Georgian far-right Facebook pages and their stance toward Russia

Far-right groups are not homogenous in

Georgian far-right Facebook pages and their stance toward Russia

Far-right groups are not homogenous in terms of their sentiment toward Russia

This story was published in partnership with On.ge. სტატია ვრცლად წაიკითხეთ აქ.

Over the last four years, domestic far-right actors have gained increasing prominence in Georgia. Ahead of the upcoming parliamentary election in October 2020, there has been heightened concern that the Kremlin may attempt to mobilize these groups in an effort to exert its influence on political processes in the country. The concern is not hypothetical — several studies have noted the ideological convergence of the Kremlin with far-right groups in Western liberal democracies, as well as the possible institutional and financial support provided to these groups by the Kremlin.

The DFRLab conducted a social media content analysis of several Georgian far-right Facebook pages in order to examine their attitudes and discourse toward Russia. The results showed that these groups are not homogenous in terms of their sentiment toward Russia, instead expressing a range of opinions, from open support of the Kremlin to active hostitlity. This finding supports the conclusions of a recent study from the the Political Capital Institute that distinguished three different categories of far-right groups in Eastern Europe according to their stance toward Russia: committed groups, open groups, and outwardly hostile groups. The third category was especially prevelant in countries in open conflict with Russia. In the case of Georgia, Russia’s ongoing occupation of Georgian territories appears to have fomented a distinctly nationalist strain of far-right discourse that maintains — at least publicly — an anti-Russia stance.

Methodology and dataset

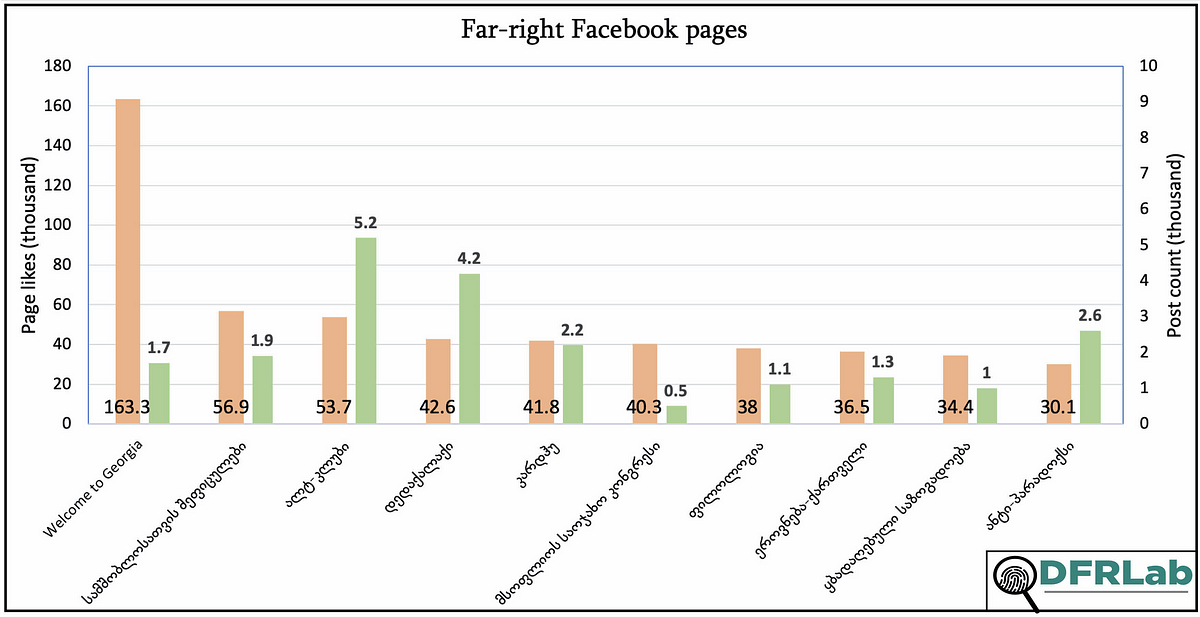

Using the social media monitoring tool CrowdTangle, DFRLab collected 21,740 Facebook posts published between January 1, 2018 and July 15, 2020 by 10 far-right Facebook pages with the highest number of followers. These 10 pages were selected from roughly 50 active far-right pages included in the Disinfo Observer database, as well as in previous studies conducted by the EPRC and the Democracy Research Institute.

The total number of page likes of the selected 10 pages exceeded 500,000 as of July 15, 2020, and the vast majority of them have steadily grown their audiences over time.

Of the 21,740 Facebook posts published by them in the selected time period, a total of 671 posts contained terms related to Russia, including “Russia,” “Kremlin,” “Putin,” and “Moscow” keywords in various conjugative forms in Georgian. They were subsequently manually coded in line with three specific characteristics: the author’s sentiment toward Russia (negative, neutral, or positive), the themes they addressed, and the countries they mentioned.

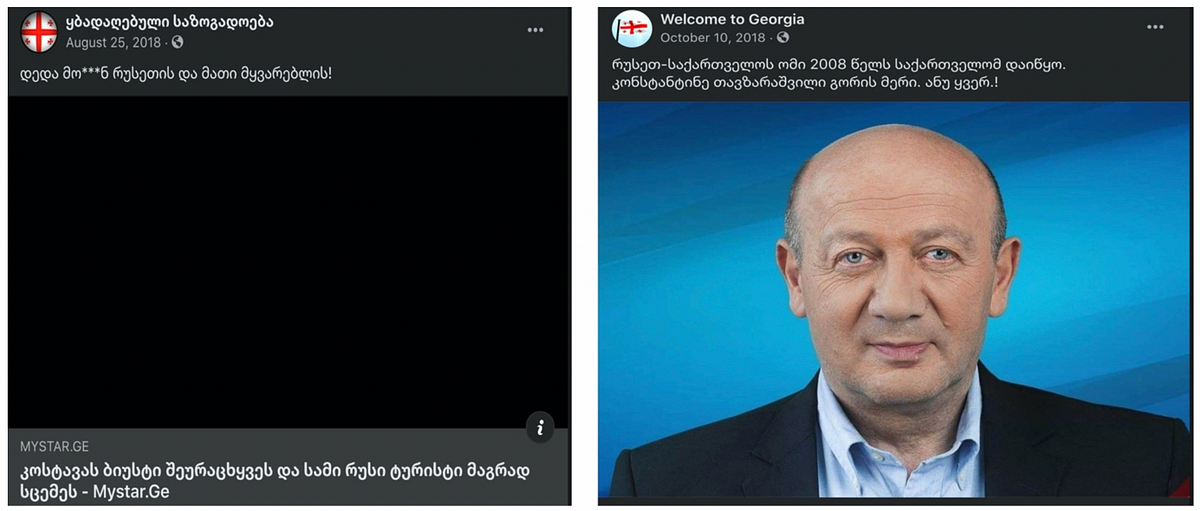

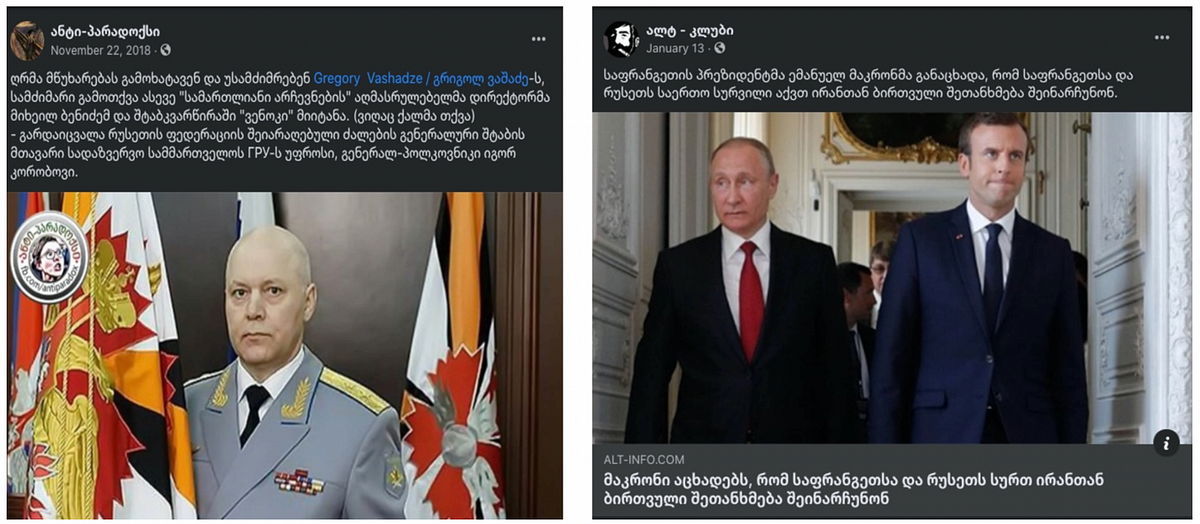

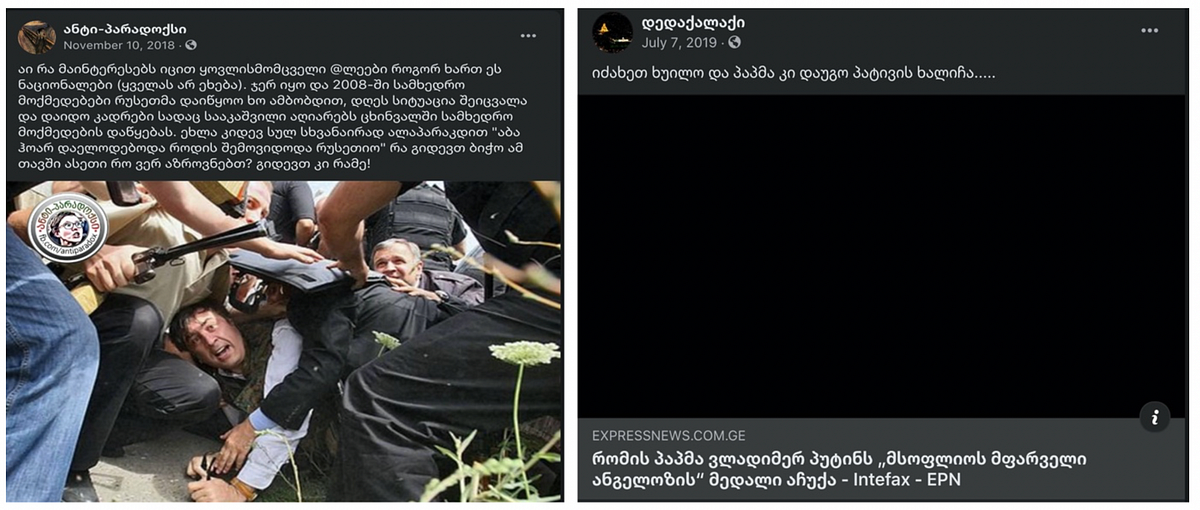

Some examples of how the DFRLab coded the selected posts:

· Page ალტ-კლუბი: ”We must remember it! As a result of Russian aggression, 170 staff of Ministry of Defence of Georgia have died, 14 staff of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia and 224 civilians. Russia occupied 20% of Georgia’s territory” — Negative, 2008 War, Russia and Georgia.

· Page დედაქალაქი: “Now someone will say Russia again… Look at how big articles in popular Russian newspapers are dedicated to Epiphany, whereas our ‘media’ did not go beyond the transgender topic” — Positive, LGBT and religion, Russia and Georgia.

· Page ალტ-კლუბი: “Putin and Erdogan agreed on ceasefire in Syria’s Idlib province” — Neutral, international politics, Russia and Turkey.

Topical analysis

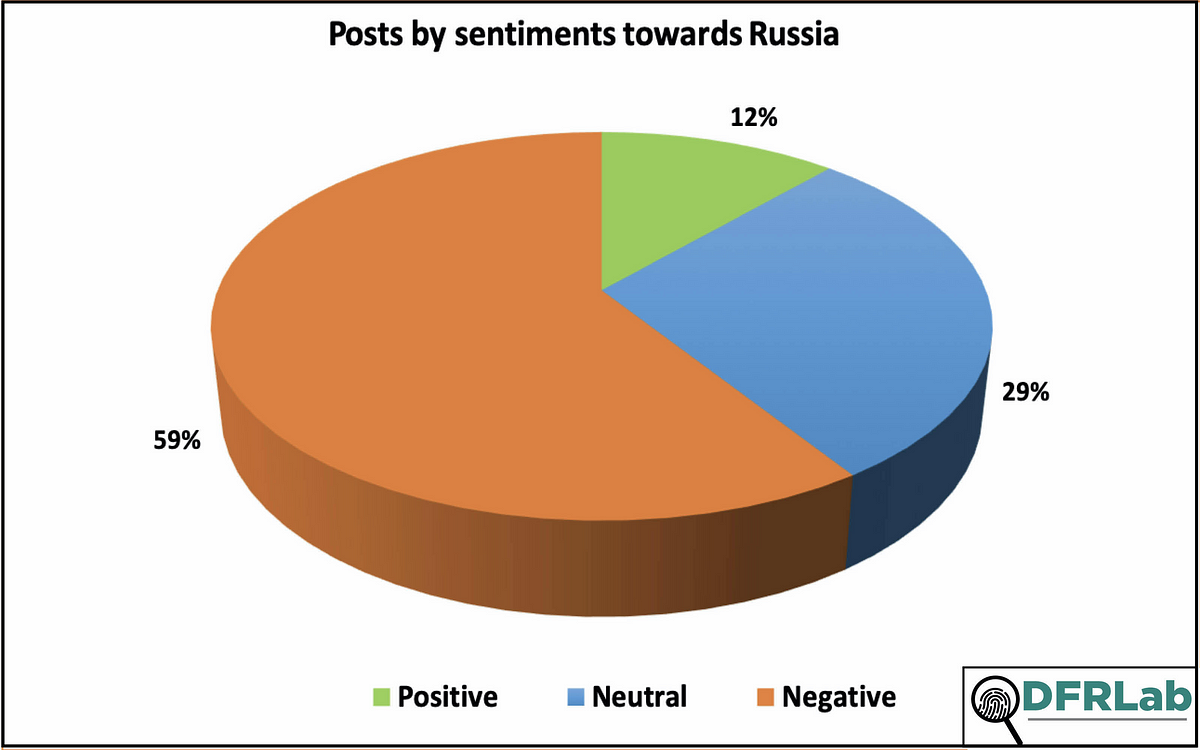

Although the selected far-right groups all pushed anti-liberal narratives and some of the posts depicted Russia in a positive light, almost 60 percent of the analyzed posts (398) exhibited negative attitudes toward Russia, mostly involving criticism and disapproval of Russia’s actions toward Georgia. Slightly below one-third of them (194) were written in a neutral tone, meaning they did not convey a clearly positive or negative stance about Russia. Lastly, 12 percent of the posts (79) registered a positive tone toward Russia, portraying its actions in a positive light.

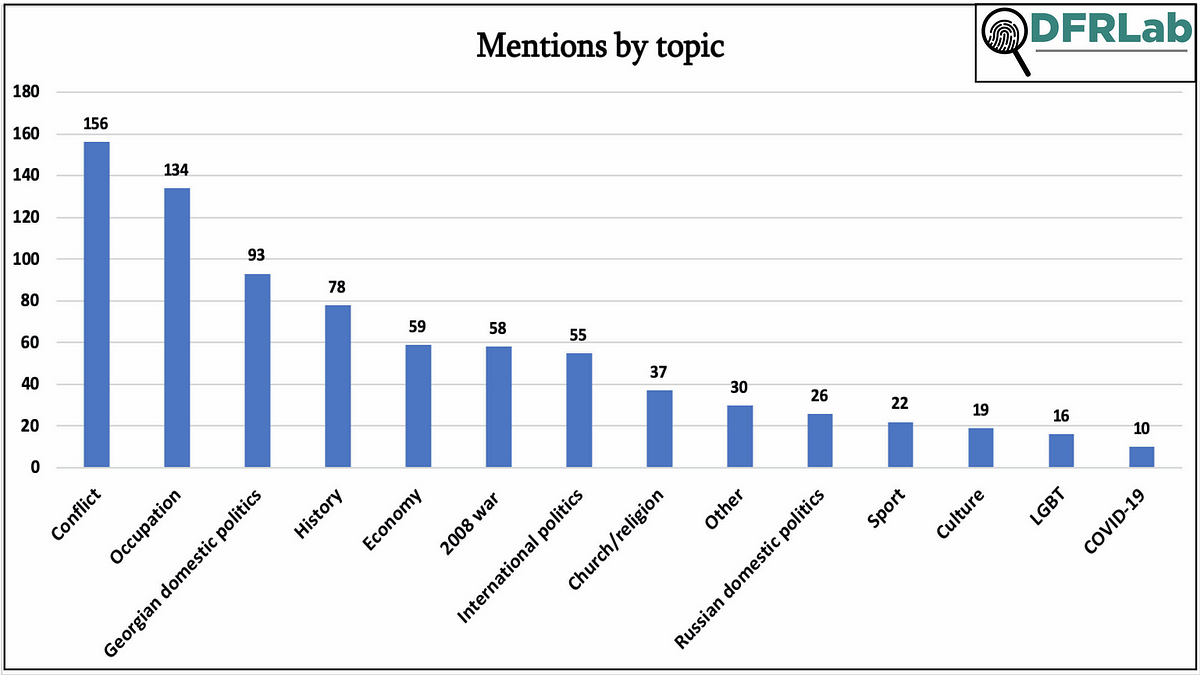

The DFRLab also identified 13 topics mentioned most often in the context of Russia by these pages; most concerned Georgia-Russia relations. Since the occupation of Georgian territories by Russia and the 2008 war remain the two primary sources of tension between the countries, the DFRLab decided to separate these two topics from the more general category of conflict and count their mentions.

The pages mentioned other topics, such as sports, culture, and religion, considerably less frequently. However, when they did mention them, they frequently used the topic of Russia to criticize Georgia’s previous government and to disparage liberal figures. Some posts mentioned more than one topic; and in those cases, all topics were recorded.

Russia’s occupation of Georgian terrorites was a primary topic of concern for Georgian far-right groups. This finding makes sense given the political context in which many of these groups emerged. A recent Freedom House report noted that far-right movements in Georgia and Ukraine became more prominent following the 2008 war and the annexation of Crimea.

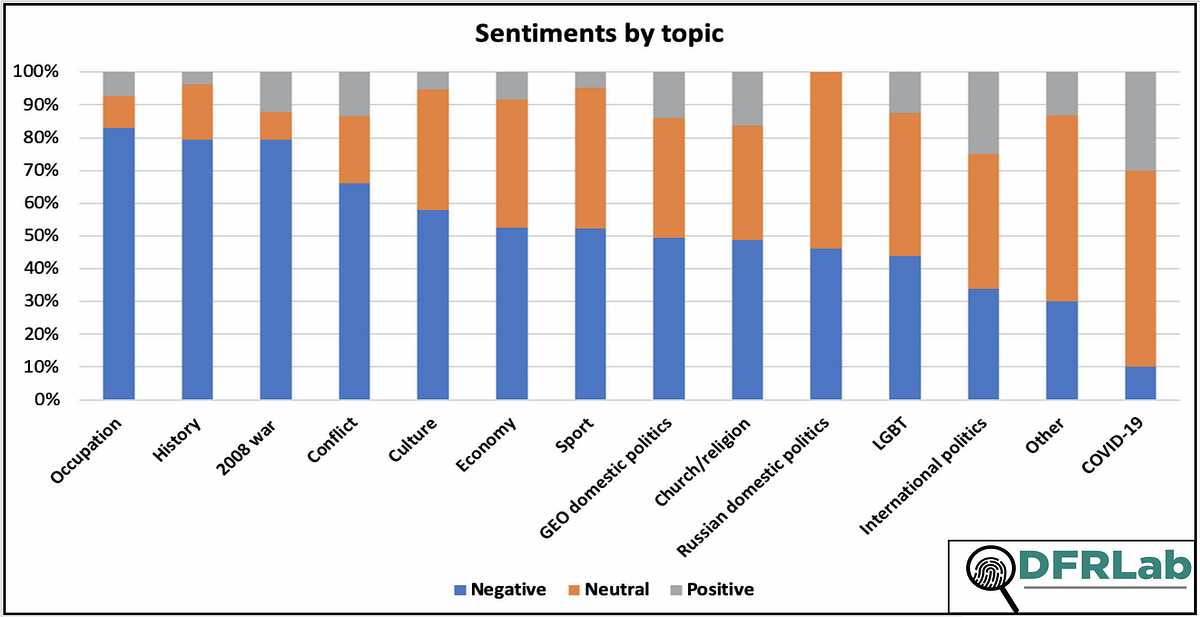

Further sentiment analysis revealed that the 2008 war is not the only topic driving negative sentiment contributing to anti-Russia discourse among Georgian far-right groups. Discussions related to Georgia’s prior history, particularly the 1992 Abkhazia war and Russia’s role in it, triggered almost as much negative sentiment toward Russia as the topic of occupation.

Non-political topics the DFRLab analyzed, such as culture, economy, and sports, also showed mentions loaded with negative sentiment, which may indicate that for far-right groups, these fields are also politicized. Interestingly, the topic of LGBT rights — on which both far-right groups and the Kremlin tend to be in agreement — evoked little positive sentiment as far as Russia was concerned. Lastly, Russia’s activities in international politics evoked less negative sentiment than neutral sentiment.

Negative sentiment

Georgian far-right groups frequently praised the leaders of the Georgian dissident movement from the 1990s who fought for Georgia’s independence, and some posts accused Russia of plotting the mysterious deaths of these leaders. Another trend the DFRLab observed was that, although the majority of the far-right groups under analysis accused Russia of invading Georgia in 2008, they also criticized Georgia’s previous government for not being wise enough to avoid escalation of the conflict that resulted in military clashes. The DFRLab found that over 40 percent of posts with negative attitudes toward Russia were related to occupation, the 2008 war, and other aspects of Russia-Georgia conflict. At the same time, the groups seemed to be divided over the topic of conflict resolution. Indeed, whereas some did not support political dialogue between Georgia and Russia, others saw it as the best option to normalize relations between the two countries.

Neutral sentiment

Georgian far-right groups exhibited a relatively neutral tone when writing about Russian domestic politics or internal developments that did not involve Georgia. At the same time, the topic of Russia’s internal affairs was not a prominent one, and only events of international concern (e.g. rccent constitutional amendments, Prime Minister Mishustin being infected by COVID-19) were typically covered. Far-right pages actively advocated for a so-called “pro-Georgian” course, calling for Georgia to rely on itself and balance its relations with the West and Russia. This position is somewhat in line with Russia’s interests, however, as it obstructs Georgia’s full integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions, a priority enshrined in Chapter 11 of Georgia’s constitution.

The analyzed pages repeatedly denounced Georgia’s former President Mikheil Saakashvili and his administration for their liberal-democratic reforms. Interestingly enough, they also accuse them of maintaining close links to Russia in spite of publicly posing as the Kremlin’s harshest critics.

Positive sentiment

Every topic analyzed presented Russia in a predominantly negative or, less often, neutral light. Two topics that evoked the highest volume of positive sentiment, however, were COVID-19 and Russia’s role in international politics.

A small number of posts put the blame for starting the 2008 war with Russia on Georgia. Since this narrative served the purpose of whitewashing the Kremlin’s actions, the DFRLab coded it as conveying a positive tone toward Russia. Some posts further suggested that only the Kremlin can guarantee peace and Georgia’s territorial integrity, while others criticized the Georgian political establishment for its repeated use of the Russian threat to explain domestic problems in Georgia. Along similar lines, some posts dismissed the existence of malign intentions on the part of Kremlin leadership toward Georgia and accused some unidentified forces of deliberately damaging the relationship between the two countries. Nevertheless, the overall number of positive sentiments was almost five times fewer than negative sentiments.

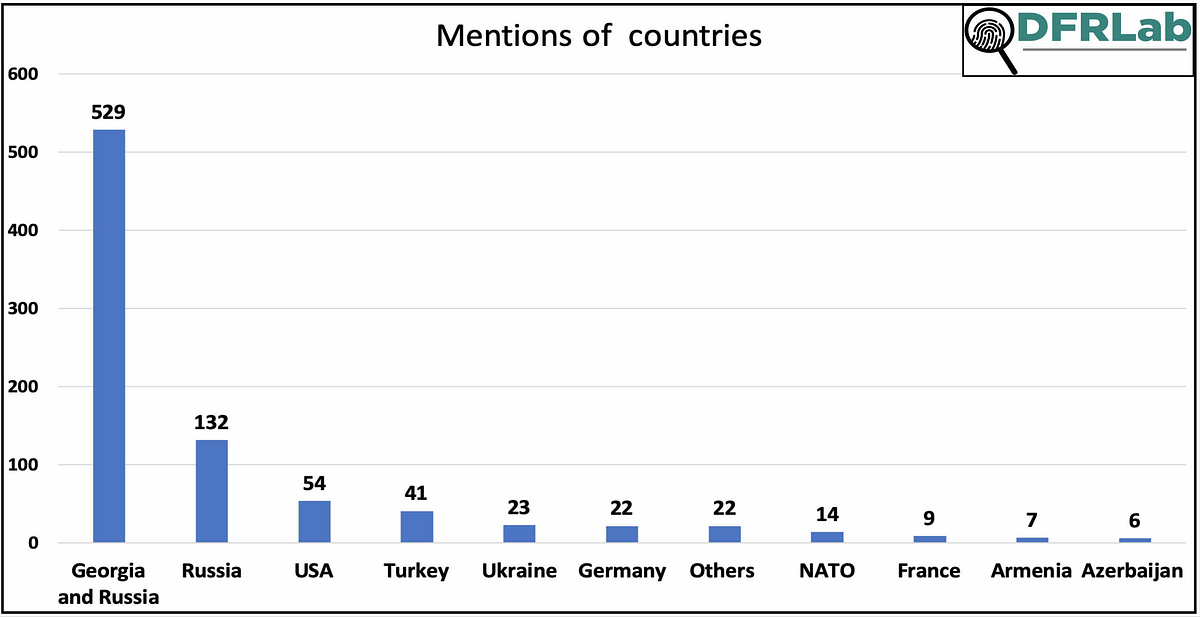

Mentions of countries

A number of posts aimed to revive the Georgian public’s skepticism toward the country’s Western allies — most importantly, the United States. They argued that, should Georgia become a target of Russian aggression yet again, none of Georgia’s Western allies would come to the country’s defense. The example of Ukraine was sometimes used to support this point. Some of the far-right pages studied also presented Turkey in a negative light, portraying it as an unfriendly, dangerous enemy of Georgia on par with Russia. The DFRLab has previously reported that pro-Kremlin Russian media outlets pushed hostile narratives about Turkish-Georgian relations that were then amplified by Georgian actors. In terms of the overall count of country mentions, the analysis showed that the majority of posts mentioned both Georgia and Russia together, whereas around one-fifth of posts did not include content about Georgia, mentioning Russia and other countries.

Conclusion

Georgian far-right groups actively use social media platforms to push forward their anti-liberal and anti-West agenda in the country. These groups’ interests converge with those of the Kremlin on several fronts: they both condemn liberalism and advocate “traditional values,” as well as employ harsh rhetoric toward champions of socially progressive reforms in Georgia. Lastly, they are critical of Georgia’s Western allies, who support the country’s territorial integrity and provide significant assistance, financial and otherwise.

A content analysis of posts by far-right Georgian far-right Facebook pages, however, showed that these pages’ public stance toward Russia was mixed. While some pages overtly supported the Kremlin, a significant segment routinely criticized Russia and portrayed it as a foe rather than a friend. This may suggest that the attitudes of Georgian far-right groups toward Russia are more heterogenous than they are often portrayed. Russia’s occupation of Georgia, as well as several other historial points of tension in Georgia-Russia relations, has perhaps led some far-right actors to adopt a more nationalist, pro-Georgia stance, despite some ideological overlap with the Kremlin on attitutes toward the West. At the same time, it is worth mentioning that this study did not involve an analysis of the motivations of these far-right actors, and further research should explore whether these groups are genuine in their criticism of Russia or whether they are merely attempting to capitalize on anti-Russian sentiment among the Georgian public.

Givi Gigitashvili is Research Assistant, Caucasus, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in Georgia.

This research is part of the #ElectionWatch Georgia project in partnership with On.ge, made possible through support from East-West Management Institute (EWMI) and US Agency for International Development (USAID). Contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EWMI, USAID or US Government.