Potentially hijacked Twitter accounts promote Sudanese paramilitary force

Over 900 accounts appear to boost tweets from the RSF and its leader, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemetdi” Dagalo, as armed conflict sweeps across Sudan

Potentially hijacked Twitter accounts promote Sudanese paramilitary force

Share this story

Deputy of Sudan’s Military Leader, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, speaks at a ceremony to sign the framework agreement between military rulers and civilian powers in Khartoum, December 5, 2022. (Source: Reuters/El Tayeb Siddig)

At least nine hundred potentially hijacked Twitter accounts are liking and occasionally retweeting content posted by Sudan’s Rapid Support Force (RSF) and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the head of the RSF and deputy leader of Sudan’s ruling council. Following the outbreak of violent conflict on April 15, 2023 between the RSF, a paramilitary group administrated by Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service, and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the accounts have continued to amplify RSF content.

The DFRLab identified the accounts accounts after scraping the user data for any account that liked tweets recently posted by Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti, and by the RSF. The DFRLab could not conduct similar research on the SAF or SAF leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, as neither the SAF or al-Burhan had active Twitter accounts at the time of data collection.

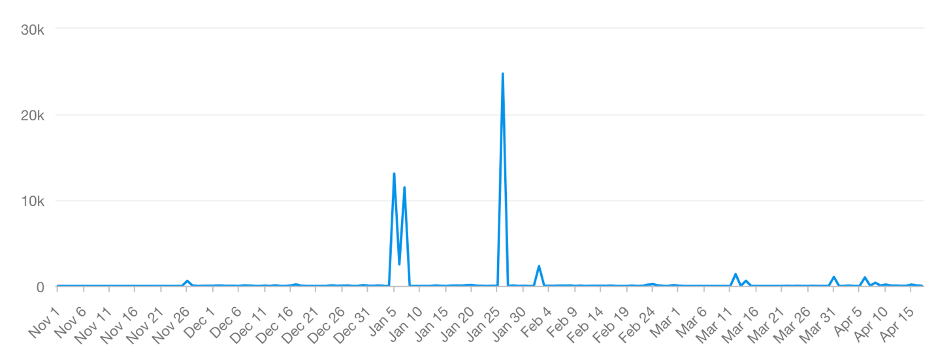

The accounts followed a similar pattern: after remaining inactive for years, many became active again in December 2022, tweeting a string of characters lifted from Wikipedia pages, then boosting tweets from Hemedti and the RSF. The accounts also posted inspirational quotes in Arabic, potentially to make the accounts look more authentic.

Many of the accounts displayed evidence of having previously been operated by real users, including links to personal Instagram accounts and tweets with identifying information. Although they worked to promote the RSF and Hemedti, almost none of the nine hundred identified accounts followed either the RSF or Hemedti on Twitter.

However, from March 30 onwards, the pattern of behavior changed as the accounts started liking content about the RSF and Hemedti posted by journalists, news outlets, and other accounts with a few thousand followers.

The rivalry between the RSF and SAF twice delayed the formal adoption of a framework deal, intended to be signed on April 6, 2023, which would have led to the creation of a civilian-led transitional government on April 11. If the agreement had been signed, it would have seen the RSF integrated into the SAF. Instead, tensions rose again between the two sides after RSF mobilizations led the SAF on April 13 to warn of conflict. On April 15, the SAF and RSF began engaging in heavily armed conflict in multiple locations across the country, resulting in civilian deaths. At the time of publication, fighting between the two groups continued.

As tensions between Hemedti and al-Burhan escalated, the accounts investigated by the DFRLab continued to like content on Twitter. It is possible the potentially hijacked accounts are being used to make the RSF and Hemedti appear more popular than they actually are on the platform by boosting their tweets and appealing to a more international audience via English-language tweets, while simultaneously promoting the group’s narrative surrounding the current conflict, which claims that the RSF responded to an attack initiated by the SAF and that al-Burhan is a radical Islamist.

Some of the accounts in the network identified by the DFRLab were previously investigated by Beam Reports, a Sudanese media outlet focused on fact-checking and disinformation investigations. Beam Reports has documented other examples of potentially fake or inauthentic accounts used to promote the RSF on multiple social media platforms. In October 2021, the DFRLab reported on a Facebook network engaging in coordinated inauthentic behavior to promote the RSF. The network, which had links to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), was removed by Facebook for “coordinated inauthentic behavior on behalf of a foreign or government entity.” Saudi Arabia and the UAE have long-standing relationships with Hemedti and the RSF.

Wiki tweets

Using Twitter’s API, the DFRLab downloaded 3,612 tweets from the official RSF Twitter account and 362 tweets posted by Hemedti’s account, totaling 3,974 tweets. From there, the DFRLab collected the user handle and unique user ID of every account that liked at least one of the 3,974 tweets. After removing duplicate accounts that liked more than one tweet from the RSF or Hemedti, a total of 4,882 accounts remained.

(While utilizing the Twitter AP, we noted some inconsistencies between the data publicly visible on Twitter’s website and the data collected via API. For example, in a number of cases, Twitter’s website would show that particular account had liked a tweet by the RSF, but this was not reflected in the collected API data. As a result of these current inconsistencies between Twitter’s website and API, it is likely that the total number of accounts we identified is an undercount.)

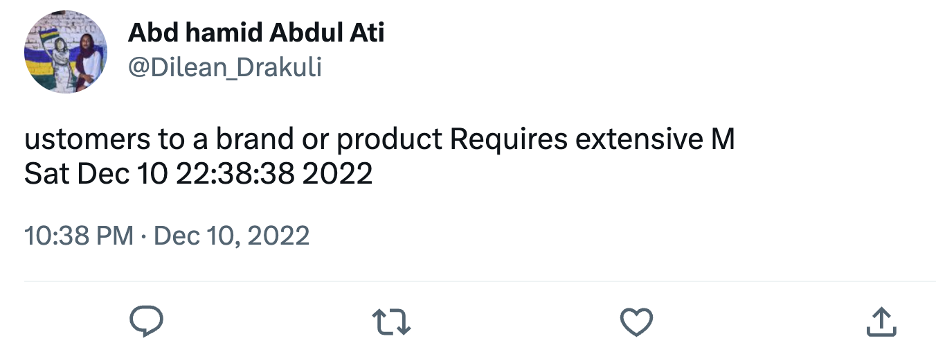

A manual review of assorted tweets posted by the 4,882 users revealed that some very old accounts, most of which had been dormant for many years, suddenly began tweeting between December 2022 and February 2023 what appeared to be a random combination of words and a date. One account, for example, tweeted the seemingly nonsensical phrase “ustomers to a brand or product Requires extensive M Sat Dec 10 22:38:38 2022.”

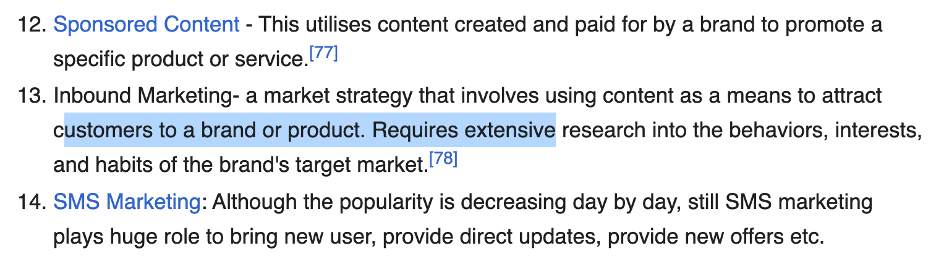

At least nine hundred accounts in the dataset that posted tweets similar to the above example. While text itself varied, a Google search for a selection of tweets revealed that it had been lifted directly from Wikipedia pages. One page on digital marketing was used extensively.

The accounts were used to share a fifty-character slice of text, seemingly at random, from different Wikipedia pages. The string of text was scrubbed to remove all non-alphanumeric characters, including commas, periods, and brackets. If the string happened to start or end with a space, the space would also be trimmed. As a result, some tweets contained precisely 50 characters, while others contained fewer than fifty characters. In the above example, the period between the words “product” and “Requires,” which can be seen in the Wikipedia entry, was removed from the tweet, resulting in a string with forty-nine characters instead of fifty. In each tweet, the Wikipedia string was followed by an upper case “M,” a line break, and the exact date and time the tweet was posted.

Most of the accounts had a low number of followers, with more than 800 of the 900 accounts having fewer than five followers and over 400 accounts having no followers.

Boosting the RSF and Hemedti

It appears the primary goal of the accounts is to boost content about the RSF and Hemedti on Twitter. Initially, the likes and retweets exclusively occurred on content posted by the official accounts of the RSF and Hemedti; however, as tensions between the RSF and SAF escalated, the accounts began to like content about Hemedti posted by Sudan’s state news agency, journalists, and media outlets.

The accounts first deviated from their pattern on March 30, when a number of accounts liked a tweet by the Sudanese branch of Asharq News, a Saudi-owned Arabic news channel. The tweet summarized a thread posted by the RSF in which the paramilitary group confirmed its commitment to integrating into the army and creating a single armed force, and reiterated that the RSF and SAF have a strong relationship.

On April 1, some of the accounts in the network liked a tweet that read, “Our enemy in the first place is the Kizan army, not the rapid support, our enemy in the first place is the Kizan, not the Janjaweed….” Kizan refers to individuals from former President Omar al-Bashir’s National Congress Party and those supportive of the former regime, while Janjaweed is a reference to the Arab militia that grew into the RSF.

Another reference to Kizan occurred on April 13, two days after the civilian-led transitional government was expected to be implemented. A subgroup of accounts tweeted the hashtag #أي_كوز_ندوسو_دوس, which roughly translates to “Every Koz, we will trample over them.” Koz, in this instance, is used as the singular of Kizan. The accounts tweeted the hashtag just after 3:00 am Central Africa Time. Since then, the subgroup has not liked or tweeted any other content.

Occasional retweets and replies

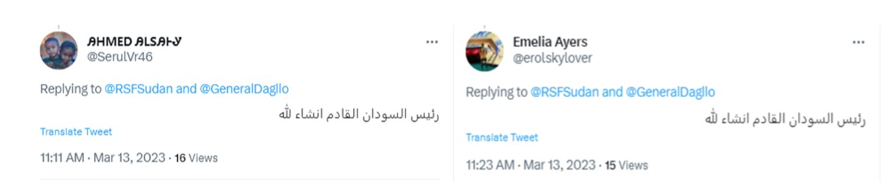

In addition to liking RSF and Hemedti content, several accounts focused on retweeting one specific RSF tweet about a visit by an RSF general to a children’s hospital. The tweet received a total of 105 retweets, with 81 retweets coming from the identified accounts. In a separate instance, two accounts replied to two tweets by the RSF about Hemedti’s recent visit to Eritrea. They both included the same text, which read, “Sudan’s next president, God willing.”

Since the outbreak of armed conflict between the RSF and SAF, the network of accounts has primarily focused on amplifying the narrative spread by the RSF.

Indicators of potentially hijacked Twitter accounts

A number of indicators point to the possibility that many of the nine hundred accounts identified by the DFRLab were originally operated by legitimate users and subsequently hijacked and repurposed.

Previous usage

Many of the accounts contained evidence indicating the accounts once belonged to unique users. This included links to personal Instagram accounts, posts containing photographs, and tweets in different languages.

For example, the account @asyrafmanja27 tweeted five times in June 2014 in both English and Malay. The account’s first tweet claimed the account’s owner was named Asyraf and was from Johor, a state in Malaysia. It posted a link to an Instagram page, as well as original photographs. Then, after going dormant in June 2014, the account became active on December 11, 2022, posting a string of text from the digital marketing Wikipedia page, followed by a number of posts in Arabic.

Mismatched usernames and screen names

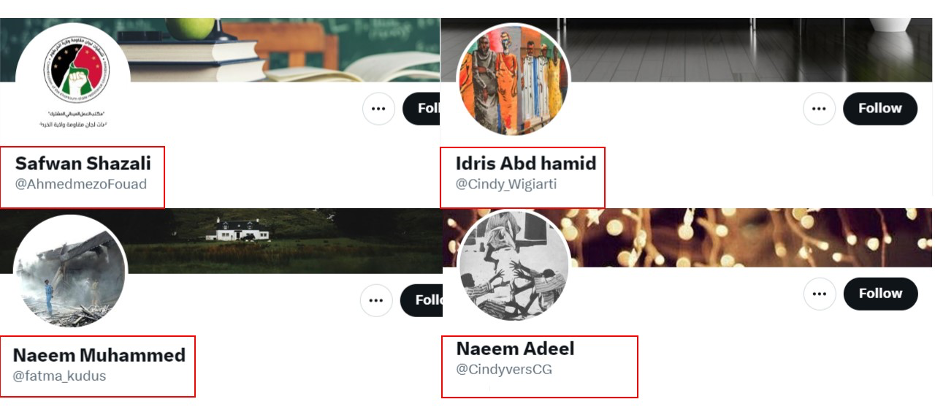

Another factor pointing to a potential hijacking of previously legitimate accounts was the presence of mismatched usernames and display names. Although it is possible to change a username, also known as a user handle, usernames must be unique, making the process of changing a username slightly more involved than changing a screen name, which can be any string of text, including text used elsewhere.

Some accounts had Arabic display names and non-Arabic usernames, while others had usernames typically associated with women and display names typically associated with men. For example, the account @AhmedmezoFouad used the display name “Safwan Shazali,” while the account @Cindy_Wigiarti used the display name “Idris Abd hamid.”

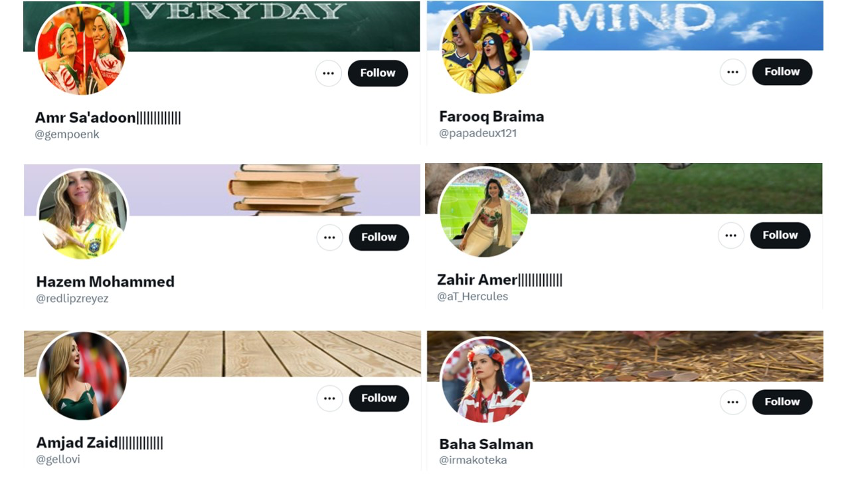

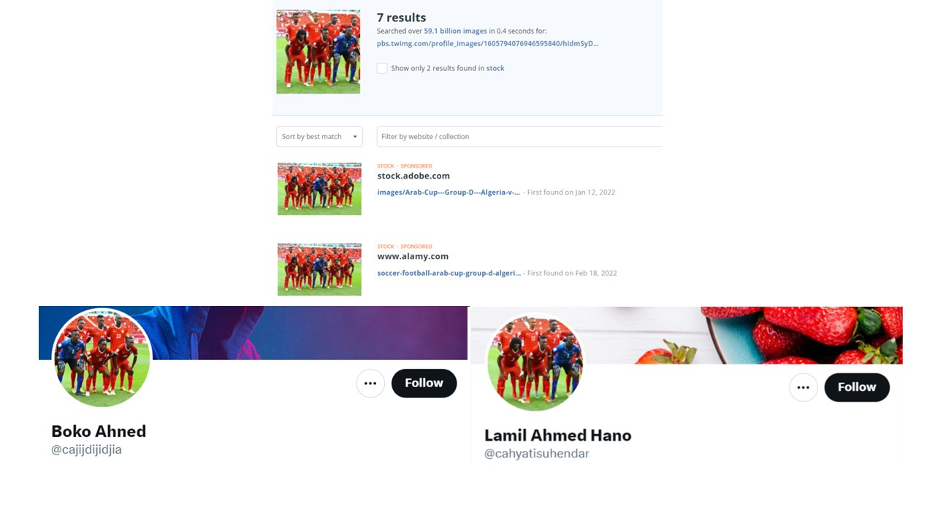

Generic profile pictures

The DFRLab noticed several accounts using the same types of generic profile pictures. Many accounts used publicly available photos of Sudanese protestors, generic images of plants, or pictures of football players or football fans. The images of football fans were often women, even though some of the accounts used display names typically associated with men.

In addition, a reverse image search revealed that two accounts, @cajijdijidjia and @cahyatisuhendar, used the same picture of Sudan’s national football team participating in the 2021 FIFA Arab Cup. However, each account cropped the image of the team differently so they present as two similar but different pictures.

Suspicious posting times

Another indication of suspicious behavior is found in the accounts’ posting patterns. Although not all nine hundred accounts had similar posting patterns, groups of accounts appeared to post similar content within a short span of time, sometimes within the same minute. In one example, a group of six accounts tweeted within the same minute, once on February 26 and twice on March 1. All the accounts tweeted a Quranic verse or an Islamic saying on February 26, followed by a generic picture and an inspirational quote on March 1. A total of thirty-seven accounts followed this pattern, tweeting within four minutes of each other. It appears as if generic quotes were used to try and make the accounts appear more authentic.

A potentially larger network

A query on Meltwater Explore for the string posted by user @Dilean_Drakuli, “ustomers to a brand or product Requires extensive M,” revealed that it was posted by 614 users between November 1, 2022, and April 17, 2023. While the string itself was unchanged, the date and time contained in each tweet corresponded with the date and time each tweet was posted. When the DFRLab originally conducted this query on March 15, 2023, the number of accounts was much higher, indicating some of the accounts in the larger network may have already been removed.

The network of potentially hijacked accounts identified by the DFRLab to be promoting the RSF and Hemedti appear to be a small portion of a larger network. The Wikipedia strings tweeted by the network were tweeted by hundreds of other accounts.

Accounts that appear to be a part of this larger network did not always include an upper case “M” after the Wikipedia string. Instead, it seems as if different letter combinations were used as identifiers.

The current conflict between the RSF and SAF is one of the first in Sudan’s recent history that has taken place without internet access being shut off. The two warring sides have attempted to take control of the narrative online, while simultaneously taking control of the country through violence. On Twitter, at least, it appears as if some of the accounts engaging with Hemedti and the RSF may not be authentic.

Cite this case study:

Tessa Knight, “Potentially hijacked Twitter accounts promote Sudanese paramilitary force,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), April 18, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/04/17/potentially-hijacked-twitter-accounts-promote-sudanese-paramilitary-force.