Analysis: Why Iranian protesters are embracing Anonymous

The decentralized hacker movement has vowed to free the people of Iran, mirroring chants of protesters on the street

Analysis: Why Iranian protesters are embracing Anonymous

BANNER: A person wearing Guy Fawkes mask, attends a solidarity protest for Mahsa Amini in Washington DC on October 1, 2022. (Source: Reuters Connect/Allison Bailey/NurPhoto)

Since September 17, 2022, Iran has experienced yet another round of mass protests followed by bloody crackdowns. The tragic death of 22-year-old Mahsa “Zhina” Amini in police custody on September 16 sparked the current wave of demonstrations. Amini, originally from Kurdistan province, was on a visit with her family to Iran’s capital city of Tehran when she was detained for “re-education” by the so-called morality police. This highly controversial police unit is responsible for enforcing Iran’s strict, compulsory dress code for women. In detention, she was reportedly beaten in the head and began experiencing concussion-like symptoms. She was hospitalized where she went into a coma and died three days after her arrest. Official reports claim that pre-existing medical conditions led to her death, but Amini’s family has categorically denied these claims and demanded the perpetrators be held accountable.

Amini’s death spurred a wave of nationwide protests across Iran, with women taking the lead. Her death at the hands of a force claiming to safeguard “Islamic values” was seen as symbolic of years of gender-based persecutions and women’s rights violations in Iran. Since September 17, women have been on the frontlines, cutting their hair and removing their headscarves — in some cases, even burning them — to demonstrate their opposition to the Islamic Republic and its misogynist laws. In addition to the feminist outcry, Amini’s Kurdish roots awakened ethnic sentiments beyond Iranian borders and brought together a variety of Kurdish political parties and rights groups, including in Syria and Turkey. Protests that started in the provinces of Tehran and Kurdistan have spread across Iran, including into religious cities, like Mashhad and Qom, which are home to the majority of the Islamic schools and clerics. While the protests have been met with deadly police brutality, people’s resistance and pushback against security forces starkly contrast with previous unrest waves.

Protesters have also taken to social media to voice their anger and attract attention to their cause. According to analysis conducted with Meltwater, a social media analytics tool, Mahsa Amini hashtags in English and Persian have been trending on Twitter since her death on September 16, with more than 289 million tweets. In addition, many Instagram and TikTok influencers helped draw attention to the protests and amplify the cause. In previous protests, Iranian authorities responded by immediately throttling the internet or imposing near-shutdowns, but the recent demonstrations went on for five days before internet restrictions were rolled out. The delay was likely intended to help Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi save face at the United Nations General Assembly, as he was scheduled to give a speech on September 21. As soon as his speech concluded, reports of widespread mobile internet blocks proliferated.

By the evening of September 21, Instagram and WhatsApp — the two most popular international platforms in Iran — were unavailable on mobile networks. Similarly, access to foreign websites was blocked while a limited number of domestic services remained operational. Iran is capable of separating global and domestic internet traffic in large part due to a costly national telecommunication project known as the National Information Network (NIN). Its overarching goal is to substantially cut reliance on international platforms and global internet gateways, and to centralize internet access within the country as much as possible. As nationwide protests have increased in frequency and size in the past years, investments in NIN have started to pay off for the regime. It enables Iran to limit access to international platforms, like social media sites, and fetter the free flow of information on demand. The recent internet disruptions reportedly represent the most severe online restrictions since violent protests broke out in November 2019 over the abrupt rise in gas prices.

Enter Anonymous

Amid these reports of internet restrictions and deadly protest crackdowns in Iran, hacktivist collective Anonymous, known for its activities during Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, pledged its support for the people of Iran. On September 20, a person wearing a Guy Fawkes mask appeared in a video announcing a campaign called #OpIran, and vowed to shut down the government of Iran. A new Twitter account, @anonymousopiran, appeared as well, which has since been promoted by existing Anonymous accounts. As a decentralized collective of volunteers, there is no singular social media account representing all of the movements goals and activities, though some accounts like @youranoncentral and @youranonone have been around for years.

Since the YouTube video first appeared, Anonymous has allegedly hacked more than 1,000 CCTV cameras across Iran and launched distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks against websites of multiple state bodies, including the Central Bank of Iran; official websites of the executive branch, including president.ir; the official portal of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei; and the website for the Telecommunications Company of Iran (TCI), a state-owned telecom entity. Anonymous also leaked the purported bank information of government officials and phone numbers of members of parliament — all in the name of #OpIran and Mahsa Amini.

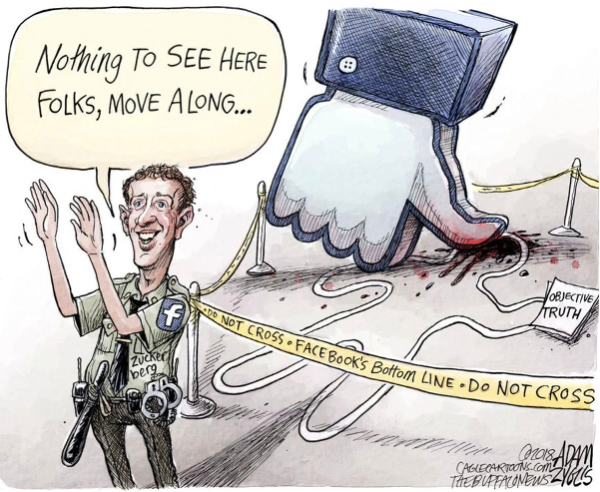

Protesters welcomed the actions of Anonymous and began to include #OpIran in their tweets and Instagram posts. At the time of writing, #OpIran had been tweeted more than 83 million times alongside variations of Amini’s name in Persian and English, including #MahsaAmini, #Mahsa_Amini, and #مهسا_امینی. In addition to these hack-and-leak activities, Anonymous blamed Instagram for content takedowns related to the Iran protests and accused WhatsApp of blocking Iranian phone numbers, a rumor that was widely circulated online. Both platforms are owned by Meta, parent company of Facebook. Anonymous pressing the matter, coupled with public outrage, prompted WhatsApp to issue a statement insisting that it was not blocking Iranian numbers and pledging to keep the service running for all Iranians.

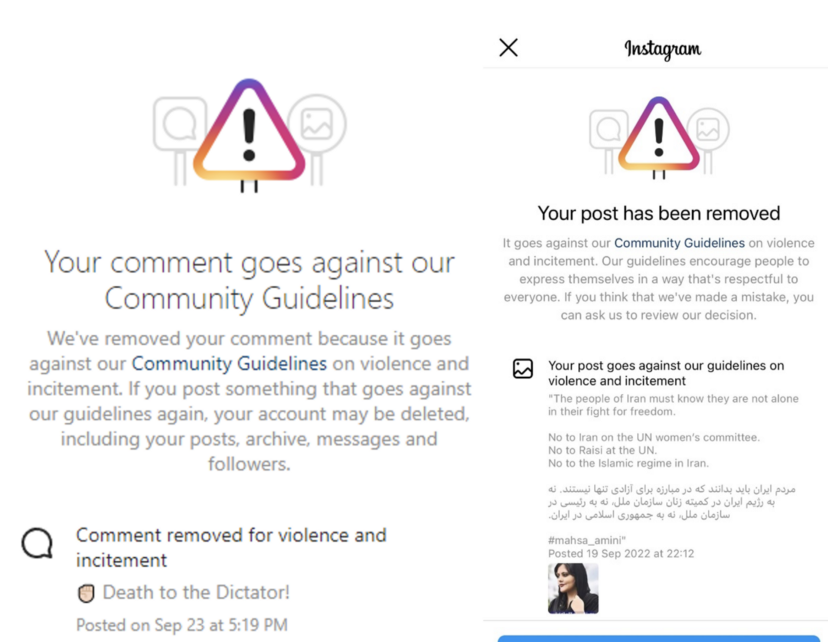

As Iranians turned to Instagram, one of the only major social media platforms that is not blocked in the country, to spread their message and document police brutality, Instagram removed certain posts related to the protests. In one instance, an Instagram user who commented, “✊ Death to the Dictator!” had their comment removed for violating the guidelines on violence and incitement. As previously reported, the phrase “Death to X” is a protest slogan with a long history of use in Iran, and not generally regarded by Iranians as a literal death threat. In another case, a post with the caption, “The people of Iran must know they are not alone in their fight for freedom. No to Iran on the UN women’s committee. No to Raisi at the UN. No to the Islamic regime in Iran,” was also removed for violating Instagram guidelines on violence and incitement.

The recent protests are not the first time Anonymous has targeted the Iranian government. In June 2009, amid the Green Movement protests that emerged in response to the disputed re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Anonymous launched an earlier version of Operation Iran (OpIran) — in this case a DDoS campaign targeting government websites and government-affiliated organizations. Two years later in February 2011, as Iranians took to the streets to support the Arab Spring, Iran sought to suppress the protests through mass arrests, renewed censorship, and jamming satellite news channels. In response, OpIran was resurrected, launching DDoS attacks against government websites, including the websites of the Supreme Leader and the president. Later that year, in the run-up to the anniversary of the 2009 Iranian presidential election, Anonymous leaked more than 10,000 emails from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that contained visa requests and passport images of non-Iranians. However, these incidents were not widely noted by Iranians at the time.

What makes Anonymous appealing to Iranians

While Anonymous pursues tactics similar to its previous activities in Iran, the traction they have recently garnered from Iranians is different. Anonymous has vowed to shut the Iranian government down and free the people of Iran, mirroring the chants of protesters on the street. As protests persist in Iran, Anonymous shows its solidarity by taking down new targets and leaking sensitive information, inspiring protesters further. In other words, the continuous actions on one side feed into the other. For the leaderless and grassroots movement currently taking on the Iranian regime, Anonymous’s actions are meaningful as they come from an equally leaderless and hierarchically flat collective, claiming to hold those in power accountable with cyber-enabled tactics. The absence of alternatives combined with persistent actions and powerful optics has created a sense of trust and solidarity between many Iranian protesters and Anonymous.

Anonymous is not the only hacktivist group attacking the Iranian government. Hacker group Edaalate Ali (“Imam Ali’s Justice”) defaced the website of the Morality Association and leaked the personal information of multiple members of the morality police. But Anonymous is the only group that has managed to merge its campaign with the protesters. Concurrent use of OpIran and Mahsa Amini-related hashtags shows that the two streams have embraced one another to unite for better amplification and awareness. Other groups like Gonjeshke Darandeh (“Predatory Sparrow”) have increasingly targeted Iranian entities and infrastructure, particularly over the past two years. However, the different circumstances under which these groups have emerged, coupled with speculation about a possible connection to state actors using hacktivism for covert operations, impedes trust-building and affects traction. Meanwhile, Anonymous benefits from name recognition and a much longer history. This comes despite the legal consequences it has faced for past activities like the 2010 PayPal hack.

Iranians are facing a near-total internet shutdown alongside content moderation complications that impede their activities. Frustrated with both policies for vastly different reasons, protesters found an ally in Anonymous. It not only hacks the government but also voices Iranians’ frustration with Big Tech policies and practices in a sensational way. In addition to attacking websites, Anonymous has called out Iranian tech companies known to work closely with the Iranian intelligence apparatus and pledged to leak the personal information of their executives. The naming and shaming approach adds fodder to public outrage and creates a sense of suspense and anticipation about what Anonymous might do next.

Expanding the possibilities, Anonymous style

It is too early to tell where the protests might lead, but the number of tweets referencing Mahsa Amini and/or #OpIran is already declining. This can partly be attributed to internet disruptions and the absence of coordinated protest leadership that can guide the movement to the next level. Even though there are calls for strikes throughout the country — several educational institutions have indeed done so — it remains to be seen if a nationwide general strike is achievable and if it could survive the police brutality that would undoubtedly follow.

In these volatile circumstances, Anonymous’s actions continue to mirror the boldness of protesters by helping boost morale — particularly for those that still have access to the internet and follow the latest developments. Anonymous hack-and-leak tactics may not impair the government in the long term, but they extend the frustration of protesters to the virtual doorsteps of a highly unpopular regime and encourage solidarity with the public. Like the protests themselves, however, these online measures lack concrete direction and leadership, and remain contingent upon whatever leakable materials Anonymous can get its hands on. Nonetheless, they have expanded the possibilities at the intersection of civil disobedience and cyberattacks to an irreversible point. What comes next remains to be seen.

Simin Kargar is a Non-Resident Fellow at the DFRLab. She is currently a doctoral researcher at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University.

Cite this case study:

Simin Kargar, “Analysis: Why Iranian protesters are embracing Anonymous,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), October 13, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/analysis-why-iranian-protesters-are-embracing-anonymous-2b2bc1340296.