How Palestinian militants use Telegram videos in the Mideast conflict

Palestinian militant factions appear to be operating with a high degree of technical coordination, producing uniformly branded propaganda videos with regularity.

BANNER: An Ezzedeen Al-Qassam Brigades (EQB) propaganda poster featured on Telegram. (Source: EQB)

Much has been written about the use of technology in the current round of fighting between Israeli and Palestinian forces in the Gaza Strip. From cyber warfare, artificial intelligence, circumventing communications blackouts, and the use of new defense technologies, there is much to look at. While much of this has focused on advancements made by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), Hamas’s armed wing, the Ezzedeen Al-Qassam Brigades (EQB), has also displayed a variety of weapons, some new, as prestige symbols. These include engine-powered paragliders, anti-tank rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) (Al-Yassin), torpedoes (Al-Asef), suicide drones (Al-Zouari), explosives dropped from drones, hand-held explosive devices (Commando Action Packages), and surface-to-air anti-aircraft projectiles (Mutabar 1). Many of these technologies feature heavily in the group’s early propaganda efforts.

In the current fighting, some videos were created especially to showcase these technologies, with especially high production value used to announce the deployment of new weaponry and associated tactics.

This case study will focus on a different aspect of the technological production efforts of Gaza-based Palestinian militants, namely, the use of video as a propaganda tool. Our analysis will center on the technical, functional, and aesthetic qualities of these videos.

Methodology

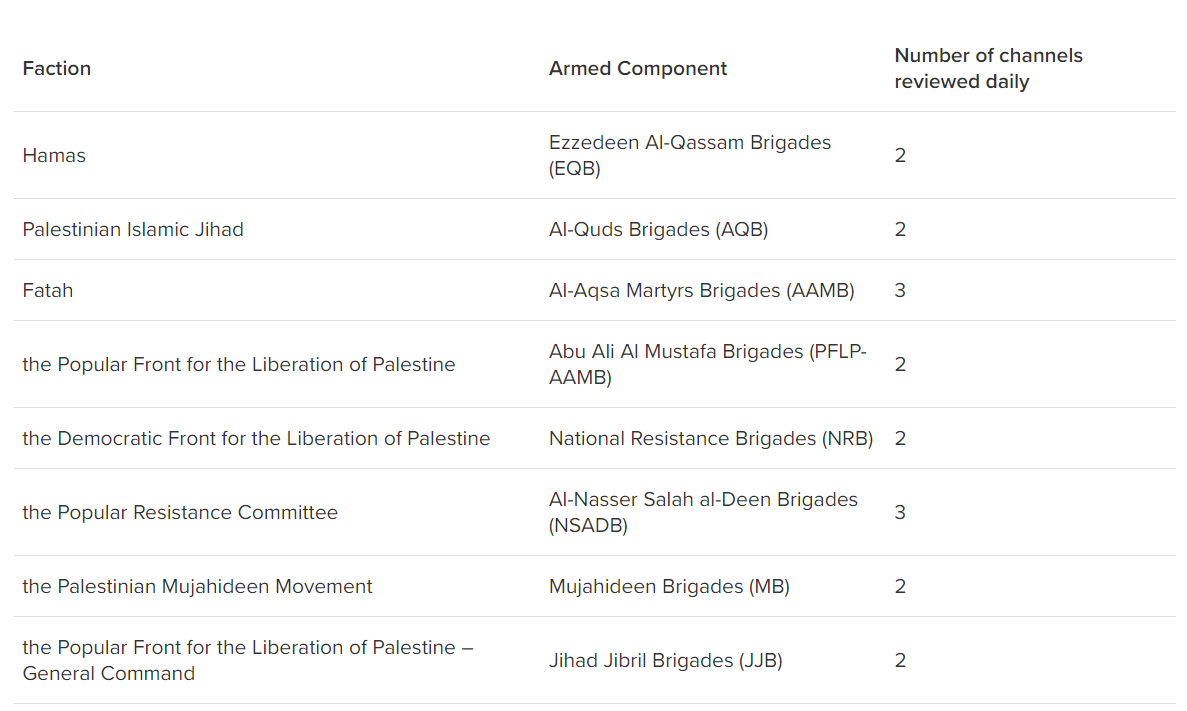

The analytical underpinning for this project can be found in content analysis methodologies, developed by such scholars as Klaus Krippendorff, Kimberly Neuendorf, and Johnny Saldaña, and informed thematically by Jonathan Matusitz and Thomas Hegghammer. Videos were collected daily from eighteen Telegram channels, which serve as official (and quasi-official) communication hubs for Palestinian factions. To ensure the inclusion of only official, branded releases videos were collected directly from the eight factions’ Telegram channels. This involved daily scans of channels belonging to each faction.

After a daily scan of these eighteen feeds, nine unofficial aggregator channels were reviewed to ensure no videos were missed. Finally, peripheral video content was reviewed, such as videos produced by the IDF, Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthis, and Palestinian armed groups operating in the West Bank. For example, a series of videos was produced by AAMB in Jenin, Nablus, and Tulkarem, with fighters acting in support of EQB and AQB’s “Al-Aqsa Flood” operation. EQB also released a West Bank attack video showing a drive-by shooting in Beit Lid, but this was excluded from the analysis, which is focused entirely on Gaza. These non-Gaza videos were reviewed, downloaded, and categorized but not coded.

Speeches by organizational spokespersons, such as releases showcasing Hamas’s Abu Obeida and Palestinian Islamic Jihad’s (PIJ) Abu Hamza, were collected but ultimately excluded.

All unofficial and unbranded videos were excluded, as were social media posts distributed by but not produced by the organizations, for example, TikToks created by Gaza residents and distributed by an official Hamas channel.

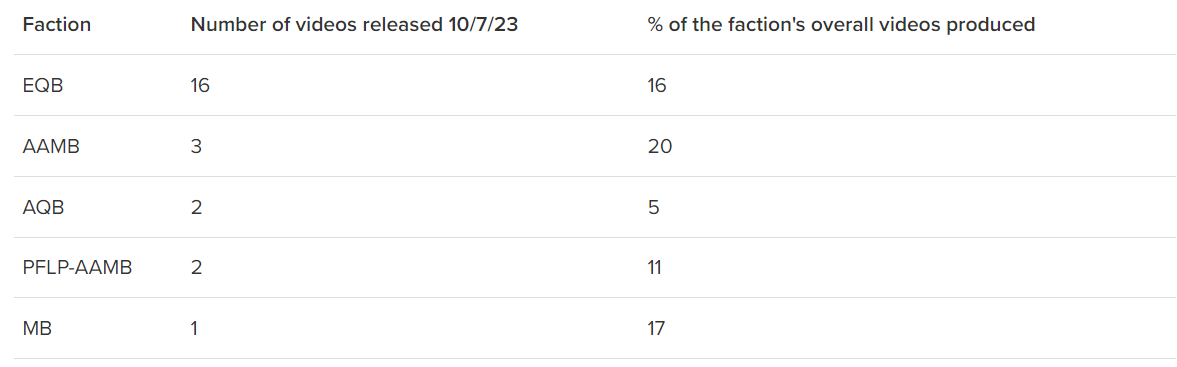

This study is inclusive of videos released in the first six weeks of the war—October 7 to November 18, 2023. Based on this methodology, 405 videos were collected, after exclusions, the video corpus consisted of 192 official, non-spokesperson, Gaza-based videos within the date range, spanning more than 299 minutes (nearly five hours) suitable for analysis.

Coding occurred by hand, using a fifteen-variable iterative codebook. Test cases were selected at random to develop the initial variables and values, and after systematic review, were modified before finalizing the framework. This process yielded fifteen variable fields inclusive of ninety-seven possible values.

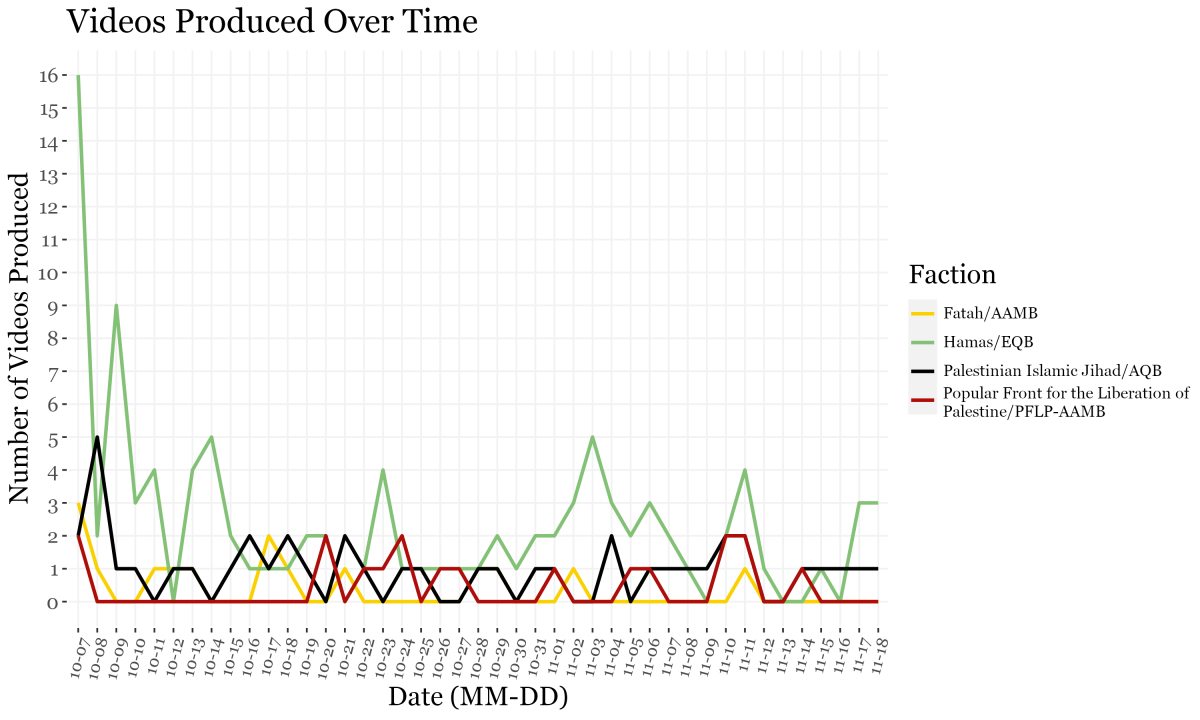

Cross-faction trends

There are several notable trends when inspecting the video corpus irrespective of faction. First, the focus of the videos—as observed through three variables: video type, target of attack, and featured weapon—changes over time in lockstep with the conflict itself. Videos produced in the days immediately after October 7 heavily focus on attacking IDF military infrastructure and armored forces, and hostage-taking. These early videos were more likely to integrate cellphone video (not exclusively content recorded on head-mounted/GoPro-type cameras) and to be released without standardized introductory title screens, music, or graphical effects. Many of the videos released on October 7 had lower production values, suggesting they were hastily prepared to capitalize on the surprise nature of the offensive.

Within a couple of days following the initial offensive, videos shifted to more persistent guerilla warfare tactics, often with ranged weapons such as rockets, mortars, and drones. By the end of October, Palestinian factions returned to mobile, conventional attacks targeting IDF ground forces, with a renewed focus of video releases showcasing military capabilities such as new weaponry. This three-stage account—initial attack, guerilla persistence, conventional counter-offensive—mirrors the fighting on the ground and provides further insight into the Palestinian military strategy.

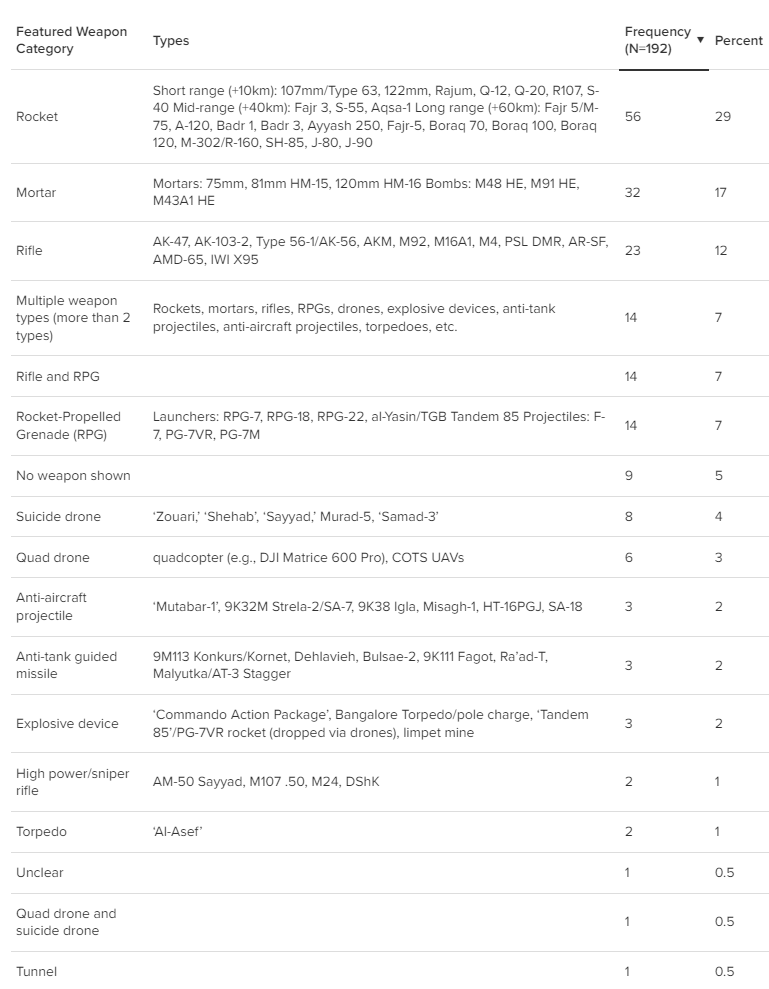

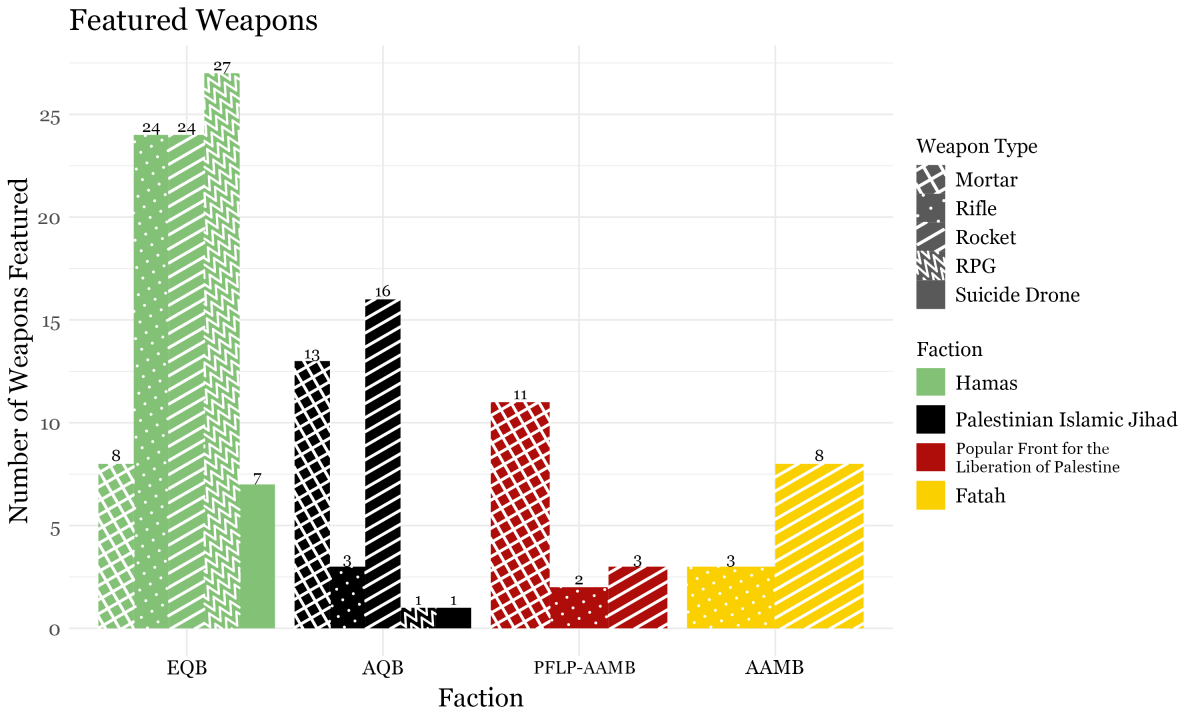

Most videos focus on a single weapon type. Seen across factions, several weapon types are prominently featured.

While 92 percent of videos feature only one weapon type, videos of an explicitly threatening nature tend to show a wide variety of weaponry—assumingly to communicate military prowess and thus an increasingly threatening opponent. These threat videos (3 percent of all videos) feature either a variety of weaponry, or the use of long-range, sniper rifles and tunnel warfare to intimidate ground forces.

Audience

While some may presume that the audience for propaganda videos is explicitly in-group or out-group communities, there is little evidence on the production side. In seeking to identify videos meant to speak to Israelis, the DFRLab looked for the presence of Hebrew text, translations between Arabic and Hebrew, and/or video titles written to be threatening—to ‘speak’ to ground forces or the wider Israeli populace. Videos with threatening titles include:

- Our commandoes are waiting for you (AAMB, 10/27/23)

- We are waiting for you (AQB, 10/19/23)

- Hell awaits you/Welcome to hell (AQB, 10/21/23)

- You will be defeated (NSADB, 10/26/23)

- This is what awaits you when you enter Gaza (EQB, 10/14/23)

- Your heads will be crushed (PFLP-AAMB, 11/10/23)

These videos are a mix of scripted, high production value content and battle footage meant to show the military capabilities of the Palestinian fighters and to inspire fear in the IDF’s ranks—fear of capture, and fear of injury or death. The other videos coded as threatening feature Israeli captives’ directing critical words at the Israeli leadership of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

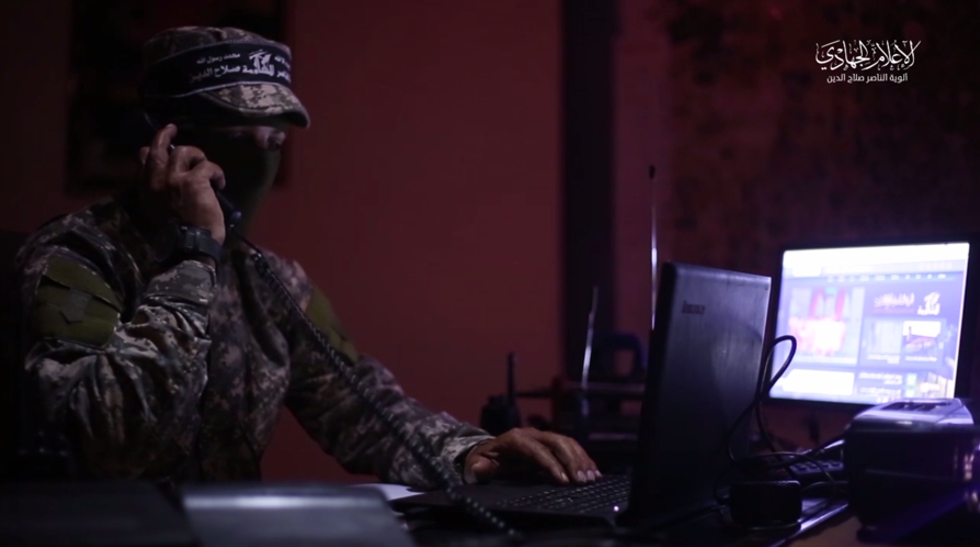

On rocket-mortar launching videos

Amongst the factions, some show sophisticated videography craftsmanship. For its part, AQB appears to put greater emphasis on the persuasive power of dramatic video, with nearly half (48 percent) of its forty-two videos utilizing scripted, high production value content, and 67 percent adopting dramatic music. These scripted videos utilize high-definition video, multiple cameras capturing multiple angles, purposeful lighting, set design, and costuming, and because of their careful orchestration, often show militants masked but not digitally obfuscated. These scripted portrayals often show militants manufacturing weaponry, and training for or coordinating complex attacks.

These high production value video portions are typically set to dramatic, patriotic, instrumental music, and show uniformed fighters in highly sophisticated, clandestine command and control facilities. Masked and uniformed fighters are shown preparing rockets, traveling in tunnels, and planning attacks in complex operational centers.

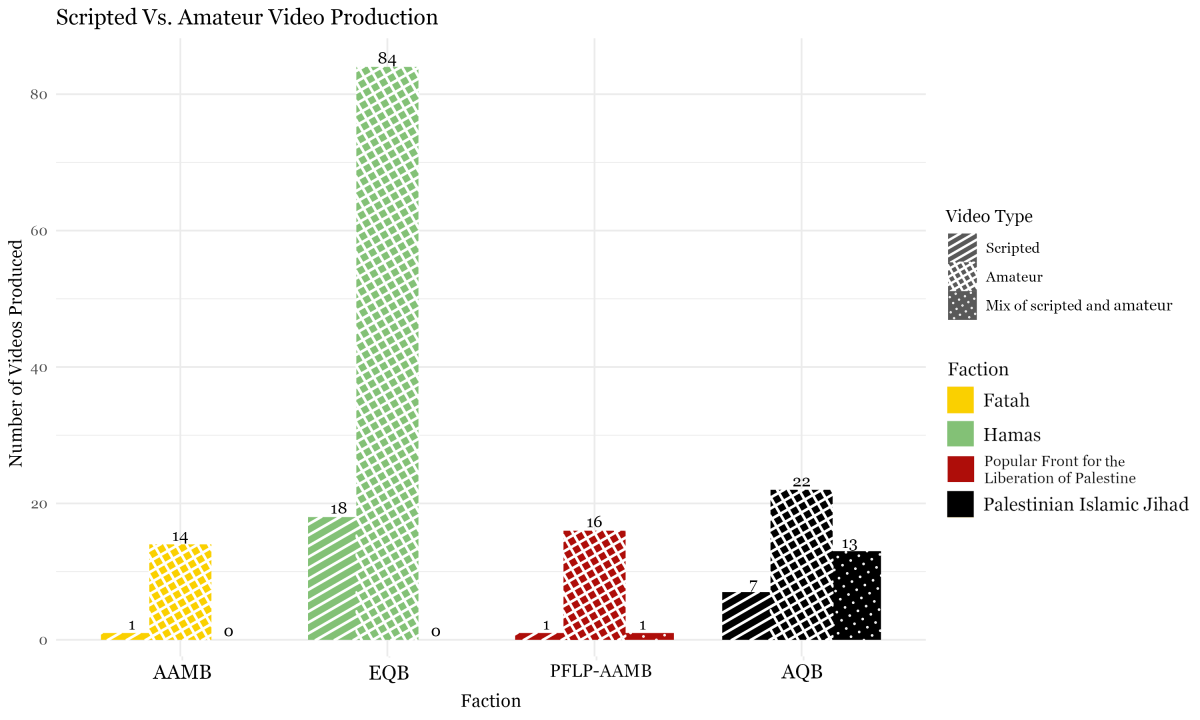

AQB distinguishes itself as the only faction with scripted, high production value content and added dramatics integrated into their rocketry and mortar videos, while EQB, AAMB, PFLP-AAMB, and JJB’s releases are often drab and formulaic. These AQB-scripted videos stand in stark contrast to PFLP-AAMB’s highly formulaic releases lacking high production value. Video production for PFLP-AAMB appears to be of a less central focus, as the group produced a few videos on October 7, and then went silent for nearly two weeks, until additional releases were published October 20.

Excluding those of AQB and NSADB, most factions’ launch videos utilize amateur video, ambient recorded sound, obfuscated landscapes and people, and fail to show the point of impact. As one of the most recurrent video types, and most frequently featured weapons, rockets and mortars feature prominently in all factions’ releases.

Projectile impacts

Throughout the entirety of the rocket-mortar launching genre, video makers fail to exhibit the point of impact. While videos’ naming conventions can help—”Intense missile barrage towards Tel Aviv” or “Bombarding Eilat with an Ayyash 250 missile”—the impact and destruction is ominously left as an implied, assumed reality for the viewer. While the video producers could readily retrieve and intermix impact video shared on social media, this does not occur, and the viewer is left with the impression that many, if not all, of the projectiles reached a target. One departure from this trend is an October 24 AQB video, which shows a series of mortar launches and their purported impact points. The video’s producer(s) claim the mortars struck all military targets—parked Merkava tanks, tanks en route, an “armored corps company,” and an “armored personnel company.”

In previous conflicts, the vast majority of long-range rockets fired toward Israel were neutralized by the Israeli Iron Dome system. In the current conflict, according to the IDF, 10 percent of rockets fired have fallen in Gaza. On November 9, another anti-missile defense systems, the Arrow-3, had its first successful combat interception, countering an EQB-fired Ayyash 250 surface-to-surface rocket.

Technical-visual elements

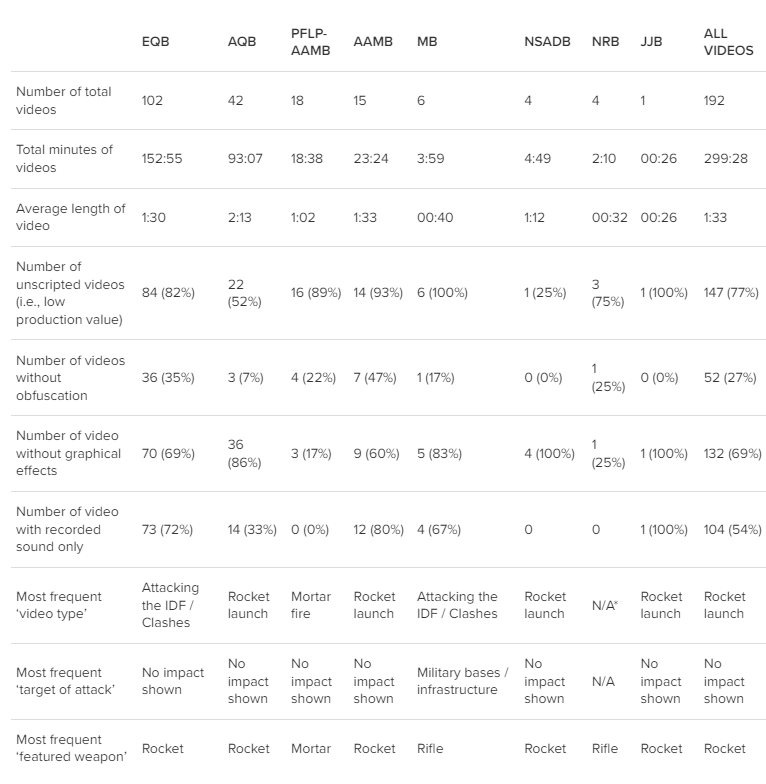

Throughout the conflict, EQB produced far more videos than any other faction—more than half (53 percent) of all video releases and more than half (51 percent) of all minutes recorded.

EQB has experimented with a variety of video formats over the years throughout a series of military engagements, with this recent conflict, it has further professionalized video production and brand management. In part this has been due to increasing standardization in their production cycle (e.g., templated title sequences), providing a cleaner, more professionalized feel. This move is a further shift away from the martyrdom videos that dominated the Al Aqsa Intifada (2000-2005). Throughout the current conflict, some EQB videos featured a plain, less-stylized black template with white-orange text. These were quickly replaced with a more visually appealing style in subsequent releases.

This black title screen is seen in six EQB videos (6 percent of their total releases), but only those released on October 7. Interestingly, this first-generation black template is very similar to other factions’ title sequences.

Notably, five factions’ use of the black template adopts white and yellow-orange text.

In subsequent releases, most factions deployed a second-generation template wherein greater brand alignment can be seen. For EQB, this is first showcased in four of their sixteen releases dated October 7.

Part one of the new design features the classic EQB figure of a caricature-styled fighter holding an M-16 and Qur’an, dressed in a keffiyeh, holding a shahada flag. This green template was observed in 73 percent of EQB’s releases. AQB, the second-highest producer of videos, uses a standardized title screen with greater uniformity, adopting a green background centering a triangle that vignettes a scene from the video throughout 95 percent of its videos.

This initial image is then replaced by a second informational slide providing context for the video.

This second informational title sequence is consistent amongst all factions, displaying relevant information (e.g., date, location, description). For AQB, all but two of their videos matched this stylization. Many factions also utilize standardized formats for the ending of videos.

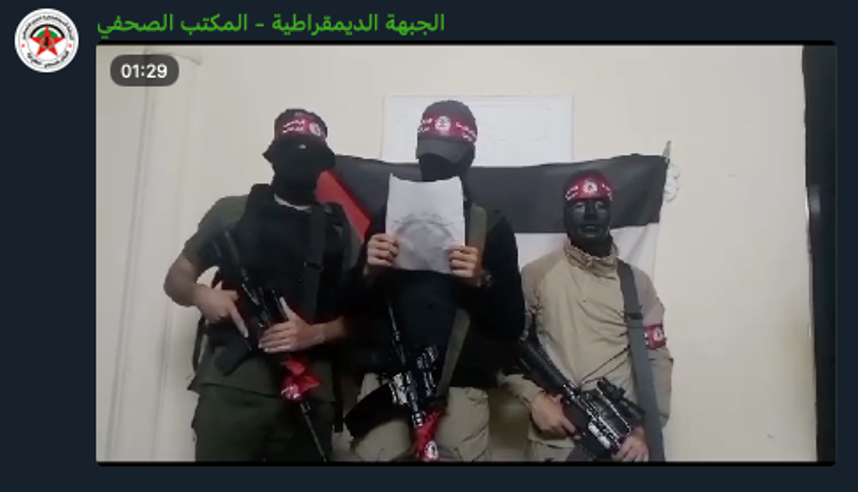

Other factions show similar adaptations and changes in their stylization. Although the sample is smaller, AAMB utilized several title sequences, such as the “silhouetted gunmen” template seen below and utilized in 53 percent of their releases.

Nearly all the factions surveyed showed some manner of progressive production adaptation, such as PFLP-AAMB adopting a heavily animated introductory title sequence after several videos that utilized a plain black template.

Post-production effects

Beyond brand alignment and standardization, many factions routinely deploy the use of post-production graphical effects to increase their operational security (e.g., redacting faces) and increase the legibility of often chaotic battle footage (e.g., adding target markers).

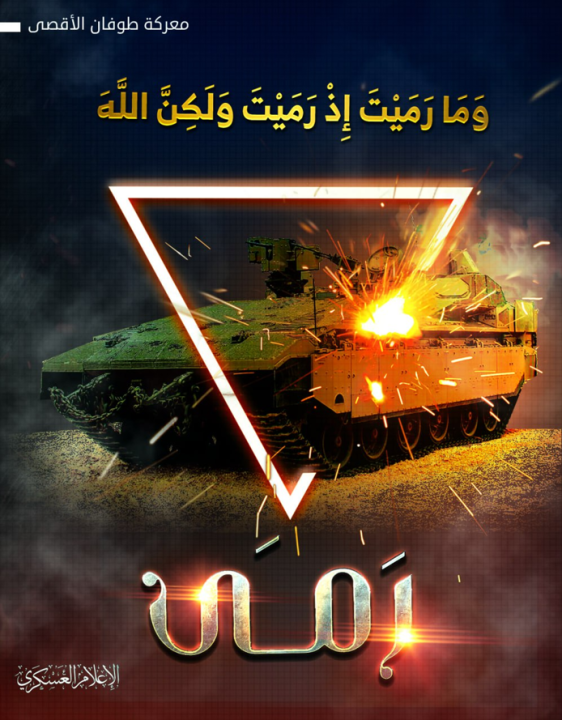

In examining these graphical additions, none are more utilized in the current round of fighting than EQB’s use of inverted red triangles to mark targets. This method was present in 24 percent of EQB’s videos (11 percent of videos overall), and was unveiled in a video documenting an October 29 attack on an IDF armored personnel carrier, which reportedly resulted in numerous IDF fatalities.

The use of this marking, new in the current upheaval, has quickly become iconic following scenes of fighters placing explosive devices directly on tanks (i.e., zero range), and barefooted militants ambushing armored forces with homemade RPGs. While it is unclear if EQB intended for this to be a persistent element in its visual brand, the group and its allies have begun producing propaganda posters utilizing the image, further capitalizing on its brand recognition.

Overall, the Gaza-based Palestinian military factions appear to be operating with a high degree of technical coordination, producing uniformly branded videos with regularity, and high production value. The use of standardized title and closing sequences, music, obfuscation, and proprietary visual markers, speak to a maturing production cycle—a leap forward from grainy, irregularly-formatted martyrdom wills and combat shorts that dominated the second intifada and the years that followed.

Sound and sight

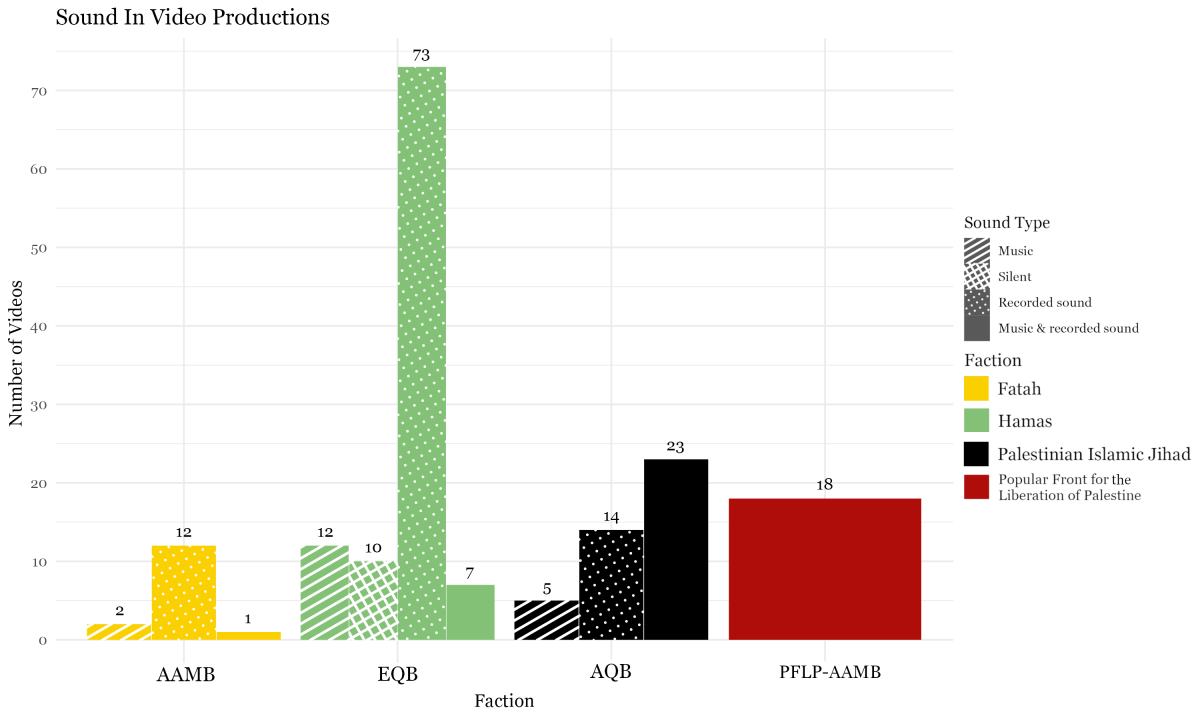

The use of sound reflects brand management methods, as factions show a high degree of alignment in such practices. Overall, 83 percent of releases utilize recorded, ambient sound—the whizz of rockets launching, the thud of mortars firing, etc. Fifty-four percent utilize only naturally recorded sound, while thirty-nine percent use some manner of recorded music. Interestingly, 7 percent of videos are silent.

When viewed by faction, EQB relies on recorded sound in 78 percent of videos, and AQB 88 percent. When looking at videos that use only music (i.e., highly scripted videos), we see this in only 12 percent of EQB releases and 12 percent of AQB releases. These findings show that the two most frequent video producers rely largely on naturally recorded soundtracks and reserve musically driven releases for occasional, high-production value releases, often focused on exhibiting military might and directly threatening IDF forces. Another notable finding is that nearly none of the factions or their releases rely on narrators—a more common trend in previous eras of Palestinian videos. For the Gazan militant factions, only 4 percent of videos involved narration.

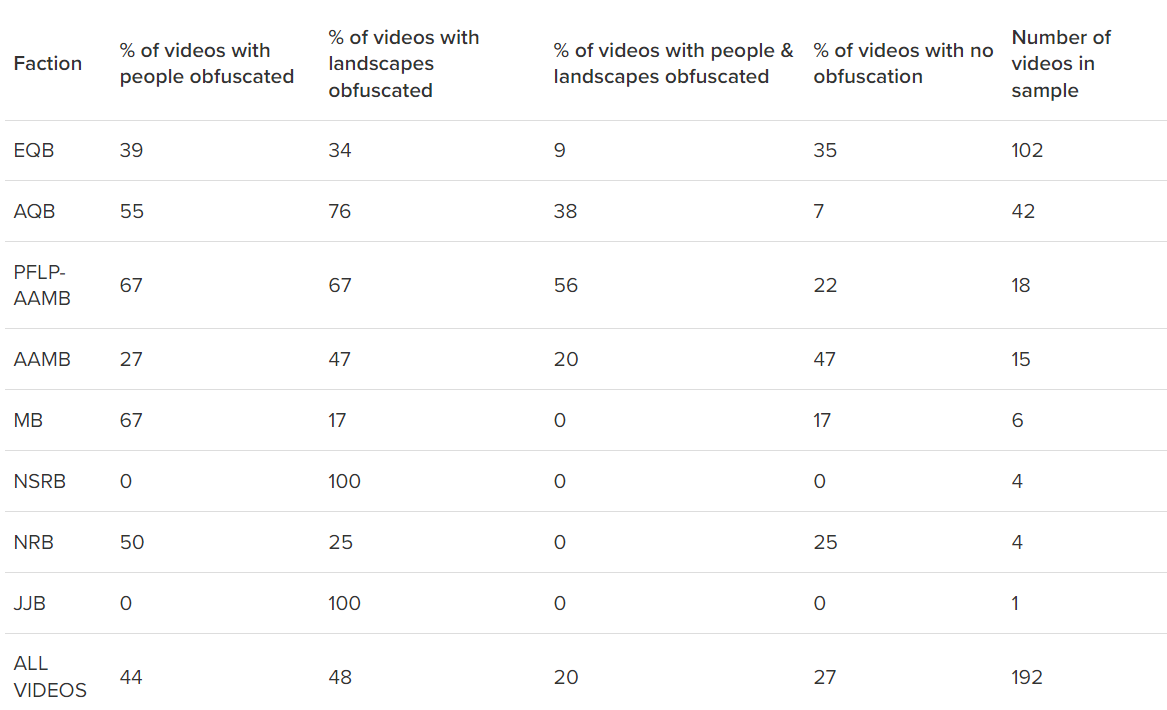

One notable feature, seen often in mortar and rocket launch videos, is the blurring of fighters’ faces, and the obfuscation of landscape markers to impede visual analysis-based geolocation.

For example, by obscuring a tree line or nearby building, fighters are attempting to stymie Israeli attempts to pinpoint launch sites through common methods of geospatial analysis. While fighters often wear masks, and launch sites are often concealed under tarps or other barriers, the use of post-production digital obfuscation is still common amongst the factions.

This breakdown shows the diversity of practices utilized by the factions. Some of this is driven by video type, for example, 94 percent of EQB’s thirty-six launching videos (i.e., rockets, mortars, suicide drones) utilize obfuscation, well above the cross-faction average. Due to the prominence of rocket and mortar launching videos across factions, it is no surprise that landscape obfuscation is the most common form of concealment. Although digital obfuscation of people is not very common in the larger collections, fighters are nearly always shown with their faces covered by a mask or balaclava.

Overall, PFLP-AAMB’s videos stand in contrast to those of EQB and AQB in terms of standardization and simplicity. The PFLP-AAMB videos are short, utilize the same patriotic music, and rarely vary in format. Nearly every PFLP-AAMB video analyzed was identical concerning the variables examined, with uniformity no other faction showed. EQB and AQB on the other hand adopt a mix of sound types, visual markers, video lengths and other factors to create a far more diverse and dynamic video catalog.

Video production speeds

It is often unclear when a particular event portrayed in a video occurred, but due to the atypical nature of the October 7 attacks and the fighting that followed, we have clues about the production lifecycle. The clearest example comes from an AQB video published November 12. In this video, a fighter launching a mortar displays a handwritten sign.

Taken at face value, this would indicate a two-day turnaround time between the recorded action and the video’s release.

A second notable example was published by EQB and shows the boobytrapping of a tunnel shaft in Beit Hanoun—an attack that killed five IDF soldiers. The video was published November 16, but the date included in the video’s introduction reads November 11—the day the deaths occurred. Therefore, it took EQB five days to publish. A third incident—an EQB shooting in Beit Lid, West Bank—which occurred November 2, was the subject of a video released November 11, nine days after. While this non-Gaza video was excluded from the present analysis, its production timeline is the longest and provides an additional data point.

This limited data suggesting a 2 to 9-day production cycle (5-day average) is notable given the conditions of war on the ground. While varied, rapid production of these materials appears within the means of most factions. On October 7, at least twenty-four videos were swiftly published showing attacks on civilian sites in Nahal Oz and Be’eri, and military sites in Re’im, Erez, Kfar Azza, Zikim, Kissufim and areas north and east of the Gaza Strip.

Summary of findings

A great deal of operational and aspirational logic can be deduced by the preceding analysis. How factions conceive of and implement brand management, messaging strategies, security practices, and other areas of concern appears to vary widely by faction, video type, and its implied intent. Further analysis is warranted with a larger data set, especially key for those factions with few releases.

At present, we can conclude with confidence some notable data points:

- EQB, PFLP-AAMB, AAMB, MB, NRB, and JJB rely on lower production value, amateur videos far more than AQB and NSADB.

- AQB and NSADB utilize high production value video, both by itself and in conjunction with amateur video, most often.

- EQB and AAMB are the only factions less likely to obfuscate their fighters or their locations when compared to the overall average.

- The smaller factions with fewer video releases appear to have less sophistication in their productions, showcasing less graphical effects and less emphasis on production value.

-However, factions with few releases issue frequent text statements recounting their role in ground fighting, and thus video releases may not be an accurate reflection of roles and activity on the ground. For example, NRB issued more than 80 communiques between October 7 and November 25. NSADB and MB each issued more than 50 text-based communiques.

-Across factions, the most frequent video type is typically a launch—either of rockets or mortars—or more generally, a video showing factions’ attacks on Israeli military forces. Correspondingly, most factions’ featured weapons are rockets.

These and other cross-faction comparisons can be seen below.

*No trend shown due to even distribution and limited sample size

Conclusion

It is often said that terrorism—no matter how analytically flexible and value-laden the term is—is a process of communication. The production of videos is certainly an integral part of that communications ecosystem. These cultural products help groups competing for finite constituencies differentiate themselves and promote their individualized aesthetics of resistance. In conjunction with audio speeches, music, flyers, photographs, memes, political and military statements, and a growing variety of other ephemera, the increasing sophistication and instantaneous distribution of branded material via platforms such as Telegram make these artifacts a vibrant and fitting subject for study.

Brand management amongst Gaza’s military factions seems to guide video production practices in conjunction with practical concerns such as operational security, and reasonable expectations of what fighters can capture while engaged in battle. As the nature of the battle on the ground changes, so too will the videos. At the time of editing, the conflict is in a post-ceasefire period, following a seven-day pause in hostilities—a negotiated temporary humanitarian respite (November 24-30), which ended December 1. It is possible that this temporary reprieve and the period that follows will influence the production cycle of video propaganda. While a halt-then-return to hostilities may provide factions needed time to regroup—collecting footage from field operatives, distributing equipment to additional teams, editing video received for release—it may also lead to a slowing in video production as source material dries up temporarily.

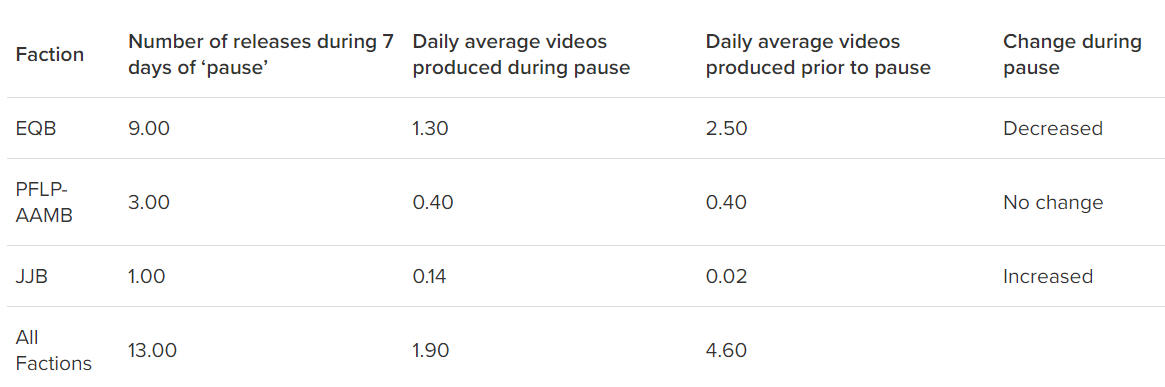

Preliminary analysis indicates that video production is slowing during the period of calm while both Israel and the militants focus on an exchange of captives and prisoners. Since the pause began on November 24, daily video production has slowed throughout the factions overall.

Before the pause in fighting, factions averaged more than four-and-a-half videos per day. Across the eight factions, November 24-30, only thirteen videos were released at a rate of 1.9 per day. Thus, during the pause, factions’ production slowed overall—nearly a half speed.

December 1, the day the calm ended and ground fighting resumed, AQB, EQB, and PLFP-AAMB released videos, followed the day after by the NRB, AAMB, and additional releases from PFLP-AAMB, EQB, and NRB. Within two days of the resumption of fighting, five of the eight factions—EQB, AQB, AAMB, PFLP-AAMB, NRB had published videos of rocket launches, mortar fire, launching suicide drones, ground fighting, and downing and Israeli drone.

Subsequent studies will seek to extend this analysis in the second month of hostilities to determine how these trends sustain or change over time.

Michael Loadenthal is a contributing writer to the DFRLab. He is an Assistant Research Professor at the School for Public and International Affairs at the University of Cincinnati, focusing on political violence, threat modeling, and security practices within extremist networks.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Carter Langham, an undergraduate student at Regis University and Associate Data Scientist with the Prosecution Project, for assistance in producing the data visualizations used throughout. Additional thanks to a college, who preferred to be unnamed, who provided secondary review to discussions of military hardware.

Cite this case study:

Michael Loadenthal, “How Palestinian militants use Telegram videos in the Mideast conflict,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), December 12, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/12/12/how-palestinian-militants-use-telegram-videos-in-the-mideast-conflict.