Learning more about platforms from the first Digital Services Act transparency disclosures

An analysis of platform reporting on content moderation teams’ language skills

Learning more about platforms from the first Digital Services Act transparency disclosures

Share this story

Banner: Social media icons logo displayed on a smartphone with European Commission Digital Service Act on screen seen in the background. (Source: Jonathan Raa/NurPhoto via Reuters Connect)

When tech platforms operate globally, building audiences across a range of languages, whether they have content moderation staff capable of speaking those languages and understanding local nuance can impact safety, rights, and democracy around the world. However, absent laws requiring companies to resource their teams at certain levels, articulate how they are managing risk in different markets, or even disclose what capabilities they have, any information the general public and independent researchers have about platform operations have been gleaned through voluntary disclosures and patchwork data.

The European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) seeks to address this issue in a number of ways, but one in particular is through newly required transparency reports. And we’ve just gotten our first peek into what insights this new information can provide. Under Article 42 of the DSA, Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs) are required to specify “the human resources” that they dedicate “to content moderation in respect of the service offered in the Union, broken down by each applicable official language of the Member States.” The law requires reporting on “the qualifications and linguistic expertise” of the content moderators and “the training and support given to such staff.” This is understood to mean all human resources, whether full-time staff or contract support. This is a remarkable provision in the DSA, because it sheds light on how platforms think about – and, ultimately, deal with – the multilingual aspects of content moderation. While a basic count of staff and language skills is certainly only part of the picture, knowing how platforms compare to one another and being able then to apply that information to other factors enriches everyone’s understanding of what matters in making our digital world one that works for us.

Language capacity in the first round of transparency reports

Following the November 6, 2023, deadline set by the Commission, all seventeen VLOPs and two VLOSEs released the first round of transparency reporting. The reports included information on platform content moderation practices, ranging from metrics on government requests like takedowns to staffing levels and language competency.

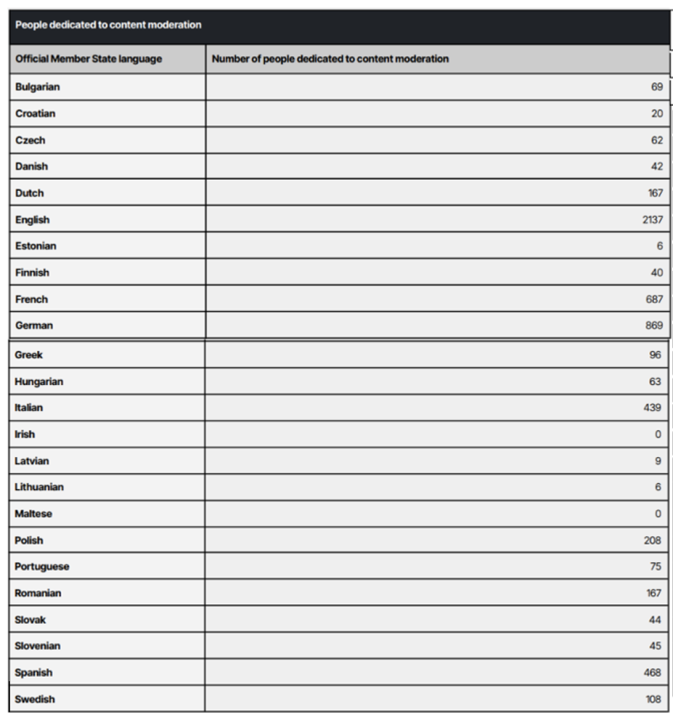

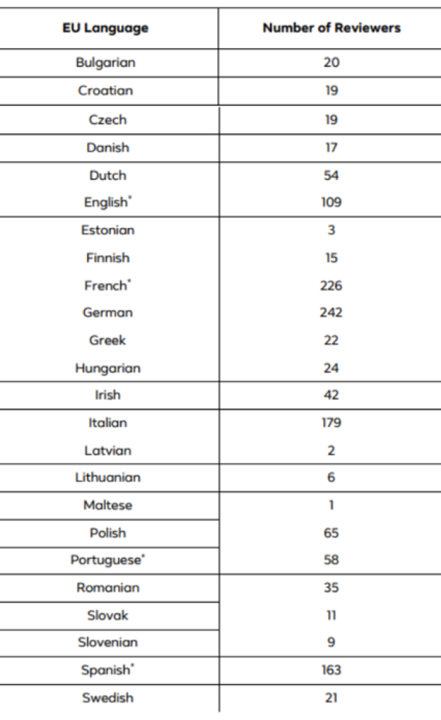

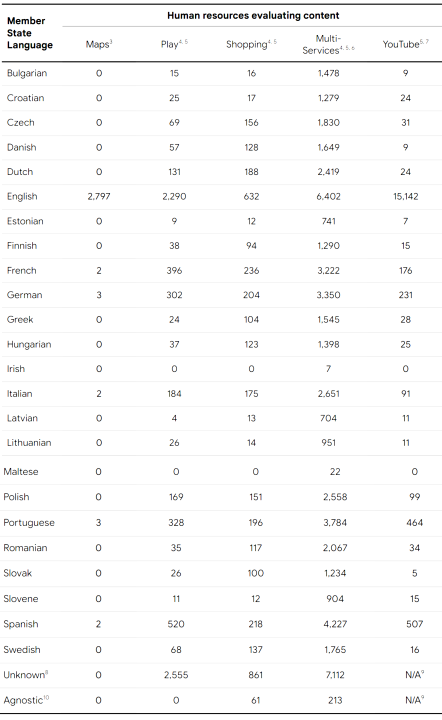

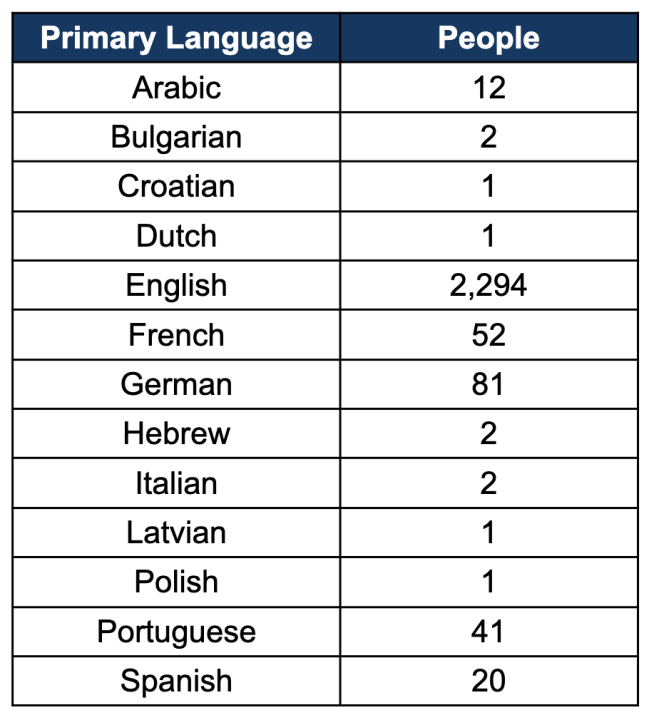

As we seek to better understand how the DSA may be applied in the future, and what kinds of reporting from companies can matter the most, this piece provides a quick snapshot of disclosures from six well-known social media platforms – X, Meta, TikTok, LinkedIn, Snapchat, and Google – reflecting just one aspect of the new transparency reporting requirements; the number of content moderators and their language capacities.

While the DSA certainly will have global ramifications and create opportunities for everyone to learn more about platforms, in the end, the DSA is European regulation aimed at ensuring the rights and interests of European citizens. To this end, Article 42 requires platforms to report their content moderation capacities for the twenty-four official languages of the EU. While some platforms seemed to have followed this requirement, others reported on a smaller selection of EU languages, non-EU languages, or simply provided top-level numbers. Some platforms provided helpful context on their approach to content moderation more broadly, calling out the complexity of maintaining a multilingual staff, often working on multilingual countries, with some focusing on important content moderation functions that are language agnostic.

Overall, we learned somewhat unsurprisingly that English speakers made up the highest number of moderators in the six companies we examined, followed by German and French speakers. In some companies, we saw some languages covered by no staff (eg. Danish on X and LinkedIn), or as few as one or two staff members (e.g. Maltese and Irish on TikTok). When comparing these numbers to the countries with the highest monthly active users, it doesn’t always align. For example, Meta reports higher usage in Italy than Germany, but the platform has an overrepresentation of German moderators even when accounting for Austria.

In looking at each of the six platforms’ approaches to reporting, we found that Google, Meta (including Facebook and Instagram), and TikTok reported against the required list of EU member state languages. All three also acknowledged that some EU-based moderators work on moderation that is language agnostic, such as those who may work on nudity, spam, and photo analysis. Both Meta and TikTok also contextualized their figures by noting that moderators outside of the EU contribute to linguistic expertise in member state languages spoken in other parts of the world, such as English, Spanish, and Portuguese. TikTok and Facebook also noted moderators within the EU focus on nonmember-state languages, with TikTok calling out Turkish and Arabic as examples.

Google reported numbers for “human resources evaluating content” in all 24 languages across five of its products: Maps, Play, Shopping, “Multiservices” (content that appeared across multiple google services), and YouTube. The company stated that “identifying the human resources who evaluate content across Google services is a highly complex process” and that its language breakdown “should not be aggregated as this may not reflect the total number of unique content moderators available to conduct reviews.” It utilized different methods of aggregating these metrics across its multiple services, and also noted the challenges of providing metrics when employing staff with multiple linguistic capacities. Google reported on staff with nonmember-state language skills who had moderated languages that are unique to Europe (Breton, Basque, Occitan, Catalan, or Corsican) using a category titled “Unknown.” The company also used this category to include staff moderating content found using multiple languages, or “where there are limitations in reporting the content language.” It is not clear what Google is referring to in this last category. Google also published figures on staff working on language-agnostic moderation under an “Agnostic” category. Notably, YouTube was the only service that did not have figures in the “Unknown” and “Agnostic” categories.

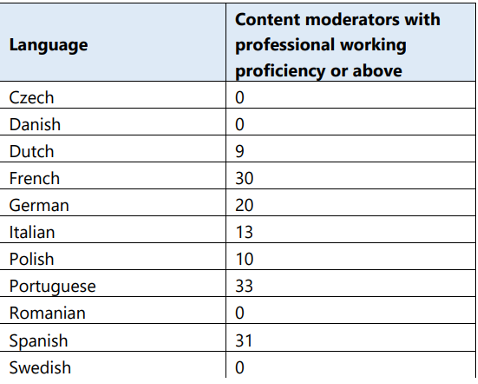

X, formerly Twitter, is perhaps the greatest outlier, both in terms of its lack of staff and comprehensive reporting. X stated that it has 2,294 staff on its global content moderation team, and that its teams “are not specifically designated to only work on EU matters.” Instead of reporting against member states’ official languages, the company reported on “people in our content moderation team who possess professional proficiency in the most commonly spoken languages in the EU on our platform.”

X reported on moderators with “proficiency” in thirteen languages, eleven of which are EU official languages. As a result, X lists moderators with Arabic and Hebrew language skills but not, for example, Greek or Swedish, leaving many to ask whether X assessed Hebrew and Arabic to be highly spoken languages in the EU, or were just reporting on a single individual’s multiple language skills. X also stated that it had 2,294 English speaking moderators on its overall team, matching its total number of reported moderators.

LinkedIn reported on eleven of the official EU languages (interestingly leaving English, an EU official language, off their list). The company stated it had omitted the other thirteen languages because its “website is currently available in and supports 12 of the 24 official languages of the EU,” implicitly referencing its English capacity without reporting on it officially.

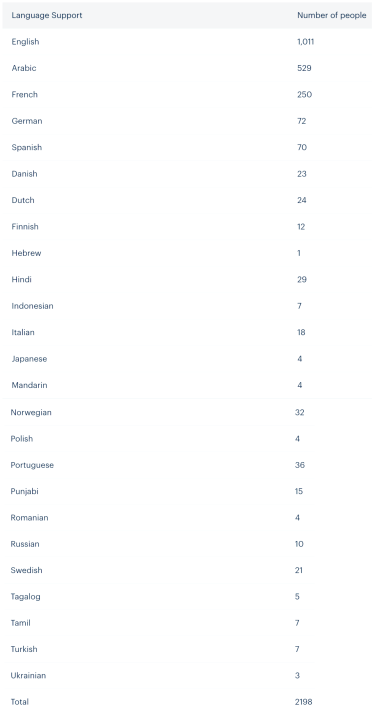

Snapchat included its EU mandated transparency report as part of a larger report on global operations for the company. In it, there is a single webpage on which it states multiple times that it is “where we publish EU-specific information required by the EU Digital Services Act (DSA).” On that page, Snapchat includes two untitled charts. In the one that appears to be its reporting on language capacity, it only lists “language support” at the top, with 24 languages listed below, including twelve of the required 24 EU languages alongside Hebrew, Arabic, Indonesian, Hindi, Japanese, and others. Snapchat does not clarify exactly the functions played by those individuals at the company with such language skills, nor does it mention content moderation anywhere on the page.

What comes next

Article 42 requires VLOPs to publish transparency reporting every six months, so we will see the next round of reports in late April/early May 2024. DSA implementation is an iterative process so we can expect what researchers, policymakers, and regulators raise as useful, lacking, or insightful from this first set of reports to inform what companies choose to track and disclose and what the European Commission clarifies in future requirements.

It will be interesting to see the European Commission’s reaction to companies like X, which clearly sidestepped DSA requirements around reporting. Will the Commission tie the information to ongoing investigations, launch new ones, or settle on outright fines? What space or support will companies be given to remedy issues? Perhaps more interestingly, how will the EC interpret submissions like LinkedIn’s, which seemingly faithfully reported on its language coverage, but showed a lack of expected capacity. How might this transparency report impact the Commission’s reception of the company’s risk assessment and any eventual mitigation steps?

For a company like Meta, which reports on all required languages, will the company’s approach to multilingual content moderation be viewed as sufficient? Or will the information be leveraged to study which platform approaches best mitigate risk and set new standards? The EU’s response to each of these questions will set a precedent for future reports and undoubtedly impact platforms’ proactive approaches.

The most important part of these transparency disclosures is that they can help governments and civil society ask better questions to take steps to accountability, and companies better benchmark against industry standards. They open up an avenue to understand what is happening in the digital sphere, through which better policy can be crafted. In this way, they are a means to accountability, not an end in themselves. They will inform other components of the DSA, such as risk assessments, audits, and other reporting requirements, and enable us to better measure the impact of various interventions. Transparency is a building block to the rest, and this round of reports is our first look “under the hood” of these companies.

We should also consider new questions spurred by these disclosures. For example, X and Snapchat’s reporting on Hebrew and Arabic language moderators further exemplifies the global nature of the internet. While Europe requires companies to report on European language capacity, it’s certainly useful to know what moderation capacities exist for parts of the world mired in a violent conflict, viewed online and discussed in every corner the globe.

This piece only looks at the number of staff capable of moderating specific languages; content moderation and platform policies entail far more than just that, of course. But this one element can be used as an example of how to engage with these reports and the value they may present more broadly as future ones are released. These reports also give us a sense of how platforms approach languages with fewer speakers and can help focus the asks and approaches of those working to improve how companies operate in a range of countries outside of Europe and around the world.

Civil society groups have been advocating for years to see information just like this. Thanks to the DSA, we now have a starting point for asking more questions, better understanding the information ecosystem, developing positive innovations, and crafting more effective rules.

Cite this case study:

Konstantinos Komaitis, Jacqueline Malaret, and Rose Jackson, “Learning more about platforms from the first Digital Services Act transparency disclosures,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), December 6, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/12/06/learning-more-about-platforms-from-the-first-digital-services-act-transparency-disclosures.