Chinese social media messaging downplays significance of Wagner mutiny

Beijing promoted the view that Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny was a one-off event and emphasized Russia’s “return to normal,” lending further legitimacy to its support for Russia and their deepening partnership

Chinese social media messaging downplays significance of Wagner mutiny

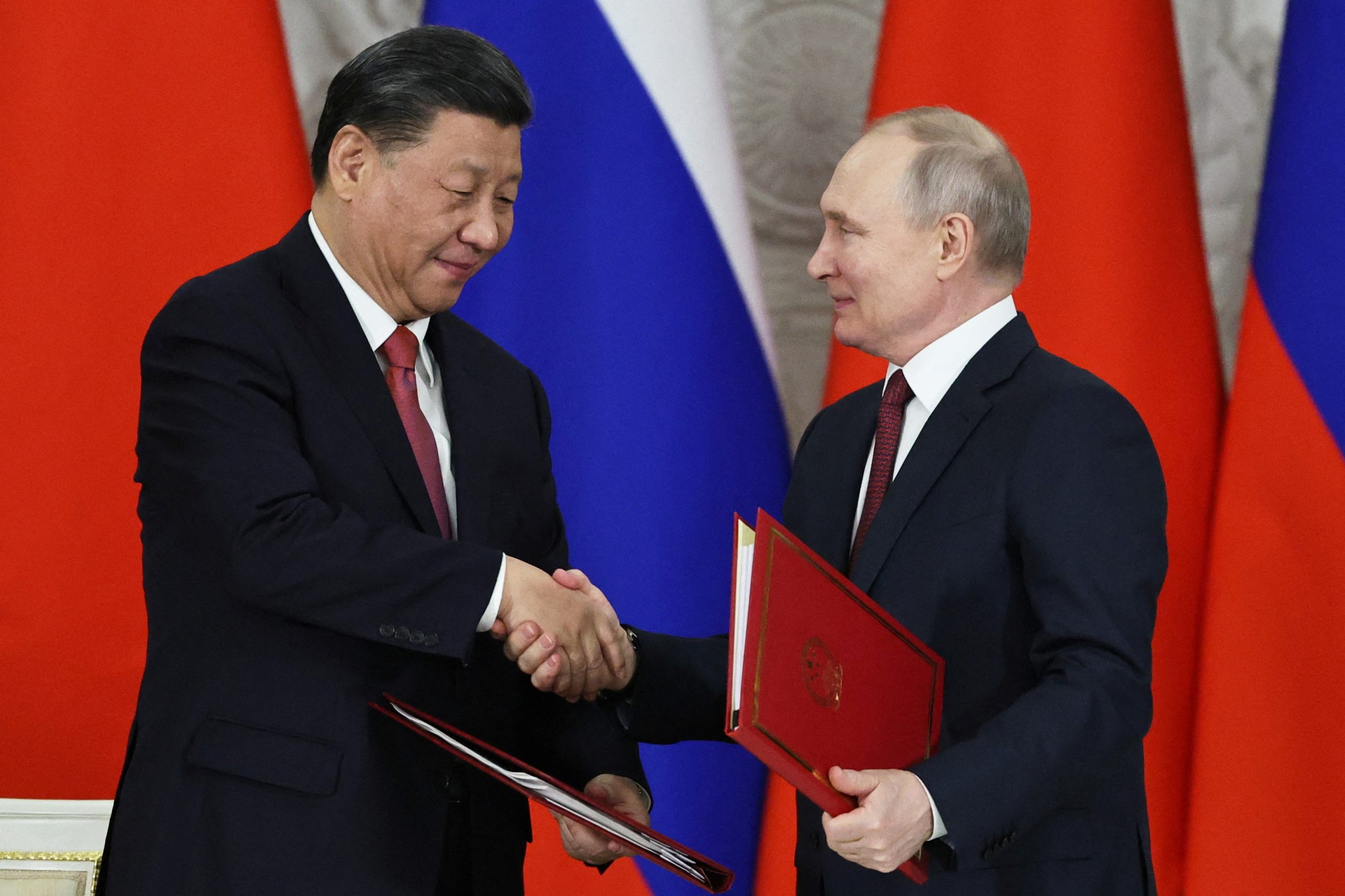

BANNER: Chinese President Xi Jinping shakes hands with Russian President Vladimir Putin during a signing ceremony following their talks at the Kremlin in Moscow, March 21, 2023. (Source: Reuters via Sputnik/Mikhail Tereshchenko/Pool)

As a shocked global audience watched a contingent of Wagner mercenaries make their way toward Moscow on June 24, 2023, official Chinese government sources remained quiet. After a cessation in hostilities the following day, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) issued a terse official statement on the matter: “This is Russia’s internal affair. As a friendly neighbor and a comprehensive strategic partner in the new era, China supports Russia in maintaining national stability and achieving development and prosperity.”

Subsequent statements from Chinese government personnel, official media organizations, government bureaus, and accounts aligned with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) issued near-identical refrains on domestic social media platforms like Weibo, as well as on global social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. The common theme in China’s messaging was to downplay the event as a singularity, seeking to portray Russia as “returned to normal” by emphasizing messages of “national stability.”

Below is a snapshot of China’s official communications on both global and domestic social media platforms in the days immediately following the mutiny.

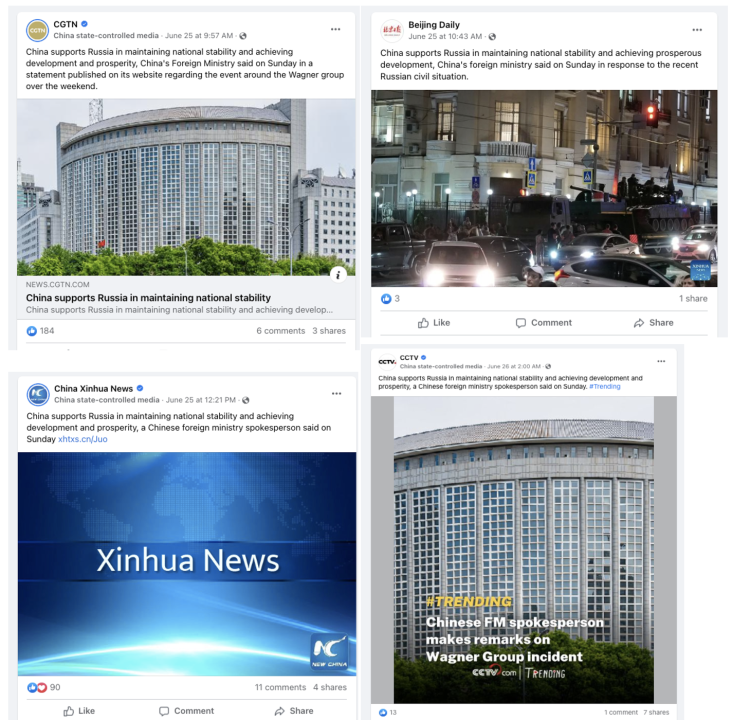

Global social media platforms

According to DFRLab analysis using the Meta-owned social media tool CrowdTangle, at least thirteen different official Chinese news organizations shared Facebook posts with language mirroring that of the MFA statement over a 24-hour period beginning on June 25. The posts had limited reach, with 912 interactions across posts during the time period, but nonetheless communicated Beijing’s official stance on the issue.

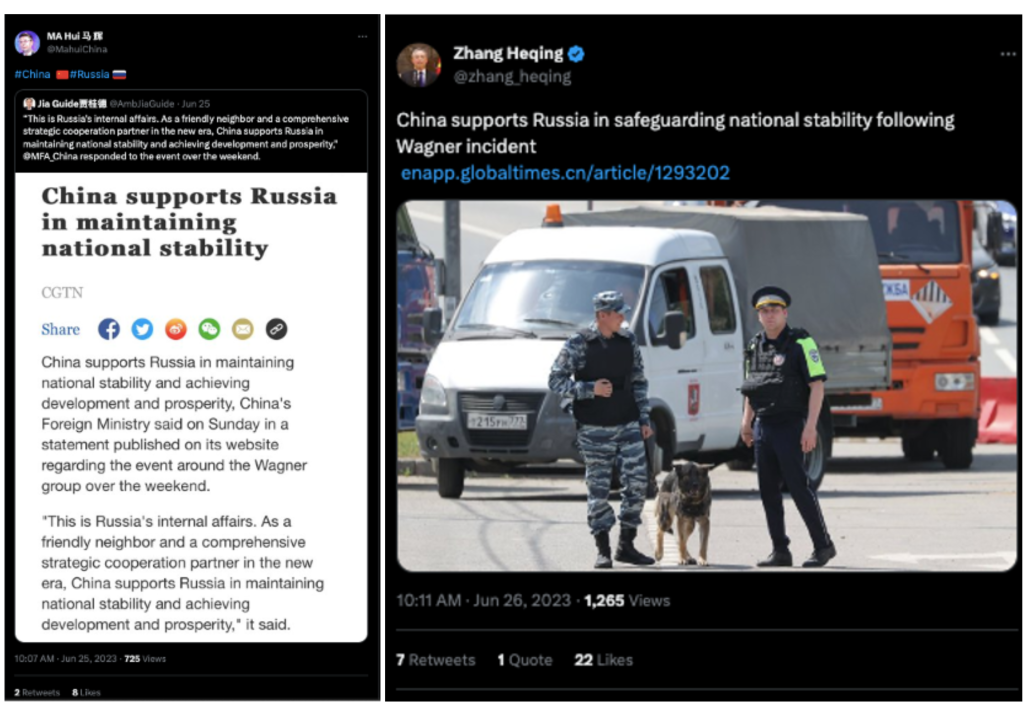

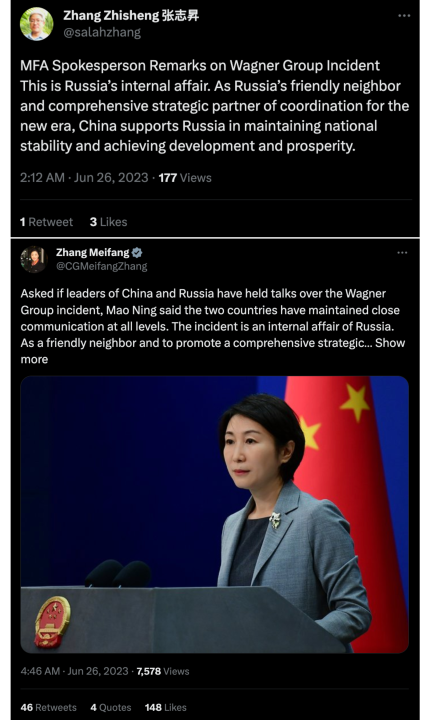

Similar patterns could be seen on Twitter. The DFRLab used the Hamilton 2.0 Dashboard to analyze over five hundred tweets from Chinese official state sources and state-linked accounts from June 24 to June 26 with the keyword “Russia.” According to the results, that the phrase “national stability” was the second most frequently used phrase within these tweets, with “Putin” appearing the most frequently.

However, state-owned media outlet Global Times – which has been linked to efforts to promote pro-Russia disinformation campaigns in the past – departed from the official line to accuse the “US-led West” of “exaggerating the aftermath of the Wagner revolt and badmouthing Putin’s authority to magnify some of the internal problems in Russia in order to weaken the country and damage the military morale of Russian soldiers.” The accusations mirror similar comments made by President Vladimir Putin in a five-minute speech the evening following the conclusion of the Wagner mutiny.

Domestic social media platforms

On domestic platforms, Chinese state entities and state-affiliated accounts amplified these narratives while censoring narratives that highlighted Russia’s internal political strife and speculated on potential outcomes. It seems that initially, the Chinese government was surprised – as was most of the world – when the mutiny first became apparent. This is evidenced by the fact that within a few hours after Putin’s speech on June 24, the hashtag “Putin Accuses Wagner Head [Prigozhin] of Treason”(#普京指责瓦格纳负责人叛国#) garnered over 1.2 billion views on Weibo and became the top trending topic on the platform that day.

Likely seeking to wrest control over the narratives, the following days saw a concerted censorship and amplification campaign to push the CCP-approved line. Domestically, the government was aiming to curb any potential negative reactions to China’s deepening and continued support of Russia in the face of clear indications that it was a potentially unstable and unreliable partner. Part of China’s toolkit for “public opinion management,” as the CCP terms it, includes using both amplification and censorship to control conversation to maintain strategic flexibility, especially on issues related to foreign affairs and politics.

On Weibo and WeChat, for example, commentary from popular accounts speculating on the aftermath of the Wagner mutiny was taken down. This includes an essay posted by former Global Times editor Hu Xijin, known for his fiery nationalistic commentary, and a post by a popular public WeChat account whose author opines on international politics through a nationalistic lens.

A similar narrative on Weibo in which Chinese netizens described Prigozhin’s mutiny as “eliminating the emperor’s cronies” (清君侧) was quickly search-censored. The phrase, originating from China’s imperial history, connotes sympathy for a loyal group seeking to usurp the power of corrupt officials in the emperor’s circle. In this instance, Prigozhin is the loyal usurper seeking to upend the corrupt power of the Russian Ministry of Defense, while Putin is the emperor. The phrase is one that is already sensitive to the CCP – it has been search-censored in the past, as it has been previously used to criticize corruption within the party.

Chinese official accounts also sought to erase any mention of the mutiny in the days following the event. A readout of a meeting between Foreign Minister Qin Gang and Russian Deputy Foreign Ministry Andrey Rudenko on June 25 made no mention of the event. Similarly, the readout of a meeting between Rudenko and Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu did not mention the Wagner mutiny, instead emphasizing China and Russia’s deepened political “mutual trust and practical cooperation” under the leadership of President Xi Jinping and President Putin. Meanwhile, the VOA reported that the Russian statement regarding the meeting highlighted China’s support for the leadership of the Russian Federation to “stabilize the situation in the country in connection with the events of June 24,” and reaffirmed its desire to “strengthen the unity and further prosperity of Russia” – seeming to indicate the mutiny was a thing of the past, and that Russia had returned to politics as normal.

Domestically, these efforts served the purpose of muting domestic public discussion of China’s continued support of a partner that is increasingly isolated internationally and unstable at home. Globally, China has also sought to present a united front with Russia against what it terms as Western efforts to undermine it, often blaming domestic unrest on the same “foreign forces” maligned by Putin and Russian government sources.

Downplaying the event serves to promote the view that the mutiny was a one-off, traitorous act by a single individual, rather than a reflection of Russia’s increasingly unraveling political fabric. In China’s view, this lends further legitimacy to its support for Russia and their deepening partnership.

Cite this case study:

Kenton Thibaut, “Chinese social media messaging downplays significance of Wagner mutiny,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), July 10, https://dfrlab.org/2023/07/10/china-reaction-to-wagner-mutiny.