Mythical Beasts and Where to Find Them: Data and Methodology

Learn more about the methodology and dataset behind Mythical Beasts and Where to Find Them: Mapping the Global Spyware Market and its Threats to National Security and Human Rights

Mythical Beasts and Where to Find Them: Data and Methodology

Mythical Beasts and Where to Find Them: Mapping the Global Spyware Market and its Threats to National Security and Human Rights is concerned with the commercial market for spyware and provides data on market participants. Focusing on the market does not presume that all harms from spyware stem from how it is acquired, or whether that acquisition is a commercial transaction with a third party (versus developed “in-house” by the customer). Some definitions of spyware differentiate it by the means with which it is acquired, creating confusion over the fundamental distinction between “spyware” and, for instance, “commercial spyware.”1“Prohibition on Use by the United States Government of Commercial Spyware That Poses Risks to National Security,” Federal Register, March 30, 2023, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/30/2023-06730/prohibition-on-use-by-the-united-states-government-of-commercial-spyware-that-poses-risks-to.

Spyware: is a type of malicious software that facilitates unauthorized remote access to an internet-enabled target device for purposes of surveillance or data extraction.1“Unauthorized” access separates spyware from myriad other services or tools that might be used to effectuate similar surveillance but which require a user’s consent at some stage e.g. downloading an application from a mobile phone app store. Spyware is sometimes referred to as “commercial intrusion [or] surveillance software” with effectively the same meaning.250 U.S. Code § 3232a – Measures to mitigate counterintelligence threats from proliferation and use of foreign commercial spyware, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/3232a. This research considers the “tools, vulnerabilities, and skills, including technical, organizational, and individual capacities” as part of the supply chain for spyware and the meaningful risks posed by the proliferation of many of these components.3Winnona DeSombre et al., “A Primer on the Proliferation of Offensive Cyber Capabilities” (Atlantic Council, March 1, 2021), https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/a-primer-on-the-proliferation-of-offensive-cyber-capabilities/.

… so “Commercial” Spyware?

Transactions across the spyware market may be less regulated than in-house development of spyware but they are far from the only source of harm and insecurity. Policies that seek only to mitigate harms from the commercial sale of these capabilities risk ignoring their wider harms and avoid the opportunity to address fundamental concerns over surveillance and the full spectrum of government uses of these technologies.

The debate over what constitutes legitimate uses of spyware is ongoing, but commercial sale is a poor proxy for the degree of responsible or mature use. History has shown that this market is only one, albeit significant, part of a wider proliferation challenge.2 Read more about the ‘breakout’ of “offensive capabilities like EternalBlue, allegedly engineered by the United States, used by Russian, North Korean, and Chinese governments” (DeSombre et al., Countering Cyber Proliferation). See also Gil Baram, “The Theft and Reuse of Advanced Offensive Cyber Weapons Pose a Growing Threat,” Council on Foreign Relations (blog), June 19, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/blog/theft-and-reuse-advanced-offensive-cyber-weapons-pose-growing-threat; Insikt Group, “Chinese and Russian Cyber Communities Dig Into Malware From April Shadow Brokers Release,” Recorded Future (blog), April 25, 2017, https://www.recordedfuture.com/shadow-brokers-malware-release/; Leo Varela, “EternalBlue: Metasploit Module for MS17-010,” Rapid7, May 19, 2017, https://blog.rapid7.com/2017/05/20/metasploit-the-power-of-the-community-and-eternalblue/. Many human rights violations associated with spyware occur in the context of their use for state security purposes (e.g., by intelligence agencies), highlighting the diverse harms and risks posed by the proliferation of spyware. These include what some researchers have termed “vertical” uses (by states against their own populations) and “diagonal” uses (against the population of other states, including diaspora).3Herb Lin and Joel P. Trachtman, ”Using International Export Controls to Bolster Cyber Defenses,” Protecting Civilian Institutions and Infrastructure from Cyber Operations: Designing International Law and Organizations, Center for International Law and Governance, Tufts University, September 10, 2018, https://sites.tufts.edu/cilg/files/2018/09/exportcontrolsdraftsm.pdf. There is some normative loading in the term “spyware” vs. the more functional “malware” or the rather impenetrable “commercial intrusion capabilities” but is beneficial to have a common term of art in many of these debates.

This report and accompanying dataset are mainly inclusive of investigations into vendors and suppliers that have been found selling spyware to governments across the world that have then used this software to abuse human rights. However, this is only one side of the coin. Far less data exists on the use of spyware for a myriad of intelligence and counterintelligence purposes, including “national security” missions both genuine and troubling. The report cannot resolve these tensions but does seek to frame them in service of a more immediate and practical purpose—and a better understanding of the market that provides the software tools and services to carry out these acts.

Commercial acquisition of spyware is not the root cause of its abuse. While this project is focused on bringing transparency to participants in the spyware market, it does not argue that only transactions through this market pose proliferation risks or harms.4As argued in previous work published by the Atlantic Council, proliferation “presents an expanding set of risks to states and challenges commitments to protect openness, security, and stability in cyberspace. The profusion of commercial OCC vendors, left unregulated and ill-observed, poses national security and human rights risks. For states that have strong OCC programs, proliferation of spyware to state adversaries or certain non-state actors can be a threat to immediate security interests, long-term intelligence advantage, and the feasibility of mounting an effective defense on behalf of less capable private companies and vulnerable populations. The acquisition of OCC by a current or potential adversary makes them more capable” (See: Winnona DeSombre et al, Countering Cyber Proliferation). To avoid further confusion in both analysis and policy the authors do not include the term “commercial” in the definition of spyware. While the debate continues about how to manage these risks, this project sheds better light on those buying, selling, and supporting this market.

A Final Note on Scope

Spyware works without the consent or knowledge of the target or others with access to the target’s device; thus, this report does not consider the market for so-called “stalkerware,” which generally requires physical interaction from an individual, most often a spouse or partner, with access to a user’s device.5“Stalkerware: What to Know,” Federal Trade Commission, May 10, 2021, https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/stalkerware-what-know. This definition also excludes software that never gains access to a target device, such as surveillance technologies that collect information on data moving between devices over wired (i.e., packet inspection or “sniffing”) or wireless connections. This definition also excludes hardware such as mobile intercept devices, known as IMSI catchers, and any product requiring close or physical access to a target device, such as forensic tools.6IMSI catchers are also referred to as “Stingrays” after the Harris Corporation’s eponymous product line; Amanda Levendowski, “Trademarks as Surveillance Technology,” Georgetown University Law Center, 2021, https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3455&context=facpub.

This definition is limited, by design, to disentangle lumping various other surveillance toolsets into the definition of spyware.

Building the Dataset

This dataset represents a meaningful sample of the market for spyware vendors, but it is not a complete record and this report can only speak to trends and patterns within this data, not the market as a whole. The data is confined to entities for which there is a public record (i.e. registered businesses) and for which public information links the vendor to the development or sale of spyware or its components.7For more see: Winnona DeSombre et al., A Primer on the Proliferation of Offensive Cyber Capabilities, Atlantic Council, March 1, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/a-primer-on-the-proliferation-of-offensive-cyber-capabilities/.

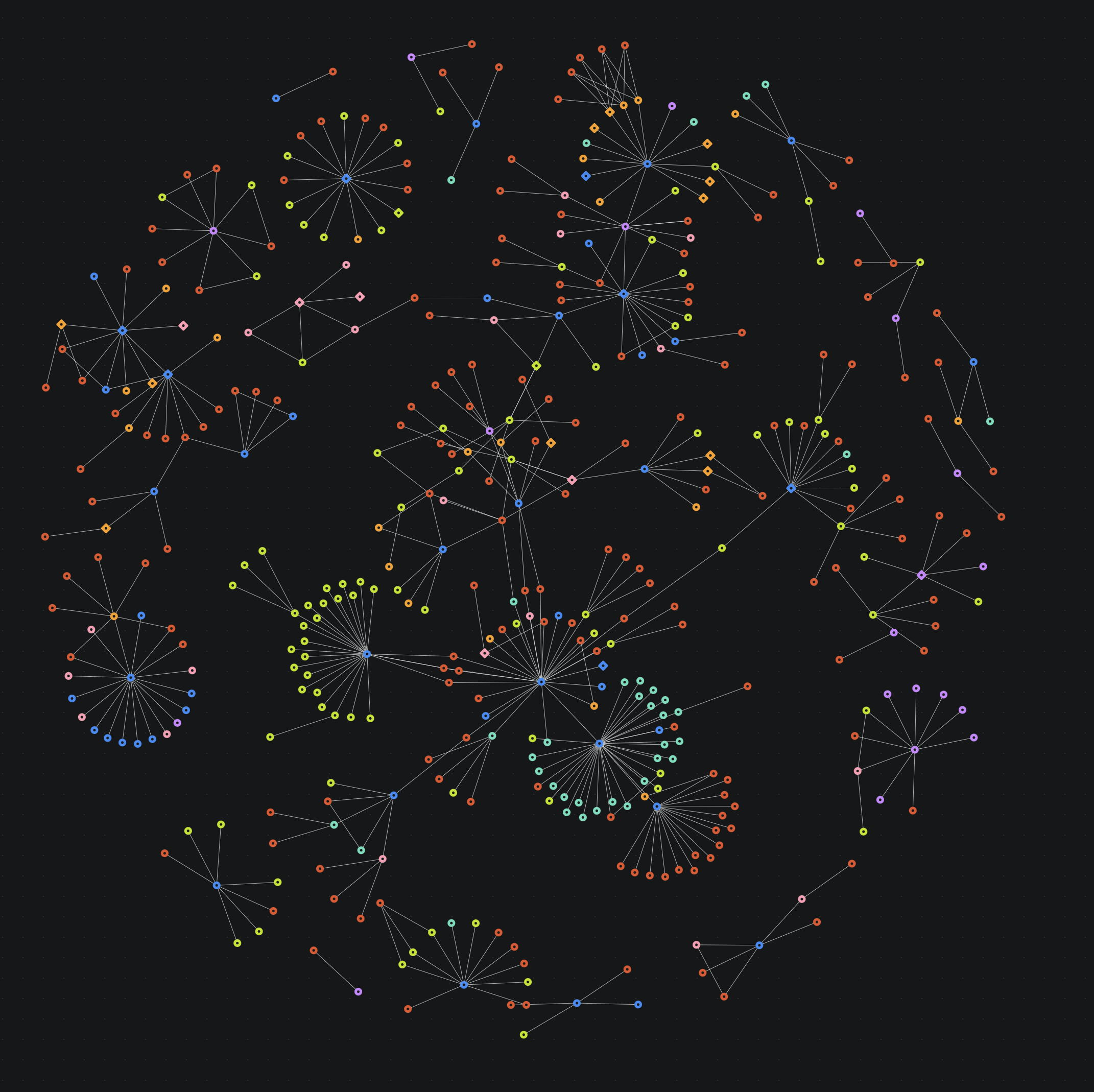

To develop a list of vendors, the authors started by creating an initial “most visible” list of those with the widest public exposure from the use of their wares, relying principally on public reporting from Amnesty International, Citizen Lab, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, as well as public reporting from a variety of news outlets. This initial set of vendors was the starting point for searching public corporate registries and a mix of public and private-sector corporate databases to profile each company in greater depth and find additional connections.

All the vendors identified through this process were included if they 1) publicly advertised products or services that matched the above definition of spyware, 2) were described as selling the same products by public reporting in the media or by civil society researchers, or 3) showed evidence of the products through court records, leaks, or similar internal documentation. As part of this search process, the team gathered records on subsidiaries and branches associated with each vendor, their publicly disclosed investors, and, where possible, named suppliers.

Each entity identified in this process was identified by at least two different open sources. In all cases for which data is available, the dataset includes vendor activities from the start of operation until 2023, or until records indicate that the vendor’s registration had ceased in a jurisdiction. The sources of public information on both firms’ activities and their organization varied but largely stemmed from different forms of corporate registration, records, and transaction data.

Government-Run Corporate Registries: perhaps the most useful type of source for the project to collect credible information on formal names, jurisdictions, and directors and run by respective governments. Perhaps the most comprehensive type of sourcing the authors found and could point to investor relationships. An example of corporate registration is the EU business registers, where researchers can look up if a business entity is registered in any European Union jurisdiction. Corporate registries were utilized to determine jurisdictions and legal registered name of a label, this type of source can be found in most of the rows.

Court Records: a resource that provided important names, dates, and relationships. Useful for certain vendors, like Appin Security Group, which was involved in a case before the Additional District Judge of the Rohini court in India that issued a summons to eight people associated with Reuters.

Opencorporates: a resource that pointed to corporate registries and linked to where a company by name was registered in based off jurisdiction and whether the information was publicly available. This source was typically credible but required very specific search terms to yield appropriate results. For example, if an entity has multiple names, it was recommended to search by its various names for more comprehensive results. This source was useful for finding jurisdictions, government databases, individuals, and dates. It was less useful for name changes and investor data. For example, the authors were able to find Dream Security, a company founded by an individual who also founded NSO Group, Shaliev Hulio, through Opencorporates.

Pitchbook: a paywalled resource for initial research and trying to determine how an entity describes itself. This source was useful for initial scoping of entities to add to the dataset but limited in scope. Some investors in the dataset were initially found in pitchbook, but further research was needed to determine the extent of their relationship with a vendor or supplier.

Crunchbase: a resource for initial research and trying to determine how an entity describes itself. Most content is behind a paywall. This source was useful for the initial scoping of entities to add to the dataset. Some investors in the dataset were initially found in pitchbook, but further research was needed to determine the extent of their relationship with a vendor or supplier.

Zaubacorp: a resource for Indian registered records. This source was useful for compiling government records across various government databases into one common searchable space. Its limitation was in the constrained jurisdiction it covered. For example, some of the individuals we discovered for CyberRoot Risk Advisory Private Limited were listed in this database, as well as holding companies like Wynard India Private Limited and its connection to Appin Security Group.

News Media: These were taken as mostly credible if the news outlet itself is reliable, but ideally with a secondary source supporting specific information claimed, especially if the news source itself did not link to external or additional sources within itself. More credible sources tended to point to corporate registrations supplied by governments or the entity in question. This type of sourcing was useful for leads in terms of finding alternative company names, dates for any activity, and finding new entities to incorporate into CSI’s dataset. News sources also served as a good start for finding investor data when accompanied by government sourcing.

Leaked Materials: a source for internal communications, advertisements, pricing, and establishing partner relationships. Particularly useful in mapping the vendors Memento Labs srl (formerly known as Hacking Team srl) and Gamma Group and mapping partnerships like that between Memento Labs srl and RCS Labs e.g. “Hacking Team Source Dump Map”.

Defining Entities in the Spyware Market

Disclaimer on Sources

More information: All sources for this dataset are open-source and were publicly available at the time of writing. For more on the kinds of data used in this project, see here. We are aware that some links have broken or been removed, and a handful of sources have been taken down in the wake of court orders. We are unable to replace, or host, copyrighted material. For any questions on sourcing, please email cyber@atlanticcouncil.org.

The Cyber Statecraft Initiative, part of the Atlantic Council Tech Programs, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.