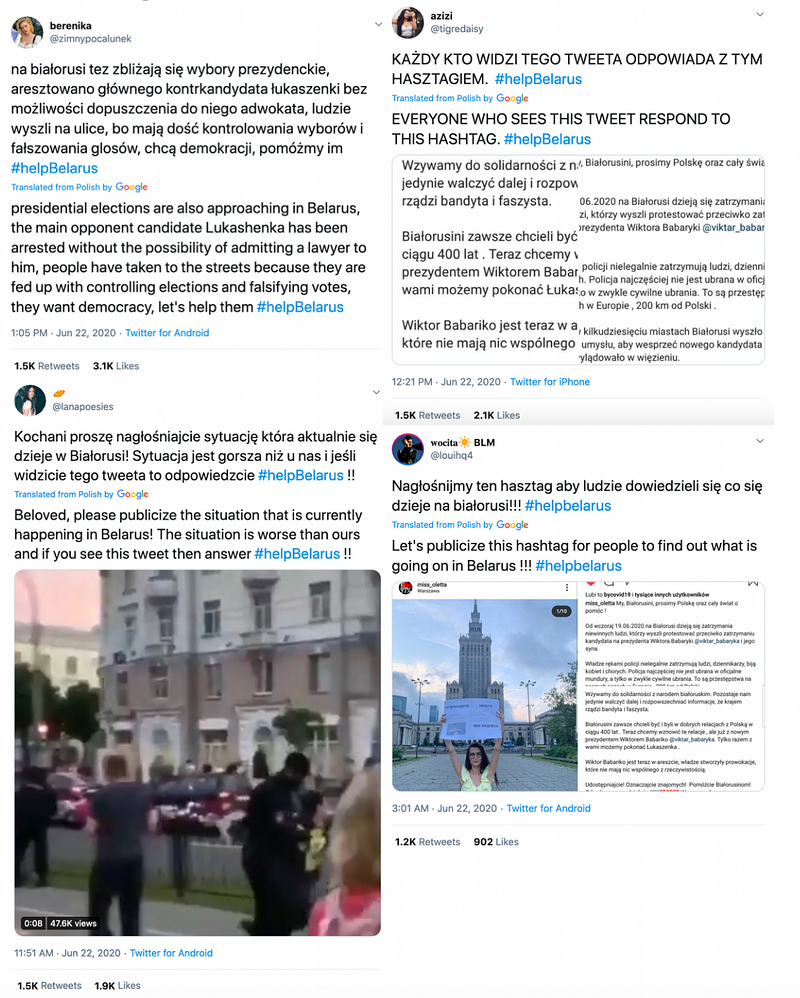

On June 22, the #helpBelarus hashtag began trending on Twitter.

The most retweeted tweets called on raising awareness about the situation in Belarus by amplifying the hashtag. Most tweets came from accounts with their locations set to Poland.

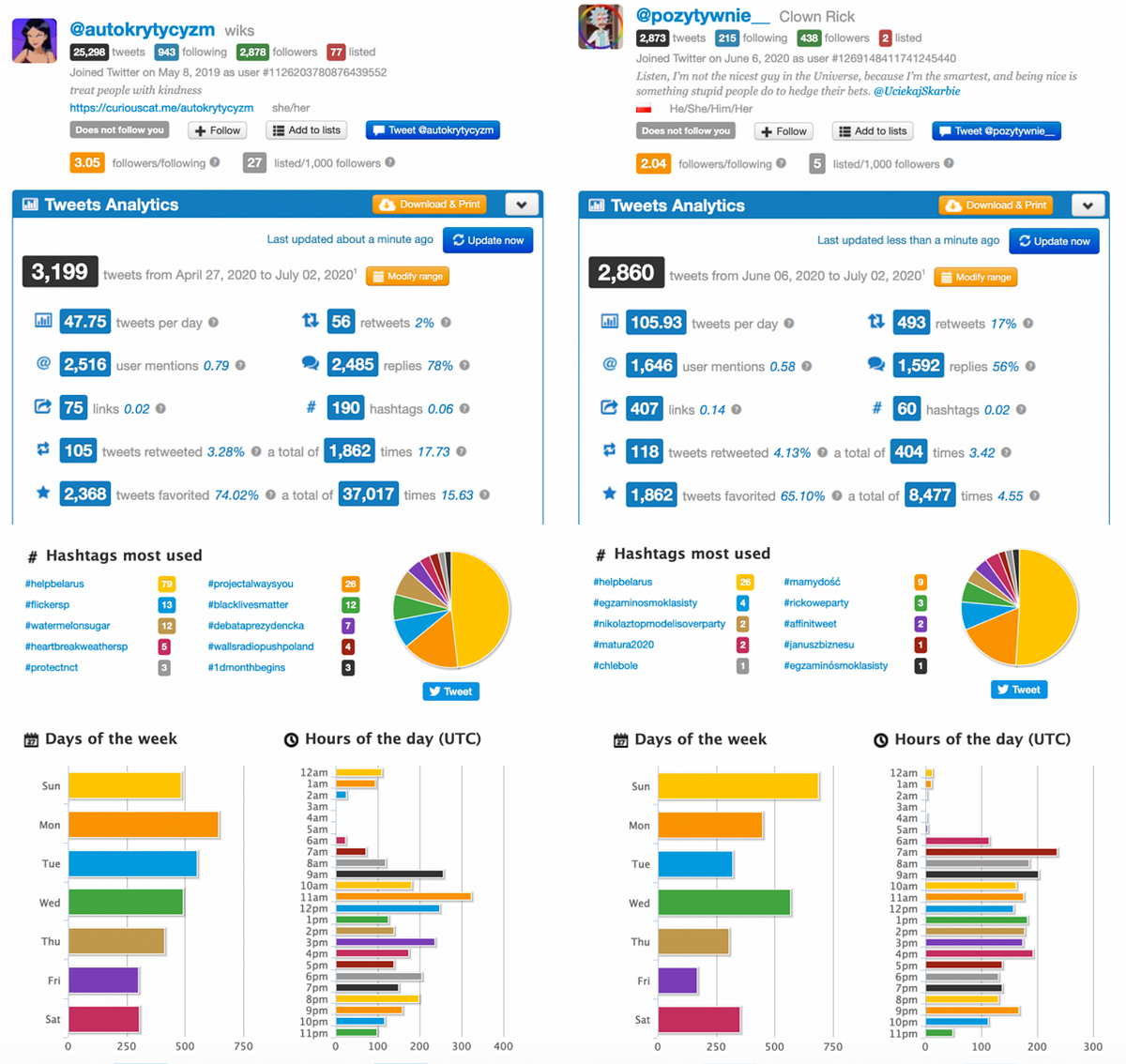

The two most active Twitter accounts using the hashtag were @autokrytycyzm and @pozytywnie__. Both mentioned the hashtag 80 and 72 times, respectively, which accounted for only 0.05 percent of all of the tweets from Polish accounts using the hashtag. This suggests that a small number of hyperactive users were not responsible for making the hashtag trend, a tactic often observed in inorganic Twitter traffic flows.

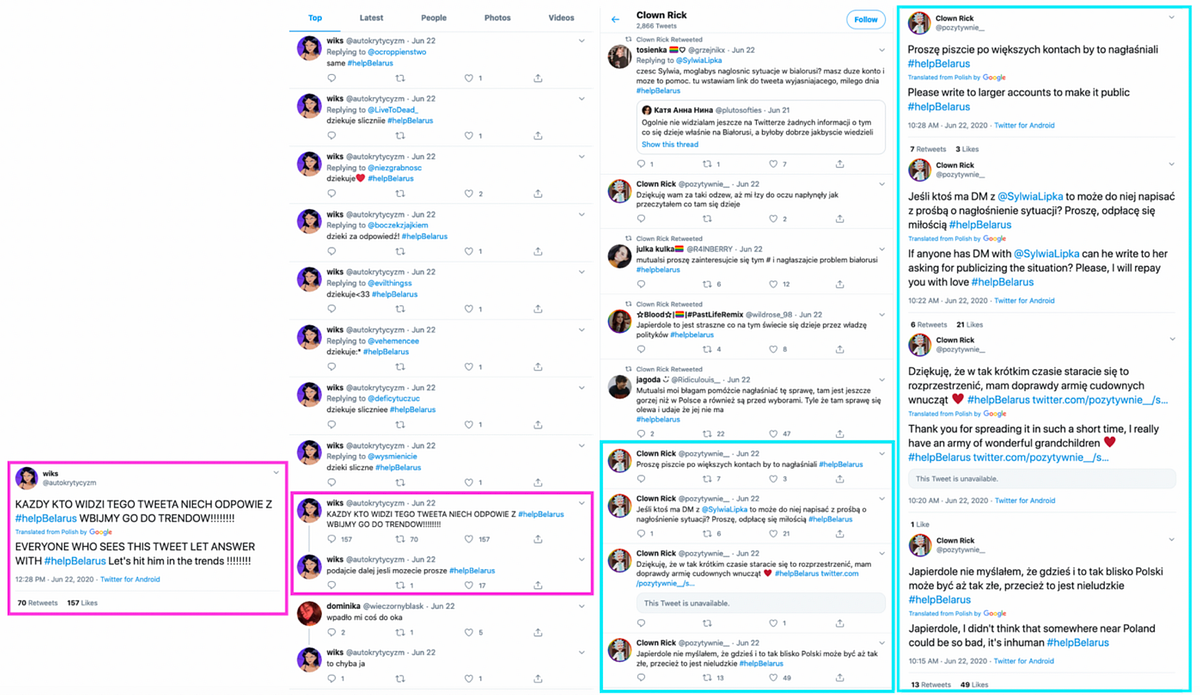

Nevertheless, both accounts behaved as amplifiers of the hashtag. Below is an example of their timelines on June 22.

For example, @autokrytycyzm suggested its followers to use the hashtag #helpBelarus in replies to make it trend on Twittter. In another Polish tweet, @pozytywnie__ in implied that he mobilized his followers to use the hashtag.

Both Twitter accounts used cartoon avatars for their profiles and were anonymous. They also produced many tweets per day — @autokrytycyzm posted an average of 47.75 times a day over a three-month period, while @pozytywnie__ posted an average of 105.93 times a day in just under a month. Nevertheless, both accounts mostly engaged in Twitter conversations in which they interacted with other users, suggesting that their operators were human users. They also did not tweet through the night in Poland or engage in consistent 24/7 activity, which is often a hallmark of inauthentic accounts.

The accounts engaged with other hashtags involving political and social issues, including #blacklivesmatter — but they consistently did so in Polish, increasing the likelihood of their authenticity.

Solidarity rallies across Europe

In the case of Polish accounts tweeting about #blacklivesmatter, it is critical to not underestimate the potential scale of authentic coordinated civic action and solidarity. This is especially true for an issue that is increasingly salient across the globe. Black Lives Matter protests have swept across multiple cities in the Balkans and Central Europe, including the Polish capital of Warsaw.

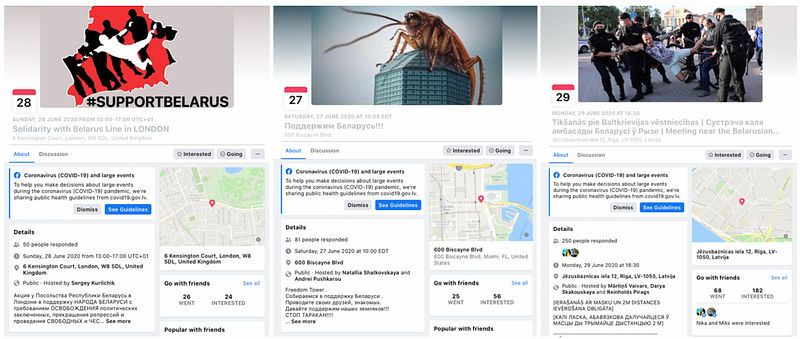

In a similar manner, multiple cities on both sides of the Atlantic held solidarity protests with Belarusian citizens. The DFRLab identified and geolocated 23 solidarity protests against political repression in Belarus that took place from June 19 in Kiev to July 1 in Brussels. At least six of these solidarity events took place in the United States.

https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1ORudv_fgGdoYF1IfejSuicy0iWAReM4l

The DFRLab examined the organizers of these events. In most cases, the organizers were members of the Belarusian diaspora. Some of them had expressed criticism of Lukashenko before, like a co-organizer of a solidarity protest in Florida. Others, like the co-organizer of an event in San Diego, did not have a history of posting political content, but appeared to be spurred to political action by the situation in Belarus. The visual identities of the Facebook events, event descriptions, and banners were distinct, and the protests actually took place. There was no indication that they were fake or organized by nefarious actors using astroturfing techniques to create the false impression of grassroots support.

As domestic dissatisfaction with President Lukashenko’s government bubbled over in Belarus, Lukashenko turned to a common scapegoat for political leaders with an authoritarian streak: foreign interference. In particular, Lukashenko alleged that Russia was meddling in the upcoming Belarusian elections by way of Poland. One of the indicators of this alleged foreign interference was the large number of Polish accounts posting on Twitter expressing solidarity with Belarusians, as well as a number of solidarity protest events on Facebook organized throughout the world. Yet the origin and nature of these online activities show no indication of foreign interference or nefarious activity. All of the evidence suggests that the wave of civic activism currently sweeping Belarus are grassroots movements steered by Belarusian civil society members and those standing in solidarity with them — whether President Lukashenko likes it or not.

Nika Aleksejeva is a Research Associate, Baltics, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.