Fake Telegram group urges Africans in Ukraine to wear armbands used by combatants

Misleading and racist Telegram groups emerge as accusations of racism by border authorities go viral on Twitter.

Fake Telegram group urges Africans in Ukraine to wear armbands used by combatants

BANNER: People seen standing next to a generator while charging their phones at the Ukrainian-Polish border. Civilians fleeing the war in Ukraine for the safety of European border towns include citizens of African, Asian and Middle East countries. (Source: Reuters/Attila Husejnow /SOPA Images/Sipa USA)

As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine intensifies, foreign nationals in Ukraine have increasingly turned to neighboring countries Poland, Hungary, and Romania for refuge. Amid claims of racist treatment by border staff and a dearth of official communications from their own countries, many African nationals have now taken to closed messaging platforms to coordinate their own exit plans. While many of these channels have proved to be helpful, some have experienced racist trolls, and at least one of them turned out to be a fake channel set up to potentially harm Africans.

Posts to Telegram channels and WhatsApp groups share details of the border crossing process, the length of queues, and alternative routes out of the country. Some groups are also used to crowdfund transport, accommodation, and subsistence costs for members. Links to join these groups have been amplified on social media platforms, including Twitter and Instagram. However, several of these groups were joined by users that trolled these efforts by posting swastikas, explicit pornography, and violent videos depicting the killing of Black people.

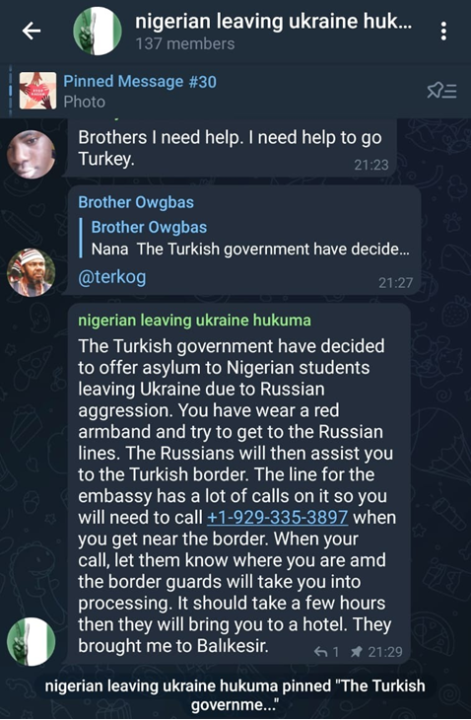

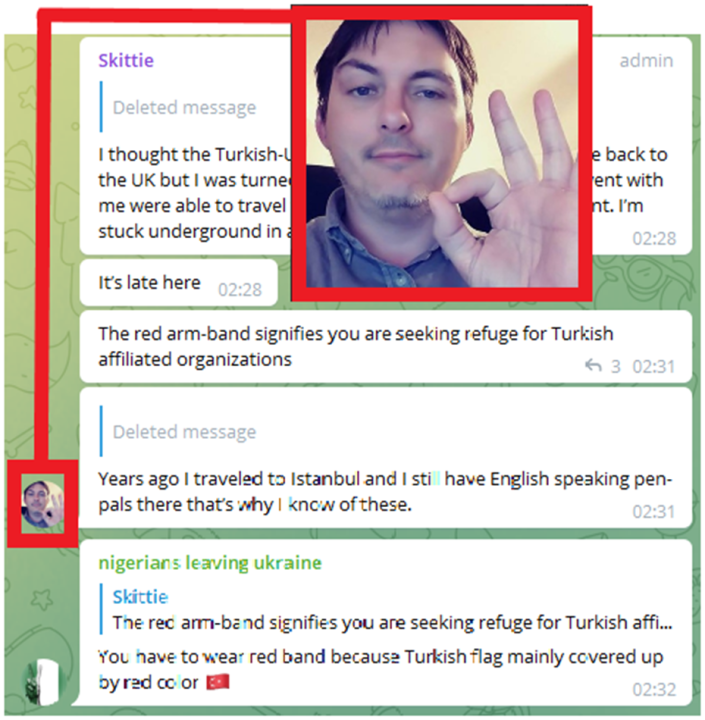

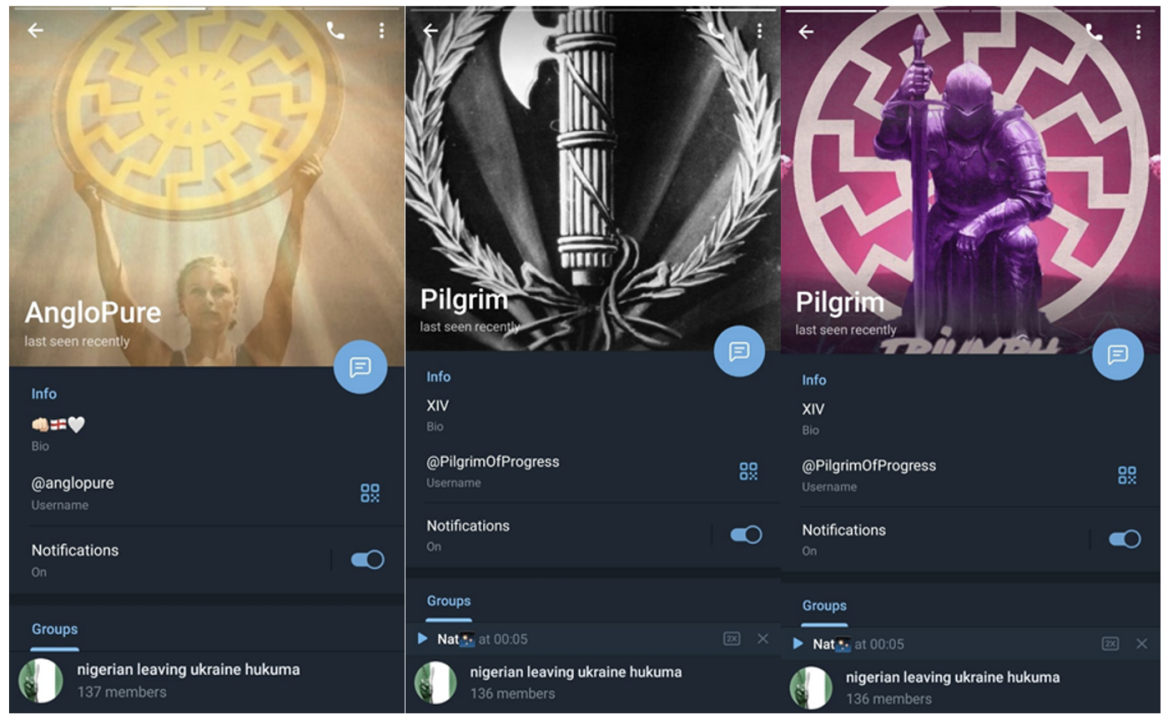

At least one group has been set up by suspected white supremacists and is actively encouraging Black Africans to put themselves in harm’s way. The channel, “nigerian leaving ukraine hukuma,” has advised members to wear red or yellow armbands in conflict zones to identify themselves as foreigners. But the advice is malicious; Russian soldiers and Ukraine’s civil defense forces use red and yellow armbands respectively to identify themselves. The advice could lead to Black civilians unknowingly identifying themselves as potential combatants in the middle of a conflict zone.

In the Telegram channel’s pinned post, the administrator urged users to don red armbands and approach the Russian-held port of Odessa as a way of escaping to Turkey. Additionally, the profile picture of at least one group administrator displays the white supremacist “OK” hand gesture, and several other users have white supremacist imagery in their profiles, including the sonnenrad and fasces.

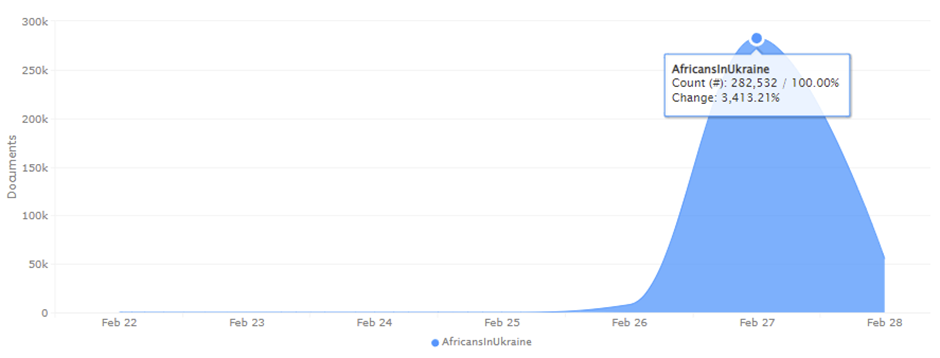

As these channels proliferate, Twitter users have raised awareness about racism by border authorities using the hashtag #AfricansInUkraine. The hashtag has been mentioned approximately 350,000 times since it first surfaced on February 24, including more than 282,000 mentions on Sunday, February 27. The hashtag trended on Twitter that weekend as interest surged on the platform.

While it was initially used to express solidarity with African nationals in Ukraine, #AfricansInUkraine quickly become a rallying point to highlight allegations of racial segregation and profiling by Ukrainian border authorities. A Twitter thread by @Damilare_arah compiled several videos showing the treatment of foreign nationals and the prioritization of Ukrainians, both en route and at the border crossings.

Alongside legitimate concerns of racism at the Ukrainian border, some of the most vocal proponents of the hashtag are accounts that are openly pro-Russian, label Ukrainians as Nazis, and call for the disbandment of NATO. There are indications of attempts to manipulate the popularity of the hashtag, although the volume of tweets by these accounts was rendered insignificant by the immense volume of organic #AfricansInUkraine tweets.

The incidents of racism at the border has raised the ire of the international community, with statements of condemnation from the African Union and African member states on the UN Security Council.