Suspicious network’s copypasta replies to Sudanese paramilitary group’s tweets

Network of potentially hijacked Twitter accounts copy and pasted positive replies to accounts associated with Rapid Support Forces

Suspicious network’s copypasta replies to Sudanese paramilitary group’s tweets

Share this story

BANNER: Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, deputy head of the military council and head of paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), greets his supporters as he arrives at a meeting in Aprag village, 60 kilometers away from Khartoum, Sudan, June 22, 2019. (Source: REUTERS/Umit Bektas/File Photo)

A network of over two hundred currently active Twitter accounts copied and pasted replies to tweets by accounts associated with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the Sudanese paramilitary group currently engaged in armed conflict with the Sudanese armed forces. The accounts employed verbatim content replying to tweets by @RSFSudan, the official RSF account; @RSFLiveSD, a newly active account affiliated with the RSF; and @GeneralDagllo, the official account of RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti.

The network of 227 accounts is similar to two additional networks previously uncovered by the DFRLab. In April 2023, we uncovered a network of over nine hundred accounts used to amplify content posted by the RSF and Hemedti. Many accounts appeared to have been originally operated by real users over a decade ago before seemingly being hijacked or sold to third parties, though other indicators suggest they were established to appear real, as some malign actors establish fake accounts to appear real for a period of time, building them up over time before weaponizing them. In another investigation that same month, the DFRLab identified a network of accounts with overlapping creation dates that posted identical content. The current network appears to use a combination of tactics from both previous networks. The accounts are more than a decade old, all created on three separate days, and use posted copy-and-pasted content (“copypasta”) to promote the RSF and Hemedti.

Unlike normal copypasta campaigns, however, it attempted to make itself less obvious by spreading identical replies across multiple tweets rather than under single tweet. The network appears to have a set list of replies to use in response to the RSF, RSF Live, and Hemedti. Because of this, the network comes across as relatively authentic – scrolling through replies to a tweet by one of the three accounts, a user would not necessarily see duplicate replies from a large number of accounts in the network. However, a look at the network as a whole showed that the 227 accounts replied to tweets by Hemedti and the two RSF accounts using pre-written text.

Since fighting between the RSF and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) broke out on April 15, 2023, the two opposing forces have attempted to control the online narrative. Both RSF and SAF social media pages consistently post a deluge of information, often contradicting one another, making it nearly impossible to ascertain useful information. Changes to Twitter’s verified accounts and blue check policies have also complicated things; for example, just days after the outbreak of the fighting, a verified account impersonating the RSF claimed Hemedti had been killed.

Manipulating social media engagement using inauthentic networks is not the only tactic that has been used so far. In June 2023, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) put out a statement claiming that MSF personnel were coerced into making a propaganda video for the RSF, while fact-checking groups consistently debunk claims made by supporters of either the RSF or the SAF.

Without access to Twitter’s API, the DFRLab relied on more manual techniques to identify the network. During the investigation period, many accounts underwent changes to profile pictures, usernames and user handles in a likely attempt to appear more authentic, and some may have been overlooked for this reason.

Copypasta replies

The network appeared to primarily focus on replying to tweets by the RSF, RSF Live, and Hemedti and painted both the RSF and Hemedti in a positive light. The replies themselves were often copied. For example, on June 11 alone, eight different accounts in the network used the phrase “كل الدعم لقوات الدعم السريع” (“all support to the Rapid Support Forces”) when replying to tweets by either the RSF or RSF Live.

In other instances, the same text would be recycled, almost as if the network had a list of pre-written replies to use in response to different tweets. For example, the phrase “جاهزية سرعه حسم قوات الدعم السريع صمام امان السودان” (“Accessibility, rapidity, resolvedly, the Rapid Support Forces are Sudan’s safety valve”) was used fourteen times between May 28 and June 18 by multiple accounts in the network. “Accessibility, rapidity, resolvedly” is an RSF slogan and can be found on the group’s website. The phrase implies the RSF is Sudan’s savior.

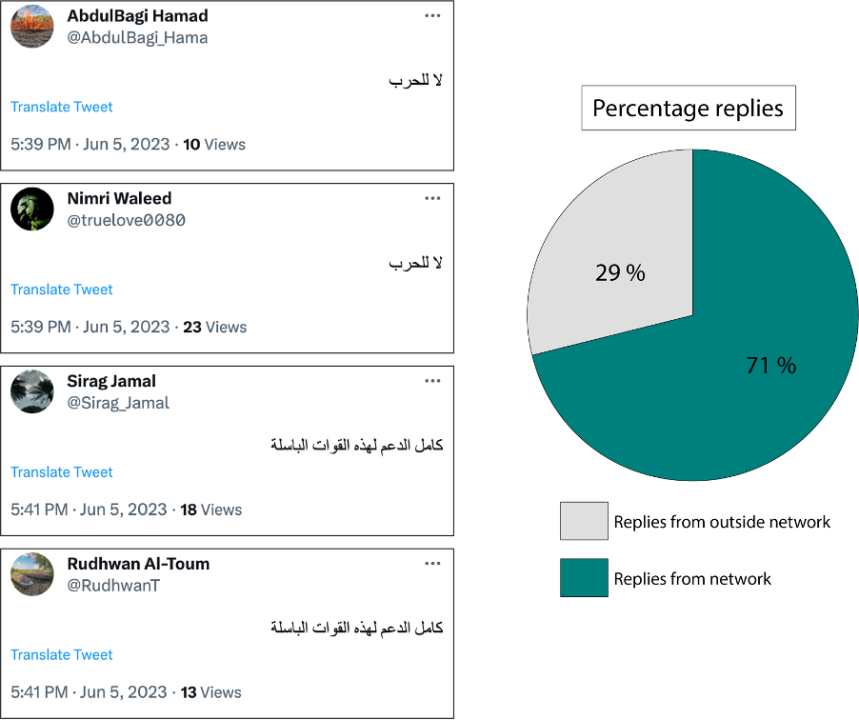

Prioritized tweets

Not every account responds to the same tweets by Hemedti, the RSF, and RSF Live accounts. However, the network appears to prioritize specific tweets, and, in some instances, replies from the network made up a significant portion of post engagement. For example, on July 5, the official RSF account posted a tweet about RSF political advisor Yusuf Ezzat meeting, Moses Wetang’ula, Kenya’s Speaker of the National Assembly. That same day, fifty-nine accounts replied to the tweet. Of those fifty-nine replies, forty-two came from accounts within the network, while only seventeen replies came from accounts seemingly not associated with the network in question.

Scanning the accounts themselves also revealed reply patterns. Groups of accounts within the network appear to reply to the same tweets, making their accounts seem very similar. Because the accounts respond to the same tweets using different text, seemingly from a list of pre-written replies, they appear relatively authentic from the outset. Taken as a whole, however, it became clear that the accounts reply to prioritized tweets using options from a pre-written list.

Repurposing old accounts

The network of over two hundred accounts displays many similar characteristics to the network of over nine hundred accounts the DFRLab previously identified, including prior usage, mismatched screen names and handles, and suspicious profile pictures. Indicators suggest that some of the accounts might have been authentic but later hijacked or sold, or perhaps initially set up to appear authentic before being deployed for inauthentic purposes.

Prior Usage

As with the previous network of potentially hijacked accounts, the accounts in this network were all created more than a decade ago. Because Twitter itself does not display account creation dates, the DFRLab used monitoring tool TruthNest to ascertain that every account in the network was created on one of three days in 2012: July 18, July 19, or September 16.

A select few accounts also showed evidence of having lived past lives. At least forty-eight accounts retained their tweets from many years ago, some in different languages such as Korean, Indonesian, Spanish, English, and Tagalog. Posts topics varied considerably; some posted their support for musicians while others posted about video games or how, in 2012, they did not know how to use Twitter. Many included personal images and links to Instagram accounts. All of these factors would normally be considered indicators of authenticity, though the overlapping creation dates suggests the opposite, raising questions about their legitimacy. Notably, prior to late May 2023, none of the accounts had posted about Sudan, the RSF, or Hemedti.

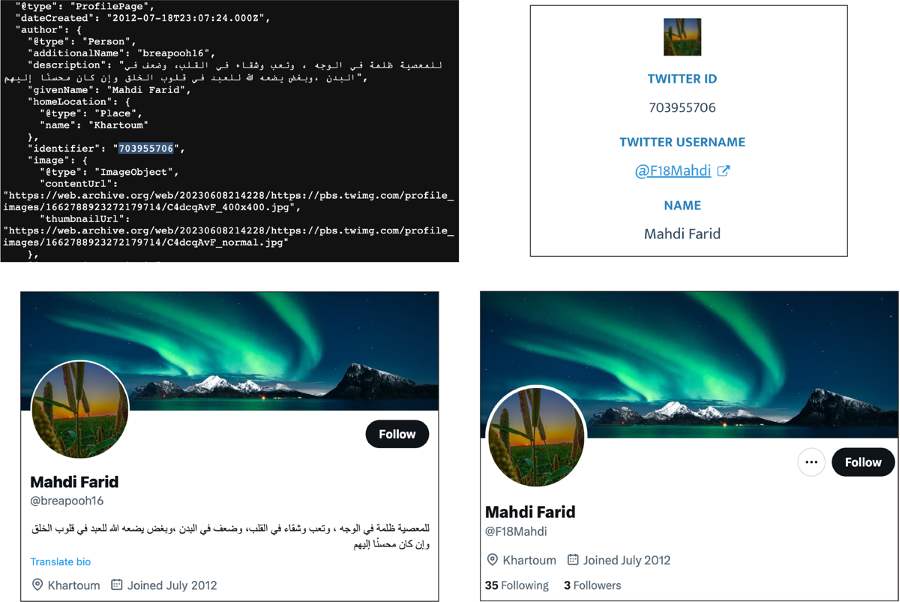

Mismatched user handles and usernames

Evidence that some of the accounts had been repurposed to promote the RSF came in the form of mismatched user handles and usernames. Usernames are easy to change and do not need to be unique, modifying a user handle requires intentionally selecting one that is unique to the platform.

At time of publishing, some accounts in the network had changed their username but not their user handle, resulting in a combination of Arabic usernames and non-Arabic user handles, as well as usernames typically associated with men alongside user handles typically associated with women.

During the period of investigation, the DFRLab noticed that multiple accounts in the network altered their user handles to align with their usernames, likely to make the accounts appear as if they were not hijacked. For example, the DFRLab archived an account with the user handle @breapooh16 on June 8, 2023. The archived account’s Twitter ID, which is unique to every account and cannot be changed, was visible when looking at the archived page’s source code. @breapooh16’s user ID was 703955706. Using a third-party tool, Comment Picker, the DFRLab was able to confirm that the same user ID now corresponds to an account with the user handle @F18Mahdi, showing that @breapooh16 changed its user handle to @F18Mahdi sometime after the DFRLab archived it on June 8.

Generic profile pictures

Furthermore, some accounts in the network pilfered publicly available photos for their profile photos. A few accounts stole pictures of real people from Facebook and Instagram pages posting pictures of Sudanese people. For example, the account @AminYas06433590 stole a picture for its avatar from an Instagram page called zamaaan, while @EhsanMu85155699 used a picture from another page called Karkab Travel.

In another suspicious example, the accounts @nasir__nabeel and @Matthew_abiodu used the same profile picture; this tactic appears to have been used infrequently, however.

Original tweets

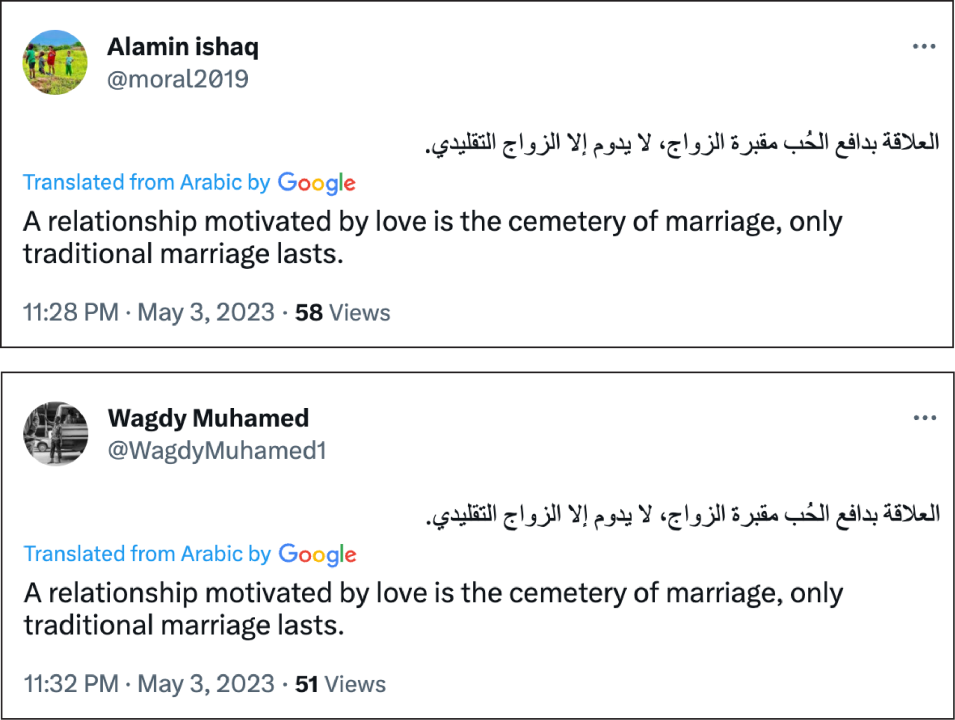

While some accounts were used solely to reply to RSF-related tweets, others posted original text on occasion. These original tweets were exclusively in Arabic, potentially in an attempt to appear more authentic. The tweets themselves appeared to primarily be quotes from the Quran or inspirational quotes. A similar tactic was identified in the previous network of nine hundred accounts.

Some original tweets were copied from other Twitter accounts. For example, the user @Qasim_Jubair copied the text and image from a tweet originally posted by a popular Twitter news account and posted it as an original tweet.

The DFRLab also found evidence of accounts in the network tweeting identical content. On May 3, the accounts @moral2019 and @WagdyMuhamed1 both tweeted the same text of a quote four minutes apart. The quote was posted on Twitter a day earlier by a popular entertainment account.

Breaking the pattern

Of the 227 accounts the DFRLab identified, only eighty followed either the RSF, RSF Live, or Hemedti’s account, despite replying to and sometimes even liking and retweeting content from the three accounts. The DFRLab noted that the majority of accounts followed an account that, at time of publishing, went by the user handle @Alnmoor23. In fact, only forty-nine of 227 total accounts were not following @Alnmoor23.

When the DFRLab first started investigating the network, the @Alnmoor23 account looked quite different. Originally, the account used @Malik23Ibrahim as its user handle, and “Malik Ibrahim” as its username. An investigation of @Alnmoor23 using the third-party application Comment Picker showed the account’s user ID was the same as the archived version of @Malik23Ibrahim.

Before changing to @Alnmoor23, the @Malik23Ibrahim account acted similarly to other accounts in the network, including replying to tweets by the RSF, RSF Live, and Hemedti with copied content. On May 28, it and eight other accounts in the network responded to a post by Hemedti using identical text.

Unlike other accounts, @Alnmoor23 replied to accounts that were not the RSF, RSFLive, or Hemedti. While other accounts in the network occasionally post generic quotes or passages from the Quran, the Alnmoor23 account creates original content promoting the RSF. Ultimately, the DFRLab could not ascertain the purpose of the @Alnmoor23 account and why it broke the pattern the other 226 accounts in the network.

Evidence of a potential inauthentic network of Twitter accounts amplifying the RSF continues to emerge, suggesting coordinated efforts to enhance the image of the paramilitary group both before and after the current conflict broke out. Despite suspensions of prior networks, it appears that these newly discovered accounts serve the same objective. The weaponization of social media accounts is particularly important in the context of the ongoing online conflict between the RSF and SAF, as both sides attempt to win the narrative battle.

Cite this case study:

Tessa Knight, “Suspicious network’s copypasta replies to Sudanese paramilitary group’s tweets,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), August 2, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/08/02/suspicious-networks-copypasta-replies-to-sudanese-paramilitary-groups-tweets/.