How foreign actors targeted Polish information environment ahead of parliamentary elections

Foreign – or seemingly foreign – actors implemented different interference actions in order to influence Polish voters or foment societal instability

How foreign actors targeted Polish information environment ahead of parliamentary elections

Share this story

THE FOCUS

BANNER: Krakow, Poland – October 15: Voting at a polling station during the parliamentary elections on October 15, 2023 in Krakow. Poland. Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on October 15. The elections were accompanied by a highly controversial referendum during which four questions were asked, including about migration policy. (Source: Klaudia Radecka/NurPhoto via Reuters)

This report was produced as part of the international election monitoring project of the Polish Election Watch network, implemented by Alliance4Europe, OKO.press, and the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab).

Ahead of the October 15, 2023, parliamentary elections in Poland, seemingly Russian and Belarusian actors attempted to influence Polish voters by utilizing different influence techniques, including phishing and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against Polish targets, amplifying disinformation, fomenting instability by targeting divisive issues within Polish society, and disseminating fabricated content to undermine trust in Polish institutions and elections.

Poland has entered a long election cycle: the October 15 parliamentary elections will be followed by regional elections in 2024 and presidential elections in 2025. Against a background of particularly urgent current events, in particular Russia’s invasion of Poland’s neighbor Ukraine and the protracted migrant crisis on the country’s border with Belarus, foreign – or seemingly foreign – actors targeted the Polish information space with hostile influence operations. Given their potential outsize impact if a more amenable politician wins or domestic instability escalates, elections are highly targeted political events by foreign actors, as many European countries have experienced. Such operations are often designed to undermine public trust in democratic processes in the societies of geopolitical adversaries. Due to the Polish government’s support for Ukraine in its defense from Russian aggression and the ongoing confrontation with Belarus, the October parliamentary elections attracted seemingly Russian and Belarusian threat actors attempting to meddle in Polish elections.

This report relies on election interference framework, as developed by the Atlantic Council based on the analysis of foreign meddling in elections or referendums held between 2014 and 2018 in five European countries. The framework outlines six different types of “interference actions,” namely “infrastructure exploitation, vote manipulation, strategic publication, false-front engagement, sentiment amplification, and fabricated content.” The DFRLab’s analysis showed that foreign actors newly carried out four of the six different types of interference actions – infrastructure exploitation, false-front engagement, sentiment amplification, and fabricated content – against Poland in the lead up to the October parliamentary elections. The DFRLab also found one of the main political parties in Poland electioneering by resurfacing older hack-and-release materials, which would fall under the Atlantic Council’s interference action of strategic publication, but did not find any evidence of the final category of action, vote manipulation.

Infrastructure exploitation

The first interference action in the Atlantic Council’s framework is infrastructure exploitation, which entails actions such as “reconnaissance and collection efforts that gather or distort data or functionality of information technology (IT) systems or networks.” Such actions can be undertaken as part of cyber espionage operations, when hostile actors illegally penetrate into a target system to steal sensitive information or disrupt the proper functioning of a network. Russian and Belarusian threat actors conducted at least one phishing attack and multiple DDoS attacks against Polish targets in August and September 2023.

According to the Polish government’s Plenipotentiary for Cybersecurity, hacker group UNC1151 (more commonly known by its nom de guerre, Ghostwriter), which is “probably linked to the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (GRU),” conducted a phishing attack on August 22, impersonated two high-level officials from the Polish government, and sent emails containing Cobalt Strike malware to members of the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS). On the last, the government’s press release stated that, once installed on a victim’s computer, Cobalt Strike can allow hostile actors “to steal data, demand ransom, or send malicious messages to subsequent recipients.” The press release further stated that, upon request from CERT Poland experts, email service provider “immediately blocked suspicious mailboxes to limit the spread of malware,” thus it is unclear to what extent this particular operation was successful. The press release also mentioned that Poland’s then-Minister of Digital Affairs Janusz Cieszyński had briefed representatives of the Law and Justice Electoral Commission about the attack, because both impersonated individuals as well as the recipients of infected emails were PiS members or supporters.

In a separate incident, in August and September 2023, over fifteen Russian hacker groups carried out a series of DDoS attacks against Polish websites. On September 4, the central hacker group behind these attacks, NoName057(16), provided additional details about the broader context of the attacks on its Telegram channel, which revealed that the DDoS attacks were connected to the elections. A post in Russian to NoName057(16)’s Telegram channel started with a sentence: “elections are coming in Poland…” and that Russophobia is an “ideology of the current government,” while the statements and activities of PiS’s main opponent, Civic Platform candidate Donald Tusk, “are filled with sick ambitions…” The post also claimed that, unless young Poles “change” (i.e., through elections) the “anti-Russian ideology in Poland,” the country would continue to become “poorer every day.” The last sentence of the post claimed that, “while the young Poles are ‘maturing,’ we say DDoS hello to Poland.” According to other Telegram posts published by NoName057(16), hackers managed to disrupt access to many Polish websites, including those of financial institutions Credit Agricole Bank Polska, Plus Bank, Raiffeisen Bank Polska, BNP Paribas Bank Polska, and Envelo. NoName057(16) also claimed that hackers had targeted the websites for the Polish Supreme Court, the Warsaw Underground, and the Port of Gdynia, among others. Cybersecurity firm Check Point Software Technologies confirmed that Russian hackers indeed carried out attacks against Polish targets in August 2023.

Hack-and-leak operation

The second election interference action, as defined by the Atlantic Council, is strategic publication (public disclosure) of illegally obtained information, mostly stolen via infrastructure exploitation. Hack-and-leak operations are a prominent example of strategic publication. In the context of elections, such operations frequently aim to undermine positions of candidates or parties that are perceived as less favorable by the foreign actors undertaking the operations.

The DFRLab was not able to find any public reporting on new public hack-and-leak operations conducted by foreign actors in the lead up to the 2023 parliamentary elections. However, materials from hack-and-leak operations, carried out by Ghostwriter in 2020 and 2021, were resuscitated and amplified ahead of the 2023 elections.

In 2021, Ghostwriter hacked the private email account of Michal Dworczyk, then-chief of the chancellery for Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki and stole a large amount of both state and private materials. Ghostwriter subsequently launched a Telegram channel, Poufna Rozmowa (“Confidential Conversation,” handle @poufnarozmowa), but Telegram reportedly blocked the channel at the request of the Polish government. After this, the operators behind the channel created the namesake website poufnarozmowa.com (unavailable as of December 1), where they continued to release the hacked documents. (The Telegram channel has since been resurrected as @poufnarozmowa2.)

The Polish government attributed Ghostwriter’s attack to the UNC1151 espionage group, which according to cybersecurity firm Mandiant is affiliated with the Belarusian intelligence service (KGB), while Recorded Future argued that Russia’s GRU was behind UNC1151. Having been embroiled in hack-and-leak scandal, Dworczyk resigned from his position in September 2022. Polish authorities stated that around 2,000 people had been targeted by Ghostwriter by the end of 2021 and around 700 attacks had been successful, of which 40 percent targeted Polish politicians. It seems that the main objective of the hack-and-leak campaign against Dworczyk was to undermine trust in state institutions.

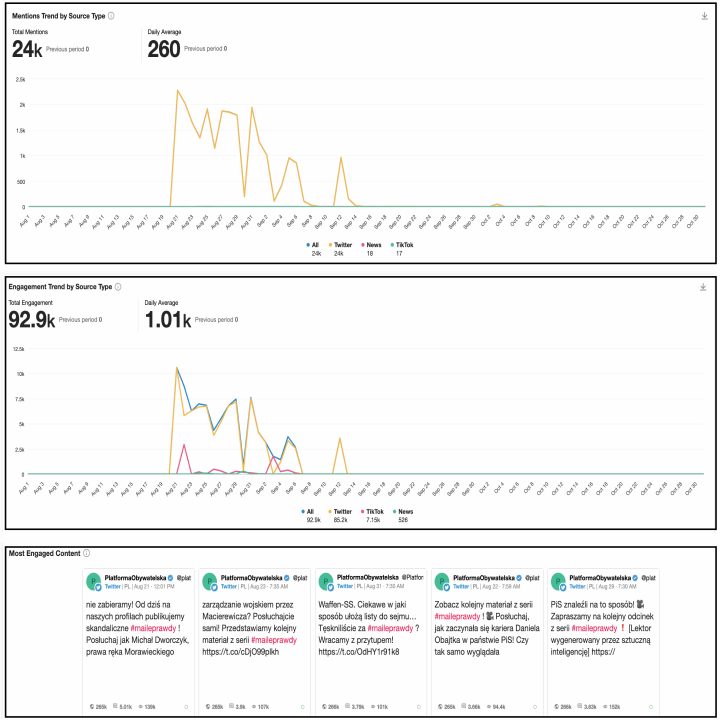

Two months before the 2023 parliamentary elections, the main opposition party, Civic Platform, started to amplify leaks from Dworczyk’s inbox on social media. Civic Platform launched a hashtag #maileprawdy (#emailsoftruth in English) to disseminate conversations between high-level Polish officials, as leaked from Dworczyk’s email inbox. As of the day of the elections, October 15, Civic Platform had promoted fourteen videos based on the leaked materials, mainly featuring hacked emails between then-Prime Minister Morawiecki and other Polish politicians. In the videos, Civic Platform used an AI-generated voice resembling that of Morawiecki reading quotes from the leaked emails. The DFRLab found that a hashtag, #maileprawdy, around the emails launched on August 20, 2023, and garnered over 24,000 mentions between August 20 and October 15. The most engaged-with content on X (formerly Twitter) to use the hashtag were tweets from Civic Platform’s account.

Civic Platform’s decision to amplify the earlier Ghostwriter leaks ahead of elections was problematic for at least two reasons. First, foreign threat actors carried out the original hack-and-leak operation, and a political party amplifying such leaked content ahead of elections gives additional visibility and oxygen to the activities of those hostile foreign actors. Second, it remains unknown how much of the content leaked by UNC1151 was authentic and how much was fabricated, and Civic Platform may therefore have unwittingly amplified falsehoods, created by UNC1151, to undermine the reputation of the victims. The recent dissemination of older hacked materials also demonstrates that the tactic is relevant, useful, and a long game: UNC1151 hacked Polish politicians two years ago, and the stolen materials were amplified in the Polish information space ahead of a later political event, in this case the 2023 elections; that a political party used that material – regardless of whether it knew or had any concern about the source of the leaked material – only served to validate the method of the earlier attack.

False-front engagement with Polish audience

The third type of interference action identified ahead of the 2023 elections was false-front engagement, which entails hostile foreign actors deploying fake social media profiles in order to interact with an audience in a target country and manipulate public opinion. Examples of false-front engagement for election interference include activities of the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA), which used hundreds of fake social media accounts to impersonate US citizens and exacerbated polarization ahead of the 2016 US presidential elections. This method has not been used against Poland at large, but at least one Telegram channel, Ktoś (“someone”) posted election-related messages. Some experts believe that pro-government Belarusian actors created and managed the channel. The DFRLab’s investigation into this Telegram channel also revealed that that the administrators of the channel might be native Russian speakers. However, this channel claims to be Polish in its biography, a self-written attribute that could easily be fabricated and, if so, could be used to mislead its audience about the true origin of the channel and provide it unwarranted credibility.

On October 4, 2023, Ktoś posted about how Polish voters should boycott a referendum as proposed by PiS, writing that the best way to do so was to refuse to accept paper ballots or to tear them up. The channel also argued that the referendum was a huge fraud. One of the referendum questions asked Polish voters whether they would “support the removal of the barrier [border wall] on Poland’s border with Belarus?” The wall was constructed by the PiS-led government in 2022 in order to stop illegal crossing attempts from the territory of Belarus, and Poland’s then-Minister of Defense Mariusz Błaszczak accused leaders of the opposition Civic Platform party of opposing construction of the wall and having an intention to remove it. In 2021, 66 percent of Poles supported their government’s decision to build the border wall and, by formulating the referendum question this way, PiS tried to embue the opposition party with a negative perception ahead of the elections. Belarusian authorities opposed the construction of the wall, with Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka calling the wall a “stupid idea” in 2021.

Five days later, on October 9, the Ktoś Telegram channel published another post declaring that the possibility of election fraud in Poland was too high and that Polish organizations were doing their best to minimize the possibility of fraud. On October 13, Ktoś shared a Telegram post from Kresy.pl channel; the post – which provided no corroborating evidence – alleged that a nonprofit organization affiliated with PiS had ordered around 30,000 fake ballots that would not be visually different from the real ballot. The post concluded that, most likely, this was an attempt to conduct mass fraud. Another anonymous Telegram channel, Anielskie Siostry Jasnowidzki (“Angelic Clairvoyant Sisters”), which is reportedly managed by Russians, wrote in August 2023 that the parliamentary elections in Poland were “a sham” and also posted a video (now no longer available) that reportedly argued that the election results had been falsified in advance. It should be noted that Polish politicians across the political spectrum are generally antagonistic toward Russia, and so Russian actors most often simply seek instability in the country, rather than supporting a particular side or its politics; hence, in this case, they were calling a PiS-supported referendum a sham while simultaneously attacking the more overtly pro-EU (i.e., and therefore counter-Russia) Civic Platform elsewhere.

Sentiment amplification

Sentiment amplification is yet another inteference action witnessed during the 2023 parliamentary elections and is used by foreign actorsto amplify biased viewpoints as a means of undermining trust in state institutions or creating divisions within a target society ahead of elections. Russian and Belarusian actors tried to exacerbate existing fault lines in Poland ahead of the October elections.

In the 2023 elections, the subject of Ukrainian refugees was one of the most divisive topics. On August 24, Polish-language Telegram channel Niezależny Dziennik Polityczny (“Independent Political Journal”), which is believed to be managed by foreign pro-Kremlin assets, wrote that Polish authorities were hiding the fact that Ukrainian refugees were the source of a Legionella bacteria outbreak in the southeastern Polish city of Rzeszów in August. The Telegram post claimed that four people, who died from Legionnaires’ disease (the disease form of the bacteria), had been helping Ukrainians in a refugee facility. This attempt to exacerbate anti-refugee sentiment presented refugees as a threat to the Polish people. Pro-Kremlin Russian media outlet EurAsia Daily also wrote that the Legionella outbreak came from Ukraine.

Anielskie Siostry Jasnowidzki, the channel noted above that had claimed the elections were a “sham,” wrote on August 26 that the birth rate in Poland was sharply declining and editorialized that no more Poles needed to be born because the country had already been “handed over to someone else” and that “farmhands have already arrived from the East,” both of which implied a supposedly detrimental impact of Ukrainian refugees. On August 24, the same channel wrote that the Polish government had destabilized its own country by letting millions of Ukrainians into Poland. The post claimed that Poles are so divided that they will no longer be able to defend Poland from the “Ukrainian element.” By exacerbating anti-Ukrainian sentiment ahead of the elections, foreign actors likely hoped that Poles would vote for those political actors during elections who advocate for reducing support for Ukraine.

The case at the border

Hostile and seemingly foreign actors also tried to aggravate the situation at the Poland-Belarus border in the lead up to elections. In Summer 2023, representatives of Polish government argued that Belarusian authorities were attempting to destabilize the situation in Poland by directing more people from Middle Eastern countries toward the two countries shared border.

According to official statistics, the Polish Border Guard has registered 19,000 illegal crossing attempts in 2023 to date, while this number was less than 16,000 total for 2022. The Polish Border Guard registered the highest monthly number of illegal crossing attempts – around 4,000 – in July 2023. Based on this, the Border Guard requested that the Ministry of National Defense send another thousand soldiers to the Polish-Belarusian border. On August 7, the Commander-in-Chief of the Border Guard, Major General Tomasz Praga, stated about the situation on the border: “we have another wave of illegal migrants and another stage of the hybrid war.” As with previous years, most of the political discussion in 2023 has focused on the impact of the migrants on the destination countries, while ignoring the migrants themselves and the circumstances behind their rationale for migrating.

Poland has been dealing with a surge of migrants and refugees on its border with Belarus since August 2021. After the European Union imposed sanctions on Belarus in May 2021, President Lukashenka directed a large number of migrants and refugees to its borders with Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia. The migration crisis, manufactured by Belarus and exacerbated by domestic politics in the EU countries, created a pressure for the EU member states to deviate from human rights commitments while handling the crisis as they refused to admit asylum seekers coming from the territory of Belarus and pushed migrants and refugees back toward Belarus, depriving them the right to seek protection. Belarusian authorities then used this response to present Poland and Baltic states in a negative light.

The border crisis has aggravated social divisions in Poland. In October 2021, people held protests across the country against the inappropriate handling of refugees and migrants by the Polish border guard. Later, in March 2022, the Polish police arrested several activists who tried to help the refugees and migrants caught at the border.

Using the long-running crisis as a pretext, Belarusian governmental as well as Polish-language pro-Belarus Telegram channels amplified stories about the “harsh measures” of Polish border guard ahead of the 2023 elections. On October 12, Belarusian Telegram channel FM BORDER | Facts and Opinions wrote that Polish border guards are killing pregnant women on a border. The next day, on October 13, the Investigative Committee of Belarus posted on Telegram that a 32-year-old was found dead at the border on October 12 and that he was found together with his 29-year-old friend, referred to as an “eyewitness,” who allegedly told a Belarusian border guard how his friend died. The Telegram post claimed the 29-year-old and his now-dead friend managed to enter and stay in Polish territory for a few days. The eyewitness allegedly claimed that the 32-year-old “needed insulin therapy and, having lost all his strength, could not move independently.” The eyewitness also reportedly claimed that Polish security forces discovered him and his friend and, instead of providing medical assistance, ordered the eyewitness to drag his exhausted friend to the fence (on Poland-Belarus border), where he later succumbed. The Telegram post declared that “he died on the shoulders of his friend in front of the Polish security forces.” The Polish-language pro-Belarus and pro-Russia Telegram channel NewsFactoryPL amplified the story on the same day.

The topic of the migration crisis on Belarus-Poland border triggered additional controversies ahead of the elections. In September, Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland released a new movie “Green Border,” a fictional story allegedly based on real events. The film is about Syrian refugees who try to cross the Poland-Belarus border, after which Polish activists risk their own safety to help the refugees. The film also features a young border guard who at first follows his commander’s orders but who later starts to question those orders with remorse. Polish authorities criticized the film harshly, including Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro, who compared it to Nazi propaganda, and President Andrzej Duda, who described the movie as “anti-Polish.”

“Green Border” screenings in several Polish cities were met with protests. In Krakow, a protest against the movie, organized by the All-Polish Youth nationalist organization was met with a counter-protest organized by activists from “Family Without Borders,” who provide help to refugees. During the movie premiere in the city of Bialystok, right-wing activists, led by Deputy Marshal of the Podlaskie Voivodeship Sebastian Łukasiewicz, verbally attacked Holland, who was attending the premiere. Thus, the border crisis, as orchestrated and exacerbated by a foreign actor in the form of the Belarusian authorities, has become a significant topic of conversation and political activity beyond the border itself and, in this way, contributed to more division and polarization ahead of the October parliamentary elections.

Through state media

In August 2023, Radio Belarus, owned by state-controlled entity Belteleradio, launched a YouTube channel in Polish, which it followed by launching a Telegram channel in Polish on September 6. Belarus used these channels to delegitimize electoral processes by fostering distrust in the electoral process and democracy more generally.

On October 11, International Radio Belarus posted an interview (given in Polish) with a pro-Belarus Polish commentator in which he stated that “Polish elites betrayed the country” and that the Polish electorate does not have hopes that anything will change after October 15.

Belarusian state-affiliated actors also tried to manipulate Polish sentiment through overt sources ahead of Polish elections. One day before Poland’s parliamentary elections, Belarusian state-controlled media outlet BELTA launched its Polish-language news website. The website mainly features interviews and statements from Belarusian authorities as well as from Poles who are friendly toward Belarus. Iryna Akułowicz, director of BELTA, claimed that the Polish version of the website would be “an opportunity to reach our neighbors, ordinary Poles, with what their own authorities are trying to hide from them.”

On election day, October 15, BELTA selectively amplified a story about supposed violations of electoral law, while a separate article the day prior had quoted former Polish President Lech Wałęsa as saying that there was a risk of a civil war in Poland. (A civil war has yet to take place.) Another article from BELTA quoted pro-government commentator Igor Shishkin saying that large-scale protests were possible in Poland after the elections. (No such large-scale protests have taken place since October 15.)

Fabricated content

Foreign actors also used fabricated content, another of the interference actions as detailed by the Atlantic Council, in order to sow confusion and societal division ahead of the elections. Foreign influence operations against Poland are frequently underpinned by forgeries and fake evidence. After Lukashenka stated on July 23 that the Wagner Group mercenaries stationed in Belarus had asked for permission “to go on a trip to Warsaw and Rzeszów,” forged photos appeared on Telegram and on social media allegedly confirming the presence of a Wagner fighter on Belarus’s border with Poland. On August 14, the Polish Internal Security Agency (ABW) announced the detention of two Russian citizens, Aleksei T. and Andrei G. (ABW did not release their full names), who they allege placed around three hundred Wagner recruitment posters in Krakow and Warsaw between August 10 and 11. The posters featured Wagner’s name and logo alongside the English text, “We are here” and “Join us.” The posters also contained a QR code that led to a Russian-language Wagner recruitment website, “группа-вагнера.online” (“Wagner-Group.Online”). Stanisław Żaryn, the secretary of state for the chancellery of the prime minister of Poland, said on X (formerly Twitter) that the arrested Russians’ activities represented an element of “hybrid war” against Poland and that they intended to intimidate the country’s society.

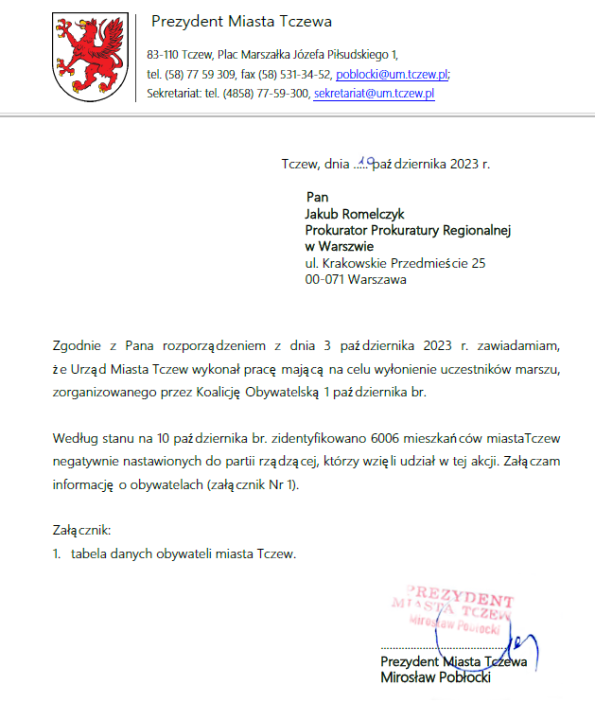

On October 13, website Polskanews.org published an unverified story that PiS had allegedly collected data of the participants in the “the Million Hearts march,” which the opposition parties organized for October 1, and that PiS had supposedly sent it to the prosecutor’s office. The article claimed that Polskanews.com had reportedly received a letter from a person working in the office of Polish Tczew city hall; the article continues, alleging that the letter was supposedly written by Mirosław Pobłocki, the president of Tczew (in Poland, the head of a local government territorial body elected through direct elections in urban communes with a population exceeding 100,000 people is called “president”). In the forged letter, Pobłocki reports that 6,006 residents of Tczew who took part in the Million Hearts March also had “a negative attitude toward the ruling party [i.e., PiS]” and referred them to the Polish prosecutor’s office. The attachment to this letter allegedly contained the personal data of 6,006 residents.

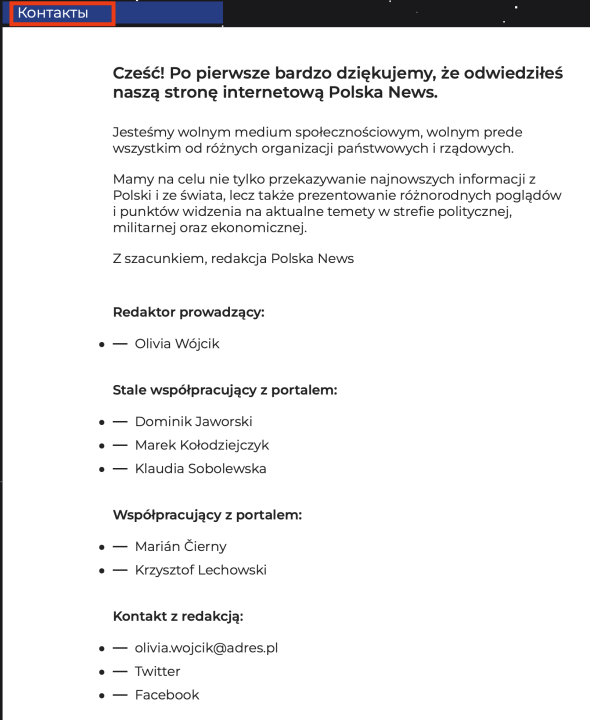

The DFRLab was not able to find any other information about or posts featuring this letter on the internet, and no other Polish media outlet reported on it, rendering its authenticity unknown. The DFRLab examined Polskanews.org in an effort to better understand the source of the letter. The website included information about its supposed editorial team, but the listed journalists were otherwise absent in follow-up Google search results. More specifically, the DFRLab was not able to find information about the managing editor of Polskanews.org and the people who have seemingly collaborated with the portal.

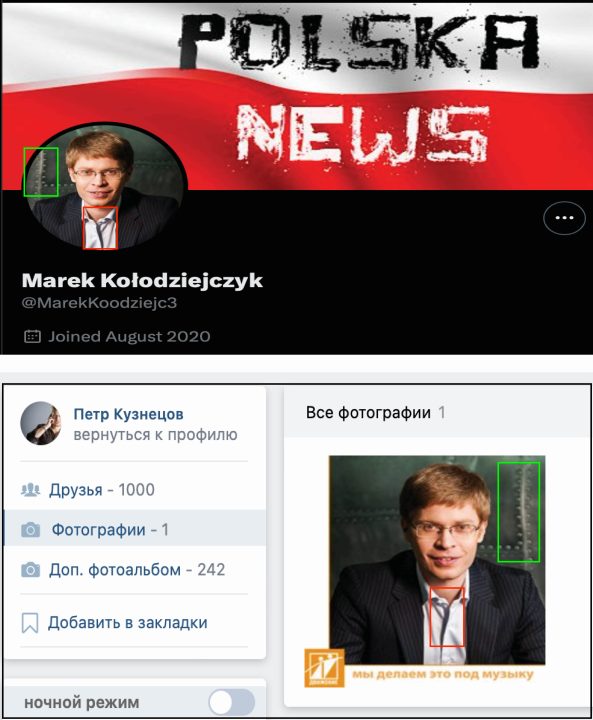

However, the button for the outlet’s X account in the contact section of Polskanews.org leads to the X account for Marek Kołodziejczyk, who according to Polskanews.org website, regularly writes for the portal. The Kołodziejczyk account has shared Polskanews.org articles on X, the last time in July 2021, and nearly every single post ever shared by the account contained URLs for Polskanews.org. A reverse image search for the the account’s profile photo revealed that a user on Russian social media network VKontakte, Petr Kuznetsov, had used a reversed version for his profile picture. The DFRLab was able to find Petr Kuznetsov’s Instagram account as well. The available evidence indicates that Marek Kołodziejczyk’s profile photo on X was likely stolen from Petr Kuznetsov, an indicator that the X account is fake.

Moreover, it seems that the Polskanews.com website steals content from other websites and that only a small portion of it is original content. For instance, some Polskanews.com articles (here and here) were verbatim copies of posts to Wprost.pl (here and here). Another strange aspect is that the title on the contact page for Polskanews.org is written in Russian – “контакты” (contacts), while the remainder of the page is in Polish.

On top of this, the Polskanews.org article featuring Pobłocki’s supposed letter was amplified by Belarusian Telegram channels Yellow Plums Premium and Shvarka News in Russian. Given the lack of corroborating stories on the letter and the dubious nature of the website, it is likely that the letter was forged, especially given the particularly provocative claims it contained.

As documented above, available evidence demonstrated that foreign or seemingly foreign actors undertook a variety of actions to target the Polish information environment and cyberspace ahead of the October 15 parliamentary elections. Infrastructure exploitation attempts included phishing attacks against Polish politicians and DDoS attacks against Polish websites. The resurfacing of hack-and-leak operation showed that election interference can be a long-term process. Sentiment amplification, false-front engagement, and distribution of fabricated content by foreign and seemingly foreign actors tried to capitalize on existing societal tensions and fault lines in Poland. Underlying all of these efforts was an attempt to delegitimize state institutions and to undermine trust in the electoral process.

Cite this case study:

Givi Gigitashvili, “How foreign actors targeted Polish information environment ahead of parliamentary elections,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), December 13, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/12/13/how-foreign-actors-targeted-polish-information-environment-ahead-of-parliamentary-elections/.