WeChat channels keep Chinese students in US tied to the motherland

How Chinese government perspectives are reinforced among Chinese students at US universities via WeChat.

WeChat channels keep Chinese students in US tied to the motherland

BANNER: (Source: Avishek Das / SOPA Images/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect)

Chinese university students studying in the United States continue to live within a Chinese information ecosystem, as Weibo, TikTok, Bilibili, and WeChat keep them tethered at home even when abroad. In particular, WeChat channels run by Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (CSSAs) are part of Chinese students’ everyday lives, helping them stay connected and take advantage of opportunities available to them in their universities. CSSA channels also play a more political role in the Chinese students’ lives by always presenting the official Chinese Communist Party (CCP) perspective regarding any topic, from immigration policies to businesses.

The CCP communication strategy toward students abroad, and the rest of the Chinese diaspora, shows two sides: positive messaging to boost a favorable perception of China and negative representation of Western societies. CSSA WeChat admins are often vocal advocates of pro-China interests and narratives. Accordingly, their daily WeChat posts orient regular students on what patriotic stances look like on matters touching China’s interests even tangentially. The intention may not be to convince the students per se, but to reinforce the messages they should convey to their Western peers.

Thus, US-educated Chinese students continue to be exposed to CCP narratives, regardless of whether they plan to stay in a Western country or return to China. By analyzing narratives in politically sensitive posts, this case study will shed light on the continuous reinforcement of the CCP’s worldview among Chinese students. This analysis — one of two in a series on CSSAs and WeChat — will contribute to understanding how WeChat is instrumental in keeping the Chinese diaspora committed — or at least acquiescent to — the goals of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (中华民族伟大复兴).

Constant supply of Chinese views for more than 300,000 students in the US

Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (CSSAs) operate on university campuses outside China, ostensibly providing Chinese students abroad with assistance in their studies, job hunting, and other tasks. CSSAs also typically organize campus events to celebrate Chinese holidays, for example, hosting a Lunar New Year dinner.

In 2018, Foreign Policy reported, “Chinese consular officials often communicate with CSSA leaders through group chats in the Chinese messaging app WeChat.” Consular officials have created WeChat groups for the presidents of all CSSAs in a particular region, they noted, to more efficiently “communicate announcements and requests directly to dozens of CSSA presidents.”

Within the Chinese government, oversight of CSSA activities falls under the scope of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council, within the United Front Work Department (UFWD). The UFWD is the party body responsible for spreading Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda abroad and expanding party influence. As such, CSSA activities support China’s broader goals on spreading Chinese influence abroad.

The platform WeChat is pivotal in reinforcing pro-China perspectives among the growing population of Chinese American students and academics, as well as non-university affiliated diaspora in the United States. Chinese-owned WeChat is the fifth most popular messenger app in the US, based on the number of users, according to Statista.

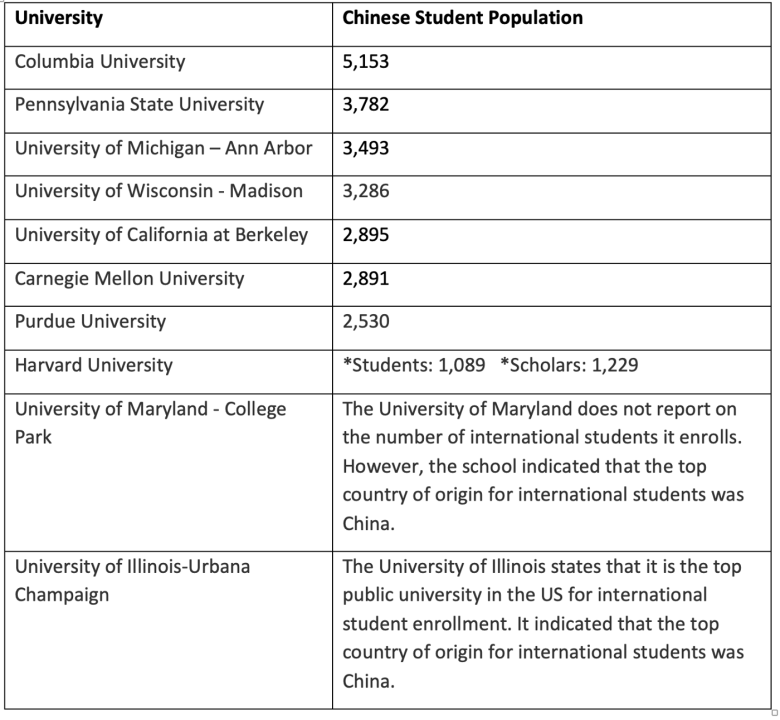

In the 2020–2021 academic year, 317,299 Chinese international students studied in the US, according to the US State Department program Open Doors. For this report, the DFRLab chose ten US universities with high enrollment rates from Chinese international students; we then reviewed content posted in the corresponding CSSA WeChat groups from October 2018 to February 2022.

CSSA WeChat channels are public or verified accounts to which users subscribe (In WeChat’s own terminology they are called “official accounts” [微信公众号]). Non-subscribers can read posts but are not allowed to react or share. Subscribers can share content from public accounts to their WeChat Moments [微信朋友圈], similar to a personal Facebook newsfeed. Users can also copy posts to share in private chats. WeChat official accounts are akin to Telegram public channels. Their posts are typically several paragraphs long and include pictures and sometimes memes.Frequently, CSSAs forward content from other official WeChat accounts. Posts may also include links to external sources. Most posts are written in Chinese but occasionally there are English translations, for example, when addressing university authorities.

The final dataset for this study comprises 14,692 posts that were categorized using a logistic regression classifier to help identify a sample of 119 potentially politically sensitive posts. In the sample, narratives aligned with China’s political values are present in posts classified as referring to politics, but also in seemingly non-political topics, like career opportunities at Chinese companies.

‘One China, a great power, a growing power’

The foremost political issue on which all CSSA groups agree is the “One China” principle (一个中国原则), aligning with the United Front Work Department’s priorities. The policy is a cornerstone position held by China, which claims sovereignty over Taiwan.

CSSA administrators have previously responded to on-campus events that may be viewed as challenging China’s “One China” principle. For instance, in August 2020, tensions arose among students at the University of Michigan after a seminar offered by the Center for Chinese Studies referred to Taiwan’s autonomy. The UMCSSA posted a statement on their WeChat channel reaffirming that they adhere to “One China” policy. UMCSSA referenced the Joint Communiqué that established relations between China and the US in 1979, indicating that by signing the document, the US recognized that Taiwan is a part of China. UMCSSA considered remarks about Taiwan’s autonomy inappropriate within a US university setting. In addition, they also referred to themselves as “the only student organization officially accredited by the Chicago Chinese Consulate at the University of Michigan” (作为密西根大学唯一芝加哥领事馆官方认证的学生组织), a rare public acknowledgment of ties to the Chinese consulate. Nevertheless, the United States maintains a muted position on “One China” policy, opposing either side unilaterally changing the status quo, and has consistently stated its interest in a peaceful resolution.

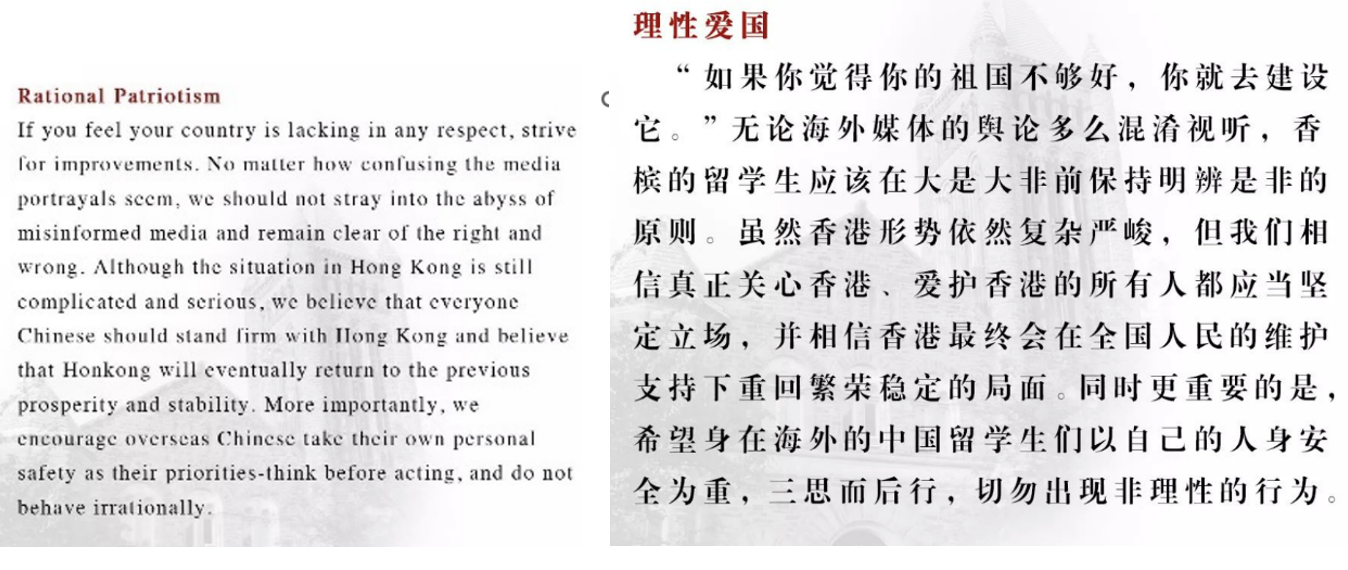

Similarly, China’s “One Country, Two Systems” policy (一国两制) claims sovereignty over Hong Kong. Widespread protests erupted in Hong Kong in 2019 after China introduced a wide-ranging national security law for Hong Kong, which was viewed as an encroachment on the territory’s political autonomy. During this time, the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign CSSA reaffirmed its support for China by publishing an announcement warning Chinese individuals living in Illinois that they should be wary of media misinformation, stand firm with the “One China” principle, think about their personal safety, and embrace “rational patriotism” (理性爱国). The expression “rational patriotism” appears in several posts related to the Hong Kong protests and points to avoiding violence when expressing discontent.

A diversity of opinion about public affairs is largely restricted in China, but academic debate among Chinese scholars overseas is sometimes tolerated. CSSA WeChat channels are now open for debates about China’s population policies, something that would have been unthinkable two decades ago. The CSSA at the University of Wisconsin-Madison frequently posts about academic talks by Yi Fuxian, a Chinese researcher at the university. Fuxian authored “Big Country with an Empty Nest,” a book that warned about the long-term impact of the one-child policy and was banned by the Chinese authorities in 2011. The revised version of Fuxian’s book, “Empty Nest of Great Powers,” is often discussed among Chinese students concerned about the prospects of economic growth stagnation due to population decline, expected to occur around 2030. Such prospects contradict publicized projections that China will generate forty percent of global GDP by 2040, a figure often quoted in CSSA-sponsored networking events.

In 2013, China modified its birth planning policies. Yi Fuxian’s books are no longer banned, but some of his claims are still controversial. His post titled, “2018: A historic turning point — China’s population began to grow negatively” (COCI俱乐部】讲座知识科普 | 2018年:历史性的拐点 — 中国人口开始负增长) is blocked on WeChat. Instead, a notice reads, “This content violates the “Regulations on the Administration of Internet Users’ Public Account Information Services” (接相关投诉,此内容违反《互联网用户公众账号信息服务管理规定》). This indicates that despite a loosening of academic restrictions, opinions challenging the narrative of China’s growth are still prohibited.

These instances of overt censorship are not commonly seen in CSSA groups. It is understood that all content in WeChat is monitored, and CSSA administrators must register with their real identification. Therefore, they usually self-censor anything off-limits. Indeed, extremely sensitive topics such as the forced displacement and cultural erasure of ethnic Uyghurs are never mentioned in WeChat CSSA channels.

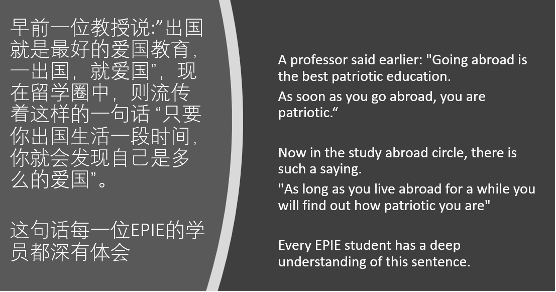

Nonetheless, references to state policies and Chinese Communist Party ideology are frequent in CSSAs’ WeChat posts on a wide range of topics. For instance, an advertisement posted on several CSSAs channels regarding a summer courses program offers a discount for celebrating China’s 70th anniversary. However, before explaining the summer program, the initial paragraphs are devoted to exalting patriotism. This introductory section ends by saying, “Today, we are closer to the goal of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation than at any time in history, and we need to build a strong people’s army more than ever in history.” (今天,我们比历史上任何时期都更接近中华民族伟大复兴的目标,比历史上任何时候都更需要建设一支强大的人民军队). The Chinese nation’s “great rejuvenation” (伟大复兴) is a central theme of Xi Jinping’s vision for China. That subtle reference might go unnoticed by casual readers but certainly would be caught by attentive students and scholars. It refers to a future of economic growth, military power, and expanded welfare under a robust political system led by the CCP. Thus, a strong political message is conveyed, aside from a selling speech for summer courses.

Asian unity against hate

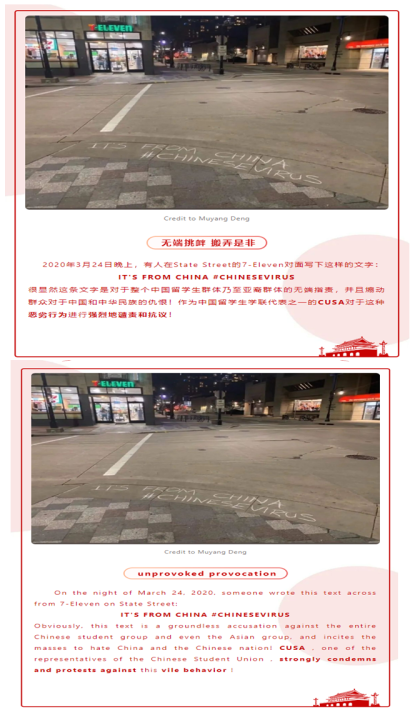

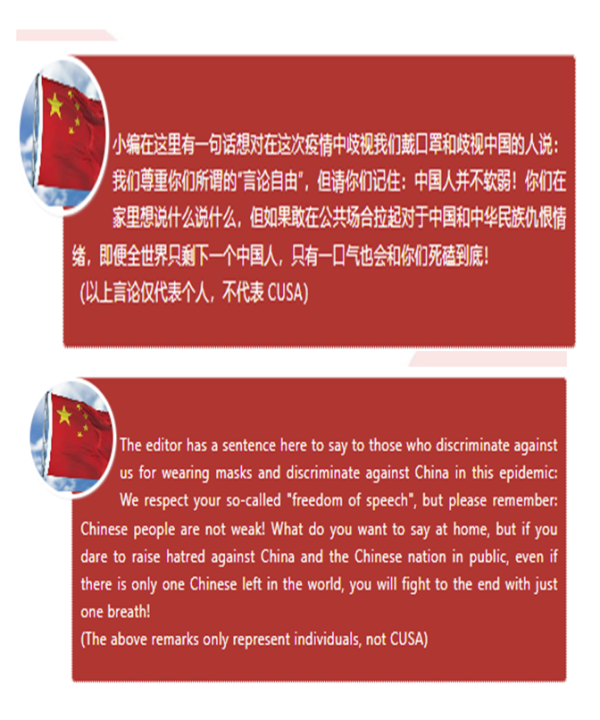

During the timeframe analyzed by the DFRLab, the pandemic of COVID-19 was a major topic in every CSSA group. Besides the disease itself, the students’ groups focused on racial discrimination against Asians brought by the pandemic. On March 24, 2020, Chinese WeChat users who live in Wisconsin, including non-university affiliated individuals, documented graffiti drawn on Madison Streets blaming China for the coronavirus. The University of Wisconsin Chinese Undergraduate Students Association (CUSA) and the University of Wisconsin CSSA called the university to investigate and sanction those responsible for hatred and inflammatory content. The University of Wisconsin promptly addressed their concerns and expressed support for Asian students and staff.

In the aftermath of the Atlanta mass shooting in which multiple Asian women were murdered, several CSSA denounced Asian hate. Indeed, nearly 11,000 hate incidents against Asians and Asian Americans were registered from March 19, 2020 to December 31, 2021, generating solidarity events across the country. As a response, CSSAs called for Asian unity and emphasized unfair bias against China and its government. For example, a strongly worded article posted by the Carnegie Mellon University Chinese Students and Scholars Association protested against anti-Asian hatred:

We have long been law-abiding, friendly to others, and silently fulfilling our obligations and responsibilities as visitors or citizens. However, our self-discipline and tolerance have been ignored and marginalized by mainstream society, making some dominant groups mistakenly believe that we are a weak party, willing to be slaughtered, and dare not resist, even if our values and dignity are despised. Even when trampled, they dare not speak. In the wake of the brutal shooting, some white communities still try to deny our human dignity and existence, even officially denying that the motive was a racial vendetta. However, no matter how some racists and the media whitewash peace, the facts will not change. This Atlanta shooting is an attack on the Asian community, and it is contempt and provocation for the life and human rights of every Asian individual.

长久以来, 我们遵纪守法、友善待人,默默履行自己作为来访者或公民的义务与责任。然而,我们的自律与宽容却换来了主流社会的忽视和边缘化,让某些占主导地位的群体误认为我们是弱势的一方,甘于任人宰割、不敢反抗,即便价值被轻视、尊严被践踏也不敢发声。在残暴的枪击事件后,某些白人社区仍试图否认我们人性的尊严和存在,甚至官方否认该事件的动机是种族仇杀。然而不论某些种族主义者和媒体如何粉饰太平,事实不会改变,这次亚特兰大枪击案是一场针对亚洲社区的攻击,是对每个亚裔个体生命和人权的蔑视与挑衅。这次事件带给我们极大的创伤,因为逝去的生命无法挽回

The post illustrates how the CSSA takes the opportunity to strengthen Chinese identity and nationalism among students, and expose the ills of Western society. This dichotomy is underlying in various topics frequently addressed on CSSA channels, especially in advertisements from Chinese consulates.

A reliable China and an unsafe United States

Besides posts by their admins, CSSA WeChat channels often reshare posts from other verified WeChat accounts. Many of these reshares are promotional content for services and products available to Chinese students. Nevertheless, these seemingly inconsequential promotions usually convey the Chinese worldview. The same discourse strategy is present in most announcements found in CSSA WeChat channels. Usually, the structure is as follows: firstly, praising China; secondly, pointing out the United States’ shortcomings; thirdly, addressing the topic, assuring a clear contrast between Chinese wellbeing standards and a faulty situation in the US.

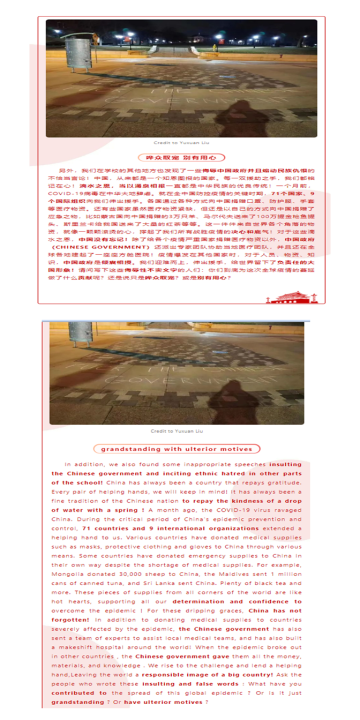

For example, let us look at a post offering COVID19 protection supplies and health services. It starts by praising China’s “victory” in controlling the epidemic inside its territory and its willingness to provide help to foreign countries fighting the pandemic. Secondly, the post points out the weaknesses of the United States’ coping strategies against the pandemic. Only after the comparison is stated does the post begin to refer to services offered.

Another example is a June 2020 article on career services to help students find a job or an internship. It starts by stating that students who chose to return to China at the beginning of the pandemic are happy, but those who decided to stay in the United States are under pressure. Next, the article provides links criticizing the Trump administration’s immigration policies. After that detour, the post does address job hunting challenges and solutions. Several CSSA channels reshared this promotional post, including those from Harvard, MIT, and the University of Michigan.

Likewise, we found many announcements advising Chinese students on measures to protect their well-being considering challenges posed by mental health issues, criminality, and protests. Overall, these posts portray the United States as unsafe, indirectly comparing it with much safer China. During the summer of 2020, protests against police brutality occurred as a response to the murder of George Floyd by a police officer. The Chinese embassy and its consulates issued an announcement, shared by several CSSAs, warning about widespread protests in the United States without contextualization. The San Francisco Consulate issued a statement, later posted by Berkeley CSSA, that stated:

Recently, violent demonstrations have occurred in some areas of the United States, and some shops have been smashed and looted. The Chinese embassy reminds Chinese citizens in the United States to pay close attention to the development of the local security situation, pay attention to the notices issued by the police about parades, demonstrations, and possible riots, and avoid going to dangerous areas. Chinese citizens operating stores should increase their awareness of risk prevention and strengthen security measures at their residences and business premises according to their circumstances.

近期,美国一些地区发生暴力示威,部分商铺遭打砸哄抢。中国驻美使领馆提醒在美中国公民,密切关注当地安全形势发展,注意警方发布的有关游行、示威及可能发生骚乱的通知通告,避免前往相关危险区域。经营店铺的中国公民请切实提高风险防范意识,根据自身情况加强住所及经营场所安保措施 。

Again, the underlying message is that the United States — and the Western world by extension — is violent and unsafe, contrasting with the stable and secure China.

In the end, the primary function of CSSA WeChat articles seems to be giving students orientation on what to stand for publicly on issues adjacent to China’s interests. Speaking out on behalf of China in campus events may not be compulsory, and some Chinese students in the United States agree with Beijing’s policies. In any case, every Chinese student is expected to know how to tell the China story (讲好中国故事), remain loyal to the motherland, and express their patriotism in every circumstance.

This case study is part of a research project on how closed messaging apps are used in the United States. The DFRLab published a Telegram case study in March 2022 and a WhatsApp case study in June 2022.

For additional analysis of CSSA WeChat narratives, please read our companion piece, “How CSSAs reinforce official narratives to expat Chinese students on WeChat.”

Cite this case study:

Iria Puyosa, “WeChat channels keep Chinese students in US tied to the motherland,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), August 31, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/wechat-channels-keep-chinese-students-in-us-tied-to-the-motherland-74daacc6b22e.