Xenophobic Twitter campaigns orchestrated by former South African soldier

A dismissed member of the South

Xenophobic Twitter campaigns orchestrated by former South African soldier

A dismissed member of the South African National Defence Force has been gaming Twitter’s algorithms to foment xenophobic violence

Sifiso Jeffrey Gwala, a former lance corporal with the 121st SA Infantry Battalion in Mtubatuba in coastal KwaZulu-Natal, has been identified as the person behind the “anonymous” Twitter account previously known as @uLerato_pillay, which has been accused of inciting xenophobic tensions in South Africa. In recent weeks, these narratives have bubbled to the surface of mainstream media outlets as public officials from fringe political parties echoed these nationalist sentiments in what appears to be reckless political opportunism.

South Africa has a fatal history of violence against foreign nationals, particularly other Africans. In May 2008, 62 people died as a result of nationwide xenophobic riots that started near Johannesburg, and in April 2015, seven people were killed in similar protests in Durban. South Africa’s high unemployment rate and lackluster service delivery is often blamed on the nearly 4 million foreign nationals staying in South Africa, and unfounded claims that foreign nationals are disproportionally responsible for crime are frequently used to justify these attacks.

As recently as July 30, 2020, communities in Thokoza, south of Johannesburg, forcefully evicted foreign nationals from their homes and burned their possessions in the street. A march to “cleanse” Johannesburg of foreign nationals on September 23 has been orchestrated and amplified by #PutSouthAfricansFirst, a movement that coalesced around Gwala’s online persona.

In this setting, Gwala used the @uLerato_pillay account to sic his more than 60,000 followers against foreign nationals and refugees living in South Africa, usually under the guise of one of several nationalist pro-South African hashtags.

Background

The @uLerato_pillay account was the focus of a DFRLab investigation published on July 3, 2020. Although that investigation correctly identified the name of the person behind the account as “Sfiso J Gwala,” it fell short of identifying a specific individual. In the time since that story was first published, @uLerato_pillay changed its account handle to @PutSAnsFirst_, and has apparently changed hands to a member of the South Africa First political party. Meanwhile, an entirely new account has laid claim to the @uaLerato_Pillay handle.

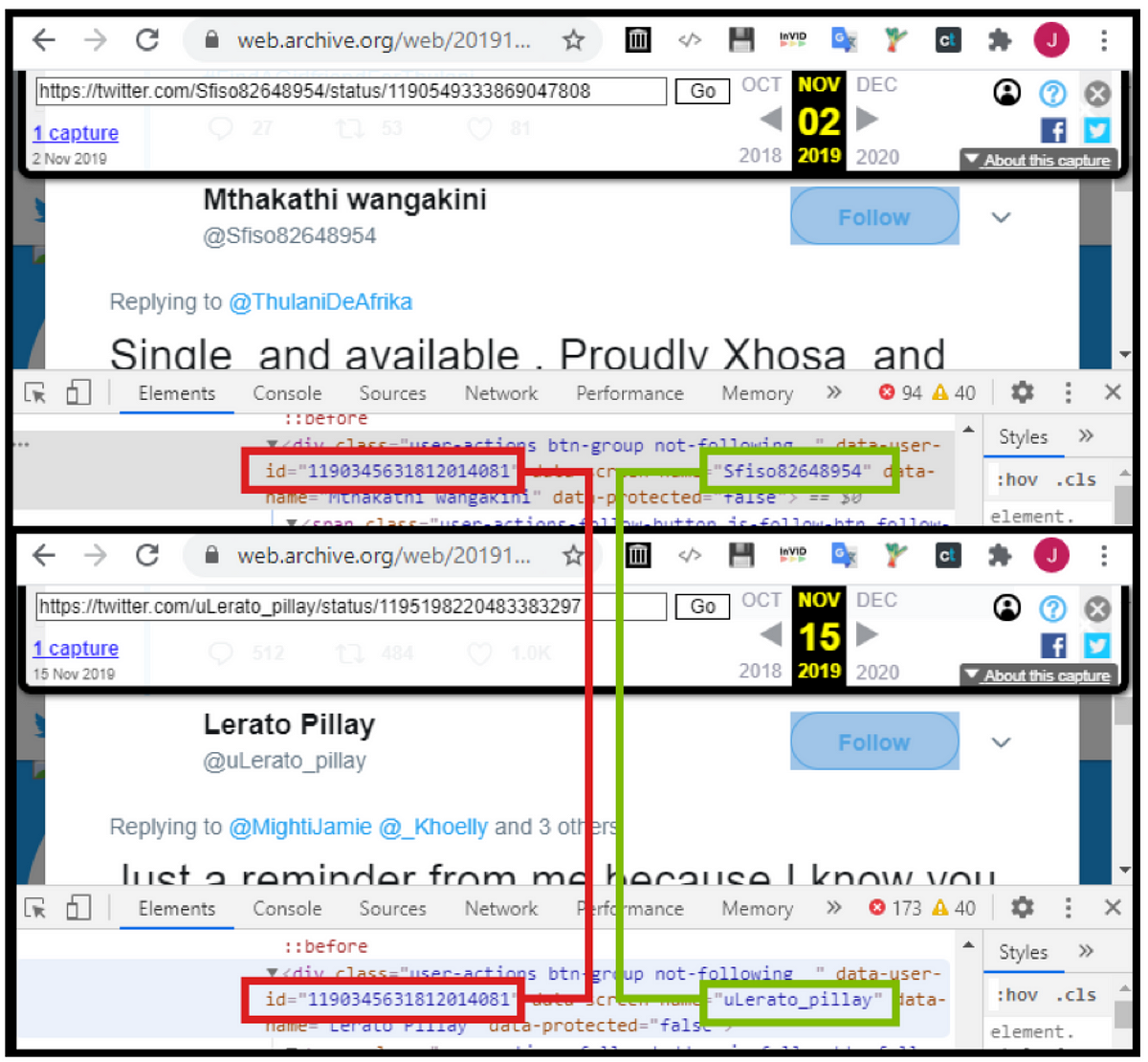

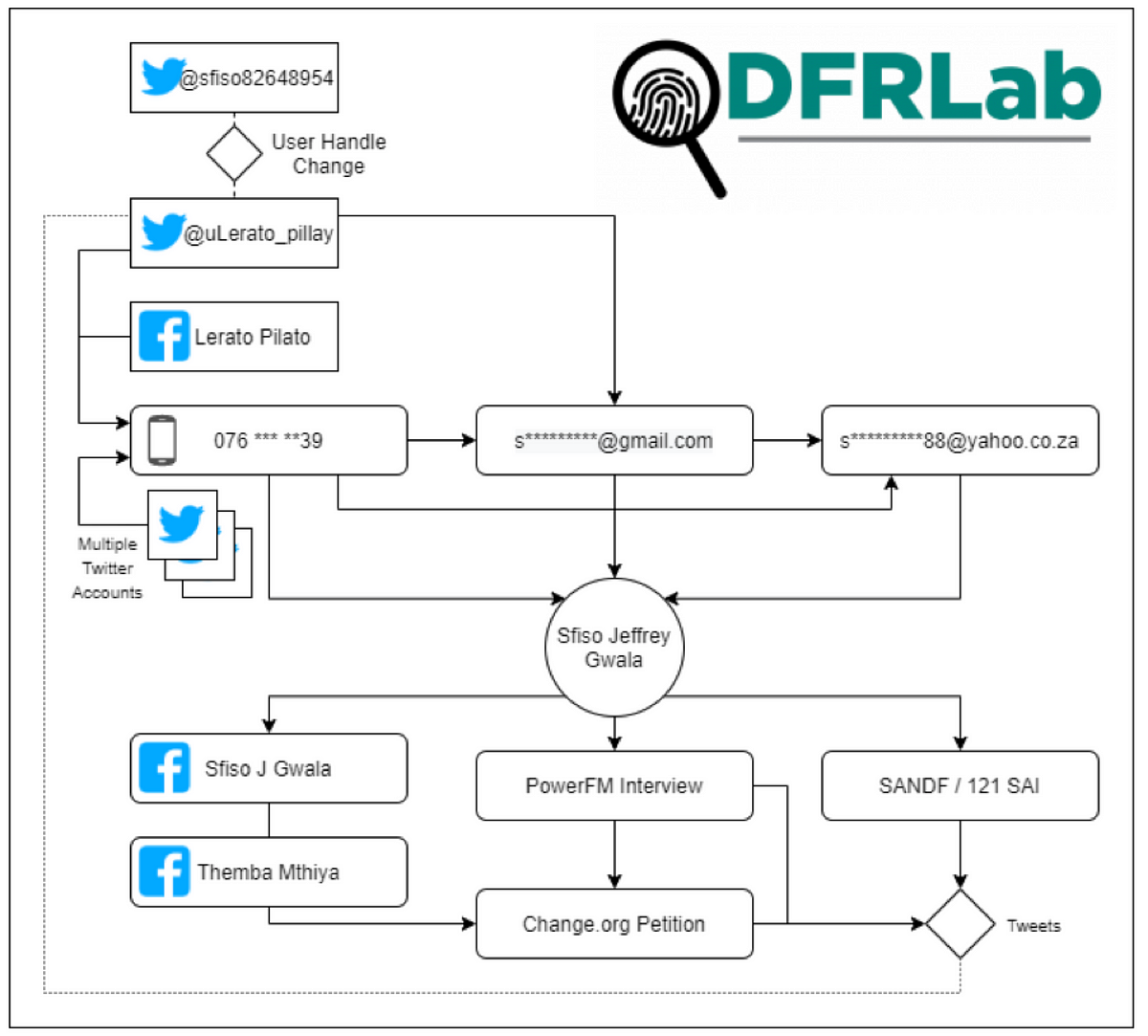

In the earlier investigation, the DFRLab found that after it was created on November 1, 2019 the @uLerato_pillay account was initially known as @sfiso82648954. The account only adopted the @uLerato_pillay persona — that of an Indian woman from Gwala’s home province of KwaZulu-Natal — sometime around November 6, 2019.

Cached and archived versions of the account as it appeared back then were used to confirm that both of these user handles belonged to the same Twitter user ID. Although a user can change its display name, user handle and profile images, the user ID cannot be changed.

This association was corroborated during the investigation with several interactions between @uLerato_pillay and another Twitter account called @sfisogwala_sa. The latter account claimed to be part of the South Africa First party, a fringe political movement with strong nationalist tendencies that features frequently on @uLerato_pillay’s timeline.

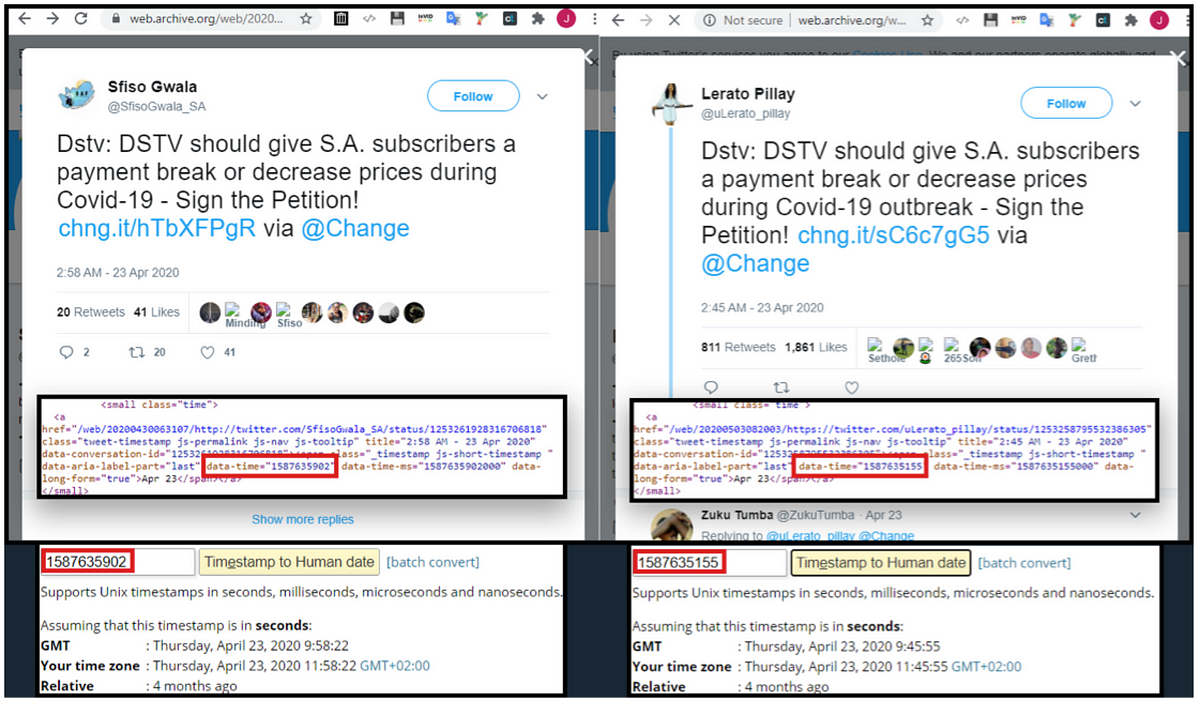

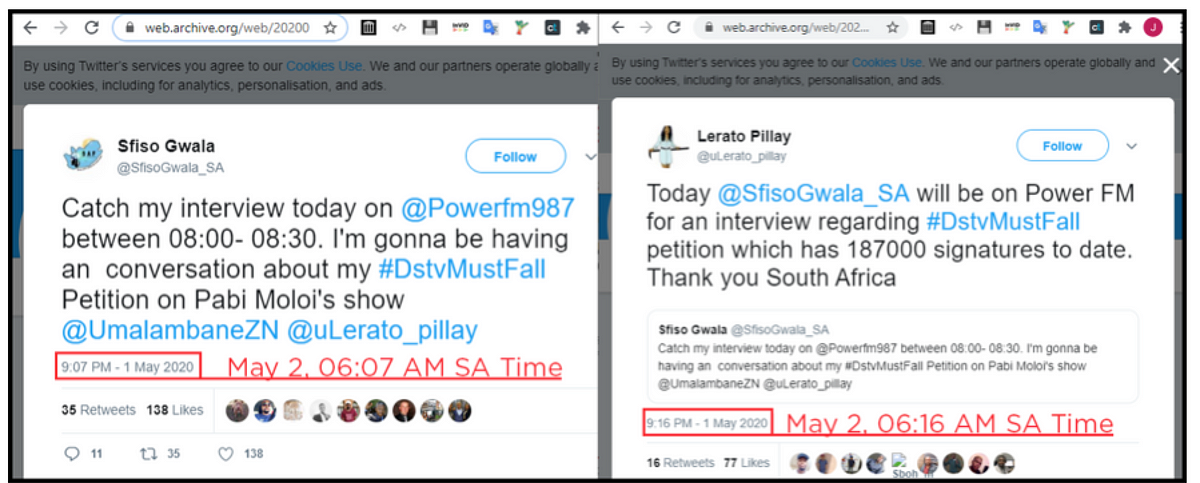

The investigation also linked Gwala to @uLerato_pillay through a Change.org petition created in late April 2020. The petition called on DStv, a South African satellite television provider, to drop their subscription prices in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The petition was created by a user called Sfiso J Gwala.

By comparing the source code of the Change.org website with the timestamps of the tweets from @uLerato_pillay and @sfisogwala_sa sharing a link to it, the DFRLab found that @uLerato_pillay shared a link to the petition 93 seconds after it was published by its creator at 11:44:23 A.M. local time. The @sfisogwala_sa account only shared a link to his “own” petition several minutes later.

Own goals

A week after this initial investigation, the DFRLab published an unrelated investigation into a different race-baiting Twitter account which drew significant traction in South Africa mainly due to the involvement of a member of South Africa’s third largest political party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) in monetizing the racist rhetoric churned out by the account.

The @uLerato_pillay account, seemingly unaware of the DFRLab’s investigation into its own identity, claimed credit for the investigation, and used the opportunity to label the EFF member at the center of the piece a foreign national.

Gwala’s lie was called out using his real name, and within seconds of being named “Sfiso” @uLerato_pillay deleted the tweet and blocked the DFRLab researcher that named him. Later that evening, @uLerato_pillay brigaded its followers to use the hashtag #HandsOffLeratoPillay in support of the “attack” against him.

This reaction stands in contrast to previous attempts to identify the owner of the account, which were met with disdain and ridicule from Gwala.

Further corroboration was soon found when a Facebook profile identified during the earlier investigation, called Sfiso J Gwala, was taken offline. While this Facebook account was identified during the previous investigation and was suspected of being the creator of the Change.org petition, it was not included in publications as it could not be conclusively linked to either the @uLerato_pillay or the @sfisogwala_sa accounts, until now.

Running interference

Within hours after the earlier DFRLab investigation was syndicated by local news publication Daily Maverick, attempts were made to destroy key evidence linking Gwala and the @uLerato_pillay account.

First, the Sfiso J Gwala Facebook account identified earlier was either deactivated or made private and could no longer be found when searching for either the username or the Facebook user ID of the account. The date of this is undetermined, but it was first noticed on July 11.

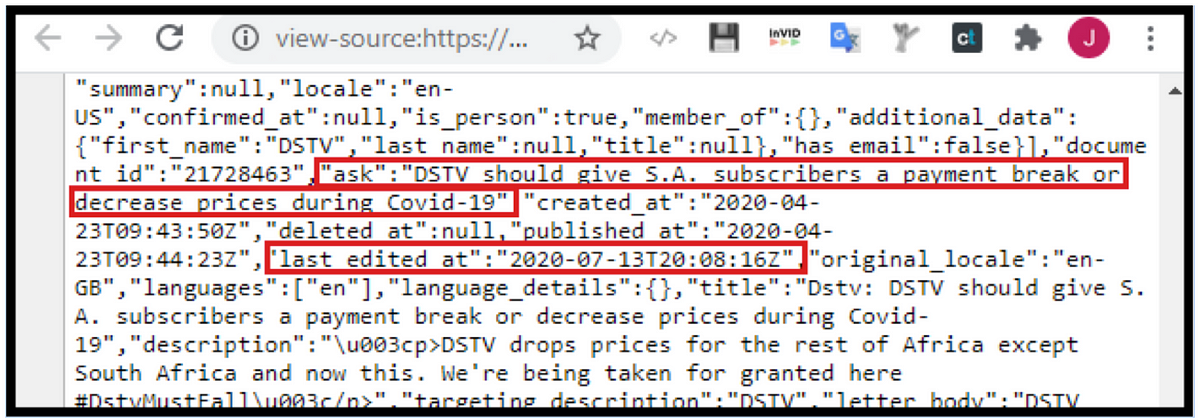

Second, the author of the DSTV petition attempted to close and delete the petition later on the same evening — peculiar timing considering that months had passed with no new updates. The Change.org page source code shows that changes were made at 10:08 P.M. local time on July 13, 2020.

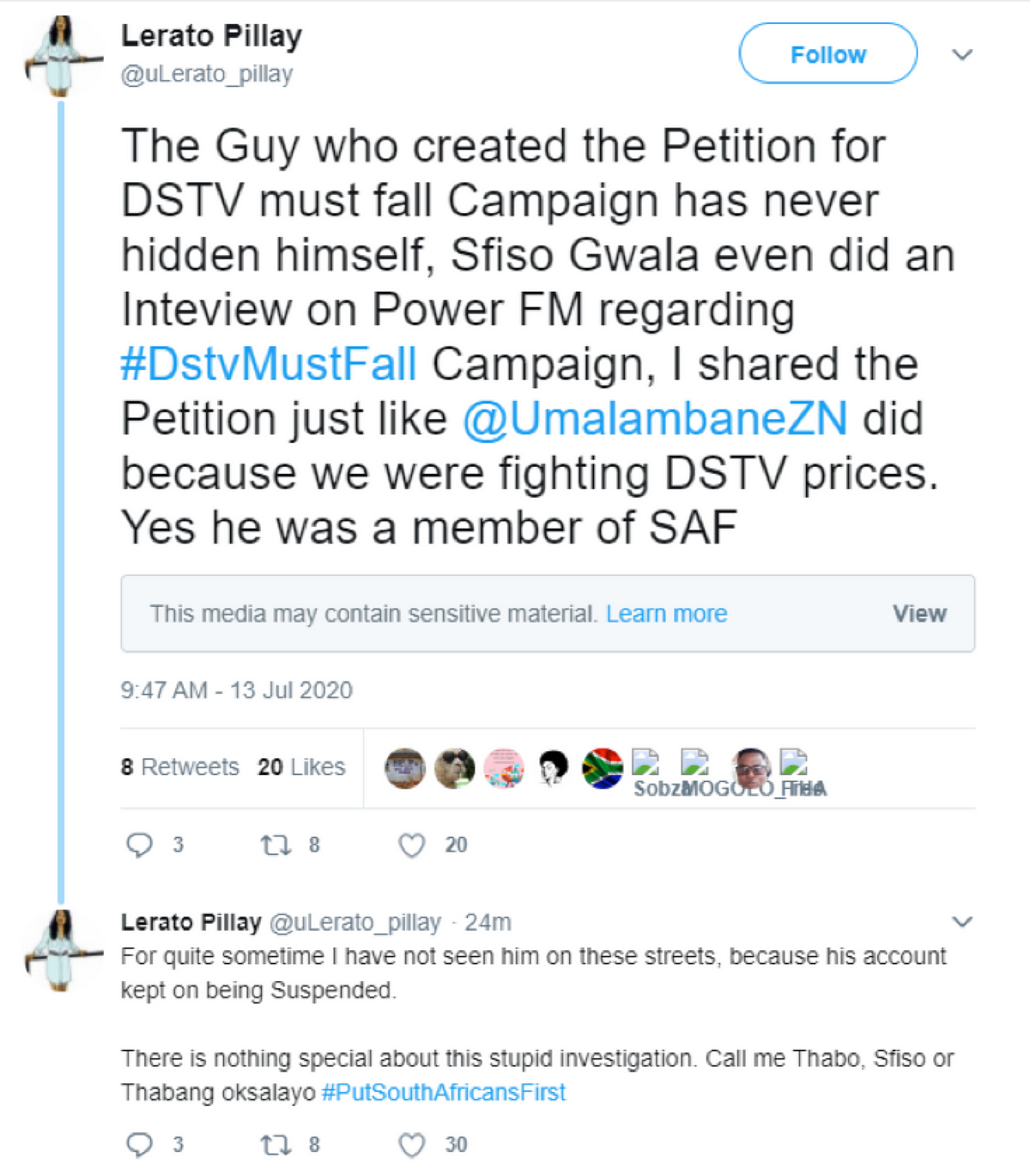

Lastly, the @uLerato_pillay account tweeted at 6:47 P.M. local time on July 13, 2020, in an attempt to distance itself from Sfiso Gwala. This tweet not only displayed intimate knowledge of Gwala’s suspended accounts (who’s only known personal account was suspended months earlier) and political affiliations, but also claimed that Gwala had never hidden his identity. The tweet was later deleted, although archived copies are still available.

Around the same time, the name of the creator of the DStv petition changed. Archived versions of the original petition show that Sfiso J Gwala created the petition, whereas a more recent visit to the petition now shows that “Themba Mthiya” is the creator.

But a review of the Change.org webpage source code shows that this was still the same user account. Both Themba Mthiya and Sfiso J Gwala share the same Change.org user ID, as evidenced when comparing the archived version of the page with the current version of the page.

This also means that the Sfiso J Gwala Facebook account had been renamed to Themba Mthiya. Change.org uses a person’s Facebook credentials to authenticate its users: when creating or signing a petition, each user is required to link their Facebook account with Change.org. This means that when Sfiso J Gwala changed their name to Themba Mthiya, this change was reflected on the DStv petition and resulted in the name change.

The same “Themba Mthiya” also posted updates on the status of the petition on July 13, and was also only the second person to sign a different petition shared by the @uLerato_pillay account on May 1, 2020, which called for the mass deportation of foreign nationals from South Africa.

These attempts to hide or destroy evidence linking Gwala, the DStv petition and @uLerato_pillay stand in contrast to the claims the Gwala has never hidden his identity. The timing of these attempts shortly after the investigation, coupled with the earlier links between Gwala and @uLerato_pillay, suggested that the name of this individual was right on the mark.

Mayday Radio

The DFRLab tracked down the radio interview mentioned by @uLerato_pillay in his tweet of July 13. Gwala was interviewed about his DStv petition on Saturday, May 2, 2020, on the PowerFM breakfast show. The @uLerato_pillay account promoted the interview early on the morning of the broadcast.

Gwala ended the interview by directing listeners to his @SfisoGwala_SA Twitter account, but before that, he also made several statements that could be traced back to @uLerato_pillay.

First, Gwala stated that he was asked by a Twitter user called “Malambane” to create the petition. On April 22, 2020, the day before the petition was created, the @uLerato_pillay account raised the issue of DStv’s high prices during the COVID-19 outbreak with a Twitter user called @uMalumbaneZN. Second, Gwala stated at 03m40s that “the day before yesterday [April 30, 2020] we initiated another tag #DSTVMustFall.” According to an analysis using social media monitoring tool Brandwatch, the #DSTVMustFall hashtag during this time was most aggressively promoted by @uMalambaneZN and @uLerato_pillay. @SfisoGwala_SA was not among those that started or amplified this hashtag. Lastly, Gwala told the hosts that DStv, as a South African company, needed to prioritize South Africa for payment holidays. At 04:10, Gwala capped this off with “As they say, charity begins at home,” a phrase used verbatim by @uLerato_Pillay two days before the interview.

Individually, any of these statements could be dismissed. But taken into consideration with the rest of the evidence linking Gwala to @uLerato_pillay, this ever-expanding series of coincidences become ever more unlikely.

General indication

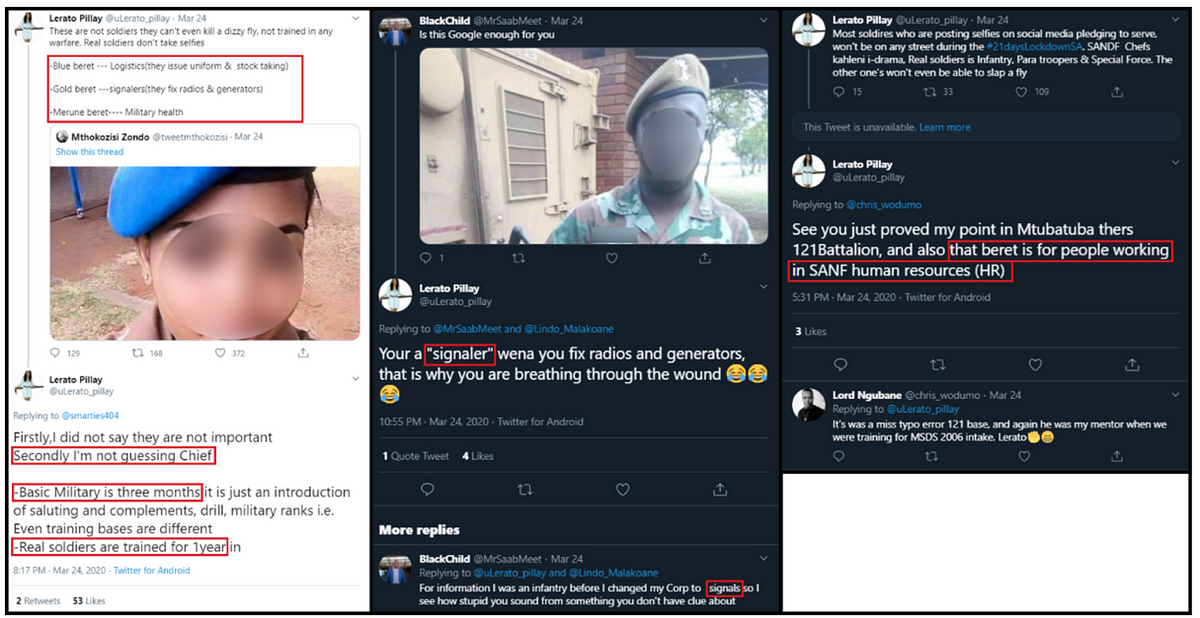

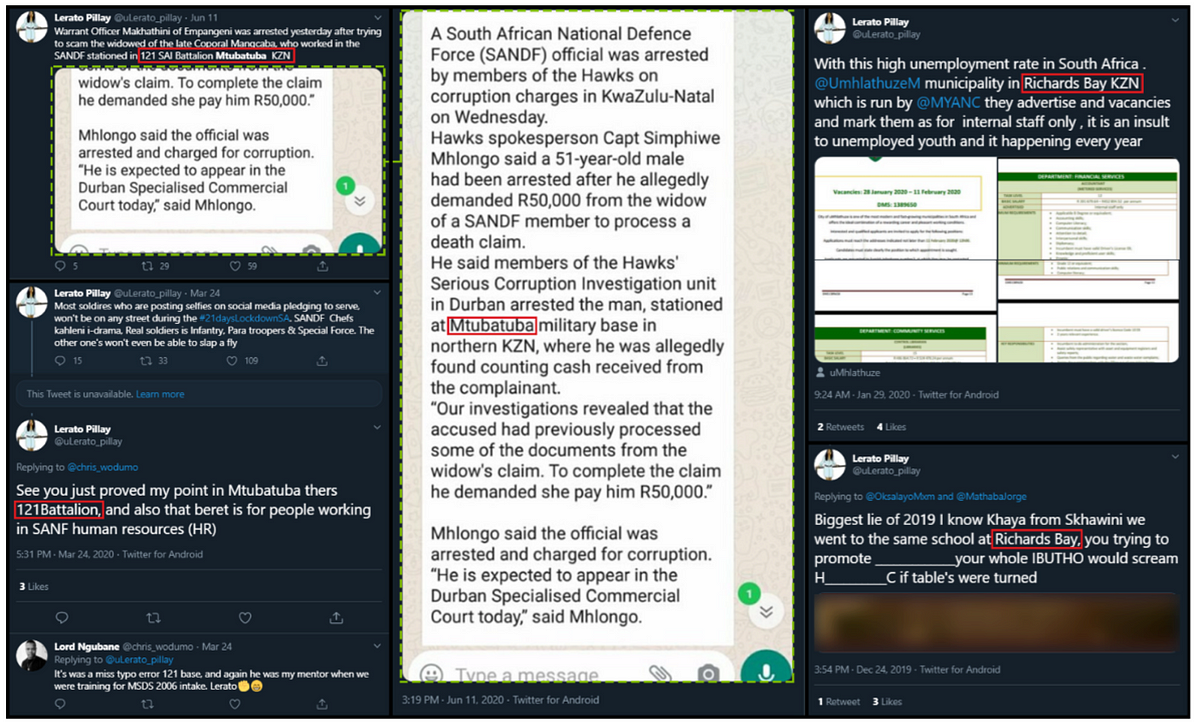

It was Gwala’s early tweets as @uLerato_pillay that identified his links to the South African military, and eventually led to confirmation of his identity. Examples of this could be found in tweets as far back as December 2019, which showed that the person behind the account had an excellent grasp of South African military culture, insignia, and deployments.

During March 2020, the SANDF was deployed to assist the South African government during the implementation of a nationwide lockdown in response to COVID-19. Several SANDF soldiers tweeted selfies of themselves during the deployment, to which @uLerato_pillay responded by correctly identifying their ranks and deployments based on their insignia and beret colors.

Other tweets praised the SANDF, particularly infantry and paratroopers, discussed their deployments and notable victories during peacekeeping missions, or displayed knowledge of their training regimens. The account also attempted to solicit a job for a “32 year old former SANDF driver” in one of its earliest tweets.

Corporal punishment

The earliest mention of the SANDF by @uLerato_pillay was in December 2019, when Gwala quoted a tweet from another anonymous influencer in reference to the SANDF.

Both tweets share a background. In 2015, the SANDF was deployment to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a joint United Nations peacekeeping force. Several SANDF soldiers part of this deployment were repatriated and eventually dismissed after they broke curfew and could not account for their whereabouts.

After this initial tweet, @uLeratoy_pillay tweeted about these soldiers and the state’s appeal proceedings on March 6, 2020. When Naledi Chirwa, an MP for the Economic Freedom Fighters, accused some SANDF members on March 30 of perpetrating rape and sexual abuse during the same deployment, @uLerato_pillay attacked her in a series of tweets leveraging her status as a foreign national. Similar tweets about these soldiers were made on May 6 and again on June 16, calling on the Minister of Defense to drop the legal defense. An emphatic plea on June 15 sought help for “Xola,” one of the soldiers that had apparently reached out to @uLerato_pillay.

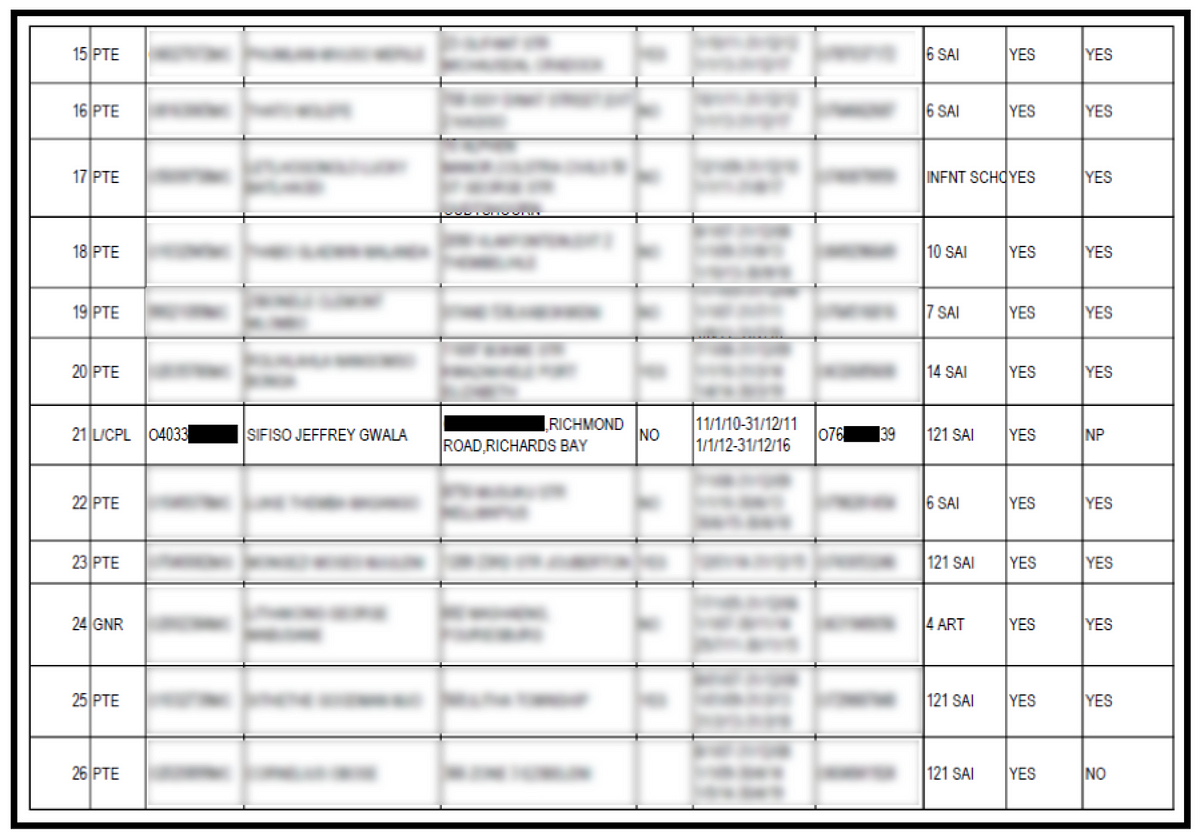

This legal challenge, lodged in the Gauteng division of the High Court, sits at the center of these 34 soldiers’ status as paid SANDF members. It is also within these court documents that the reason behind @uLerato_pillay’s advocacy becomes clear.

Listed among the names of these 34 soldiers is a familiar name: Sifiso Jeffrey Gwala. Xola, on the other, hand, does not appear among these 34 names.

These documents provided Gwala’s address, telephone number and base of operations, which was 121 SA Infantry Battalion at Matubatuba near Richardsbay in KwaZulu-Natal. @uLerato_pillay has mentioned this specific infantry base twice before.

Gwala’s phone number has been used to create multiple Twitter accounts and matches the phone number linked to @uLerato_pillay’s Twitter account around early June 2020. The same phone number matched the recovery number for both email addresses that could be linked to @uLerato_pillay as well.

Both email addresses — one hosted at yahoo.co.za and another at gmail.com — could be matched to the name Sfiso Gwala. The Gmail address in question ends with *88, which is also Gwala’s year of birth.

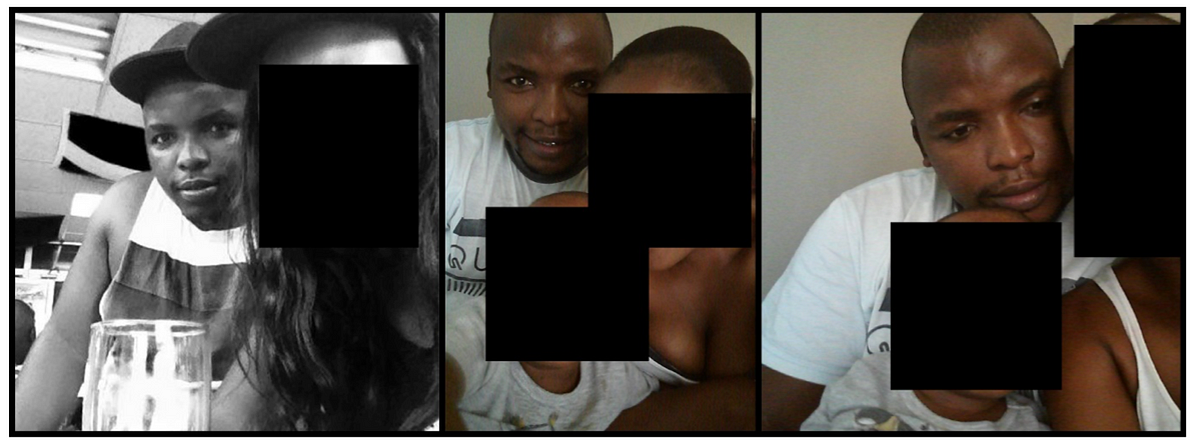

Although the Sfiso J Gwala Facebook profile identified earlier is no longer accessible, a woman that appears to be Gwala’s partner did not immediately do the same. Her profile still contained several photos of both herself and Gwala. Although she is not affiliated with the SANDF herself, her profile indicated she liked the Facebook page of SANDU, the union taking up the legal challenge of the 34 soldiers.

This provided three photographs identifying Gwala clearly.

The DFRLab reached out to Gwala for comment using his phone number and both his email addresses but has received no response.

Conclusion

In a country with a history of fatal violence directed at foreign nationals, incitement along xenophobic lines carries a very real risk. Besides the blatant disregard this has for human rights and the South African constitution, these protests quickly shift away citizenship to xenophobia and tribalism once it hits the ground.

Amid this, an influential yet anonymous account has the ear of opportunistic politicians that, while allegedly unaware of its identity, are keen to tap into the popular support its xenophobia generates.

In identifying the individual behind the account, there is a possibility that, when the powder keg next ignites, institutions such as the Human Rights Commission and law enforcement will know where to start looking for the one holding the match.

Jean Le Roux is a Research Associate, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in Cape Town.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.