Kenton Thibaut, “China-linked WeChat accounts spread disinformation in advance of 2021 Canadian election,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 4, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/china-linked-wechat-accounts-spread-disinformation-in-advance-of-2021-canadian-election-cb5a8389049.

China-linked WeChat accounts spread disinformation in advance of 2021 Canadian election

WeChat accounts amplified narratives critical of Conservative Party prior to the September 2021 parliamentary election

BANNER: A mobile phone user shows an icon of the messaging app WeChat on the App Store on his smartphone in Ji’nan city, east China’s Shandong province, July 19, 2017. (Source: Oriental Image via Reuters Connect)

China-linked actors took an active role in seeking to influence the September 20, 2021 parliamentary election in Canada, displaying signs of a coordinated campaign to influence behavior among the Chinese diaspora voting in the election.

As many democracies have watched with concern the uptick in exposed Chinese influence operations, expert assessments of this trend have been unable to find compelling evidence of real-world impacts of Beijing’s online behavior. Recent assessments suggest that Chinese influence operation efforts are becoming more sophisticated from the growing number of case studies on the topic. For example, China has recently stepped up its operations to game search engines to spread conspiracy theories on COVID-19 origins, to expand its network of inauthentic accounts across a variety of platforms, and to influence an increasing number of real social media users.

However, unlike in the case of Russia, which has historically been a more assertive and successful operator in this space, current assessments have suggested that the impact of China’s efforts in mobilizing offline activities remains very limited. This may be about to change. China seems to have found increasing value in openly attempting to influence communities through its popular WeChat messaging app as a means of galvanizing public favor internationally toward its own government and activities, including — as this case will show — attempting to impact electoral outcomes in democratic countries.

Evidence from the most recent Canadian election underscores the value China sees in controlling the information flow to its diaspora community. It also suggests an uptick in Chinese efforts to translate its online efforts into offline action.

Understanding WeChat

China’s propaganda efforts have long prioritized Chinese diaspora communities abroad, seeing these groups as key to building a positive amplification network around the globe. While current assessments have found that the impact of its attempts to spread positive messages on English-language platforms like Twitter have so far had limited reach, this may not be the case for Chinese-language apps like WeChat.

WeChat is China’s most popular messaging app, with a monthly user base of over 1 billion users. The platform does not restrict users to maintaining only one account, but each account is tied to a unique phone number and subject to extensive restrictions around abuse of maintaining multiple accounts. WeChat was first released by Chinese technology firm Tencent in 2011. In addition to its messaging features, WeChat has become a multipurpose platform that integrates a variety of services, from mobile payments to ride hailing and social engagement.

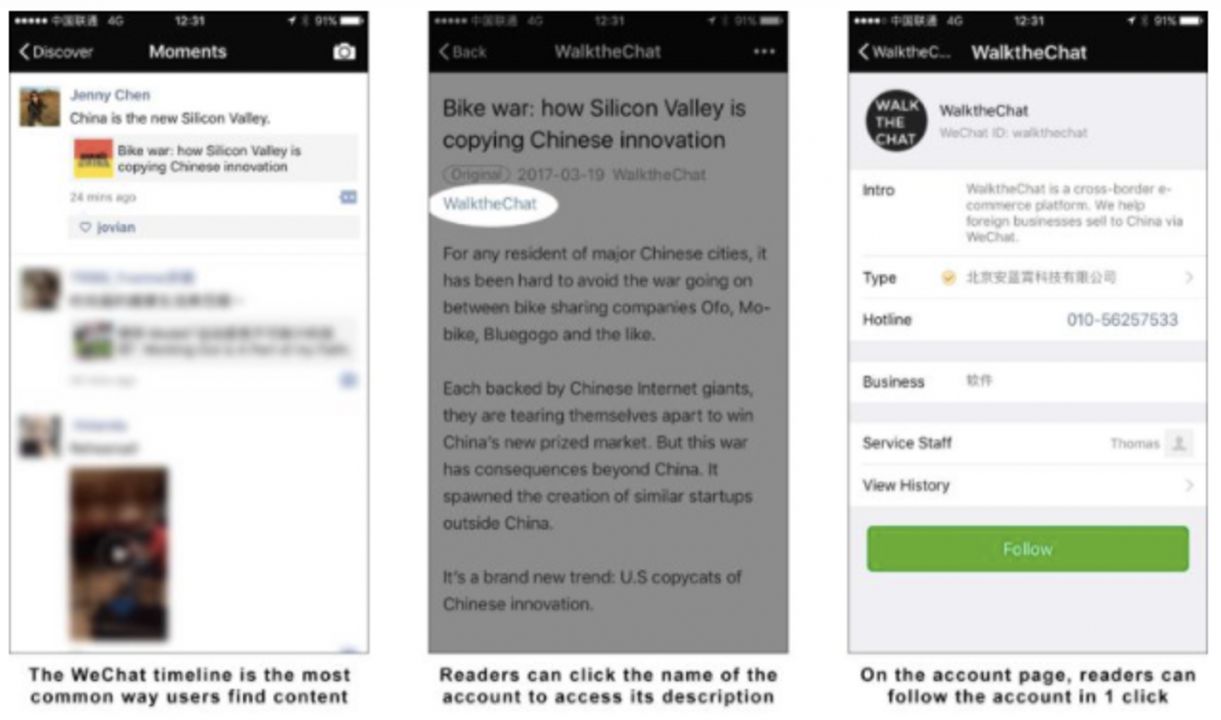

The platform can be thought of as combining the features of WhatsApp’s messaging service with Facebook’s social media functionality. WeChat account holders can engage in private or group chats with other user accounts, and they can also post life updates, photos, and articles through its “Moments” feature, where other user accounts can comment or “like” these posts.

Many companies, enterprises, and government organizations operate official WeChat accounts. These accounts are similar to Facebook pages — they allow businesses or organizations to gain followers, send them direct push notifications, and provide clickthrough links to external websites. For example, the Shanghai Municipal Education Department operates its own public WeChat account (上海教育) that updates followers on new policies and regulations, and publicizes department-related events and achievements.

In 2017, WeChat rolled out its “mini programs,” which essentially function as sub-applications within the platform, complete with e-commerce and other types of built-in functionality. These mini programs are almost exclusively operated by large companies or organizations, as the administrative burden of creating and maintaining them is high. For those that do, however, they can operate commercial services within the app — as opposed to directing a user offsite, as would happen with an official account — and gain access to broader WeChat usage data for those users interacting with the mini program.

In short, WeChat functions as almost a “one-stop-shop” for its users. For example, a WeChat user can receive updates on their friends’ lives from the “Moments” page, chat with their family about dinner plans, pay their phone bill, catch a ride downtown, and buy the newest pair of designer shoes, all without exiting the WeChat app.

Given its popularity especially among the Chinese-speaking world, WeChat is the third most popular social media platform in the world and overwhelmingly the primary platform of communication between Chinese diaspora abroad and those living in China. It is also the primary outlet from which many diaspora Chinese — especially first-generation immigrants — receive their news. A May 2020 report from Graphika found that overseas WeChat accounts are still subject to censorship and surveillance from state-linked actors in Beijing. Additionally, researcher Yaqiu Wang of Human Rights Watch found that Chinese censors must approve content from media outlets publishing for an overseas Chinese audience on WeChat before it can be published. This means many in the diaspora receive a majority of their online information — good or bad — through a Beijing-approved lens.

One challenge in measuring the impact of disinformation that can circulate in WeChat is the closed and siloed nature of the platform. WeChat account users have three main ways to see the information. First, if they follow an official account, they will receive push notifications in the WeChat “Chat” section when the news briefing is published, which they can click on to see the full news brief.

Second, another way to see this information is if it appears on a friend’s “Moments” timeline, which operates similar to a Facebook user account’s news feed, except it is more private. There is no option to have a public-facing timeline such that your updates are only seen by friends who you have verified, while comments on your timeline can only be seen by people who are mutual friends with the commenter. WeChat users also cannot see each other’s friends list.

Lastly, mis- or disinformation can be shared in private groups or group chats, which are impossible to access unless you are added as a member. This limited access closes the information loop; the only way to rebut bad information is to gain access to the discussion.

HuayiNet, “Toronto Consulate,” and the Chinese government

The principal actor behind the Canadian election case was HuayiNet, a private translation service with deep ties to a number of Chinese government entities. In particular, the translation firm has a close working relationship with Chinese consulates in both Canada and the United States, as well as with other Chinese government and government-affiliated organizations, including the Ministries of Culture and Foreign Affairs. HuayiNet also works closely with the China Association for the Promotion of International Friendship, which is the public face of China’s main external propaganda arm, the United Front Work Department. China’s use of its vast subnetwork of pseudo-government or government-adjacent entities in spreading approved narratives has been well-documented in other contexts, and the evidence in this particular case supports the notion that official WeChat accounts operated by HuayiNet at minimum take cues from Chinese state media.

One such official WeChat account bears the name torontolingshiguan (“Toronto consulate” in Chinese). The account, however, is run by an employee of HuayiNet and not directly by the Chinese government, as the name would imply. This fact appears to be intentionally obscured to give users the initial impression that it is a formal part of the Chinese government, as opposed to being connected to — but not a direct part of — it.

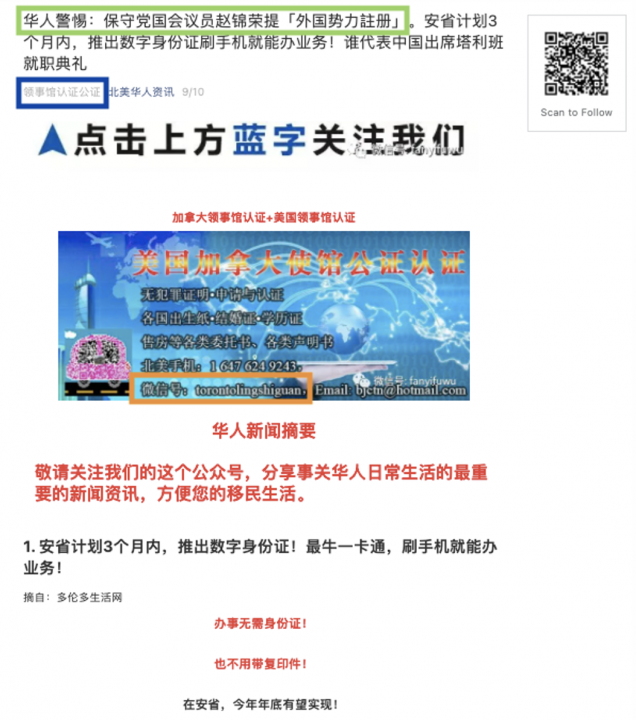

The torontolingshiguan official account provides a daily news briefing titled beimeihuarenzixun (“North American Chinese Info”), aimed at the Chinese Canadian diaspora community. The news briefing provides a list of the top ten or so news items the account operators deem as most relevant to Canadian Chinese diaspora affairs. These news items are gathered from different sources on WeChat, including official WeChat account pages for the Chinese embassy, opinion pieces published on the official account pages of other news sources, and posts from individual users to their respective accounts.

In addition to mixing in misleading content or disinformation with more neutral news topics, the intentional naming of the torontolingshiguan official account further imputes an air of officially sanctioned and verified reporting to the stories featured on the news briefing, as it blurs the line between being run by a notionally independent translation service and that of an official Chinese consular source. Just glancing at the official account name, a less discerning reader could easily accept that the news briefing was supplied by the Chinese consulate in Toronto.

An additional layer of confusion for the casual reader is that the official account features a designation that it is “consulate certified.” This designation is supposed to indicate that HuayiNet is certified as a business provider to the Toronto consulate, not that the content of the news briefing is certified by the consulate itself, but this may not be immediately clear to users.

Targeting the Chinese diaspora during the 2021 Canadian elections

The DFRLab uncovered a number of articles on WeChat aimed at the Chinese diaspora population with the aim of influencing the diaspora vote. While many of these posts provided resources for how to access official information on voter registration and the platforms and positions of candidates running in particular areas, an equal if not larger number of accounts posted disinformation intended to dissuade Chinese voters from supporting candidates holding anti-China views. Among these posts were many from torontolingshiguan.

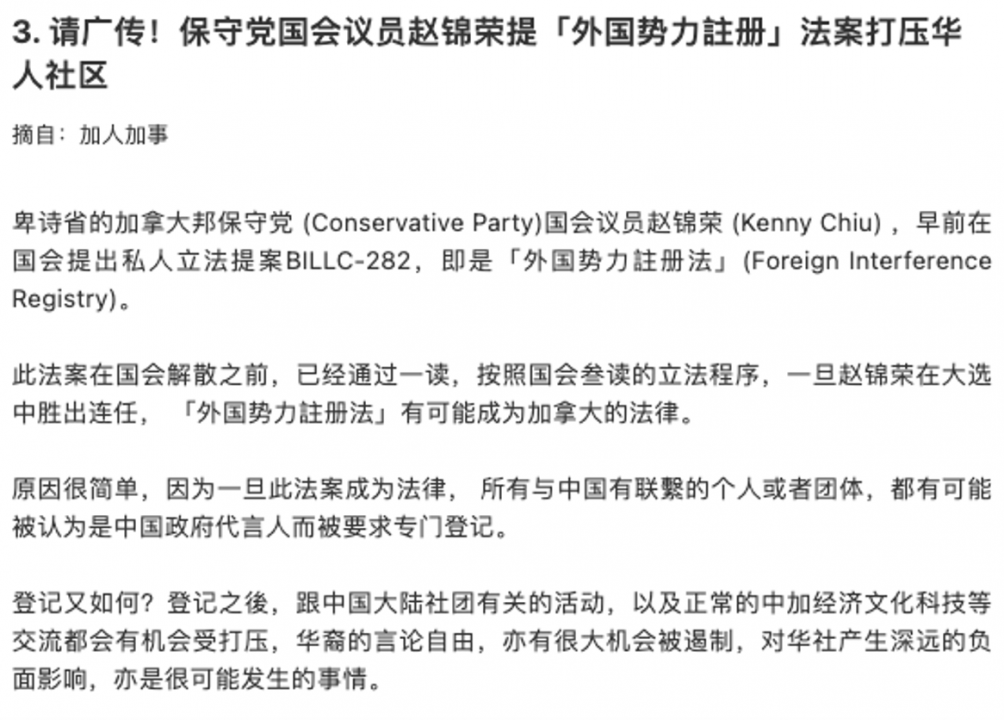

In its September 10 news briefing, torontolingshiguan included an essay lifted from a September 9 article posted to jiarenjiashi, an official WeChat account run by Today Commercial News (TCN), a media organization purporting to share business and lifestyle-related news relevant to Chinese speakers in Canada. The September 9 essay featured warnings to the diaspora community regarding Kenny Chiu (赵锦荣), a Conservative Party member of parliament (MP) then seeking reelection, while the headline for the September 10 news brief — which has since been taken down — read: “Chinese take heed! Conservative MP Kenny Chiu to Raise ‘Foreign Influence Registration Act.”

The essay “urges readers to spread the word” that Chiu, if elected, would pass a law that would result in widespread suppression and monitoring of the Chinese community in Canada — a claim Chiu strongly refuted. In the news briefing, the essay was included as the third news item, following a piece detailing the Canadian government’s rollout of a new digital identification card and other straightforward news items. The tactic of embedding this kind of incendiary, misleading content alongside other largely neutral, information-based topics is designed to impute an air of legitimacy to it, attempting to move it from the realm of opinion — or deliberate misinterpretation, as was seemingly the case here — to that of fact in the mind of readers.

There are several strong narrative throughlines between Chinese official state media and the WeChat posts referencing the Canadian elections that indicate at least the potential of coordinated behavior. As mentioned above, the essay targeting Kenny Chiu was originally posted on the official WeChat account for Today Commercial News, which also has a presence on Facebook, other Chinese social media platforms like Weibo, and its own website. Its Facebook page is printed in traditional Chinese, used in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and features a number of posts spreading official Chinese narratives on topics ranging from Xinjiang to Hong Kong, including by using the same terms and phrasing.

For example, an article on TCN’s website from June 2019 described Hong Kong protesters as “thugs” (暴徒) who were engaging in violent tactics against peaceful police officers. This language mirrored similar language used by the official Chinese Communist Party newspaper, the People’s Daily, which in an August 2019 Weibo post used the hashtag #HongKongPoliceStandFirm alongside a call for the “severe punishment of Hong Kong thugs” (暴徒) for their “violent tactics” during street protests. Similarly, a November 2019 article from the People’s Daily Online also used the same language, calling for the “harsh punishment of Hong Kong thugs (暴徒).”

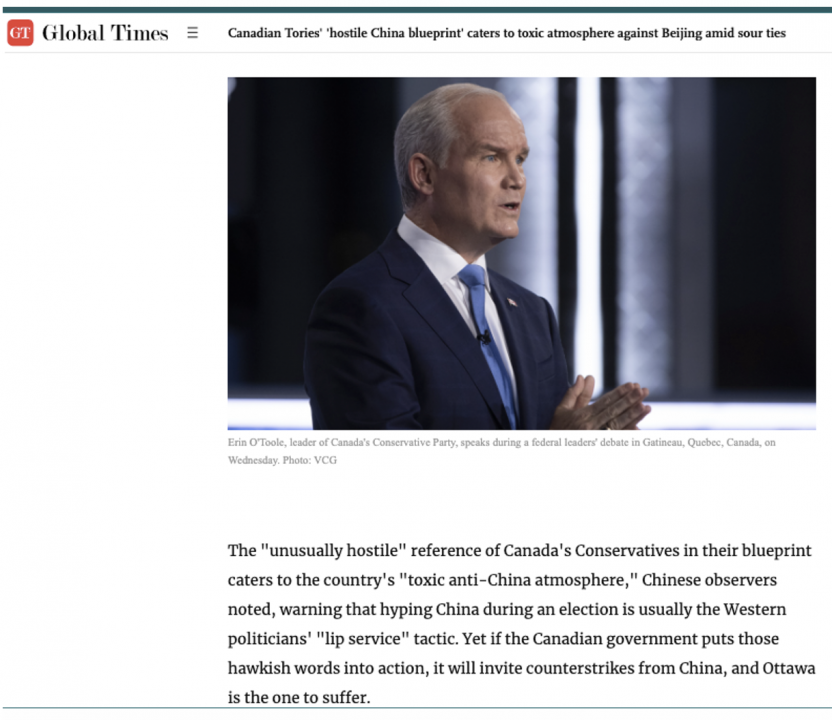

TCN published its story on the same day that Global Times — the nationalistic English-language offshoot of the People’s Daily — published a piece stating that the “unusually hostile” anti-China stance that Canada’s Conservative Party candidates were taking in the run-up to the September 2021 election would “invite counterstrikes from China, and Ottawa is the one the suffer.” It also claimed that Canada was acting as a shill for the United States, an accusation that has been made repeatedly in Chinese official media over the case involving Huawei executive Meng Wangzhou. The piece also reiterated past criticisms of anti-Asian racism in Canada and the United States, a tactic that Chinese media deploy with increasing frequency to counter widespread castigation from the international community regarding its treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

These narrative themes were repeated in other Chinese-language posts circulating on WeChat targeting Chiu and other Conservative candidates. For example, following Chiu’s election loss, a September 23 opinion article from the Global Times repeated claims that Chiu’s anti-China stance and his support for a bill that “many ethnic Chinese [say] will make any individual or group connected with China considered to be a spokesperson of the Chinese government, and be required to register with the government” had lost him the vote. The article was popular, receiving over 3,700 comments, with one of the “top voted” comments criticizing Chiu for “throwing away their ancestors without hesitation for [his] own benefit.” Similar narratives emphasizing how “anti-China politicians will be abandoned and defeated by Chinese voters” and that politicians would lose by “provoking China” were repeated and circulated on WeChat from various accounts catering to the diaspora community.

Following his re-election loss, Chiu blamed China’s attacks on him as one of the reasons he was defeated. According to an article in the National Post, former Canadian diplomat Charles Burton warned Chiu about the disinformation campaign on WeChat, “but there seemed little they could do about it.”

It is difficult to measure direct impact of such messages on election outcomes, especially given community concerns about the recent uptick in anti-Asian racism and the COVID-19 pandemic more broadly. Prior to the election, polling firm Mainstreet Research found that nearly two-thirds of self-identified Chinese voters surveyed stated that they would be supporting non-Conservative candidates, a change from previous voting behavior. In the case of former MP Kenny Chiu, he lost his re-election bid to Liberal Party candidate Parm Bains by nine points, a swing of more than 15 points from his prior election.

On top of this, following the election, the Chinese Canadian Conservative Association — a group representing Conservative-leaning Chinese voters in Canada — urged Conservative MP Erin O’Toole to resign, stating that the party’s anti-China stance alienated Chinese Canadian voters and ultimately cost Conservatives the election. They also urged the party to take a less “confrontational” stance toward China, as the use of racist tropes and othering language by some party members could foment hatred against the Chinese community. The unfortunate second-order effect of this is that authoritarian countries like China and Russia weaponize such societal cleavages to achieve their own interests.

The case of the Canadian 2021 election underscores that perhaps one of the areas with most “promise” for China in turning its online influence into offline mobilization is through influencing the debates taking place within Chinese diaspora communities in democratic countries. The Chinese government has a direct line of sight into and a degree of editorial control over the content these communities consume due to the nature and structure of WeChat’s platform, while evidence shows how Chinese state narratives travel from official sources to appear on WeChat programs specifically tailored to the diaspora community. Most troublingly, even if the confluence of China-backed narratives and changes in voting behavior is entirely coincidental, the message the Chinese Communist Party may be receiving is that its attempts to influence voter behavior led to favorable election results. As China’s attempts to influence debates around the world in its favor, ensuring access to multilingual sources of independent, fact-based news and information may help build up community resilience to foreign influence campaigns.