A snapshot of Turkey’s information environment prior to the presidential election

Rumors, misinformation, and unsupported allegations swirled ahead of the first round of voting

A snapshot of Turkey’s information environment prior to the presidential election

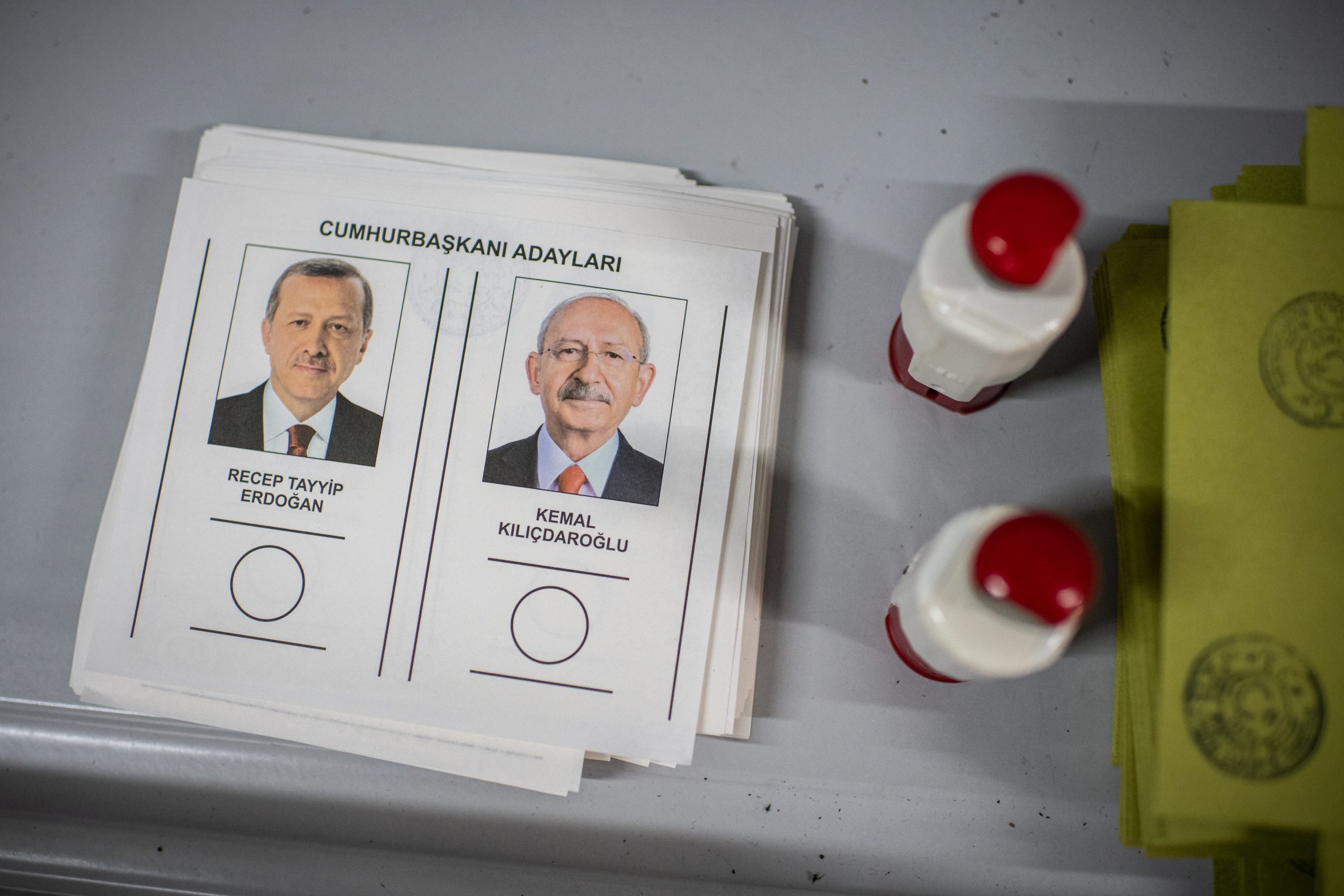

BANNER: A presidential runoff ballot at a polling station in Istanbul featuring incumbent president Recep Tayyip Erdogan and main opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu, May 28, 2023. (Source: Reuters Connect/Diego Cupolo/NurPhoto)

On May 14, 2023, millions of Turkish voters went to the polls for presidential and parliamentary elections, resulting in no presidential candidate receiving an outright majority. As a consequence of this, a run-off between incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and opposition leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu took place on May 28. Erdoğan secured another five years in power by receiving 52.16 percent, while Kılıçdaroğlu received 47.84 percent.

In 2017, Erdoğan’s coalition successfully passed a constitutional referendum switching Turkey’s governmental structure from a parliamentary system with a prime minister appointed by the legislature to a presidential system that consolidated executive powers in the office of the president. Voters re-elected Erdoğan to this now-strengthened presidency the following year.

To compete against Erdoğan in 2023, six opposition parties created an alliance and consolidated around the candidacy of Kılıçdaroğlu, the head of the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). This “Nation Alliance,” as it became known, promised to restore the parliamentary system, reintroducing limits on presidential power.

In the first round of elections, other presidential candidates included nationalist candidate Sinan Oğan, backed by the ATA Alliance, and Muharrem İnce, who entered the presidential race as a candidate representing his Homeland Party. On May 11, İnce withdrew from the presidential race. İnce still received 0.43 percent of the presidential vote during the first round, as the ballots had been published prior to his announcement, while Oğan received 5.17 percent.

In the weeks leading up to the first-round election on May 14, the DFRLab closely monitored the information environment in Turkey. Below, the we cover some of the main narratives that potentially affected voters’ opinions.

Rumors around misprinted ballots, ballot-stuffing, and observer registrations

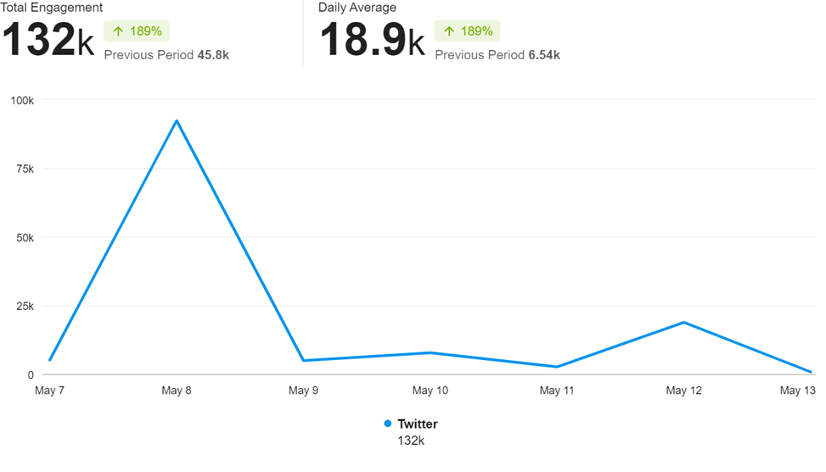

Misinformation about ballots circulated prior to election day. Ahead of Turkish citizens residing abroad casting their ballots on May 9, a rumor spread regarding a misprinting on some ballots. Turkish citizens in the Netherlands noticed a black dot under Erdoğan’s name and highlighted it on social media. This morphed into a baseless conspiracy theory that any votes using those ballots for anybody other than Erdoğan would be rejected. The claims went viral on Twitter immediately prior to more than three million Turkish citizens residing abroad heading to the polls. In response, Turkish officials denied the rumors in a statement.

On May 14, a video circulated online allegedly showing a person voting for Erdoğan on multiple ballots in the city of Şanlıurfa in southeastern Turkey. In a Twitter post, the video circulated alongside claims that election observers had been attacked. Şanlıurfa officials denied the claims and announced judicial action against social media users who had posted the video. Similar videos allegedly from Şanlıurfa also circulated online, but the DFRLab could not verify their provenance or accuracy.

Additionally, local media outlets and journalists reported voting disruptions in Gaziantep. The Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) accused Vatan Partisi (the Patriotic Party, known for its strong pro-Russian and pro-Chinese positions) of registering HDP voters, mostly consisting of older or illiterate individuals, to serve as ballot box observers without their consent, which would prevent them from voting. Though the HDP is facing a potential shutdown for its alleged ties to terrorism, the party participated in the parliamentary elections under the banner of the Green Left Party, while jailed HDP co-leader Selahattin Demirtaş supported Kılıçdaroğlu’s candidacy.

Accusing opposition candidates of receiving terrorist support

With an unstable Syria along Turkey’s southern border and Syrian refugees dominating political discourse, national security and public safety have been a prevailing concern for Turkish voters this election, more so than the country’s current economic crisis or increasingly curtailed fundamental rights. As such, messages tying any candidate to terrorist groups were likely to resonate during this election and scare off voters.

The dominant narrative of the first round of the 2023 elections alleged that the CHP, the Nation Alliance, and Kılıçdaroğlu received support from terrorists – in particular, cooperating with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which the United States and the European Union have designated as a terrorist organization.

At a rally on May 7, Erdoğan presented a deliberately misleading video that edited together two unrelated clips. The video starts with Kılıçdaroğlu calling on his supporters to vote, seemingly from an official campaign promotional ad, and saying “Let’s go to the ballot box together.” The video then cuts to Murat Karayilan, a PKK founder, who is seen clapping and saying “Let’s go” at a separate event. Local fact-checkers and German news outlet Deutsche Welle debunked the video, finding that the footage of Karayilan came from a much earlier video completely unrelated to Kılıçdaroğlu’s original campaign video.

The idea that Kılıçdaroğlu and the opposition received support from terrorists was further amplified in speeches and by pro-government media outlets. For example, on May 6, Devlet Bahceli, head of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), threatened the opposition. “On May 14, a sad end waits for the CHP and Nation Alliance…These traitors will either receive aggravated life sentences or bullets in their bodies,” he stated. In the same speech, Bahceli repeated the same accusations, declaring without evidence, “Kılıçdaroğlu’s allies are terrorists, and his partners are enemies of Turks.”

Additionally, images circulated of fraudulent advertisements featuring the CHP logo, a photo of Kılıçdaroğlu, and text that falsely claimed he had pledged to release jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan. The falsified ad circulated widely on multiple platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram. A reverse image search on Google easily found the original campaign ad, which contained no references to Öcalan.

Similar brochures were distributed on the street as well. CHP Istanbul chair Canan Kaftancıoğlu alleged that the AKP was behind the fabricated pamphlet, saying that the CHP had allegedly identified two of the distributors as being members of AKP’s youth branch; this claim remained unverified at the time of publishing, however. Also, journalists reported on different fake pamphlets that appeared on the streets with other fabricated Kılıçdaroğlu promises.

Using manipulated or fabricated campaign pamphlets to undermine opponents is not a new practice in Turkey. During the 2018 presidential elections, for example, fake campaign brochures circulated both online and offline.

Adding to this narrative, another video shared across platforms depicted a ballot with Kılıçdaroğlu’s picture over a cartridge of bullets featuring logos of terrorist or terrorist-affiliated groups alongside two political party logos. The video then shows the ballot stamped for Kılıçdaroğlu, followed by a new bullet loading into the cartridge, implying that support for Kılıçdaroğlu equates to arming terrorists.

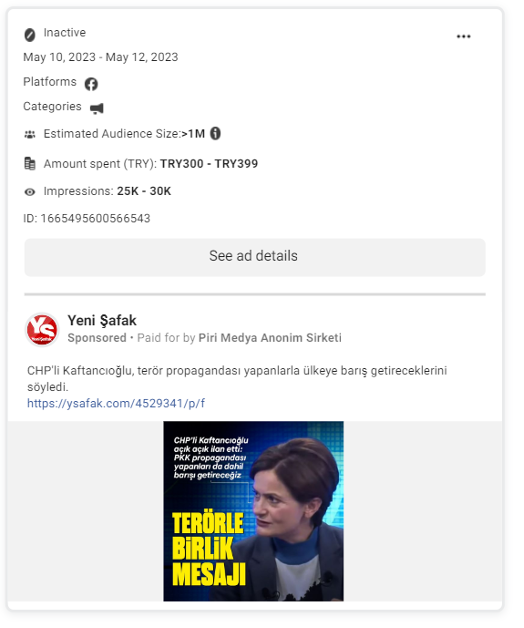

The DFRLab searched Meta’s Ad Library for advertisements referencing the PKK. One of the resulting posts showed Kaftancıoğlu in a video that was manipulated to falsely portray her as supporting terrorists. In particular, she can be seen supposedly declaring, “We will bring peace to this country, including those who make propaganda for a terrorist organization.” In the original video, however, Kaftancıoğlu can be seen saying in full:

This election will end in the first round. This election will end in the first round, so that we can start to build a Turkey where 86 million can live together, starting on May 15. Let’s say it to laugh. Our citizens should be prepared on the morning of May 15, more than 55 percent of Turkey’s population could be declared to be terrorists. But don’t worry, never fear. Whatever they do. After May 15, we, 86 million together, will bring peace to this country, including those who made propaganda for a terrorist organization while ruling this country. They will not be slandering us again.”

Other ads published similar narratives suggesting cooperation between opposition parties and terrorists.

These narratives had real-life consequences as well. On May 7 during a rally in Erzurum, protestors threw stones at CHP vice presidential candidate Ekrem İmamoğlu, leaving dozens injured, including a child. İmamoğlu blamed police for failing to provide safety. In video footage recorded at the event, protesters could be heard shouting the slogan, “The bastards of Apo [Abdullah Öcalan] cannot demoralize us.”

Candidate withdraws from presidential race after kompromat video released

On May 11, presidential candidate Muharrem İnce publicly withdrew from the race after a suspicious Twitter account impersonating writer Ali Yesildag (@ali_yesilda), posted alleged sex tapes of İnce to the platform. In his statement, İnce denied that he had made any such tapes. The real Ali Yesildag previously reported alleged corruption within the ruling party and by Erdoğan; he is also the brother of Hasan and Zeki Yesildag, owner of media consortium Turk Medya Group. Yesildag has repeatedly denied maintaining any social media accounts, including the Twitter account in question, and the identity of the account’s operator remains unknown.

Hours after İnce pulled out of the presidential race, Kılıçdaroğlu blamed Russia of meddling in the elections in the form of “montages, conspiracies, deep fakes, and tapes,” and warned them that they were risking their friendship with Turkey. Kılıçdaroğlu posted these accusations to Twitter in Turkish and Russian but did not provide any evidence to support his assertions. Journalist Ragıp Soylu from Middle East Eye asked a senior opposition official why Kılıçdaroğlu suspected Russian interference. “There are some Russian companies that operate worldwide helping Erdoğan campaign here in Ankara,” the anonymous official alleged. They did not reveal the name of company, however, and the Kremlin rejected the accusations.

Indeed, the account publishing the alleged sex tapes did not have any obvious links to Russia. Social media researcher Dr. Tugrulcan Elmas revealed that, after looking at the account history using the same Twitter user ID number, the account had changed its name multiple times; it had also labeled several journalists as “traitors” and published disinformation regarding wildfires in Turkey. Fact-checking initiative Malumatfurus previously debunked the same Twitter ID in 2022 when the account was impersonating a Turkish poet.

While the repeated profile changes indicates that the @ali_yesilda account was likely inauthentic, it attempted to suggest otherwise by posting authentic videos of the real Ali Yesildag that were originally published to YouTube by the channel Cevheri Güven. After attempting to create a veneer of credibility, the account then pivoted to release more salacious content, including alleged sex tapes featuring İnce. (The authenticity of the sex tape remains unverified.) Beyond İnce, the account promised to release tapes purporting to featuring other political figures in Turkey, including ones aligned with the AKP.

Despite seemingly violating Twitter’s terms of use around privacy and explicit content, the account remained live until election day. On May 11, İnce announced that he was withdrawing from the presidential race; that same day, a pre-election polling survey released by polling firm Konda suggested he was drawing just 2.2 percent of the vote. İnce said that his support had fallen following the publication of the reportedly fabricated tapes and that he did not want the opposition to hold him responsible if Kılıçdaroğlu lost. He also stressed that the state could not protect his reputation. Despite withdrawing from the race, it was too late to have his name removed from the ballot as they had already been printed and Turkish citizens abroad had already voted. His party remained in the parliamentary race.

While the account behind the kompromat remained active, a day before the election, Twitter announced that it had restricted access to certain content and accounts in Turkey, without providing further details. After reactions from users in the country, Twitter published court orders it had received from the Turkish government on May 15. Accounts that had allegedly targeted the AKP were on the list, including accounts that had posted videos of Ali Yesildag accusing the AKP government of corruption. Meta also published content restrictions on “110 items containing videos and audios of Ali Yesildag making allegations of various crimes and corruption by the government.” Both social media companies received court decisions under Article 8/A of Turkish Law No. 5651 on the Regulation of Broadcasts via Internet and Prevention of Crimes Committed through Such Broadcast.

Pro-government media targeted independent fact-checkers

In October 2022, Turkey passed legislation ostensibly to curtail the spread of disinformation that granted the government greater control over social media and news websites, the practical application of which has stifled freedom of expression. Article 29, called the “censorship law” by journalists, says that those who spread false information online about Turkey’s security to “create fear and disturb public order” would face a prison sentence of one to three years. According to an Anadolu Agency report on May 11, after criminal complaint of the presidential communications directorate, the Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office launched an investigation into social media accounts allegedly spreading coordinated disinformation that had reached some 40 million social media users.

This report came after pro-government media outlets and newspapers published allegations on May 5 claiming the CHP employed “troll armies” with 40 million Twitter followers. But these reports did not provide any methodology or findings that corroborated any charges of coordinated behavior. According to a DFRLab query of the social media monitoring tool Meltwater Explore, the hashtag “#KemalinTrolOrdusu” (“Kemal’s troll army”) was mentioned 20,314 times on Twitter that same day.

On May 14, pro-government, Islamist newspaper Yeni Akit published a report targeting independent fact-checking organizations. “While the Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office launches an investigation into accounts spreading coordinated disinformation,” it wrote, “platforms such as [fact-checking organizations] ‘Teyit Org’ and ‘Dogruluk Payi’ raise great suspicion.” The report also stated, “Founders of these platforms are known to have relationships with FETO [a group associated with cleric Fethullah Gulen], PKK, and other radical left organizations.” The DFRLab found other reports from pro-government media outlets targeting fact-checking organizations with allegations of terrorism and connections to Hungarian-American businessmen and frequent subject of antisemitic conspiracy theories George Soros, photos of whom were used as banner images for stories.

Anti-LGBTQI+ rhetoric

One of the first promises Kılıçdaroğlu made as a candidate was to rejoin the Council of Europe’s Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, commonly known as the Istanbul Convention, which Erdoğan withdrew Turkey from in 2021 amid a proliferation of disinformation, hate speech, and misleading narratives. In order to justify its decision, the Turkish government claimed that the Istanbul Convention “normalizes homosexuality” and is “incompatible with Turkey’s social and family values.” According to a report from Turkish nongovernmental organization AG-DA, pro-government media outlets amplified anti-convention narratives, starting by targeting gender equality. “After the head of Religious Affairs [Diyanet] Ali Erbaş targeted the LGBTQI+ community during the Friday sermon and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan embraced this statement, the focus of the discussions became LGBTQI+,” it reported. “The concept of gender equality in general, the Istanbul Convention in particular, and the allegation of ‘deviance’ attributed to [members of the] LGBTQI+ [community] by these media outlets have been used to ‘stigmatize’ any thought outside of the government.”

During the 2023 election campaign, Erdoğan targeted the LGBTQI+ community at rallies in fourteen cities, with an emphasis on family values in his speeches, according to independent Turkish news outlet Gazete Duvar. At one of these rallies, Erdoğan declared that all of the parties comprising the Nation Alliance to be “pro-LGBTQI+.” He added that “AKP, MHP, People’s Alliance are against the LGBTQI+ community,” and tied the LGBTQI+ community to the opposition, arguing “they are against our holy family structure.”

Erdoğan’s government ministers also made similar statements. During a televised speech, Minister of Family and Social Services Derya Yanik stated, “LGBTQI+ lobbies are making their way in the world in a very systematic way. We care about fighting this structure that tries to be included in the concept of family, we find it necessary to fight.” Yanik had made similar comments in the past. Elsewhere, Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu emphasized “family values” by warning, “We’ll leave, pro-LGBT [politicians] will come in power.” And on May 1, Justice Minister Bekir Bozdağ said, “There are those who are in many efforts to legitimize and normalize the LGBT community and many perversions. It is the primary duty of states to protect every member of society against negativities, against deviant and perverted beliefs.”

Candidates promise to repatriate Syrian refugees

In the lead-up to the election, both sides made promises to voters to repatriate Syrian refugees. After the February 2023 earthquakes that killed more than 50,000 in Syria, Syrian refugees become the target of hate speech and disinformation. Today, more than three million Syrians live in Turkey, and almost all political parties pledged to send Syrians back if elected.

The ruling AKP party’s political discourse also changed toward refugees. In 2022, Erdoğan stated, “The opposition says we’ll send back Syrians if we came to power. We will not. We will continue to host.” But in a short period of time, Erdoğan’s position changed to “we’ll provide the voluntary and honorable return to our Syrian brothers.” Kılıçdaroğlu made similar a promise to voters, stating, “I will resolve the Syrian refugee issue within two years,” and pledged to send them back.

Additionally, ATA Alliance candidate and former far-right Nationalist Movement Party member Sinan Oğan said in a campaign video, “Let’s save our country from invasion of Syrians.” ATA Alliance comprises four political parties, including anti-refugee party Victory Party (ZP). In 2022, the ZP founder attempted to plant a “symbolic mine” on the border to prevent the refugees into Turkey.

During a speech on TRT, Oğan stated, “If you vote for Sinan Oğan and the ATA Alliance, 13 million refugees and migrants will leave.” Such statements fuel anti-refugee discourse in Turkish society.

Cite this case study:

Sayyara Mammadova, “A snapshot of Turkey’s information environment prior to the presidential election,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), June 7, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/06/07/a-snapshot-of-turkeys-information-environment-prior-to-the-presidential-election.