Panda exchange program targeted by misinformation, driving anti-US narratives in China

Chinese media capitalized on emotionally resonant rumors about alleged panda abuse in the United States amid deteriorating US-China relations

Panda exchange program targeted by misinformation, driving anti-US narratives in China

Share this story

BANNER: Screencaps of a viral Douyin video of animated panda flight attendants welcoming Ya Ya’s arrival with the song, “Ya Ya Come Home.” (Source: 四川西南航空职业学院/archive)

DISCLAIMER: This report contains images of pandas experiencing natural health challenges that might cause some distress in viewers.

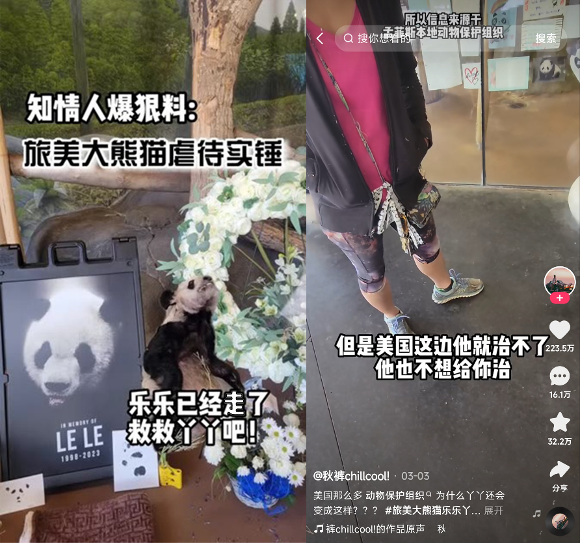

Influenced by rumors and misinformation, Chinese social media users – and some animal rights activists in the West – targeted the Memphis Zoo for the alleged mistreatment of its pandas, while Chinese state media also joined in the campaign. Independent Chinese media further amplified the misinformation to generate traffic for profit using messaging techniques that garnered anger and sympathy. Both the Memphis Zoo and its Chinese counterpart publicly refuted the allegations, but that did little to sway the online vitriol.

China uses panda diplomacy – a goodwill endeavor entailing lending pandas to foreign zoos – to showcase its environmental protection efforts. These panda exchanges are designed to symbolize China abroad through the embodiment of cute and cuddly animals, shaping a “peaceful and friendly” perception of the country and a positive bilateral relationship with countries involved in the exchange program. The most famous instance of panda diplomacy occurred after then-US President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972, when the United States received two pandas from China as part of the easing of US-China tensions during the Cold War. More than fifty years later, amid increased competition between the US and China, the deterioration of US-China relations is now echoed in Chinese narratives alleging the Memphis Zoo mistreated two pandas, Le Le and Ya Ya. The narratives are deeply rooted in Chinese nationalism and mistrust of the West and have been amplified across Chinese media and social media.

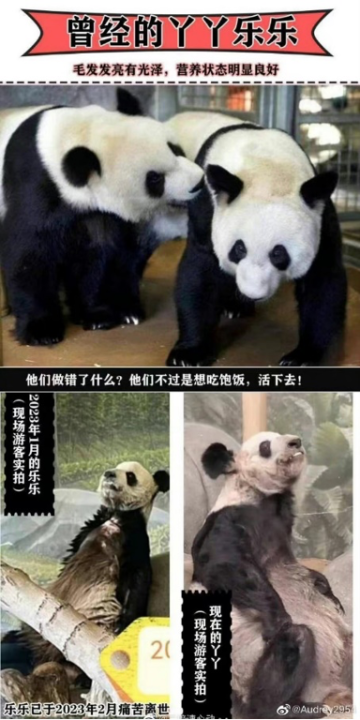

The two pandas called the Memphis Zoo home from 2003 to 2023. According to the zoo’s contract with the Chinese government, they were both set to return to China in April 2023. On February 1, however, Le Le passed away suddenly at age 24, drawing attention to Le Le’s partner, 22-year-old Ya Ya. Their pictures circulated on social media, seemingly showing the pandas as frail and disheveled. According to a February 2023 statement by the Memphis Zoo, Ya Ya’s appearance was the result of “a chronic skin and fur condition, which is inherently related to her immune system and directly impacted by hormonal fluctuations,” adding, “This condition does not affect her quality of life but does occasionally make her hair look thin and patchy.”

Fueled by nationalist anger, Chinese social media users scrutinized the practices of the Memphis Zoo, which they deemed responsible for Le Le’s death and Ya Ya’s frail appearance. Misinformation ran rampant, including unsupported rumors that zookeepers abused Le Le, stabbed him, and sold his eyeball; that the zoo cramped the pandas inside dirty living conditions without social interactions; and that the pandas had been kowtowing to beg for food, only to be tossed yellowing, old, and dry bamboo that did not meet Chinese standards. The overarching theme of these narratives was that the Memphis Zoo had supposedly tormented a defenseless icon of the Chinese nation.

Following the February 2023 statement, the Memphis Zoo and its Chinese counterpart, the Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens, released joint statements noting they were well aware of the pandas’ chronic health conditions and had exchanged monthly health reports since their arrival at the facility. Despite these statements, the concerns of Ya Ya’s fans persisted and even received mainstream media attention in the West.

The DFRLab reached out to the Memphis Zoo for comment. “In the months leading up to Ya Ya’s departure, the Memphis Zoo experienced a substantial surge in viewership on its online Giant panda cameras,” a spokesperson replied. “The increase was so significant that Memphis Zoo found it necessary to increase its streaming hours during the first weeks of the month.” In addition, social media posts indicated that some people traveled great distances across the US to “protect” Ya Ya.

A public distraction?

To visualize the growth of the narratives, the DFRLab gathered engagement metrics from multiple Chinese internet platforms, including Baidu, a search engine; Douyin, the China-focused precursor to TikTok; WeChat, a messaging platform; and Weibo, a microblogging platform akin to Twitter. Although Le Le died on February 1, his death did not trigger a noticeable increase of interest in Ya Ya in China on most platforms, the data suggests. During that time, concern for the pandas appears to be mostly from two Western animal rights organizations, In Defense of Animals and Panda Voices, which had lobbied for the pandas’ release. Since 2021, Panda Voices has been one of the most influential organizations to put forth the “begging for food” narrative, which contradicts the Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens’ belief that the pandas were “receiving the highest quality of care.” It was not until three weeks later on February 22, that Ya Ya narratives suddenly began to strike a chord in China.

One potential explanation for this spike in interest was that the Ya Ya narratives served to crowd out the information environment on the same day as a deadly mine collapse in Inner Mongolia. According to the Weibo Hot Search Search Engine, the hashtag Ya Ya (“丫丫”) appeared its leaderboards for a total of 1,047 minutes, whereas the hashtag “2 Dead, 6 Injured, 53 Lost in Inner Mongolia Coal Mine Collapse” (“内蒙古煤矿坍塌已致2死6伤53失联”) appeared for 225 minutes. Major state media on Weibo have not given an update on the collapse since February 25. Coverage of public safety incidents on social media has been stymied in the past through government censorship and flooding the information environment with distracting narratives. Chinese President Xi Jinping has required social media companies to prevent the spread of negative information and to support “positive energies” (“正能量”), a euphemism for news that inspires positive, uplifting emotions, and good perceptions of Chinese governance and the Chinese Communist Party.

Although the mine collapse quickly faded from public discourse, the DFRLab does not have sufficient evidence to conclude that posts about Ya Ya on Weibo were artificially amplified in response to the disaster. The collapse occurred around 1:00 PM China Standard Time on February 22; by then, Ya Ya-related hashtags were rising on the hot search leaderboards, a trend which began the previous day. A likely explanation is that Xiang Xiang, a panda that was on lease to Japan, returned to China on February 21, which then shifted discussion to Ya Ya. Since then, interest in Ya Ya has remained elevated, as have rumors and misinformation about her condition.

Capitalizing on Ya Ya the panda brand

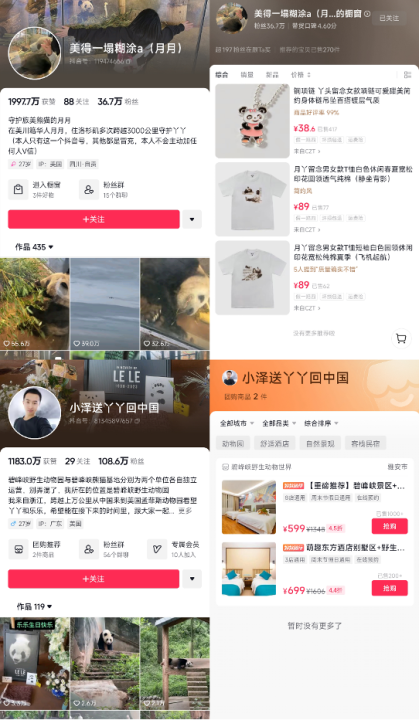

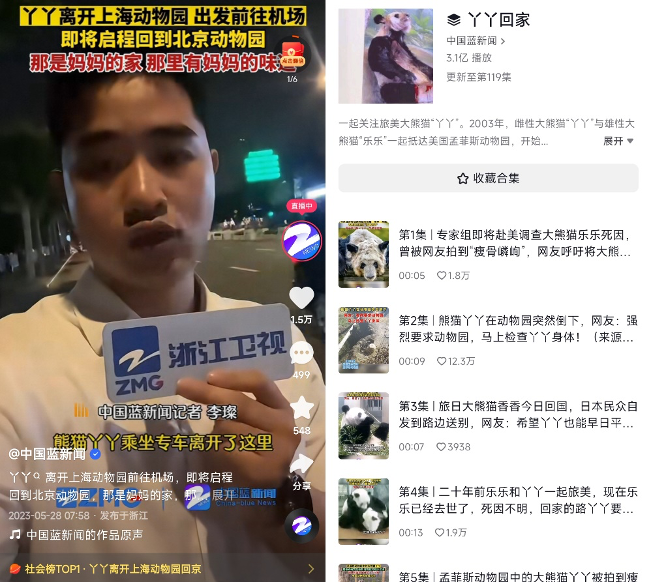

After Ya Ya content began driving page views on February 22, some Douyin users produced emotionally charged content, gaining exposure and followers. For instance, Yue Yue, a Chinese national residing in Los Angeles, took particular interest in “guarding” Ya Ya as a form of nationalistic expression; she took time off from work and flew to Memphis on four occasions, totaling over thirty days, to film Ya Ya and monitor her condition. In one viral video, the blogger called to the panda in a Sichuanese dialect of Mandarin. The panda moved shortly thereafter, though it was unlikely in response to the blogger’s call, but that did not stop observers from inferring that the panda understands Chinese and “misses home.” (Alongside the provinces of Shaanxi and Ganzu, Sichuan Province is one of three provinces home to most of the remaining wild pandas.) Yue Yue’s Douyin account eventually went from near-zero engagement to over 19.9 million total likes. As one of the most prominent of Ya Ya’s self-proclaimed advocates, she was subsequently interviewed by state media.

Another Douyin video blogger who camped outside Ya Ya’s enclosure, Little Ze, achieved similar success as Yue Yue, garnering 11.8 million total likes and one million followers. Both Yue Yue and Little Ze have started storefronts on Douyin to sell apparel and vacation packages, respectively. Yue Yue has sold 270 items from her store; estimating from the least expensive item, the DFRLab estimates that she has generated at least 10,422 RMB (~$1,460) in revenue.

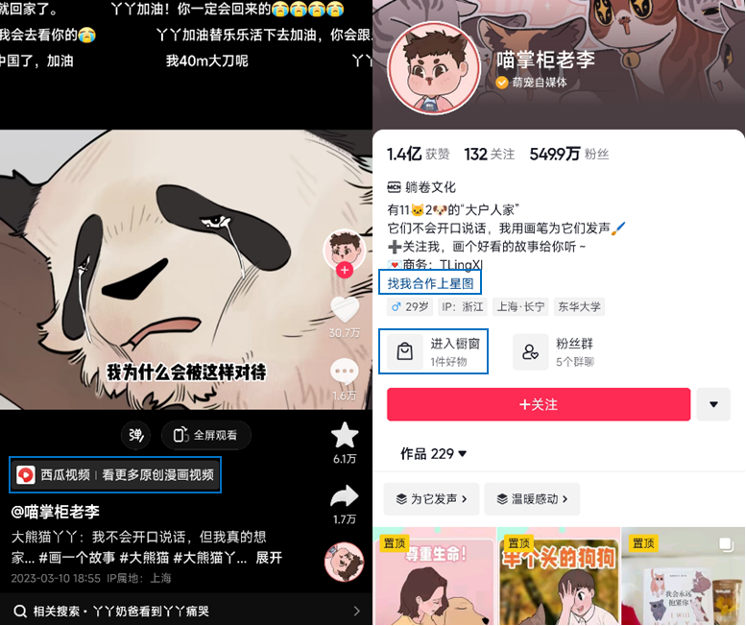

In another popular post, one user animated a video of Ya Ya, narrating the panda’s supposed inner thoughts to elicit sympathy. In the video, cartoon Ya Ya exclaims, “I’m Ya Ya… I’m sitting in a dirty, smelly house… I’m so homesick… I’m often so hungry that I’m about to pass out.” As is the case with other Ya Ya influencers, the publisher of the animation benefits financially through monetization of content and through sales of related merchandise sold via the built-in Douyin storefront.

A content creator on Kuaishou, another Chinese short video platform, filmed a skit of a person in a Ya Ya costume being tormented by another person wearing an eagle mask, but is saved and fed by a vigilante. This skit of Ya Ya contains many of the established misinformation narratives – it features a montage of the various accusations – and its creator also profits from ad revenue and merchandising sales.

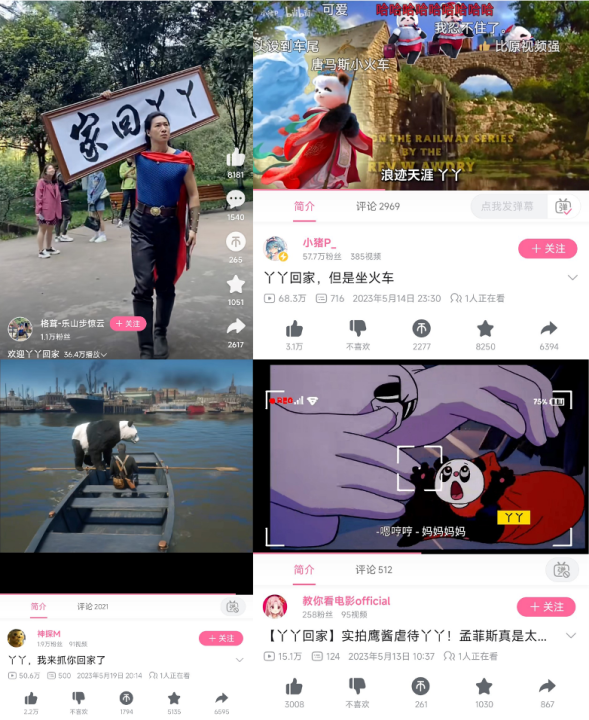

The concern for Ya Ya attracted commercial interests looking to promote their brands on Ya Ya’s coattails. The promotional potential of Ya Ya led to an unofficial anthem, for example; a singer on Douyin produced an original song called “Ya Ya Come Home” (“丫丫回家吧”). Other users borrowed its catchy chorus as background music for their Ya Ya-related content, including a video — which itself became a meme — jointly produced by a college and a cartoon company.

A battle of panda pics

The sustained media attention persisted for over a month and culminated in Ya Ya’s return to China on April 27, 2023. Activists congratulated themselves for bringing her home, even though they had no obvious impact to her travel schedule. The terms of the Memphis Zoo’s agreement with China required the pandas’ repatriation in 2023, so any claims of success did not account for this inevitability.

The most liked and shared Weibo posts on the day of Ya Ya’s repatriation came from state media celebrating her return.

Since unflattering images of Ya Ya triggered the repatriation movement, photographs have continued to play an important role in the spread of narratives. In a May 24 Douyin post, a user claimed that Ya Ya had gained twenty-six pounds after over twenty days of rehabilitation at the Shanghai Zoo. In the photo gallery, the first four pictures are portraits of a panda, implying that they are of Ya Ya. However, the overly posed images appear to be AI-generated. For example, similar AI-generated portraits of pandas are available on clip art sites. The DFRLab cannot confirm that this post was the originator of the weight gain claim, but the narrative later spread to other platforms.

In addition to Ya Ya’s alleged weight gain, an account on Douyin with fewer than two hundred followers posted a video claiming that Ya Ya’s skin condition had also gotten “80 percent better.” In the video, the narrator can also be heard saying, “Very good and beautiful, now baby Ya Ya is white and fat,” but the footage underneath that statement was actually taken at the Memphis Zoo. This video might have otherwise gone unnoticed, but a verified government propaganda account, Qilihe Announcements, amplified it on Weibo, receiving over 30,000 likes.

These narratives continued on May 28, when authorities released the latest photos of Ya Ya after her transfer from Shanghai to Beijing. Chinese media sought to compare Ya Ya’s current condition to her time in Memphis. Two Weibo hashtags moderated by China Central Television, “Ya Ya is visibly fatter” (“丫丫肉眼可见地胖了”) and “As soon as Ya Ya got home, she was surrounded by bamboo” (“丫丫一到家就被竹子包围了”) both played up the supposed contrast between her more recent appearance and her alleged “poor diet” in the United States. Weibo allows approved accounts, or “topic moderators,” to manage posts that reuse the hashtags on the approved account’s dedicated page, such as pinning, recommending, or blocking posts from other accounts.

The visual contrast, however, appeared to be more of a matter of staging and locale: Ya Ya sported groomed hair in a decorated, brightly lit room, which seemed to have convinced Chinese internet users that a real change in her health had occurred and that their hard work speaking out for Ya Ya had paid off, a “smack in the face” to those who had previously noted Ya Ya’s age and skin disorder.

With Ya Ya safely back in China, supporters turned their rescue efforts to other pandas, particularly those currently at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park in Washington, DC. Its three pandas, Tian Tian, Mei Xiang, and Xiao Qi Ji, are scheduled to return to China before the zoo’s contract with the China Wildlife Conservation Association expires on December 7, 2023. In May 2023, an image purporting to show Tian Tian sedated and restrained during an examination circulated on Weibo, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu. The photo, however, actually depicts a panda in China’s Fujian Province undergoing an examination in 2005; at the time, Tian Tian had been living at the National Zoo for five years.

Emotional resonance drives traffic

The narratives surrounding the pandas touched the hearts of many Chinese internet users because they provoked emotionally resonant and nationalist sentiment, fed by misinformation and populist activism. In research conducted on Chinese online discourse, Guobin Yang, a Professor of Communication and Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, found that emotions that inspire collective action the most are anger, sympathy, and humor. Separately, Guo Xiaoan, a research fellow of Chongqing University, noted, “The logic followed by China’s social protests is not of rational calculation, but emotional mobilization,” adding that “internet rumors are the common and most effective means of emotional mobilization.”

In the case of the Memphis Zoo pandas, false allegations of mistreatment provoked anger, while memes attempting to generate sympathy or even anthropomorphize them successfully resonated with millions of internet users. These narratives also fabricated an implicit struggle between the powerless and the powerful: the pandas (i.e., the powerless) were the supposed victims of the Memphis Zoo, which is run by ostensibly hegemonic Americans (i.e., the powerful) out to sabotage China. Constructing a façade of power imbalance to intensify emotional response and mobilization is often seen in populist protests within China.

In an article titled in Mandarin, “Propaganda Needs to Manage Traffic Well,” the Zhejiang Propaganda Department applied the theories of “emotional mobilization” to its propaganda work and stressed the necessity for state media to wield traffic, writing:

Traffic should flow from the fingertips to the heart. To manage traffic, you cannot just let the audience tap on their mobile phones, but also let their hearts move. If our communication and audience do not “electrify,” we will lose our voice in the massive flow of information. If the central voice does not have traffic, the “mainstream” will become a “tributary stream” or even an “endstream.”

Chinese state media also found success in engaging its audiences with Ya Ya content via an emerging form of entertainment known as “slow live streams” (“慢直播”). Unlike regular live streams, slow live streams capture a peaceful, continuous process observed by fixed cameras accompanied by natural sounds or tranquil music. Chinese state media repurposed the Memphis Zoo’s existing panda cams create their own versions of the live streams. Viewers turned to their streams for everyday escapism, as well as shared participation in monitoring the well-being of Ya Ya and her treatment by ostensibly “abusive” zookeepers. Fan communities developed in Chinese chatrooms, which helped Zhejiang Television’s 268-hour Ya Ya slow live stream to accumulate over one million comments.

After inducing interest in “saving” Ya Ya, Zhejiang Television published an academic article in the official journal of the National Radio and Television Administration. Titled “From a Few Comments from Netizens to an S-Level Broadcasting Hit With 3 Billion Traffic: Taking China Blue News ‘Panda Ya Ya’ Converging Media Coverage as an Example,” the article reads like an analytics presentation to network executives, detailing its engagement metrics and taking credit for the discovery and the success of the narrative. According to the article, Zhejiang Television combined the advantages of different social platforms with “emotional mobilization” to maximize traffic, including using livestreams to introduce Ya Ya and serialized short videos to keep her name trending, emphasizing empathy and audience interaction to enhance engagement, and synchronizing cross-platform messaging for maximum reach.

Anti-humor

State and independent media that have reaped traffic from Ya Ya-related content have little incentive to dispel misinformation about her alleged treatment. To publicly acknowledge that Ya Ya was not mistreated would turn the prevailing narrative of the national treasure’s daring “escape” from her “American oppressors” to a mundane transfer of retirement homes. Even worse, those who dispelled such narratives might be accused of whitewashing on behalf of the United States, leading to harassment from fans who swore to protect Ya Ya. Despite facing “unprecedented online harassment” from Ya Ya’s supporters, animal blogger “Crawl the World” (“爬行天下”) was one of the most vocal in dispelling the rumors, opposing the continuous sensationalism by Chinese media in a video entitled, “Has Ya Ya, the panda living in the United States, been abused? Officials Repeatedly Refute Rumors and No One Listens?”

While the Chinese information environment has been largely saturated with concern for Ya Ya, users on Chinese video platform Bilibili who rejected the false narratives produced parody videos and left sarcastic comments. Dissenting voices used humor to enliven their messaging and ridicule the mainstream movement. Sarcasm obfuscates political positions, providing political deniability when “wrong” opinions face party discipline. The DFRLab observed that Bilibili’s recommendation algorithm seems to know which videos of Ya Ya are parodies and recommends them to skeptics, informally connecting them to form a community against the mainstream – or perhaps redirecting them to talk among themselves.

As speculation over a looming East-West conflict over Taiwan continues to make headlines, environmental and conservational cooperation is often seen as a path to re-establish dialogue and rebuild trust. Five decades of panda exchanges between China in the US have led to greater cooperation among zoologists and environmentalists, increased national pride over one of China’s most beloved national symbols, and several generations of enthusiastic panda fans in the US. Yet recent misinformation and disinformation around the pandas participating in the exchange program also bred further mistrust among Chinese internet users about the United States, potentially closing another avenue of cooperation. One Weibo user captured this sentiment: “We will never send our national treasures to the United States again, and let the Americans abuse them!”

Cite this case study:

“Panda exchange program targeted by misinformation, driving anti-US narratives in China,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), September 14, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/09/14/cute-and-cuddly-pandas-drive-anti-american-misinformation.