Lessons learned from South Africa’s 2024 elections

Independent media and civil society worked overtime to mitigate the spread of disinformation, while generative AI played only a limited role

Lessons learned from South Africa’s 2024 elections

Share this story

Banner: Generative AI image of Julius Malema. (Source: @Brettbenraphael/archive)

False and misleading electoral information circulated widely on social media platforms over the course of the 2024 South African general election. Prior to the vote on May 29, mistrust in political processes among citizens and disillusioned youth sparked doubts and misinformation about the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) and election integrity in South Africa. The elections resulted in the African National Congress (ANC) losing its parliamentary majority for the first time since 1994, gaining only 40 percent of the vote.

In this brief, we explore efforts by civil society, independent media, and social platforms to mitigate the proliferation of mis- and disinformation. We also examine the proliferation of false claims regarding automatic voting for the ANC and the role of generative AI during the election cycle.

Efforts to mitigate the impact of electoral misinformation

Ahead of the elections, South Africa’s Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) partnered with Google, Meta, TikTok, and civil society organization Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) to curb the spread of disinformation. MMA’s Real411 platform solicited online complaints from voters about content containing disinformation, which was vetted and shared with IEC’s Directorate for Electoral Offences. According to MMA, this resulted in “roughly a six-fold increase in complaints during the election period.”

During the same time period, fact-checking outlet Africa Check hosted its South Africa Election Information Hub, verifying online claims and debunking misinformation. Meta partnered with Africa Check and activated an operations center to identify “potential threats across our apps and technologies in real time.” The company also launched a Voter Information Unit and sent out reminders to encourage its South African users to seek out “authoritative information” from the IEC website.

Elsewhere online, the platform X – formerly known as Twitter – struggled to combat elections-related disinformation in South Africa. Community Notes, in which X users can crowdsource their own fact-checks, were an imperfect solution to misinformation on the platform. As was the case during recent elections in India and the UK, Community Notes can sometimes be misleading, or published after the misinformation in question has already proliferated. As the DFRLab has documented in prior news events and elections around the world, X continued to be exploitable by malicious actors seeking to take advantage of trust and safety gaps that allow for the amplification of misinformation and disinformation with minimal repercussions on the platform.

The decline in access to research tools globally from technology and social media platforms has hindered disinformation research and efforts to expose and hold perpetrators accountable. In South Africa, a group of twelve social media research organizations called on platforms to “allow open access to data holdings” and access to Application Programme Interfaces (APIs). With major platforms such as Meta and X reducing API access in recent years, research organizations and other entities across South African civil society had fewer tools available to them to identify information operations or expose the malign actors perpetrating them.

Within this broader context, the IEC warned voters to “stay informed and beware of disinformation” and debunked misleading and disinformation claims on social media. The debunked information included claims that polling station voting pens employed evaporating ink, misleading footage of discarded election materials, and bribery accusations against the IEC, among others.

The IEC also issued a statement clarifying its Elections Results Dashboard following claims that the IEC changed votes on the dashboard following the count. Additionally, debunked claims of vote rigging and uncounted votes circulating on different social media platforms. Other rumors and electoral misinformation included false or misleading claims of celebrities endorsing the MK Party, conspiracy theories that the CIA allegedly planned to start a war in South Africa and blame MK for it, and efforts to embarrass the ANC by falsely accusing it of installing an open-air toilet.

Case study: automatic voting rumors and voter mistrust

Online rumors and electoral misinformation feed off existing political and social divisions and exacerbate mistrust in elections and political processes. Among the most persistent false claims in South Africa’s electoral cycle was the allegation that if a person did not vote, vote counters would automatically tabulate it as a vote for the ruling party, the ANC. The rumor circulated on multiple social media platforms over the course of the election.

South African media and civil society responded to this rumor on multiple fronts. In February 2024, the Daily Maverick produced a YouTube video warning voters against falling for this misleading claim, noting that it had surfaced during the election “with particular force.” The video garnered more than seven thousand views and also sparked a discussion thread on Reddit. It proved even more successful on TikTok, where it attracted nearly 150,000 views and 3,000 likes.

The following month, Africa Check produced its own fact-check on the false claim, which it published on Facebook and other platforms. Meanwhile, Section27 published a detailed fact-check exploring the rumor, explaining how South Africa’s Electoral Act of 1998 and the IEC work to avoid mistaken or inauthentic vote counts.

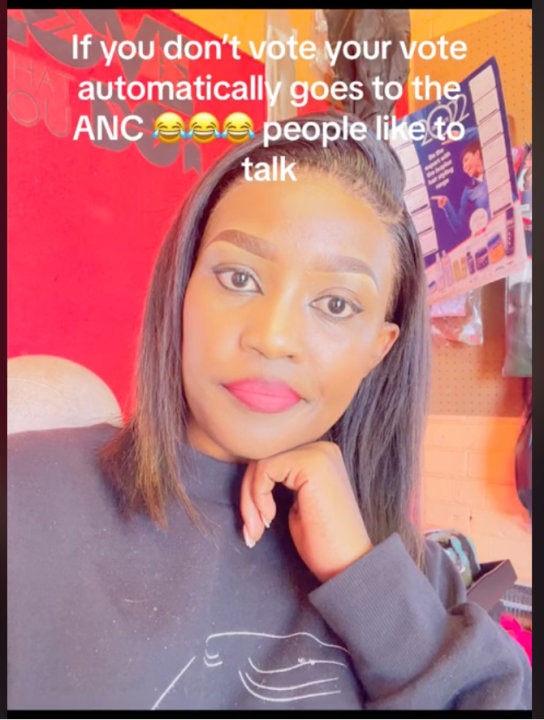

It is also notable that South African TikTokers also raised questions about the rumor when they came across it online. “If you are a registered voter and you don’t vote, you just don’t vote – there’s no vote to get counted,” TikToker Kaitlin Rawson communicated in a video that garnered nearly 14,000 views. Similarly, user @thatasiangirlza discussed the rumor as part of a fact-check she produced labeled “3 common voting myths.” In another instance, a TikToker uploaded a still photo of themselves with a skeptical expression, accompanied by text and a synthetic voiceover stating, “If you don’t vote your vote automatically goes to the ANC 😂 😂 😂 people like to talk.”

Notably, this particular rumor is not unique to the 2024 election cycle. Identical claims can be found on social media going back to at least 2011, indicating deeply rooted mistrust among some voters in South Africa. And when it resurfaced in 2019, the IEC took to Twitter to note, “There is absolutely no truth to the rumour that if you don’t vote your vote will go to the ruling (or any other) party. Only valid votes cast in an election are counted in the result. Thanks for checking.”

Despite these efforts, the rumor persisted throughout the election season. When Africa Check posted a TikTok video warning people about the rumor, a TikTok user responded cynically, “How do we even know if the Africa check is genuine?”

Case study: the impact of generative AI

Throughout 2024, election observers around the world have expressed concerns that generative artificial intelligence (GAI) could be employed to great effect to create disinformation, particularly in the form of videos commonly referred to as deepfakes. While there were a number of cases of GAI being employed in South Africa’s election cycle, their overall volume was quite limited when compared to the volume of more traditional forms of disinformation.

When instances of GAI disinformation occurred, however, fact-checking organizations were responsive. For example, both Africa Check and Rest of World fact-checked a synthetic clip of the American rapper Eminem purportedly using profane language to denigrate the ANC, with an animated EFF flag fluttering across the bottom half of the clip. The video appears to have first surfaced on TikTok before being removed from that platform. Flipside Radar re-uploaded the video on Instagram and labeled it as “humour,” though the platform added its own warning, labeling it “False information. Reviewed by independent fact-checkers” alongside a link to the Africa Check article debunking it.

Similarly, Africa Check and Rest of World debunked a deepfake of US President Joe Biden appearing to threaten the ANC. First surfacing on TikTok, it was eventually deleted but reappeared on Facebook and Twitter. Africa Check also noted they had received a copy of the fake video through its What’s Crap on Whatsapp initiative, which allowed members of the public to forward suspicious WhatsApp posts to Africa Check investigators.

In the video, the synthetic manifestation of the US president stated, “If the ANC wins the next election, we will impose immediate sanctions and declare South Africa an enemy state. The whole of the European Union will back us with this, and together we will fight for the freedom of South Africans.” An X user who shared the video noted that it was a deepfake, attributing it to “AI Joe Biden.”

In another instance, Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla, the daughter of former South African president Jacob Zuma, used her X account to amplify an AI-generated TikTok video of former US President Donald Trump. “Greetings…all South Africans,” the ersatz Trump states stiltedly. “My name is President Donald Trump. I urged all South Africans to vote for uMkhonto WeSizwe.”

Zuma-Sambudla appears to have been aware the video was fake, however, given that her post included multiple laughing emojis. Nonetheless, it garnered more than 150,000 views and a “manipulated media” label from X. Zuma-Sambudla was later elected to represent her party in parliament.

Interestingly, at least two other X accounts replied to the fake video with fakes of their own, using a free tool called ParrotAI to manipulate Trump’s voice over the same video clip. “Don’t vote for the MK party,” the first reply video stated. “The last video posted by this stupid party is generated using AI, so please do not take anything serious by these AI-generated apps that are circulating online. And yes – please vote for the IFP.” The second reply video took a similar approach. “Hey South Africa, the above video is fake,” another fake Trump implored. “Please vote for EFF.”

Internet users also disseminated synthetic images to influence the South African electorate. In some instances, these images were realistic enough to easily stump casual viewers. For example, AFP Fact Check documented a May 6 Facebook post appearing to show a photo of endless potholes pock-marking a road, with Cape Town’s Table Mountain looming in the background. “The other side of Cape Town,” the post read. “Mthatha is Ma Home Town.” According to AFP, “The post suggests that the Western Cape province needs better governance.”

Utilizing a reverse image search, AFP proved that the photo in question was a synthetic art project, originally uploaded and labeled as “Ai Art Photography” on April 21. One user responded to the image with a warning: “AI created… but everyone will believe these photos.”

Other generative images were less photorealistic, likely intended to evoke an emotional response rather than to deceive voters. For example, on April 17, the Referendum Party posted a pair of generative images. One showed two rows of dilapidated buildings extending into the distance, intersected by a stream of mud and rubbish serving as a thoroughfare, while the other depicted a colorful, idealized skyline with hot-air balloons soaring in front of Table Mountain. “In 2024, you will be voting for one of two possible futures,” the post stated. “Vote for security, freedom and prosperity for ALL the people of the Western Cape. Vote Referendum Party.”

The use of GAI continued well after the votes were counted. Two weeks after the election, a June 13 X post included an image purporting to show EFF leader Julius Malema crying and holding a balloon that read “9%,” in reference to the percentage of votes the party had garnered. The image was uploaded as a direct response to a tweet posted by Malema in which he offered encouragement to his supporters. While the image contains certain photorealistic elements, its colors, textures, and brightness are exaggerated, in some ways making it more akin to a political cartoon or caricature.

While there is no evidence that the relatively limited usage of GAI footage impacted the election results, its usage can contribute to sowing mistrust and division. While it is useful for voters to maintain a level of healthy skepticism, the growing use of GAI in subsequent elections will likely make them more cynical, potentially to the point of treating all content with a mistrustful eye. And it need not require the dissemination of photorealistic GAI content. As seen in the above examples, sometimes taking a more exaggerated or fanciful approach increases the likelihood of evoking an emotional response. While such efforts are often more satirical than anything else, the same techniques could be used to provoke racial animus, employing offensive stereotypes to fan the flames among individuals who might be prone to political violence.

Final thoughts

South African trends in content and information manipulation reflected the same informational challenges around the world this year, during which more than 80 elections are taking place. The information landscape surrounding South Africa’s 2024 elections and the various efforts to mitigate and combat electoral disinformation indicate that electoral periods are rife with false and unverified information, with independent media, civil society, and platforms working individually and in various partnerships to mitigate it.

Overall, entities such as the IEC and MMA, alongside media outlets such as Africa Check, Rest of World, the Daily Maverick, and AFP Fact Check, collectively responded to online rumors and suspicious footage, utilizing open-source research and investigative journalism techniques to debunk them. In contrast, platforms struggled in their ability to combat misinformation, at best mitigating it through content moderation or crowd-sourced fact-checking contributions. For future elections, as potential threats like generative AI likely mature into more effective vectors of disinformation, the IEC, independent media, and civil society will continue to play a critical role in educating the South African electorate and maintaining resilience in the nation’s democratic processes, but it remains to be seen if social media platforms can expand or rebuild their capacity to enforce content violations at scale.

Cite this case study:

Dina Sadek and Andy Carvin, “Lessons learned from South Africa’s 2024 elections,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), July 31, 2024, https://dfrlab.org/2024/07/31/lessons-learned-from-south-africas-2024-elections/.