This Job Post Will Get You Kidnapped: A Deadly Cycle of Crime, Cyberscams, and Civil War in Myanmar

In Myanmar, cybercrime has become an effective vehicle through which nonstate actors can fund and perpetuate conflict.

This Job Post Will Get You Kidnapped: A Deadly Cycle of Crime, Cyberscams, and Civil War in Myanmar

Table of contents

Executive Summary

Following decades of cyclical insecurity in Myanmar, conflict reached a new level following a coup d’etat in 2021 during which Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, deposed the democratically elected National League for Democracy government.1Richard C. Paddock, “Myanmar’s Coup and Its Aftermath, Explained,” The New York Times, December 9, 2022, , https://www.nytimes.com/article/myanmar-news-protests-coup.html. Meanwhile, criminal syndicates, entrenched primarily in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) like Shwe Kokko within Myanmar’s Karen state,2Alternatively, Kayin state have expanded and evolved their criminal operations throughout this evolving conflict. The Tatmadaw forces have intertwined themselves in complicated and carefully balanced alliances to support the ongoing conflict, including with the Karen State Border Guard Force (BGF) . As the Tatmadaw and BGF look to sustain themselves and outlast each other, they have found allies of convenience and alternative funding sources in the criminal groups operating in Karen state.3“Crowdfunding a War: The Money behind Myanmar’s Resistance,” International Crisis Group, December 20, 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/328-crowdfunding-war-money-behind-myanmars-resistance; Priscilla A. Clapp and Jason Tower, Myanmar’s Criminal Zones: A Growing Threat to Global Security, The United States Institute of Peace, November 9, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/11/myanmars-criminal-zones-growing-threat-global-security. In the last two years, organized criminal groups in Myanmar have expanded their activities to include forms of profitable cybercrime and increased their partnership with the BGF, which enables their operations in return for a cut of the illicit profits. Since roughly 2020, criminal syndicates across Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand have largely lured individuals with fake offers of employment at resorts or casinos operating as criminal fronts where they are detained, beaten, and forced to scam, steal from, and defraud people over the internet.4“The Gangs That Kidnap Asians and Force Them to Commit Cyberfraud,” The Economist, October 6, 2022, https://www.economist.com/asia/2022/10/06/the-gangs-that-kidnap-asians-and-force-them-to-commit-cyberfraud. The tactics—kidnap-to-scam operations—evolved in response to the pandemic and to the Myanmar civil war, allowing criminal groups to build on existing networks and capabilities. These operations do not require significant upfront investment or technical expertise, but what they do need is time—time that can be stolen from victims trapped in the region’s already developed human trafficking network. The profits that these syndicates reap from victims around the globe add fuel to the ongoing civil war in Myanmar and threaten the stability of Southeast Asia. These groups entrench themselves and their illicit activities into the local environment by bribing, partnering with, or otherwise paying off a key local faction within the Myanmar civil war,5Naw Betty Han, “The Business of the Kayin State Border Guard Force,” Frontier Myanmar, December 16, 2019, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-business-of-the-kayin-state-border-guard-force/. creating an interconnectedness between regional instability and profit-generating cybercrime.

What is unfolding in Myanmar challenges conventional interpretations of cybercrime and the tacit separation of criminal activities in cyberspace from armed conflict. The criminal syndicates, and their BGF partners, adapted to the instability in Myanmar so effectively that each is financially and even existentially motivated to perpetuate this instability.

This paper explores the connectivity between cybercriminal activities and violence, instability, and armed conflict in a vulnerable region, exploring how cybercrime has become an effective vehicle through which nonstate actors can fund and perpetuate conflict. The following section examines the key precipitating conditions of this case, traces the use of cyberscams to create significant financial losses for victims across the world, sow instability across Southeast Asia, exacerbate the violence in Myanmar, and, finally, considers the risks that this model could be adopted and evolved elsewhere. This paper concludes with implications for the policy and research communities, highlighting the ways in which conflict can move, unbounded, between the cyber and physical domains as combatants and opportunists alike follow clear incentives to marry strategic and financial gain.

Introduction

Cybercrime and cyber fraud, from ransomware to financial data fraud and romance scams, have reached a new high in Southeast Asia, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), driven in part by “the increasing number of available targets and the perception of cybercrime as highly profitable with a relatively low risk of detection.”6“Cybercrime and COVID19 in Southeast Asia: An Evolving Picture,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, May 16, 2021, https://www.unodc.org/documents/Advocacy-Section/UNODC_CYBERCRIME_AND_COVID19_in_Southeast_Asia_-_April_2021_-_UNCLASSIFIED_FINAL_V2.1_16-05-2021_DISSEMINATED.pdf. Cybercrime is a growing business worldwide; the relative accessibility of cybercrime tools combined with increasing reliance on online banking and the immense geographic reach that the domain provides to create a wealth of opportunity for those eager to exploit others for profit.7“Cybercrime,” accessed October 13, 2023, https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Cybercrime; E. Rutger Leukfeldt, Anita Lavorgna, and Edward R. Kleemans, “Organised Cybercrime or Cybercrime That Is Organised? An Assessment of the Conceptualisation of Financial Cybercrime as Organised Crime,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 23 (2017), 287–300, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10610-016-9332-z.

Criminal groups increasingly occupy a space between traditional crime and cybercrime, engaging in a multitude of interrelated and cross-supportive criminal activities. For more than a decade, organized criminal groups have moved into new online criminal markets while also engaging in cybercrime “to facilitate offline organized crime activities.”8“UNODC Teaching Module Series: Criminal Groups Engaging in Cyber Organized Crime,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, accessed October 13, 2023, https://www.unodc.org/e4j/zh/cybercrime/module-13/key-issues/criminal-groups-engaging-in-cyber-organized-crime.html

In Myanmar, the pursuit of cybercrime profits not only facilitates traditional crime, but also directly supports the armed organizations waging civil war across the state. Myanmar criminal groups and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) are engaged in a symbiotic relationship: criminal operations have flourished in the permissive environment of post-coup, war-torn Myanmar. Within Karen state, these criminal syndicates have in turn provided the Karen State Border Guard Force (BGF)—a key EAO in the conflict aligned with the Tatmadaw—with a desperately needed source of funding for their ongoing war.

A Cycle of Crime and Conflict

Cybercrime and its symbiotic relationship to the Myanmar civil war emerged and evolved within the context of several internal and external shocks. The 2020 outbreak of COVID-19 had a devastating effect on tourism in Southeast Asia, limiting the supply of ready targets for fraud and myriad extortion schemes. Myanmar’s February 2021 coup destabilized a nascent regime and returned the country to a state of sustained conflict.

However, these shocks only served to amplify existing tensions in Myanmar including a deeply fractured governance landscape, a history of corruption across the country, and established regional organized criminal networks. Criminal groups in a chaotic and unstable environment with little to no rule of law sought out a limited, profitable resource—trafficked individuals from across the region—and forced them to engage in cyber fraud. Armed groups seeking to assert power and dominance within Myanmar with little legitimate means of generating income or war materiel sought to establish a symbiotic relationship with criminal groups that could provide a steady source of profit.

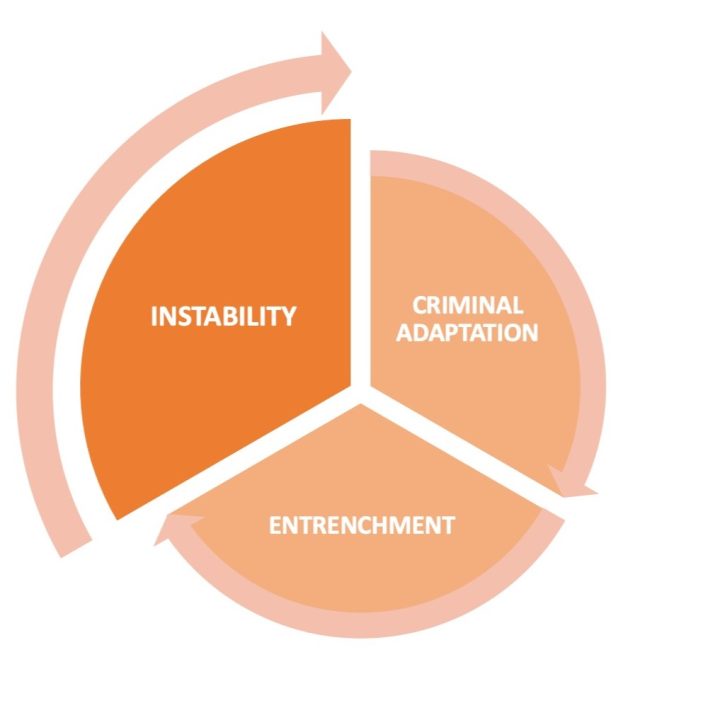

These catalysts and precipitating conditions lay the foundation for the model of cybercrime-funded conflict seen in Myanmar. However, it is the cyclical patterns of instability, criminal adaptation, and corrupt entrenchment that have created a self-reinforcing cycle of criminality and conflict—a cycle that may create an exportable model of cybercrime-funded conflict in new regions around the world.

INSTABILTY: The first portion of this cycle analyzes the conflict and instability within Myanmar both before and after the coup in February 2021. This section first provides the background to the insecurity in the country, especially surrounding the February 2021 coup that overthrew Myanmar’s democratically elected government. It lays out the fractured governance landscape of modern-day Myanmar and gives an overview of the key players in the conflict. This section then addresses the financial position of the combatants, and their emerging need to seek alternative funding sources, serving as a transition through which to better understand the relationship of armed conflict and the illicit economy in Myanmar.

CRIMINAL ADAPTATION: This section dives into cybercriminal activity in Karen state’s Shwe Kokko economic zone, examining the emergence of a massive kidnap-to-scam operation. This section examines how, in the context of the previously discussed fractured governance landscape and established criminal networks, criminal organizations operating within Myanmar responded to COVID-19’s shock to their operations. This section delves into what factors made cyberscams an optimal choice for criminal adaptation, namely the accessibility of this type of cyberscam and the existence of robust criminal human trafficking networks able to procure free, forced labor. This section explores the kidnap-to-scam operations as a whole, to better understand the pipeline of criminality that these criminal organizations created.

ENTRENCHMENT: This final section assesses the stability of the symbiotic relationship between cyber-enabled criminality and instability, and the parasitic effects both within Myanmar and without. The clearest example of this is the corrupt, quid pro quo relationship established between an ethnic armed organization, the BGF, and these criminal organizations. This relationship closes the feedback loop and entrenches an environment where multiple actors are incentivized toward instability. The instability within Myanmar provides enrichment and safe haven to sow increased instability in various manners and locales; the scam operations themselves create significant financial losses to individuals around the world, the criminal network supporting and supported by these scams contribute to insecurity across Southeast Asia, and the profits from these scams help purchase weapons and supplies that contribute to the protraction of the civil war in Myanmar. Finally, this method of operation as a whole may to inspire armed groups in insecure regions of the world to pursue a path of cybercrime-funded conflict.

Instability: Conflict and Opportunity

Myanmar has been in a state of cyclical violence for decades before the outbreak of the current civil war. This state of violence has created a sustained environment of instability and fertile grounds that opportunistic actors—both criminal syndicates and EAOs—have turned to their advantage.

Understanding the Conflict

On February 1, 2021, the Tatmadaw—the Myanmar military—deposed the democratically elected government headed by the National League for Democracy (NLD) and detained President Win Myint and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi.9Hannah Beech, “Myanmar’s Leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Is Detained Amid Coup,” The New York Times, January 31, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/31/world/asia/myanmar-coup-aung-san-suu-kyi.html; Shibani Mahtani and Kyaw Ye Lynn, “Myanmar Military Seizes Power in Coup after Arresting Suu Kyi,” The Washington Post,” January 31, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/myanmar-aung-sun-suu-kyi-arrest/2021/01/31/c780ce6a-6419-11eb-886d-5264d4ceb46d_story.html. The Tatmadaw declared a state of emergency and called new elections at the end of that year.10Bill Chappell and Jaclyn Diaz, “Myanmar Coup: With Aung San Suu Kyi Detained, Military Takes Over Government,” NPR, February 1, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/02/01/962758188/myanmar-coup-military-detains-aung-san-suu-kyi-plans-new-election-in-2022. In the meantime, Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Min Aung Hlaing took command of the government with a military junta, or military ruling committee.11

The unrest immediately following the coup has since erupted into outright violence between various militarized groups, and against civilians, across Myanmar.11World Report 2023: Events of 2022,” Human Rights Watch, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/myanmar; Frida Ghitis, “As Myanmar’s Crisis Gets Bloodier, the World Still Looks Away,” World Politics Review, September 29, 2022, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/myanmar-civil-war-massacre-coup/; Nada Al- Nashif, “Oral Update on the Human Rights Situation in Myanmar to the Human Rights Council,” September 26, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements-and-speeches/2022/09/oral-update-human-rights-situation-myanmar-human-rights-council; “Myanmar: Military’s Use of Banned Landmines in Kayah State Amounts to War Crimes, Human Rights Watch, July 20, 2022, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/07/myanmar-militarys-use-of-banned-landmines-in-kayah-state-amounts-to-war-crimes/. The primary political challenger to the Tatmadaw government is the National Unity Government (NUG), a shadow civilian government made up of former elected representatives who were ousted or left the Tatmadaw government following the coup. The NUG together with their armed forces, the People’s Defense Force, declared a “people’s defensive war” against the Tatmadaw.12“Myanmar Shadow Government Calls for Uprising against Military,” Al Jazeera, September 7, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/7/myanmar-shadow-government-launches-peoples-defensive-war; Yun Sun, “The Civil War in Myanmar: No End in Sight,” The Brookings Institution, February 13, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-civil-war-in-myanmar-no-end-in-sight/.

PRECIPITATING CONDITION: History of Insecurity

Myanmar has known little respite from conflict and military coups in its history. After gaining independence from the British empire in 1948, a military coup overthrew the fledgling parliamentary democratic Union of Burma in 1962. The ‘70s and ‘80s saw protectionist policies drive a deteriorating economic situation and simultaneously the explosion of corruption and a black-market economy, specifically in drug-producing frontier areas like the Shan state and trafficking corridors in Karen state.13“Myanmar’s Troubled History: Coups, Military Rule, and Ethnic Conflict,” Council on Foreign Relations, last updated January 31, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/myanmar-history-coup-military-rule-ethnic-conflict-rohingya. These same regions featured an ongoing contest of control between the junta and ethnic armed organizations (EAO).14Richard M. Gibson and John B. Haseman, “Prospects for Controlling Narcotics Production and Trafficking in Myanmar,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 25 (2003): 1–19, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25798625. Widespread protests in 1988 led to brutal crackdowns by the junta and a promise of multiparty elections in 1988, which did not occur until 1990, and the results of which the junta ignored, arresting opposition politicians and consolidating power.15Cormac Mangan, Private Enterprises in Fragile Situations: Myanmar, International Growth Centre, June 14, 2018,https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2018/06/Myanmar-case-study.pdf; “As Myanmar Opens Up, A Look Back On A 1988 Uprising,” NPR, August 8, 2013, https://www.npr.org/2013/08/08/209919791/as-myanmar-opens-up-a-look-back-on-a-1988-uprising. Various forms of junta remained in power through 2015, even after widely celebrated election brought the National League for Democracy into majority rule.16The Junta Retained Control and Authority over Security, Foreign Relations, and other Domestic Policy Issues; “Myanmar’s Troubled History: Coups.”

Since February 2021, the United States Institute of Peace and Human Rights Watch estimate that 3,000 civilians have been killed, 20,000 civilians have been arrested, and more than one million people have been displaced, both internally and externally.17Human Rights Watch, World Report 2023. Government control throughout Myanmar is fractured. The junta estimated last year that the Tatmadaw maintained effective control over only 22 percent of Myanmar townships (17 percent of the country’s land area) and partial control over 39 percent of townships ( 31 percent of the land area).18“Briefing Paper: Effective Control in Myanmar,” Special Advisory Council for Myanmar, September 5, 2022, https://specialadvisorycouncil.org/2022/09/statement-briefing-effective-control-myanmar/. Regions across Myanmar controlled by EAOs exploded from a handful in 2021 to large swaths outside of a government-controlled central and southwestern core.19Kim Jolliffe, “Myanmar’s Military Is No Longer in Effective Control of the Country,” May 3, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/05/myanmars-military-is-no-longer-in-effective-control-of-the-country/.; “Situation Maps: The Burma Army’s Authority Deteriorates as It Struggles to Maintain Control within the Country | Free Burma Rangers,” April 24, 2023, https://www.freeburmarangers.org/2023/04/24/situation-maps-the-burma-armys-authority-deteriorates-as-it-struggles-to-maintain-control-within-the-country/. The Myanmar government has cyclically engaged in conflict to assert control against ethnic armed groups in various regions.20Yun Sun, The Civil War in Myanmar. Now, both the Tatmadaw and the NUG rely on a series of carefully balanced alliances made up of such regionally aligned EAOs.21“Myanmar’s Ethnic Armies, Resistance Forces Plan to Boost Operations,” VOA News, February 17, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/myanmar-ethnic-armies-resistance-forces-plan-to-boost-operations/6445835.html.

In the Karen state, there are two main armed groups: the Karen National Union (KNU) and the Karen Border Guard Forces (BGF). One of the oldest EAOs in Myanmar, the KNU, has controlled key territory in the Karen state along the Thai-Myanmar border since 1949. After cyclical antigovernment violence, the KNU signed a ceasefire in 2015 and led ten other ethnic armed groups in the peace process.22“Karen National Union (KNU),” Myanmar Peace Monitor, June 6, 2013, https://mmpeacemonitor.org/1563/knu/. Following the February 2021 coup, the KNU began fighting in open collaboration with the NUG against the Tatmadaw.23Shona Loong, The Karen National Union in Post-Coup Myanmar, Stimson Center, April 7, 2022, https://www.stimson.org/2022/the-karen-national-union-in-post-coup-myanmar/.

On the other side of the conflict, the BGF comprises units of former insurgents that are now aligned with the Tatmadaw and patrol areas of control along the Thai-Myanmar border including important trade corridors. The BGF is seen as a key force multiplier against the KNU and similar groups.24Priscilla A. Clapp and Jason Towever, The Myanmar Army’s Criminal Alliance, The United States Institute of Peace, March 7, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/03/myanmar-armys-criminal-alliance. The commanders of various BGF units operate with relative independence from the junta, often more as protection rackets for businesses—both legitimate and criminal—operating within their jurisdiction.25Jason Tower and Priscilla A. Clapp, Myanmar: Casino Cities Run on Blockchain Threaten Nation’s Sovereignty, The United States Institute of Peace, July 30, 2020, https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/07/myanmar-casino-cities-run-blockchain-threaten-nations-sovereignty. The two warring sides, KNU and NUG versus BGF and Tatmadaw, are unwilling to cede an important trade corridor to Thailand and China alongside the legitimate and illegitimate economic opportunities of the area.

The Tatmadaw and antigovernment forces have increasingly relied on alternative funding sources as the civil war grinds on.26Sreeparna Banerjee and Tarushi Singh Rajaura, Growing Chinese Investments in Myanmar Post-Coup, Observer Research Foundation, accessed November 9, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/growing-chinese-investments-in-myanmar-post-coup/. Tatmadaw’s efforts have been guided toward putting pressure on antigovernment funding with the goal of fracturing the NUG’s alliances and networks with EAOs.27Przemysław Gasztold and Michał Lubina, “Myanmar One Year after the Coup. Interview with Professor Michał Lubina,” Security and Defence Quarterly 38 (June 30, 2022): 86–93, https://securityanddefence.pl/Myanmar-one-year-after-the-coup-Interview-with-Professor-Michal-Lubina,149827,0,2.html. The NUG relies almost exclusively on donations from supporters both within and without Myanmar.28International Crisis Group, “Crowdfunding a War.” To cut off the NUG’s social media funding drives, the Tatmadaw in 2022 restricted mobile payments29“Myanmar Junta Restricts Mobile Money Payments to Cut Resistance Funding,” The Irrawaddy, August 18, 2022, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-restricts-mobile-money-payments-to-cut-resistance-funding.html. and in 2023 passed a cybersecurity law that banned VPN usage, throttled access to social media sites, and forced internet companies to hand over user data to the military.30Sebastian Strangio, “Myanmar Junta Set to Pass Draconian Cyber Security Law,” The Diplomat, January 31, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/myanmar-junta-set-to-pass-draconian-cyber-security-law/. Despite protests from businesses and civil society, the cybersecurity law represents a check to the antigovernment forces’ ability to crowdfund and an attempt to diminish the NUG’s social media presence. The Tatmadaw, the NUG, and the various EAOs are competing not only for military and territorial control, but also for access to financial streams that are otherwise unrestrained by the unrelenting instability.

Criminal Adaptation

Criminal syndicates and the power they wield in Myanmar is not a new phenomenon. However, the character of this criminal adaptation in Myanmar’s Karen state exemplifies how cyber tools can provide an alternate path forward for both criminal syndicates and EAOs. Zeroing in on the Shwe Kokko economic zone, these criminal syndicates have responded to their unstable environment and successive shocks by developing a new, large-scale operation using trafficked labor to scam individuals around the world for millions of dollars a year. This adaptation to the instability in Myanmar appears so effective that their profitability is anecdotally positively correlated with diminished rule of law and security.

Illicit Economic Development

The period from 2011 to 2020 saw limited economic and political reforms including amnesty to political prisoners and reinvigorated economic policies to encourage foreign direct investment.31Annual Democracy Report 2019: Democracy Facing Global Challenges, V-Dem Institute, May 2019, https://www.v-dem.net/documents/16/dr_2019_CoXPbb1.pdf. V-Dem Institute‘s Annual Democracy Report in 2019 emphasized that from 2008 to 2018 Myanmar had moved from a “closed autocracy” to an “electoral autocracy,” and through a lifting of sanctions and trade restrictions, the Myanmar economy experienced modest growth through 2016.32V-Dem Institute, Democracy Facing Global Challenges.; Cormac Mangan, Private Enterprises in Fragile Situations: Myanmar, International Growth Centre, June 14, 2018, https://www.theigc.org/publications/private-enterprises-fragile-situations-myanmar. These legitimate attempts to revitalize the economy, however, were frequently coopted by established criminal networks that used the development money to further their own operations.

PRECIPITATING CONDITION: History of Corruption

Illicit markets, especially drag trafficking, produce profits that have directly financed and enabled EAOs to defy and challenge Myanmar government control for many decades, and over that time have in cases been better armed and resourced than the central government.33Gibson and Haseman, “Prospects for Controlling Narcotics Production.” During this time the ease of entry into the opium trade, the widespread demand for opium and heroin, and the lack of law enforcement on both sides of the Myanmar-Thailand border cultivated massive illicit trading networks.34Patrick Meehan, “Drugs, Insurgency and State-Building in Burma: Why the Drugs Trade Is Central to Burma’s Changing Political Order,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 42 (2011): 376–404, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23020336.

Decades of fighting with these EAOs was temporarily halted by a 1989 ceasefire following the splintering of the largest drug-funded insurgency, the Burma Communist Party. This agreement, which would subsequently serve as the basis for ceasefires with other insurgency groups, granted the BCP’s successor groups significant political and economic autonomy as well as tangible development economic assistance programs.35Gibson and Haseman, “Prospects for Controlling Narcotics Production.” Following the ceasefires, state-controlled banks accepted deposits regardless of the murkiness of the money’s origins in exchange for a 40% (subsequently 25%) fee, helped these organizations and their subsidiaries get business permits and government contracts, and offered lucrative positions in business and government to influential insurgent leaders.36Meehan “Drugs, Insurgency and State-Building,” 376–404. The fighting stopped, but the EAO’s now effectively had carte blanche to develop their criminal operations unhindered, and the government now profited, too, from the expanded illicit trade. Illicit markets in some areas were so profitable that it dwarfed the formal economies of entire regions, providing little incentive for officials to crack down without heavy federal pressure.37”Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State,” International Crisis Group, January 8, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/299-fire-and-ice-conflict-and-drugs-myanmars-shan-state.

In 2015, the government began an aggressive economic development effort along its borders using SEZs to drive international investment and foster domestic economic growth. One such economic zone is Shwe Kokko in Karen state, which has since emerged as a center for legal and illegal gambling and illicit trade.38“Online Scam Operations and Trafficking into Forced Criminality in Southeast Asia: Recommendations for a Human Rights Response,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2023, https://bangkok.ohchr.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/ONLINE-SCAM-OPERATIONS-2582023.pdf. Shwe Kokko was developed by Yatai International in partnership with BGF’s Chit Linn Myaing.39Debby S. W. Chan, “As Myanmar Coup Intensifies Regional Human Trafficking, How Will China Respond?,” The Diplomat, August 23, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/as-myanmar-coup-intensifies-regional-human-trafficking-how-will-china-respond/. Yatai International, a mining and manufacturing company, holds 20 percent stake in the Shwe Kokko development located next door to BGF headquarters.40Han, “The Business of the Kayin State Border Guard Force.”; “Chit Lin Myaing Mining & Industry Co.,Ltd”, OpenCorporates, last updated July 12, 2017, https://opencorporates.com/companies/mm/1605-2005-2006. Yatai International Holding Group is owned by a Chinese national with Cambodian citizenship She Zhijiang and, according to the Yatai’s materials, the development “represents a new chapter for the Belt and Road Initiative”(BRI) within a new Special economic zone.41“Commerce and Conflict: Navigating Myanmar’s China Relationship,” International Crisis Group, March 30, 2020, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/305-commerce-and-conflict-navigating-myanmars-china-relationship; The Myanmar government officially recognizes and advertises three different SEZs within its borders: Kyauk Phyu in Rakhine State, Dawei in the Thanintharyi Region, and the Thilawa in Yangon Region. The three Burmese SEZs host mainly vehicle manufacturing plants from Japan, amid other foreign investment from Singapore, Thailand, and others, totaling $362.28 million in the 2018-19 fiscal year; “Special Economic Zones,” Directorate of Investment and Company Administration, accessed October 17, 2023, http://www.dica.gov.mm/en/special-economic-zones; Yuichi Nitta, “Race for Myanmar’s Auto Market Heats up as Toyota Builds Factory,” – Nikkei Asia, accessed October 17, 2023, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Automobiles/Race-for-Myanmar-s-auto-market-heats-up-as-Toyota-builds-factory.; “Japan Tops List of Foreign Investors in Myanmar SEZs,” November 2, 2019, https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1769224/japan-tops-list-of-foreign-investors-in-myanmar-sezs.

It is unclear, however, how much Yatai’s claims are based in reality. According to the Myanmar Investment Commission, there is no official Special Economic Zone in Shwe Kokko, and legally speaking developments in this area are residential villas.42International Crisis Group, “Commerce and Conflict.” Additionally, a 2020 US Senate report stated that Shwe Kokko is “an effort by the [People’s Republic of China] to colonize Karen [Kayin] territory … and expand regional BRI investments in Southeast Asia,” and links these investments to a broader Chinese strategy to increase its influence throughout the region through BRI.43Committee on Appropriations, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Bill of 2020, S. Rep. No. 116-126 (2019). The Chinese government, however, denied any official state investment in Shwe Kokko.44Chan, “As Myanmar Coup Intensifies.”

Credit: Google Earth

Though SEZs are a legitimate mechanism for driving international investment, those in Myanmar and along the surrounding borders operate more like criminal safe havens with the controlling companies largely shielded from governmental pressures to regulate activities and crack down on criminal organizations.45Jason Tower and Priscilla A. Clapp, Chinese Crime Networks Partner with Myanmar Armed Groups, United States Institute of Peace, April 20, 2020, https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/04/chinese-crime-networks-partner-myanmar-armed-groups; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Online Scam Operations.” The National League for Democracy government was, in fact, conducting an investigation into the connections between the Shwe Kokko development and the BGF.46Zachary Abuza, “Will the First Myanmar Border Guard Defection Have a Contagion Effect?,” Radio Free Asia, June 27, 2023, https://www.rfa.org/english/commentaries/myanmar-border-guard-06272023092414.html. Tensions stemming from the investigation were such that, in 2020, the BGF leadership considered breaking its alliance with the government and resuming fighting in Karen state.47Frontier, “With Conflict Escalating.” Ultimately, the investigation was never concluded.

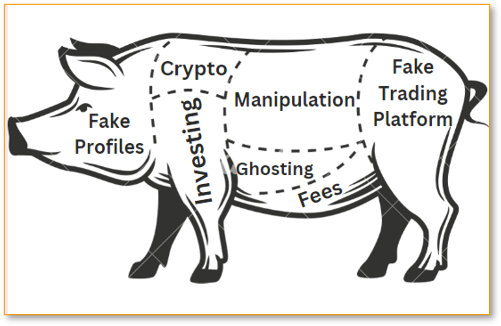

The casinos of Shwe Kokko, and the illicit market that flourished alongside them, were a petri dish of criminal activity, connected with a regional illicit economy. Among these criminal activities were cyberscam operations run by Chinese and local criminal syndicates targeting primarily Chinese nationals.48“The Massive Phone Scam Problem Vexing China and Taiwan,” BBC News, April 22, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36108762; Tessa Wong, Bui Thu, and Lok Lee, “Cambodia Scams: Lured and Trapped into Slavery in South East Asia,” BBC News, September 21, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62792875. These operations largely fell under the category of pig butchering scams, which combine romance and boiler room (or false investment) scams through fake accounts on social media.49Wong, Thu, and Lee, “Cambodia Scams;” “Cryptocurrency Scam – Pig Butchering,” Michigan Department of Attorney General, accessed October 17, 2023, https://www.michigan.gov/ag/consumer-protection/consumer-alerts/consumer-alerts/scams/cryptocurrency-scam-pig-butchering. This network of operations would serve as an unexpected foundation for both these criminal syndicates and the BGF in the tumultuous years to come.

Kidnap-to-Scam

In early 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 almost immediately altered the economic situation on the ground in Southeast Asia. There were no longer visitors to their casinos whose money could be siphoned off through gambling or illegal trade, and profitable trade gates that facilitated traffic between Myanmar and Thailand were forced to close.50Naw Betty Han and Thomas Kean, “On the Thai-Myanmar Border, COVID-19 Closes a Billion-Dollar Racket,” Frontier Myanmar, June 6, 2020, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/on-the-thai-myanmar-border-covid-19-closes-a-billion-dollar-racket/; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Online Scam Operations.” The Bali Process Regional Support Office, “Trapped in Deceit.” Relatively small-scale pig-butchering cyberscams—targeting fewer victims both as forced operators and as cryptoscam marks—were conduct in this area, primarily targeting Chinese nationals. However, the impact diminished due to China’s COVID-19 travel restrictions in 2020 and its counter-cybercrime laws and operations.51Matt Blomberg, “Chinese Scammers Enslave Jobless Teachers and Tourists in Cambodia,” Reuters, September 16, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/cambodia-trafficking-unemployed/feature-chinese-scammers-enslave-jobless-teachers-and-tourists-in-cambodia-idUSL8N2PP21I; Wong, Thu, and Lee, “Cambodia Scams;” “Cambodian Police Raid Alleged Cybercrime Trafficking Compounds,” September 21, 2022, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/cambodian-police-raid-alleged-cybercrime-trafficking-compounds-2022-09-21/; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Online Scam Operations.”

In this changed environment, criminal syndicates had to adapt to find an alternative, steady income stream. These syndicates still had relative safe harbor and physical headquarters in Shwe Kokko and access through their widespread criminal operations to a human trafficking network with a new pool of victims.52The Bali Process Regional Support Office, “Trapped in Deceit.” Cybercrime is so appealing for criminals and criminal groups due in large part to the ability to create mass profit with relatively small resource input, from anywhere in the world. Instead of investing in technically sophisticated capabilities, these criminal syndicates instead used the resource they had in near abundance —forced labor—to conduct a global cyberscam operation. Cyberscams, run by these criminal syndicates out of empty hotels and casinos, became a multimillion-dollar criminal enterprise by exploiting thousands of vulnerable people in Myanmar and Southeast Asia and forcing them in turn to exploit people all around the world.53United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Online Scam Operations.

PRECIPITATING CONDITION: Established Criminal Networks

Transnational organized crime networks across Southeast Asia are engaged in a wide variety of criminal activity, four of the most active including drug trafficking, illegal migration, human trafficking, counterfeit goods and medicines, and environmental crimes.54“Transnational Organized Crime in Southeast Asia: Evolution, Growth and Impact,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, July 18, 2019, https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/archive/documents/Publications/2019/SEA_TOCTA_2019_web.pdf. These criminal syndicates are deeply rooted in locales across Southeast Asia and Myanmar where their operations face minimal threat from governing bodies or law enforcement. The revenue of the drug trafficking out of Myanmar’s Shan state significantly outsizes the state’s legitimate economy.55“Transnational Crime and Geopolitical Contestation along the Mekong,” International Crisis Group, August 18, 2023, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/332-transnational-crime-and-geopolitical-contestation-mekong. Chinese criminal syndicates have operated out of areas like Shwe Kokko in Myanmar and Cambodia for more than a decade in a self-reinforcing cycle in part “created by the confluence of Chinese money, Chinese organized crime groups, and a very poor legal environment,” says the head of the Northern Australia Strategic Policy Centre, John Coyne.56Matt Blomberg, “Chinese Scammers Enslave Jobless Teachers and Tourists in Cambodia,” Reuters, September 16, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/cambodia-trafficking-unemployed/feature-chinese-scammers-enslave-jobless-teachers-and-tourists-in-cambodia-idUSL8N2PP21I; Tessa Wong, Bui Thu, and Lok Lee, “Cambodia Scams: Lured and Trapped into Slavery in South East Asia, BBC News, September 21, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62792875.

The Global Organized Crime Index ranks Myanmar third of 193 countries and first in Asia when it comes to degree of organized criminality.57“Myanmar profile,” Global Organized Crime Index,” accessed October 23, 2023, https://ocindex.net/country/myanmar. Myanmar has consistently rated as among the worst rated locations for human trafficking according to the US Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. The country has been ranked as Tier Three since 2015, meaning that is it included as one of just eleven “governments with a documented “policy or pattern” of human trafficking, trafficking in government-funded programs, forced labor in government-affiliated medical services or other sectors, sexual slavery in government camps, or the employment or recruitment of child soldiers.”58US Department of State, Trafficking in Persons Report, July 2022, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/20221020-2022-TIP-Report.pdf. Myanmar’s role as a hotbed of criminality, though briefly reduced in the mid-2010s, goes back decades and for now, any reduction in the strength of organized crime is next to impossible.59Priscilla A. Clapp and Jason Tower, Myanmar’s Criminal Zones: A Growing Threat to Global Security, The United States Institute of Peace, November 9, 2022, https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/11/myanmars-criminal-zones-growing-threat-global-security.

Since 2020, the groups kidnapped thousands of individuals from across Southeast Asia and beyond and forced them to engage in cybercriminal scams.60“The FBI Warns of False Job Advertisements Linked to Labor Trafficking at Scam Compounds,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, May 22, 2023, https://www.ic3.gov/Media/Y2023/PSA230522#fn1. Thousands of people who had moved within the region, unemployed due to the halt in tourism became what labor abuse investigator Khun Tharo called “invisible people,” extremely vulnerable to the lures employed by local criminal syndicates and without protection.61Blomberg, “Chinese Scammers.” Many of the victims are young, well-educated, computer-literate, and multilingual; and while they struggled to find gainful employment during the pandemic, their skills make them desirable targets for this type of work.62Wong, Thu, and Lee, “Cambodia Scams;” Reuters, “Cambodian Police Raid,”; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Online Scam Operations.” Once these individuals arrived at the advertised location, eager to start new skilled positions with the promised competitive salaries, they are forcibly transported to heavily guarded compounds and their phones and passports are taken away.63“More than 50 Malaysians Held Captive by Syndicates in Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam and Thailand, says MCA’s Michael Chong,” Malay Mail, April 7, 2022, https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2022/04/07/more-than-50-malaysians-held-captive-by-syndicates-in-cambodia-myanmar-viet/2052138; “Malaysian Job Scam Victim Tells of ‘Prison’, Beatings in Myanmar,” The Straits Times, May 18, 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/job-scam-victim-tells-of-prison-beatings-in-myanmar; Sokvy Rim, “The Social Costs of Chinese Transnational Crime in Sihanoukville,” The Diplomat, July 5, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/07/the-social-costs-of-chinese-transnational-crime-in-sihanoukville/; Blomberg, “Chinese Scammers;” Wong, Thu, and Lee, “Cambodia Scams;” The Economist, “The Gangs that Kidnap;”, Lindsey Kennedy, Nathan Paul Southern, and Huang Yan, “Cambodia’s Modern Slavery Nightmare: the Human Trafficking Crisis Overlooked by Authorities” The Guardian, November 2, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/03/cambodias-modern-slavery-nightmare-the-human-trafficking-crisis-overlooked-by-authorities; The Bali Process Regional Support Office, “Trapped in Deceit;” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Online Scam Operations.” Once trapped inside, victims were told that their new role was to engage in a number of online pig butchering scams to generate sufficient profit for their captors. Victims deemed to be disobedient or underperforming are beaten and tortured by electrocution and other inhumane methods.64Chan, “As Myanmar Coup Intensifies;” Wong, Thu, and Lee, “Cambodia Scams;” AFP, “Inside the ‘Living Hell’ of Cambodia’s Scam Operations,” France 24, November 9, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20221109-inside-the-living-hell-of-cambodia-s-scam-operations.

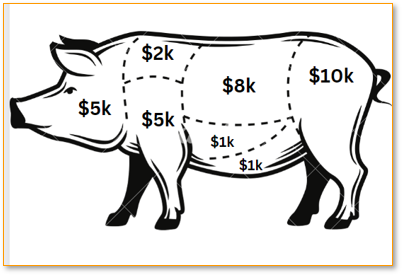

Pig butchering scams typically require intensive time and relationship building, and trafficked individuals are forced to build these relationships over time, partially through the use of playbooks and scripts made for the kidnapped workforce.65Lily Hay Newman, “Hacker Lexicon: What Is a Pig Butchering Scam?” WIRED, January 2, 2023, https://www.wired.com/story/what-is-pig-butchering-scam/; Cezary Podkul, “What’s a Pig Butchering Scam? Here’s How to Avoid Falling Victim to One,” ProPublica, September 19, 2022, https://www.propublica.org/article/whats-a-pig-butchering-scam-heres-how-to-avoid-falling-victim-to-one; The Economist, “The Gangs that Kidnap.” The term pig butchering refers to the scammers’ process of first feeding the victim or ‘pig’ with false information until it is ready for the scam, then the scammer steals, or ‘butchers,’ the victim’s information and money. Typically, these pig butchering scams involve investments in cryptocurrency where the victim will be prompted to download a malicious app or create an account on a web platform that appears trustworthy or as a counterfeit of a legitimate financial institution.66Newman, “Hacker Lexicon;” An analysis of one pig butchering scam network’s cryptocurrency wallets by TRM Labs showed that victim funds are usually sent in the form of Tether on Ethereum, with a smaller percentage using bitcoin or Tether (USDT) on Tron, see “Pig Butchering Scams: What the Data Shows,” TRM,” accessed October 17, 2023, https://www.trmlabs.com/post/pig-butchering-scams-what-the-data-shows. Inside the app or platform, the victim is shown carefully crafted data demonstrating that their ‘financial investment’ has grown and is encouraged to add more funds with the promise they can withdraw at any point. Once the victim has deposited a significant amount of money and shows signs of insolvency, the scammers will shut down the account and disappear, leaving the victim without recourse and often in debt.67ProPublica, “What’s a Pig Butchering Scam?”

Entrenchment

While these cyberscam operations create symbiotic benefit for both criminal groups and EAOs in Myanmar, the operations themselves are intensely parasitic to the global cyber domain, the broader Southeast Asian region, and the population of Myanmar. Finally, this paper explores how this relationship could serve as an analytic model to better understand criminal-combatant relationships elsewhere in the world where similar precipitating conditions and patterns are present.

Global Financial Impact

The 2023 National Cybersecurity Strategy highlighted, along with China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, the threat that global criminal syndicates pose to US national security, especially those threats emanating from jurisdictions with ineffective or irresponsible rule of law.68“National Cybersecurity Strategy,” White House, March 2, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/National-Cybersecurity-Strategy-2023.pdf. Though the strategy’s section on countering cybercrime focuses primarily on ‘defeating ransomware,’ the strategy emphasizes the dangers of cyber operations that target the most vulnerable and least defended. The cyberscam operations run out of Myanmar are not technically sophisticated, and yet generate incredible gross and net profit—underlining the tenuous link between sophistication and the financial yield from cybercrime.

Several studies from governments and nongovernmental groups over the past few years have tried to illustrate the global financial impact of the scams as a whole, and particularly those emanating from Southeast Asia. In 2021, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Internet Crime Complaint Center received 4,325 complaints from US residents and citizens regarding pig butchering scams, reporting collective losses over $429 million.69“Internet Crime Report 2021,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, March 2021, https://www.ic3.gov/media/PDF/AnnualReport/2021_IC3Report.pdf. The Global Anti-Scam Organisation (GASO)—founded and maintained by victims of these pig butchering scams—conducted a survey through July 6, 2022, to better understand individual victims’ losses. Within the United States, the survey found that the average victim lost $210,760 and the median victim lost $100,000; outside of the United States the average and median were slightly lower, $155,117 and $52,000, respectively. The study also found that of the surveyed victims, 24 percent lost less than 50 percent, 43 percent lost between 50-100 percent, and 33 percent lost more than their net worth and went into debt as a result of the scam.70Cannabiccino, “Statistics of Crypto-Romance / Pig-Butchering Scam,” Global Anti-Scam Organisation, updated July 7, 2022, https://www.globalantiscam.org/post/statistics-of-crypto-romance-pig-butchering-scam. In several reported cases, scam victims lost more than $1 million,71Robert McMillan, “A Text Scam Called ‘Pig Butchering’ Cost Her More Than $1.6 Million”Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-text-scam-called-pig-butchering-cost-her-more-than-1-6-million-11666258201; Alastair McCready, “From Industrial-Scale Scam Centers, Trafficking Victims Are Being Forced to Steal Billions,” VICE News, July 13, 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7zb5d/pig-butchering-scam-cambodia-trafficking. and in one case a victim lost a staggering $5 million dollars.72Brian Krebs, “Massive Losses Define Epidemic of ‘Pig Butchering’,” Krebs on Security,” July 21, 2022, https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/07/massive-losses-define-epidemic-of-pig-butchering/. These figures, though not comprehensive, clearly telegraph the global economic impact of this relatively simple cyberscam.

Although little research has been conducted on these scams’ profits in Myanmar in particular, figures on related scams coming out of Cambodia may provide a comparative scale, at least, of the profits from similar operations conducted out of Myanmar. According to a 2022 report from VICE News, pig butchering kidnap-to-scam operations operated from Sihanoukville, Cambodia generate approximately $1 billion every year.73McCready, “From Industrial-Scale Scam Centers.” Sean Gallagher, a principal threat researcher at Sophos X-Ops posing as a ’duped’ victim of a one such scam based in Sihanoukville, Cambodia, allowed the scam operator over the course of five months to play out a script of trust building until she provided him instructions in the form of friendly advice for how to invest in cryptocurrency. During his investigation, he found a series of crypto wallets used by the scammers over a five-month period worth a collective $3 million.74Sean Gallagher, “Sour Grapes: Stomping on a Cambodia-Based ‘Pig Butchering’ Scam,” Sophos News (blog), February 28, 2023, https://news.sophos.com/en-us/2023/02/28/sour-grapes-stomping-on-a-cambodia-based-pig-butchering-scam/.

Exacerbating Regional Insecurity

These kidnap-to-scam operations have deep regional repercussions and interconnections. Myanmar’s neighbors across Southeast Asia are also the places from which these criminal syndicates pull most of their initial victims, thousands from Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, and more.75“Forced to Eat Rats and Pork, Malaysian Job-scam Victim Recounts Harrowing Captivity in Myanmar,” Coconuts KL, January 23, 2023, https://coconuts.co/kl/news/forced-to-eat-rats-and-pork-malaysian-job-scam-victim-recounts-harrowing-ordeal-during-captivity-in-myanmar/; Ouch Sony, “3,000 Thais to Be Repatriated From Cambodian Scam Compounds: Thai Police,” VOD, March 29, 2022, https://vodenglish.news/3000-thais-to-be-repatriated-from-cambodian-scam-compounds-thai-police/; Yan Naing, “Chinese Gangs Exploiting Vulnerable People Across Southeast Asia,” The Irrawaddy, May 2, 2022, https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/guest-column/chinese-gangs-exploiting-vulnerable-people-across-southeast-asia.html; Sony, “3,000 Thais to Be Repatriated.” Victims across the region and beyond are sucked into this multinational human trafficking network—lured to Thailand or other seemingly safe locations, and there, kidnapped and transported to scam compounds in Myanmar.76International Crisis Group, “Commerce and Conflict;” Hillary Leung, “8 Hongkongers Missing in Myanmar as City Sets up Taskforce to Investigate Alleged Southeast Asia Job Scam,” Hong Kong Free Press, updated August 22, 2022, https://hongkongfp.com/2022/08/18/8-hongkongers-missing-in-myanmar-as-city-sets-up-taskforce-to-investigate-southeast-asia-job-scam-trafficking/; Chan, “As Myanmar Coup Intensifies;” AFP, “Hong Konger ‘Kidnapped’ by SE Asia Scam Ring Pleads for Help,” France 24, August 24, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220824-hong-konger-kidnapped-by-se-asia-scam-ring-pleads-for-help; Raul Dancel, “8 Filipinos Rescued from Myanmar Syndicate Running Cryptocurrency Scams,” The Straits Times, February 13, 2023, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/8-filipinos-rescued-from-myanmar-syndicate-running-cryptocurrency-scams. The criminal syndicates behind most illegal gambling institutions and scam rings remain highly mobile and responsive to law enforcement pressures. These syndicates appear to have strong cross-regional connections that enable them to efficiently move their operation and their victims, and start operations anew—including to Myanmar.77“Inside the ‘living hell’” ; Jintamas Saksornchai and Cindy Liu, “Scam Workers; Wong, Thu, and Lee, “Cambodia Scams.” These groups tend to locate within SEZs or tourist hot spots and expand upon traditional criminal activities.

One such location where there are similar kidnap-to-scam operations is Sihanoukville, Cambodia. After years of local and international pressure, in September 2022 the Cambodian government and law enforcement carried out raids on the casinos and hotels where investigators and former victims were forced to run these scams. However, according to one volunteer who helps repatriate Thai victims, criminal syndicates bought out corrupted officials and law enforcement personnel who would inform the syndicates in advance of raids so that authorities would find the location empty.78Kennedy, Southern, and Yan, “Cambodia’s Modern Slavery.” One victim, initially held in Sihanoukville, Cambodia, reported that he and dozens of other prisoners were moved in the middle of the night and reestablished in Shwe Kokko before his eventual escape.79Jintamas Saksornchai and Cindy Liu, “Scam Workers Relocated From Cambodia to Laos, Myanmar,” VOD, October 24, 2022, https://vodenglish.news/scam-workers-relocated-from-cambodia-to-laos-myanmar/; part of VOD investigative series, Enslaved: Workers Trapped in Cambodian Human-trafficking Hubs are Forced to Perpetuate Massive Global Scams.

A concentrated effort by government and law enforcement is required to detain criminals, rescue kidnapped workers, and shutter the bases of operations that these groups use. However, as the case of Sihanoukville shows, the mobility of and interconnection between these criminal groups means that they can respond easily to governmental pressure in one city or region by shifting workers and operations to a new area with weaker rule of law. This effectively means that regardless of how hard other regional governments target this activity, criminal groups have safe havens where local authorities have financial and political interest in facilitating and benefiting from illicit activities.

Perpetuating Civil War

The 2021 coup in Myanmar and resulting instability were a boon for the BGF and their criminal partners across Karen state. The investigation into Shwe Kokko by the previous government was halted by the Tatmadaw, Karen casinos and border trade depots with Thailand have reopened, and the BGF’s multimillion-dollar developments in and around Shwe Kokko were restarted.80Frontier, “With Conflict Escalating.” The Shwe Kokko casinos resumed operations shortly after the coup in 2021 due to the Karen BGF’s relationship with the Tatmadaw and alleged promises between the parties that profits “would be split in half.”81Frontier, “With Conflict Escalating.” The money from these scams flow mostly to the heads of the crime organizations but also into the pockets of armed ethnic groups or junta-aligned forces that control the areas where the scam centers operate. The commanders of various BGF units operate with relative independence from the Tatmadaw and most operate as protection rackets for businesses, both legitimate and criminal, operating within their jurisdiction.82Jason Tower and Priscilla A. Clapp, Myanmar: Casino Cities Run on Blockchain Threaten Nation’s Sovereignty, The United States Institute of Peace, July 30, 2020, https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/07/myanmar-casino-cities-run-blockchain-threaten-nations-sovereignty. In areas where Tatmadaw or Tatmadaw-aligned military forces control territory, the criminal organizations bribe military members with large sums of money and pay for taxes83“Myanmar: Thai State-Owned Company Funds Junta,” Human Rights Watch, May 25, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/25/myanmar-thai-state-owned-company-funds-junta. and yearly licenses to continue operations.84Dominic Faulder, “Asia’s Scamdemic: How COVID-19 Supercharged Online Crime,” Nikkei Asia, November 16, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/The-Big-Story/Asia-s-scamdemic-How-COVID-19-supercharged-online-crime. Tatmadaw-aligned individuals have also issued licenses for business operations and land leases to front companies associated with scam groups, often in the form of seemingly legitimate tax payments for land, utility, and building use.85“Myanmar Junta Restricts Mobile Money Payments,” The Irrawaddy; “Shwe Kokko Crime Hub Attacked,” The Irrawaddy; Gary Warner, “Please Stop Calling All Crypto Scams ‘Pig Butchering!,’” Security Boulevard, August 1, 2022, https://securityboulevard.com/2022/08/please-stop-calling-all-crypto-scams-pig-butchering/. Entrenchment in and control over Shwe Kokko and related criminal activities may have increased following the arrest of Yatai founder She Zhijiang in August 2022, which left an even greater opening for the BGF.86Feliz Solomon, “A Casino Kingpin Pitched a City in Myanmar—Police Say He Helped Build a Crime Haven,” Wall Street Journal,” September 29, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-casino-kingpin-pitched-a-city-in-myanmarpolice-say-he-helped-build-a-crime-haven-11664450817.

These cryptoscam operations, and those connected with them, have themselves become targets of retaliatory violence. As more information surfaces about money laundering networks, individuals connected with these activities face targeting by anti-regime forces in Myanmar and arrest in other countries.87Poppy McPherson and Panu Wongcha-Um, “Myanmar Junta Chief’s Family Assets Found in Thai Drug Raid, Sources Say,” The Japan Times, January 11, 2023, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/01/11/asia-pacific/myanmar-junta-assets/. Minn Tayzar Nyunt Tin, a legal aide who was allegedly “key to money laundering for the Junta,” was assassinated in Yangon in March 2023 as a direct result of those activities. The Yangon guerrilla group allegedly responsible claimed that Tin had facilitated raising millions of dollars for the Tatmadaw.88Hein Htoo Zan, “Yangon Guerrillas Kill Myanmar Junta Money Laundering Chief,” The Irrawaddy, March 25 2023, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/yangon-guerrillas-kill-myanmar-junta-money-laundering-chief.html. In April 2023, forces associated with the Karen National Union (KNU)89“Kawthoolei Army: How a Broken System and a Disrespect for the Rules of Law in the KNU Gave Birth to Another Armed Group in Karen State,” Karen News, August 2, 2022, https://karennews.org/2022/08/kawthoolei-army-how-a-broken-system-and-a-disrespect-for-the-rules-of-law-in-the-knu-gave-birth-to-another-armed-group-in-karen-state/; MPA, “The KNLA and the Kawthoolei Army (KTLA) Issued Parallelly Statements, and the Attitude of Each Was Tense,” MPA (blog), February 1, 2023, https://mpapress.com/news/17009/. attacked Shwe Kokko, reportedly because of its role as a criminal base of operations funding the military regime.90The Irrawaddy, “Shwe Kokko Crime Hub Attacked.” This attack, allegedly without KNU approval, sent over 10,000 civilians fleeing into Thailand and initially overran five BGF outposts until BGF and Tatmadaw reinforcements forced them to retreat.91“Into the Lion’s Den: The Failed Attack on Shwe Kokko,” Frontier Myanmar, May 11, 2023, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/into-the-lions-den-the-failed-attack-on-shwe-kokko/; “Heavy Fighting between the Military Council and the KNLA in Shwe Kukko,”Burmese VOA, April 7, 2023, https://burmese.voanews.com/a/7040280.html.

After sanctions by the West and increasing international pressure,92Panu Wongcha-um and Poppy McPherson, “Myanmar Activists, Victims File Criminal Complaint in Germany over Alleged Atrocities,” Reuters,” January 24, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/myanmar-activists-victims-file-criminal-complaint-germany-over-alleged-2023-01-24/; “Foreign Companies in Myanmar Struggle with Shortage of Dollars,” Nikkei Asia, September 8, 2022, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Crisis/Foreign-companies-in-Myanmar-struggle-with-shortage-of-dollars. the Tatmadaw faces a funding shortfall93Banerjee and Rajaura, “Growing Chinese Investments;” Aradhana Aravindan, “Myanmar’s Economic Woes Due to Gross Mismanagement since Coup – U.S. Official,” Reuters,” October 20, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/myanmars-economic-woes-due-gross-mismanagement-since-coup-us-official-2021-10-20/. and difficulties in procuring weapons and ammunition.94US Department of Treasury. ”Treasury Sanctions Officials and Military-Affiliated Cronies in Burma Two Years after Military Coup.” Department of Treasury press release, January 31, 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1233; Michael Martin, “News from the Front: Observations from Myanmar’s Revolutionary Forces,” The Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 5, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/news-front-observations-myanmars-revolutionary-forces. Russia and China both supply weapons to the Tatmadaw, but Russia’s export of weapons has slowed since its invasion of Ukraine, and China’s contributions are in part counterbalanced by weapon provisions they also make to several rebel EAOs.95Michael Martin, “Is Myanmar’s Military on Its Last Legs?,” The Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 21, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/myanmars-military-its-last-legs. Chinese support of the Tatmadaw is being challenged due to the Tatmadaw’s lack of interest or ability to tackle the crime emanating from within Myanmar’s borders. Earlier this year, two Chinese ambassadors urged Myanmar to curtail these harmful illegal activities, possibly in conjunction with the Thai government.96“Qin Gang: China Hopes Myanmar Will Crack Down on Internet Fraud,” Ministry of Foreing Affairs of the Republic of China, accessed October 23, 2023, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb_663304/wjbz_663308/activities_663312/202305/t20230504_11070146.html; Sylvie Zhuang, “China Urges Myanmar to Crack Down on Telecoms Fraud Luring Victims over Border,” South China Morning Post, March 24, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3214714/china-urges-myanmar-crack-down-telecoms-frauds-luring-victims-across-border. In addition, in early September, the United Wa State Army, carried out a series of raids in in northern Myanmar’s Shan state, arresting “more than 1,200 Chinese nationals allegedly involved in criminal online scam operations” and handing them over to the Chinese police just across the border in China’s Yunan province.97“Powerful Ethnic Militia in Myanmar Repatriates 1,200 Chinese Suspected of Involvement in Cybercrime,” Associated Press, updated September 9, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/myanmar-cybercrime-wa-online-scams-58082a9f93a24406fa5c3cfbc647b20e. These actions show increasing Chinese momentum against this criminal activity, but it is unclear how this might play out in Karen state. Should the Tatmadaw government attempt to crack down on crime in Shwe Kokko, they will likely further fracture their relationship with the BGF, and thus their hold in the region. The estimated millions of dollars produced in Shwe Kokko kidnap-to-scam operations is an invaluable source of funding to enable the BGF to withstand shocks from within Myanmar and from international action, one they will be loath to lose.

A Model for Cybercrime-Driven Conflict

The catalysts, precipitating conditions, and cyclical patterns of the development and entrenchment of cybercrime-funded conflict within Myanmar are unique to that country. However, many of these factors are not unique and are present in similar configurations in other countries and regions around the world. As more and more criminal and armed groups develop cyber capabilities, some may look to Myanmar as an example. In locales with limited rule of law and a strong criminal human trafficking network, like the criminal syndicates in Myanmar, may see these victims as a resource themselves to conduct immensely profitable cyberscams requiring little additional resources or capabilities. INTERPOL, in its June 2023 warning on human trafficking-fueled fraud, warned that “there is evidence that [this modus operandi] is being replicated in other regions such as West Africa, where cyber-enabled financial crime is already prevalent.”98“INTERPOL Issues Global Warning on Human Trafficking-Fueled Fraud,” INTERPOL, June 7, 2023, https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2023/INTERPOL-issues-global-warning-on-human-trafficking-fueled-fraud. However, this warning does not go far enough. The spread of kidnap-to-scam operations themselves do pose a significant risk to global financial security. With billions of dollars in profit, governments around the world must wake up to the threat of this kind of cyber fraud and its risks to their populations. These operations are rarely confined to one locale, but rather spread across regional criminal networks; when this modus operandi is implemented in a region impacted by violence and instability it creates a self-reinforcing cycle of instability.

Looking Forward – What Can We Do?

Targeting the Point of Collection

Public Awareness

In March 2023, the FBI released a public warning on the rise of pig butchering scams, outlining the basic format of one of these cryptocurrency scams and offering steps for potential victims to protect themselves.99“The FBI Warns of a Spike in Cryptocurrency Investment Schemes,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, March 14, 2023, https://www.ic3.gov/Media/Y2023/PSA230314. While government notifications like these are important, they do not go nearly far enough to communicate the depth of the threat to the wider public in the United States and beyond. Most of the population does not read government alerts, and so the government must coordinate with companies and nonprofits to find people where they are—and where these scammers find them. According to California prosecutor Erin West, cryptoscam victims are most commonly found on dating apps run by Match, Meta’s Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages.100“California Prosecutor Erin West on the Massive Wealth Transfer to Southeast Asia from a Crypto Scam Called ‘Pig Butchering,’” CyberScoop (blog), July 12, 2023, https://cyberscoop.com/erin-west-safe-mode-pig-butchering/. Sites like these should be the focus of the FBI and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) alert and education efforts on cryptocurrency scams, and run in cooperation with Match, Meta, LinkedIn, and other social media platforms. Since these cryptoscams do not solely exploit victims in the United States, the United States should engage with its allies and partners to coordinate their public awareness campaigns.

Education regarding the dangers of cryptocurrency scams should go beyond these alerts. The FBI and the Treasury Department should coordinate with companies like Chainalysis and nonprofit organizations like the Global Anti-Scam Organisation (GASO)101“Latest Scam Websites Information | Global Anti-Scam Org,” Global Anti Scam Org, accessed October 23, 2023, https://www.globalantiscam.org/scam-websites. to create guidelines to help people who want to buy and sell cryptocurrency better identify the signs of fraudulent or exploitative sites. These entities should also work in coordination to create guidelines for how people can report suspicious sites or activity below a formal criminal complaint. Most pig butchering cases go unreported, hindering potential prosecution, and leaving analysts without a full picture of their impact on victims.102TRM Insights, “Pig Butchering Scams.”

United States Government

As previously mentioned, the US 2023 National Cybersecurity Strategy places a priority on countering cybercrime, but is too narrowly focused on ransomware as, seemingly, the only criminal strategic threat. Because cryptoscams target individuals rather than companies, the technical means used are often unsophisticated, and the scams themselves are often left unreported; therefore, the threat of this type of cybercriminal activity is underappreciated. As the CISA and FBI implement what has thus far been laid out in the strategy and implementation plan, their efforts must be intentionally expanded to include pig butchering operations. This may include creating a separate Joint Cryptoscam Task Force with a different mix of government and private sector entities to assess the full picture of the threat. It is critical to streamline communication and efforts between different organizations already tracking this. There are pockets of knowledge about this already, the key here is getting those pockets to talk and coordinate efforts. Specifically, the US Government should work with private sector crypto organizations to better identify funding streams of scam organizations and work with law enforcement and financial entities to close loopholes and enforce Know Your Customer rules.103Daniel Mikkelsen, Shreyash Rajdev, and Vasiliki Stergiou, “Financial Crime Risk Management in Digital Payments, McKinsey, June 24, 2022, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/managing-financial-crime-risk-in-digital-payments.

One such tool may be to echo the successes of counter-ransomware operations to directly target the websites facilitating money laundering for cryptoscams. Steps have already been taken in this direction. In 2022, the United States filed a forfeiture complaint worth $2 million against cryptocurrency seized in an investment fraud case using the RiotX platform.104“U.S. Seeks Forfeiture of Crypto from ‘$2M Asian “Pig Butchering” RiotX Scam’,” OffshoreAlert, September 12, 2022, https://www.offshorealert.com/u-s-seeks-forfeiture-of-crypto-derived-from-2m-pig-butchering-riotx-scam/. In 2023, the FBI announced that it had seized more than $112 million in funds linked to cryptocurrency investment schemes.105US Department of Justice. “Justice Dept. Seizes Over $112M in Funds Linked to Cryptocurrency Investment Schemes, With Over Half Seized in Los Angeles Case. US Department of Justice press release,” April 3, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/usao-cdca/pr/justice-dept-seizes-over-112m-funds-linked-cryptocurrency-investment-schemes-over-half. Once again, this effort should be internationalized so that the United States and its allies and partners are simultaneously applying pressure against the points of cryptocurrency collection for these criminal groups. In particular, the FBI should coordinate with Interpol’s ASEAN desk both to capture and share information and to execute limited, intentional operations against global criminals wherever jurisdiction allows.

The US government should also expand its use of sanctions. In November 2022, the US government, in partnership with the European Union, enacted sanctions against a number of individuals and companies as a result of “the continuing escalation of violence and grave human rights violations following the military takeover [in February 2021],” focusing on government officials, military leaders, and arms dealers.106“US, EU Add More Sanctions as Myanmar Violence Deepens,” Al Jazeera, November 9, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/11/9/us-eu-add-more-sanctions-as-myanmar-violence-deepens. In December 2022, the US government passed the BURMA Act which lays out a series of mandatory and additional sanctions against various individuals and organizations within Myanmar. The mandatory sanctions include senior officials and entities that support the defense sector. The additional “possible” sanctions outlined by this act include:

(4) “any foreign person that, leading up to, during, and since the February 1, 2021, coup d’état in Burma, is responsible for or has directly and knowingly engaged in—

(A) actions or policies that significantly undermine democratic processes or institutions in Burma;

(B) actions or policies that significantly threaten the peace, security, or stability of Burma;

(C) actions or policies by a Burmese person that—

(i) significantly prohibit, limit, or penalize the exercise of freedom of expression or assembly by people in Burma; or

(ii) limit access to print, online, or broadcast media in Burma; or

(D) the orchestration of arbitrary detention or torture in Burma or other serious human rights abuses in Burma; or

(5) any Burmese entity that provides materiel to the Burmese military”107Burma Act of 2021, H.R. 5497, 117th Cong. (2021).

Within these guidelines, the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control should assess this connection between criminal groups, EAOs, and the companies operating within Shwe Kokko as outlined in this paper and determine how specific sanctions may aid in weakening the interplay of crime and violence in the state.

Targeting the Source

Further Research

More research is needed to understand the true financial impact of these operations throughout the world. Existing coverage of the prevalence and financial losses of these operations likely underestimates their true impact due to underreporting. Whether scam victims believe that nothing can be done, do not know how to report the criminal activity, or are too embarrassed to tell anyone, underreporting is a significant problem to overcome before governments and concerned actors can truly understand how to effectively respond.108Rohan Goswami, “That Simple ‘hi’ Text from a Stranger Could Be the Start of a Scam That Ends up Costing You Millions,” CNBC, May 2, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/02/pig-butchering-scammers-make-billions-convincing-victims-of-love.html; Keith B. Anderson, “To Whom Do Victims of Mass-Market Consumer Fraud Complain?,” SSRN, May 24, 2021, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3852323. Research into the profits that pig butchering groups in Myanmar generated in three distinct time periods—before the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020, between that date and the 2021 coup, and since the 2021 coup—would provide an indispensable, quantitative view of how different shocks to the population and criminal groups within the country affected these operations.

Regional Cooperation

As the United States takes action against the threats emanating from criminal entities in Southeast Asia, it must work alongside governments in the region that have been most affected, and affected in different ways, by this threat. The Department of State should coordinate with Southeastern Asian government, especially Thailand and Cambodia, to better understand the scope and depth of the problem they face in cross-regional criminal operations like human trafficking. The Department of State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons must be more vocal to partners and push nations to release public service announcements, prevent citizens leaving for scam jobs, and work with their embassies to rescue citizens. This may also be an opportunity for the United States and China to cooperate against a common threat. China has been working to counter this problem for years, including in cooperation with Thailand in recent mass arrests.109Zhao Ziwen, “Police in China and Myanmar Detain 269 in Cyber Scam Crackdown,” South China Morning Post, September 5, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3233506/police-china-and-myanmar-detain-269-cyber-scam-crackdown. The United States should be clear about the public action it is taking against these groups and attempt, as much as possible, to align these efforts so that they are reinforcing rather than creating redundancies of Chinese and regional efforts.

Conclusion

The kidnap-to-scam operations run by criminal syndicates and enabled by armed combatants in an ongoing civil war, illustrate how cybercrime has become an effective vehicle through which nonstate actors can fund and perpetuate conflict outside of the cyber domain. Criminal syndicates in Myanmar are able to operate effectively due in large part to the vulnerable populations created in unstable environments and the lack of governance and law enforcement oversight. The BGF in Myanmar’s Karen state is able to maintain a level of independence from the Tatmadaw, even as allies, and convert illicit profits from cyberscams into guns and ammunition.110Gibson and Haseman, “Prospects for Controlling Narcotics Production.” The profits that these syndicates generate, at the expense of victims around the globe, add a growing source of fuel to the ongoing civil war in Myanmar and threaten the stability of Southeast Asia.

The use of cybercrime to fund conflict and instability could well become more prevalent as the basic relationship is symbiotic and few of the precipitating conditions are unique to Myanmar. This emerging trend poses a significant risk to the United States and its allies, especially where it undermines important and rapidly hardening assumptions about the nature of risk from insecurity in cyberspace.

Conflict is not exclusive to the cyber or physical realms but increasingly moves across and between domains as combatants and opportunists alike follow clear incentives to marry strategic and financial gain. The United States and its allies must work together to create a clearer picture of the global cybercriminal landscape beyond ransomware and technical mitigations, and work with those governments impacted directly by kidnap-to-scam operations to help curtail this problem at its source. In the absence of such information, the next small wars and civil conflicts may be fueled by a powerful set of relationships and criminal incentives never well examined and all the more powerful because of it.

The Cyber Statecraft Initiative, part of the Atlantic Council Tech Programs, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.