Two separate companies managed networks with different goals— one political, the other commercial

On January 12, 2021, Facebook announced that it had removed two local networks in Brazil run by marketing companies that were engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior. One of the networks was focused on the state of Espírito Santo, in Southeastern Brazil, and the other in Paraná, in the south.

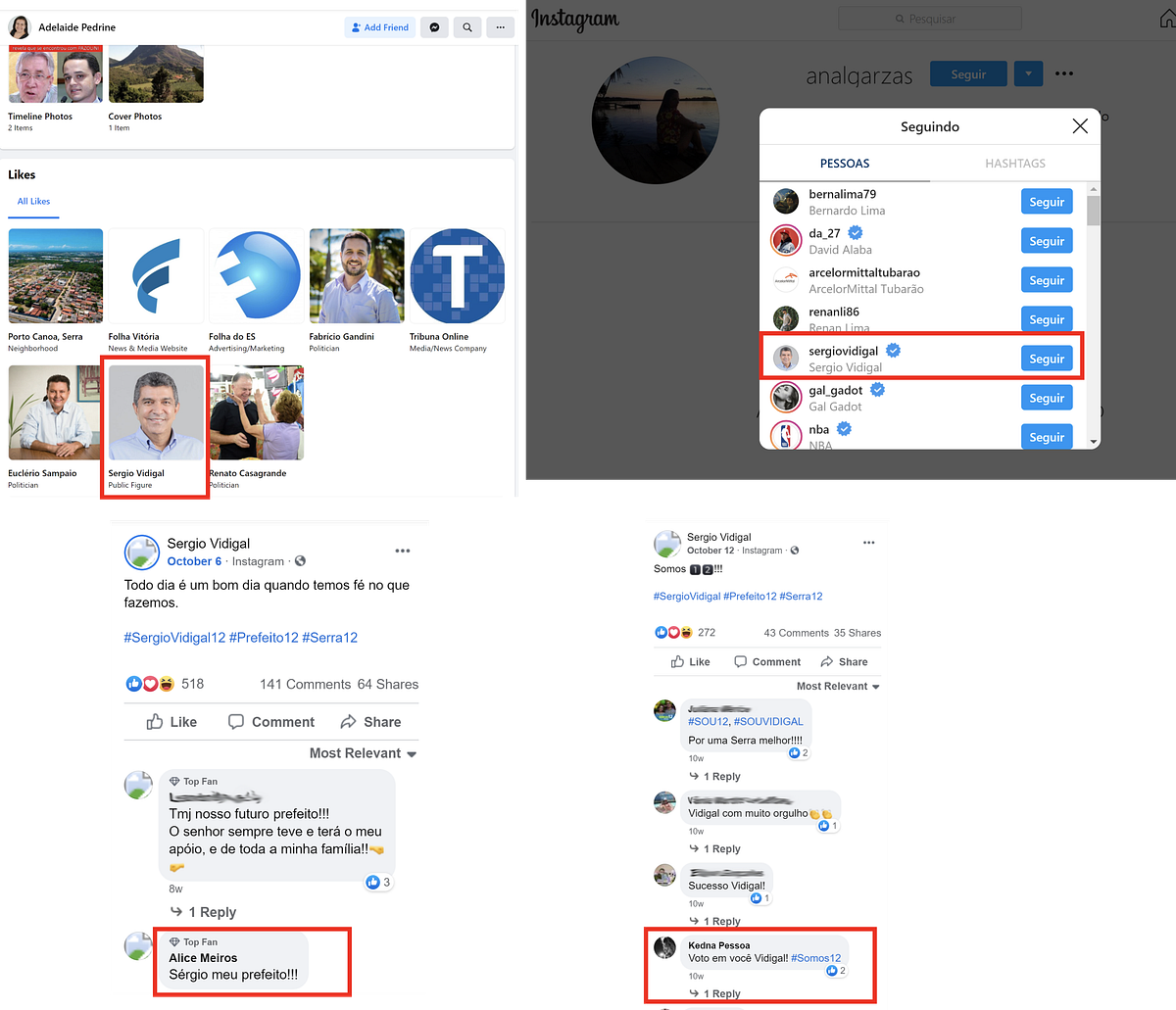

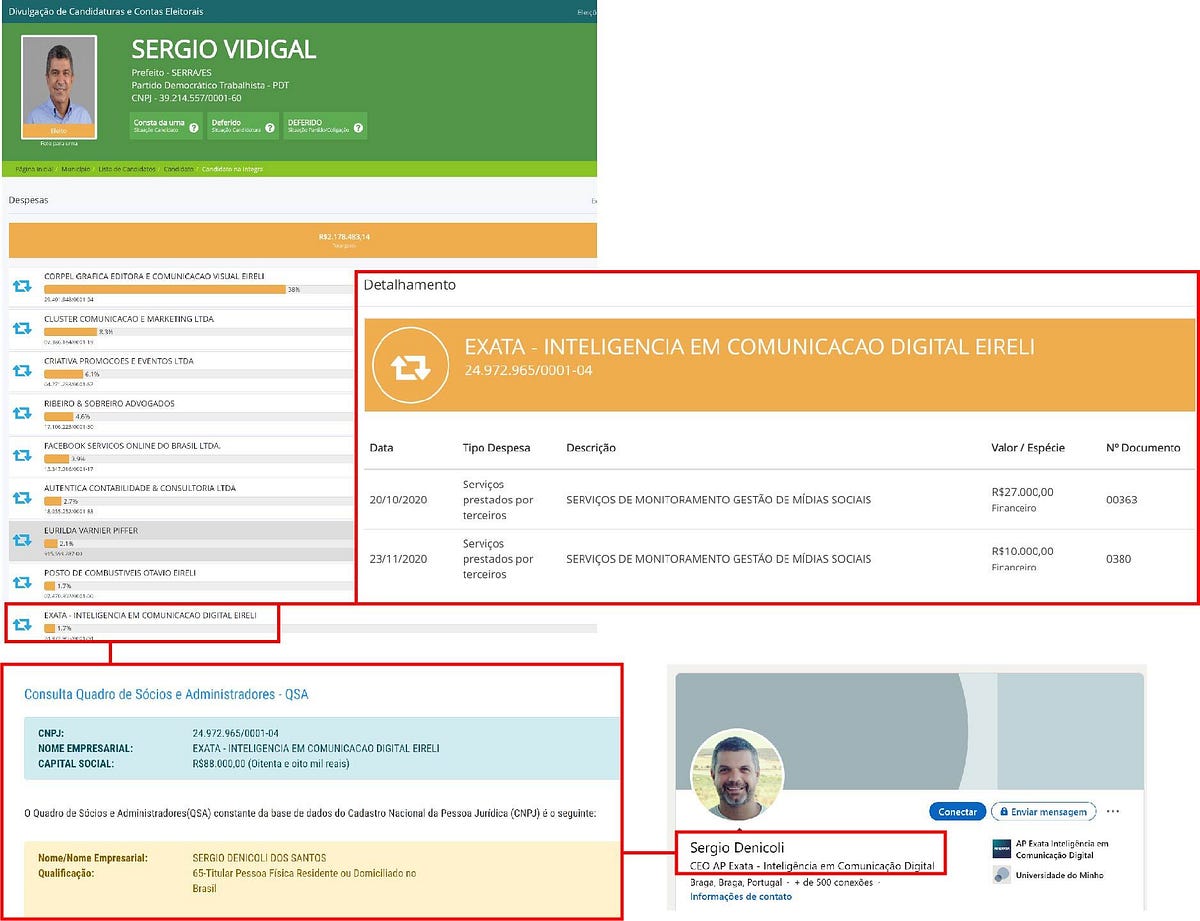

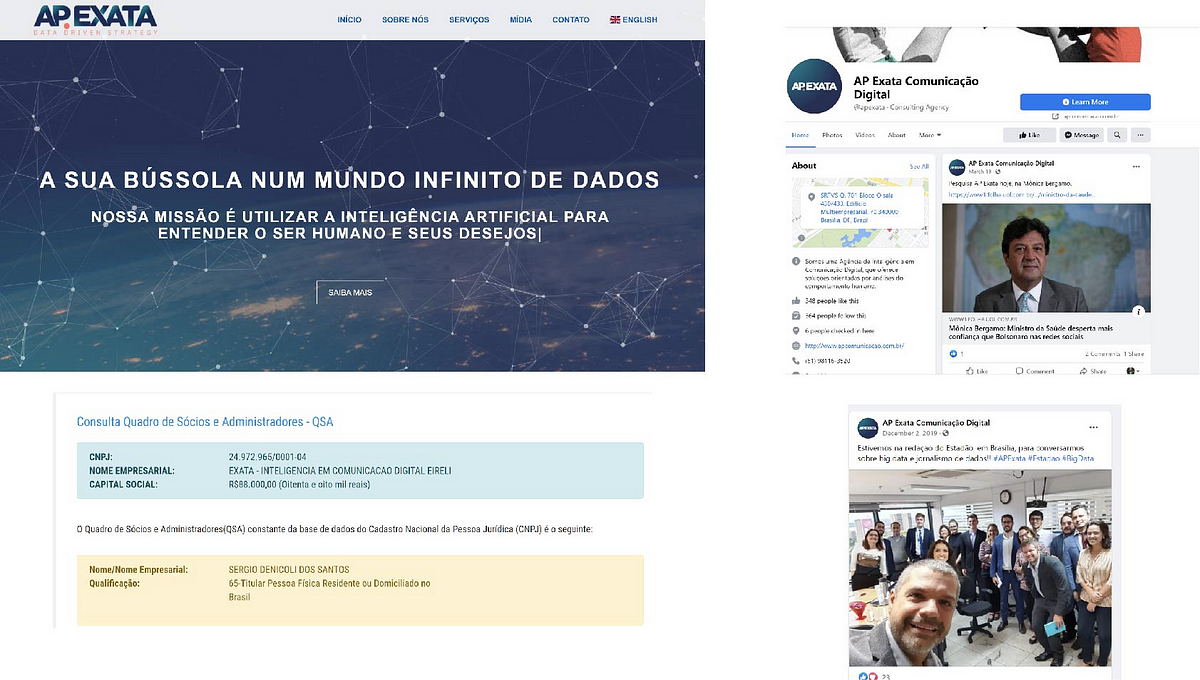

Facebook attributed one of the networks to a digital strategy company named AP Exata. A “twin company” (with the same CEO and almost the exact same name) was hired by the campaign of Sergio Vidigal, the elected mayor of Serra, a city of 410,000 people in Espírito Santo. His campaign’s spending receipts, submitted to the Electoral Justice at the end of his campaign, showed that he hired a company called “Exata — Inteligência em Comunição Digital Eirelli” for 37,000 reais ($6,900 USD) to “monitor social media management.” Exata’s owner is Sergio Denicoli, who is also the CEO of “AP Exata Inteligência em Comunicação Digital Ltda.” Vidigal, a member of PDT (Democratic Labor Party), was elected in November 2020 and sworn into office on January 1, 2021. The second network was connected to operators that were trying to boost sales of products online.

Ideological and political disinformation receive a lot of attention in Brazil, especially because of President Jair Bolsonaro’s insistence in making false claims and the group known as the “Hatred Cabinet” — government employees who spread positive propaganda about the president and negative slander about his opponents. The two networks that Facebook recently removed illustrate how disinformation-as-a-service, i.e., companies engaging in disinformation for profit, is a worrisome trend in the country, as it is elsewhere around the world.

Inauthentic digital strategy

According to Facebook, the network that worked in the state of Espírito Santo was connected to AP Exata, a private marketing firm that offers digital strategy and data-driven analysis in Brazil and Portugal. Using only open source evidence, however, the DFRLab could not confirm that the assets removed by Facebook were linked to AP Exata.

In a statement, Facebook noted:

This network used fake accounts — some of which had already been detected and disabled by our automated systems — to pose as locals in the state of Espírito Santo, like and comment on content related to candidates in the local 2020 elections to make it look more popular than it was. This activity focused on three municipalities in the state of Espiríto Santo — Serra, Vitória and Cariacica — and amplified the Pages and posts related to mayoral candidates in each town. In particular, the people behind this campaign re-shared and commented in Portuguese on posts about a candidate from the Democratic Labour Party in Serra, a candidate from Cidadania party in Vitória and another candidate from DEM party in Cariacica.

We found this activity as part of our internal investigation into suspected coordinated inauthentic behavior in the region. Although the people behind this network attempted to conceal their identities, our investigation found links to AP Exata Intelligence in Digital Communications, a public relations firm with offices in Brasília, Vitória and Braga in Portugal.

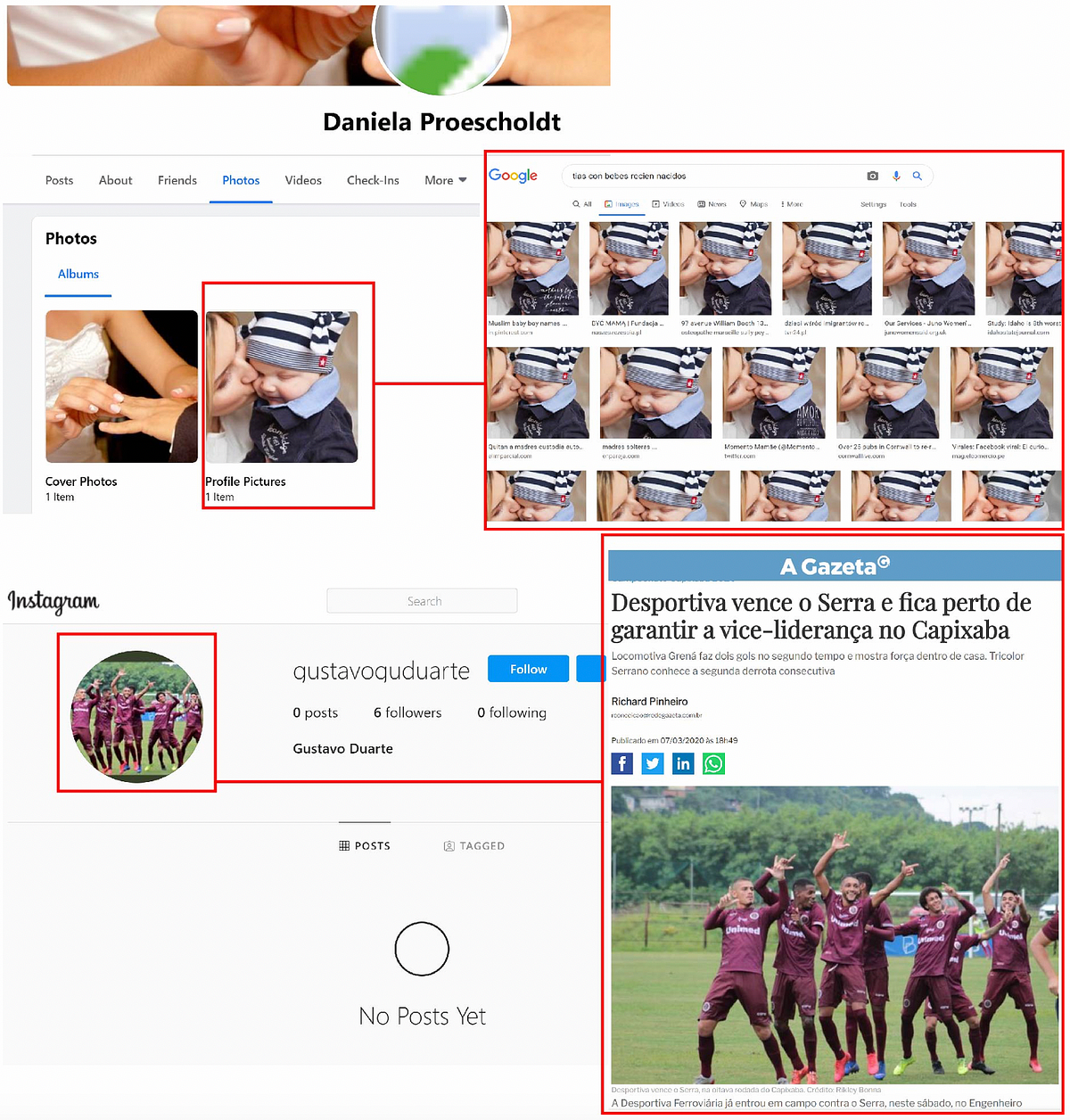

In total, Facebook removed 34 user profiles and 18 Instagram accounts connected to the network. The Facebook profiles and Instagram accounts included fake and duplicated accounts with stolen pictures and little activity.

Most of the Instagram accounts were friends with each other, a strong indicator that they were part of the same network.

In common, all these accounts had connections to Sergio Vidigal, who was elected mayor of the city of Serra in November 2020. The accounts were used to falsely boost Vidigal’s social media presence during the 2020 local election. Accounts liked his Facebook page and engaged with his posts; some of them were “top fans” of his page, meaning they engaged with his content frequently. They also followed him on Instagram.

Vidigal was elected mayor in a runoff on November 27, 2020, with 54 percent of the vote. His campaign spending receipts submitted to the Electoral Justice at the end of his campaign show that he hired AP Exata for 37,000 reais ($6,900 USD) to “monitor social media management.” There is no open source evidence, however, that Vidigal knew that fake profiles were being used in his campaign. Brazilian electoral law does not specify that the use of fake accounts to boost electoral contents is a crime. However, according to experts, such activities could possibly be considered a violation of electoral rules.

AP Exata is a communications agency whose analysis of social media has been published by legacy media outlets in Brazil. The Facebook profile of its funder, Sergio Denicolli, was removed from the platform as part of the takedown as well.

“Making money online”

Facebook also removed a network of 25 accounts, three pages and 10 Instagram profiles connected to a marketing firm in Paraná, a state in the south of the country. The operation used fake and duplicate accounts to boost the sale of online products via websites that give commissions to sellers.

According to Facebook:

We found two clusters of activity that used fake accounts — some of which had already been detected and disabled by our automated systems — to post, comment and manage Pages. One of these Pages posed as an independent news entity. This activity targeted two municipalities in the state of Paraná — Almirante Tamandaré and Colombo — and focused on the 2020 regional elections. The majority of likes and comments on this network’s Pages were by their own accounts. The people behind this campaign posted in Portuguese about the mayoral elections. They also shared supportive commentary about the current mayor of Almirante Tamandaré and the mayoral candidate associated with the PSD party in Colombo, as well as criticism of these candidates’ political opponents.

We found this activity as part of our internal investigation into suspected coordinated inauthentic behavior in the region. Although the people behind it attempted to conceal their identities and coordination, our investigation found links to Continental, a PR Agency based in Curitiba, and other individuals in the state of Paraná.

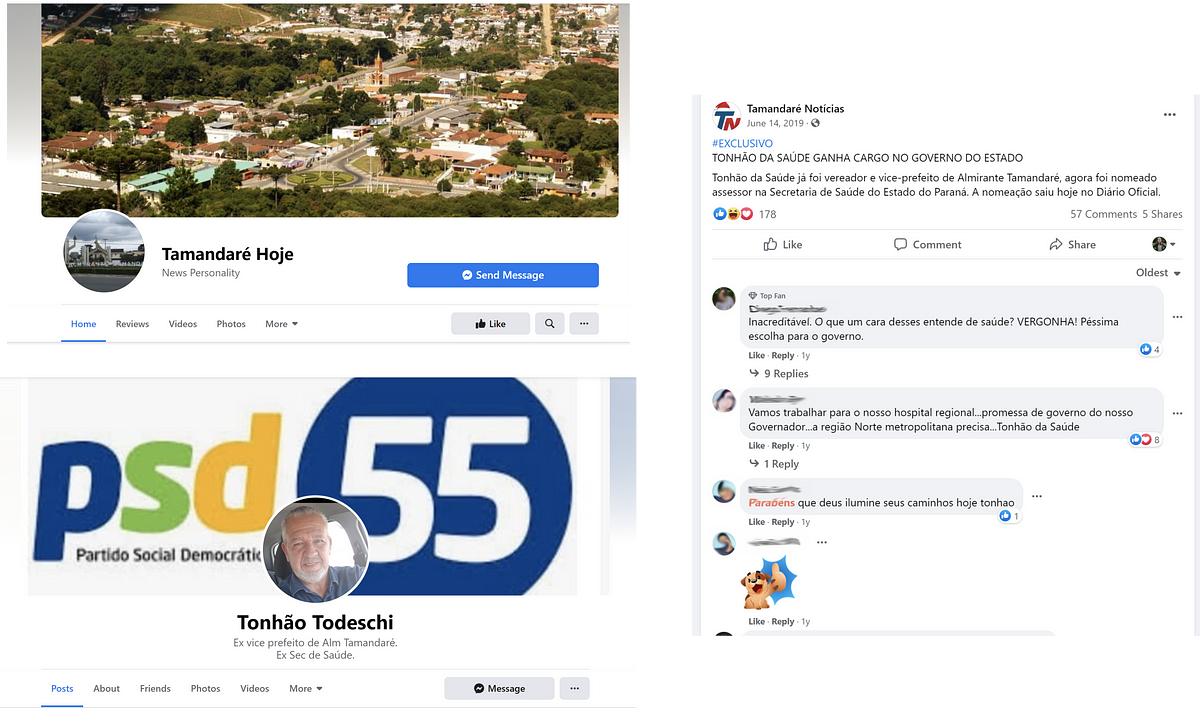

One of the accounts removed belonged to a politician called Antonio Claret Giordano Todeschi. Known as Tonhão Todeschi, he is affiliated with the PSD party and is the former vice-mayor of the city of Almirante Tamandaré. Another page, Tamandaré Hoje, pretended to be a news outlet. The latter published positive posts about city hall decision-making and about Todeschi himself. Looking at open source evidence, however, the DFRLab could not find connections between these two accounts and the rest of the network.

The impact of the operation was low, suggesting it was not successful in meeting its goals. In all, Facebook removed seven Instagram accounts, five Facebook accounts, and three Facebook pages that amounted to some 5,000 followers and friends.

The operation was connected to a small marketing firm named Continental Marketing. On Facebook and Instagram, the company posted tips for clients to improve their online strategies and offered services such as social media management. Services provided included posting on client’s social media accounts and automating replies on Instagram. The company also used Facebook to sell online courses and other services, such as creation of websites and social media management with “emphasis on artificial intelligence.”

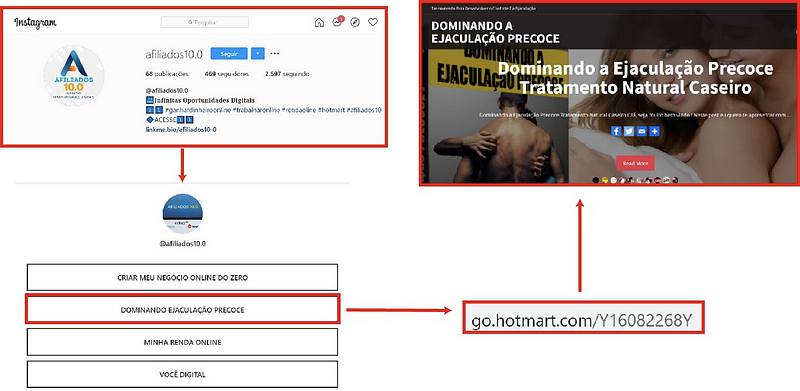

Facebook also took down a page named Afiliados 10.0 (“Affiliated 10.0” in Portuguese), which described itself as a community and marketing services provider. The page targeted people that worked as marketing affiliates, earning commissions for promoting products made by other people or companies using e-commerce platforms such as Hotmart and Monetizze.

On Instagram, the page promoted a website for men trying to prevent premature ejaculation. The website sold a “homemade” method to prevent the issue that was commercialized in the Hotmart platform, indicating that it was used as part of the “affiliated marketing” strategy.

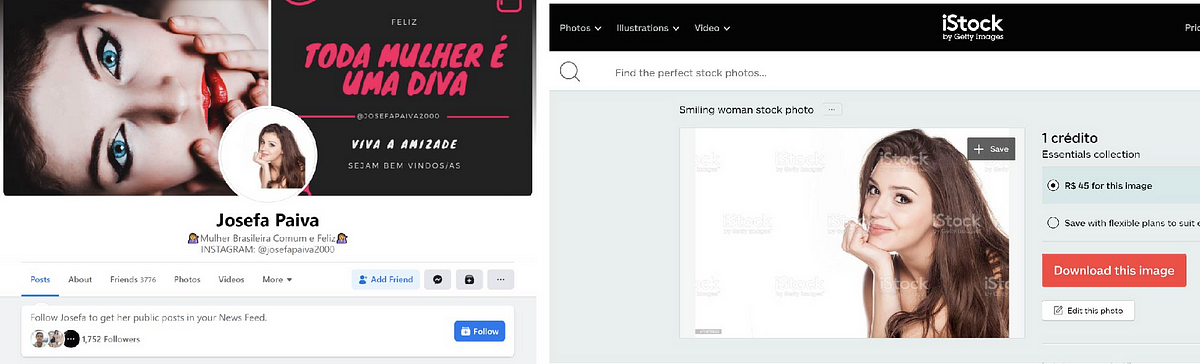

The most prominent account in the set belonged to a fake persona named Josefa Paiva. The account used an iStock image as its profile picture and had around 1,750 followers on Facebook at the time of removal, many of which were international profiles that did not engage with the content.

On the Facebook account, the account promoted both Afiliados 10.0 and Continental Marketing services.

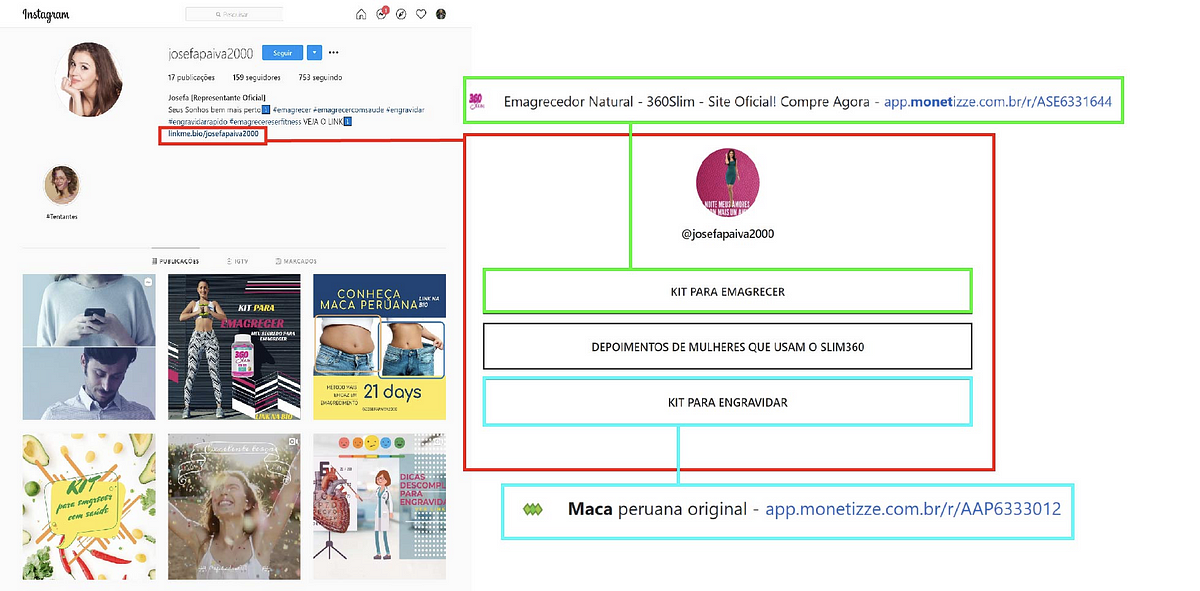

“Josefa” pretended to be an influencer selling weight loss and pregnancy-related products. On Facebook and Instagram, the persona posted links to products marketed via Monetizze, indicating an intent to boost sales from affiliated sellers. A Facebook profile, a group, a page, and an Instagram account associated with this persona were taken down by Facebook.

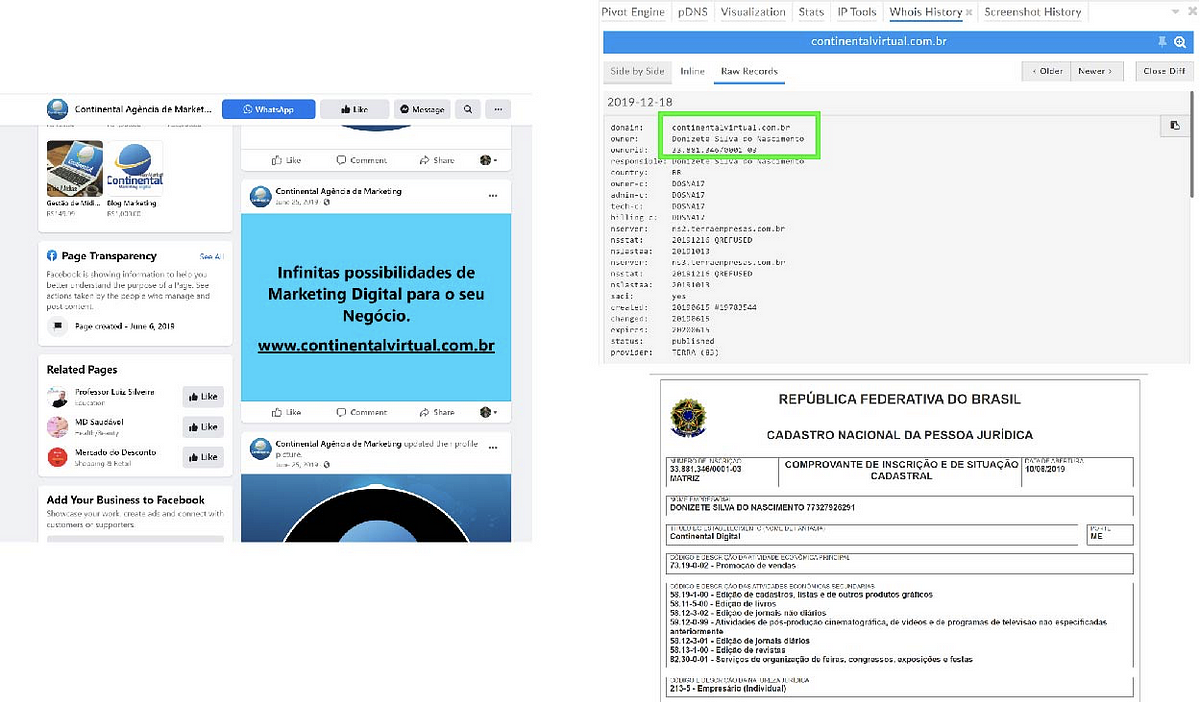

Both Continental Marketing and Afiliados belong to a person named Donizete Silva do Nascimento, who also had two duplicate Facebook accounts removed. He registered the website www.continentalvirtual.com.br, and the firm Continental Virtual, as seen in the image below.

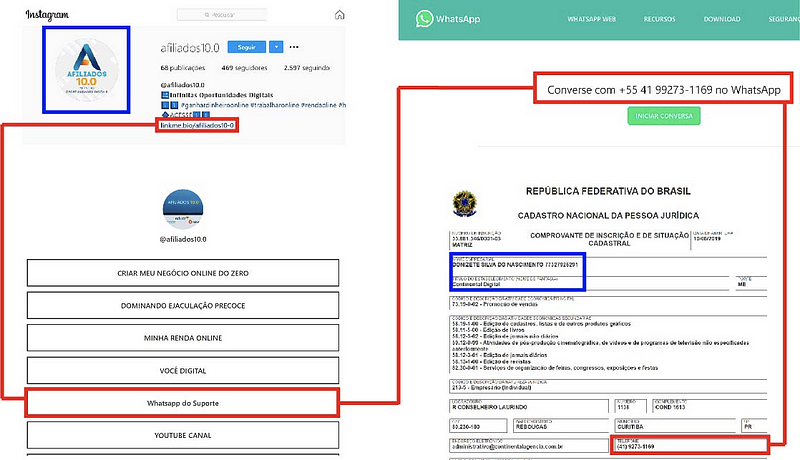

Afiliados 10.0 was also connected with Donizete and his Continental Digital. Its Instagram page had a link to the WhatsApp support of Afiliados 10.0, which used the same mobile phone number that Donizete used to register Continental Digital with Brazil’s tax office.

Despite the low engagement, this operation displayed some sophistication as it was a cross-platform effort. Both the Josefa persona and the Afiliados page had WhatsApp groups; Afiliados also had a Facebook page; and Continental has a LinkedIn profile. Cross-platform operations are worrisome — especially when they have non-commercial motivations, which does not appear to have been the case with this operation — because they have the potential to reach different communities that might engage with inauthentic assets unwillingly.

Conclusion

Information operations often follow two different operational models. The first involves the use of an intermediary public relations or digital marketing firm that provides “disinformation-as-a-service” for profit; the second directly involves in-house political staff in the operation and coordination of the information campaign.

In July 2020, Facebook discovered an information operation in Brazil that followed the second model. The DFRLab was able to confirm that this network had the participation of employees of President Bolsonaro, his sons, and other politicians from the PSL party. Despite appearing to be rarer in the international sphere — likely because it is easier to associate with the political figures involved — this model is often discussed in Brazil because of what is known as the “Hatred Cabinet,” an effort by Bolsonaro-affiliated government employees that promote the Brazilian president and attack his opponents.

Both networks that Facebook announced in January 2021 followed the most common operational model of disinformation, in which public relations and digital strategy companies act to profit off of disinformation and inauthentic behavior. It should serve as a reminder that information operations take different shapes and forms, all of which require specific policy tools to be handled.

UPDATE: This article was revised to include the presence of a second, similarly named company to AP Exata, both of which are related.

Luiza Bandeira is a Research Associate, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Daniel Suárez Pérez is a Research Assistant, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Jean le Roux is a Research Associate, Sub-Saharan Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Tessa Knight is a Research Assistant, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Zarine Kharazian is Assistant Editor with @DFRLab and is based in Washington, DC.