Paid to post: Russia-linked ‘digital army’ seeks to undermine Moldovan election

Russia-linked operation active since at least 2024 is using paid ‘activists’ to target Moldovan vote

Paid to post: Russia-linked ‘digital army’ seeks to undermine Moldovan election

Share this story

BANNER: A man stands in front of a board with Moldovan political parties’ campaign posters ahead of the upcoming parliamentary elections. (Source: REUTERS/Vladislav Culiomza)

An operation with ties to Moscow is reportedly paying individuals to generate inauthentic accounts and disseminate false narratives, aiming to influence Moldova’s upcoming election. Moldova, having just emerged from its 2024 presidential election campaign and a razor-thin referendum in support of European Union (EU) integration, is heading back to the polls on September 28 for parliamentary elections. The 2024 elections were saturated by attempts to undermine the vote, from disinformation to vote-buying schemes. Yet, Moldovan President Maia Sandu told the BBC that she expects Russia to be even more aggressive this year in its financing and targeting of the vote.

Undercover investigations by the BBC and Ziarul de Gardă (ZdG) reveal new details about a “digital army” affiliated with Moscow that is seeding falsehoods into the Moldovan information space. Journalists infiltrated the operation by posing as activists, gaining access to secret Telegram groups, online training sessions, and inauthentic social media campaigns primarily active on TikTok and Facebook.

As part of their investigation, the BBC identified ninety accounts associated with the operation. The DFRLab reviewed the social media network identified by the BBC and found that it is tied to an online operation that was launched in the fall of 2024. The DFRLab has been monitoring the network since January 2025 and previously reported on the network’s attempts to accuse Sandu of interference in Romania’s election.

ZdG, Moldova’s leading investigative outlet, published a two-part investigation into the operation, detailing the narrative instructions participants received. Complementing the DFRLab’s August research, ZdG found that in July the network was instructed to “attack” Sandu by “claiming that she had intervened in Romanian elections and betrayed national interest since she holds citizenship of that country.”

This piece provides a comprehensive evidentiary review that supports the findings of the BCC and ZdG, enriched with a forensic analysis that shows the evolution of specific campaigns to better understand the Moscow-linked “digital army,” its modus operandi, the impact it seeks to generate, and the actors who benefit from this infrastructure.

The network’s scale

ZdG’s second publication revealed that by August, around 200 so-called “InfoLeaders” were recruited, although not all of them were active or performing tasks. These InfoLeaders are the digital foot soldiers tasked with producing and amplifying inauthentic social media content. The DFRLab analyzed the online activity of the InfoLeaders network and collected data from 253 inauthentic accounts, which we assessed based on activity frequency, posting patterns, and alignment with the narratives outlined in the BBC and ZdG investigations.

We found that the operation generated 28,708 posts, which collectively reached 55,367,950 views, 2,207,894 likes, 295,608 shares, and 239,016 comments across three platforms, at the time of writing. The network leveraged at least 173 TikTok accounts, fifty-nine Facebook accounts, and sixteen Instagram accounts. As of the time of writing, most of the accounts had been deplatformed.

While the majority of the InfoLeaders’ activity was centralized on TikTok, the network suddenly became active on Facebook in the weeks following Romania’s May 4, 2025, election, as posting activity increased, reaching an all-time high during the last week of June 2025. According to ZdG, new “InfoLeaders” were being recruited until early July. In July and August, curators intensified their efforts to grow followers and maximize reach by election day. Between July and September, the network posted 12,655 posts, accounting for approximately 44 percent of the total volume of collected posts.

Network organization

ZdG’s investigation revealed that the operation is organized into hierarchical groups, managed by Russian-speaking “curators” who function as the operation’s command-and-control center, distributing tasks, guidelines, and performance expectations to hundreds of participants. Recruits begin as communication activists and, once they prove reliable, are promoted to full-fledged InfoLeaders.

The apparent first tier involves the group, “Training of Communication Activists,” which recruited and trained “activists” to disseminate messaging aligned with the political agenda of exiled oligarch Ilan Shor. The second tier, “InfoLeader,” pursued a broader mission: shaping Moldova’s information space in ways favorable to Moscow while concealing its association with Shor’s “Victory” Bloc, a political entity sanctioned by the EU Commission for its affiliation with the oligarch. Shor was mentioned in 536 posts originating from the network.

The network was also territorially organized, covering Moldova’s districts and Chisinau’s sectors, and expanded across the south, center, and north of the country. Coordination followed a strict rhythm: pre-recorded video tutorials during the day and nightly audio calls at 8 p.m. Curators used Telegram bots to assign tasks, collect links to published content (used to determine payouts), and monitor compliance. Each activist was required to produce a fixed number of posts or comments daily, ensuring the narratives remained prominent.

To reduce the risk of detection, curators insisted on personalization. Activists were instructed to tailor their messages, but were told to strictly copy and paste the hashtags. They even organized “SMM master classes” to teach participants how to edit content and disguise coordinated activity as organic. The DFRLab observed a similar tactic during Calin Georgescu’s Romanian presidential campaign, when Telegram groups circulated video tutorials for editing apps with the intention of teaching users how to personalize their content.

In addition to producing original posts, activists were encouraged to systematically amplify one another’s content by liking, sharing, and commenting, creating the illusion of widespread organic engagement.

The organizational model bears resemblance to what the DFRLab documented in Romania’s 2024 presidential race. In both cases, Telegram groups acted as central hubs for regional segmentation, content distribution, and cross-platform dissemination to TikTok and Facebook. These parallels indicate that pro-Kremlin digital operations are not isolated experiments, but rather part of a recurring playbook that is modular, exportable, and refined to fit national contexts.

Hashtag crafting and testing

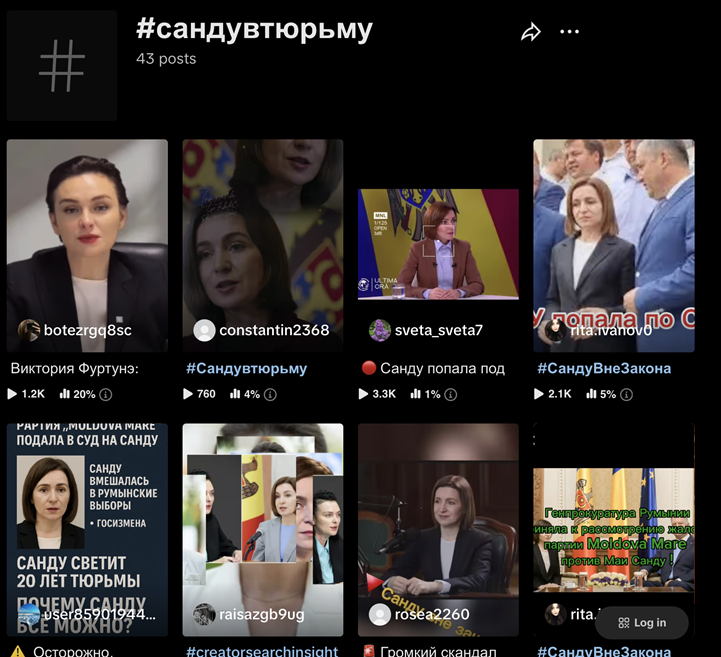

Hashtags were a central pillar of the operation, used to drive trends and measure impact. While participants could adapt the post text, they were instructed to follow the curators’ hashtag instructions precisely. Curators admitted to inserting spelling or grammatical errors to track campaign reach. The DFRLab found that, in total, the network has used 20,707 hashtags since its inception.

The network organized digital flash mobs on TikTok tied to specific hashtags chosen in advance, amplifying visibility and acting as exercises for operators. Participants would post synchronously, using the same hashtag, and send links to a Telegram bot for validation.

In December 2024, curators launched a New Year’s flash mob using the hashtag “#WeWarmOurselvesWithDances” (#греемсятанцами in Russian and #NeîncălzimDansînd” in Romanian). The operatives who received the most views were promised an iPhone. This appears to be one of the earliest digital flash mobs from the operation. At the time, each hashtag was associated with between 22 and 27 posts.

Later in January 2025, the operators were reportedly tasked with posting content targeting Ion Ceban, Chisinau’s current mayor, spreading the narrative that the city was on the “brink of bankruptcy.” Overall, 117 social media posts directly targeting Ceban appeared from the network throughout 2025.

Across multiple social media accounts, primarily on TikTok, the narratives are visible in chronological order, as dictated to the Infoleaders.

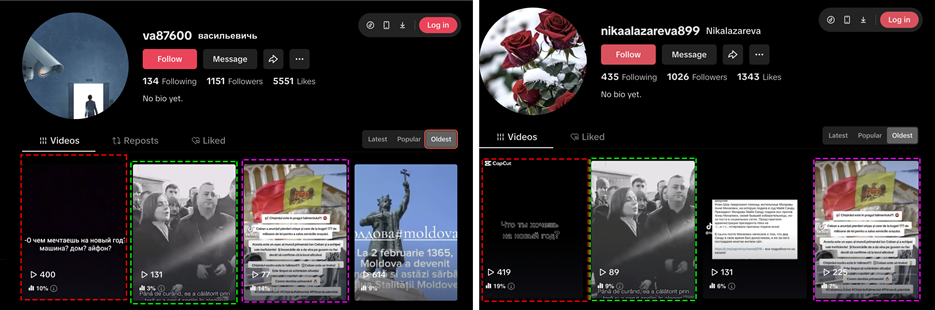

A comparison of two TikTok accounts with nearly identical content posted after their creation. Squared out in red is the New Year’s flashmob, in green is Shor’s message of support to Anna Mihalachi, and in pink are videos targeting Ceban. (Source: @va87600/archive, at left; @nikaalazareva899/archive, at right)

In the later stages of the operation, curators reportedly avoided coordinated hashtags, seemingly to better conceal the inauthentic activity. Instead, they relied on generic tags such as “Moldova” (used 6,849 times in Romanian and 6,151 times in Russian) and “Chisinau” (used 2,922 times in Romanian and 3,337 times in Russian). The third most frequent hashtag, #glasulpoporului (“the voice of the people”), appeared at least 3,180 times. Despite this shift in strategy, the seventh most used hashtag remained “#PAS,” directly targeting Moldova’s ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS). Other hashtags accusing PAS of fraud and corruption also continued to dominate the top twenty most frequently used hashtags. The prevelence of these anti-PAS hashtags aligns with the activity of an earlier anti-Sandu campaign previously reported on by the DFRLab.

Most popular themes

The narratives promoted by the pro-Kremlin operation follow a familiar pattern: attacks on the governing PAS party, allegations of election fraud, claims of betrayal by Western partners, and nostalgic glorification of Soviet and Russian history. The operation also sought to undermine Moldova’s possible European integration by portraying it as a road to instability, war, and loss of sovereignty.

As the elections approached, the network intensified its activity, publishing more anti-PAS content, demanding higher posting frequencies, and pressuring InfoLeaders to fulfill their commitments.

Keyword analysis of video descriptions and text bodies found the network mentioned PAS 7,660 times (26.68 percent of all posts), Maia Sandu 5,578 times (19.43 percent), elections 2,854 times (9.94 percent), and the EU 1,566 times (5.45 percent). Romania appeared in 1,656 posts. The words “war” (1,523 posts), “NATO” (814), and “interference” (433) were also frequent.

The Russian curators had the role of issuing platform-specific posting tasks, often resulting in short bursts of coordinated content on selected topics. Beyond Sandu, the most frequently mentioned figure was Evghenia Gutul, the governor of Gagauzia, who was sentenced in August 2025 to seven years in prison for using Russian funds in her 2023 campaign. She was mentioned in 459 posts, with a notable spike in July, when she first appeared in court, and in August, following her sentencing.

Publications also surged after the European Council sanctioned the Shor-aligned Moldova Mare party and its leader, Victoria Furtună. Another burst followed the Central Electoral Committee’s invalidation of Moldova Mare’s registration, later overturned by the Court of Appeal. In total, Moldova Mare was mentioned 299 times, and Furtună was mentioned 159 times.

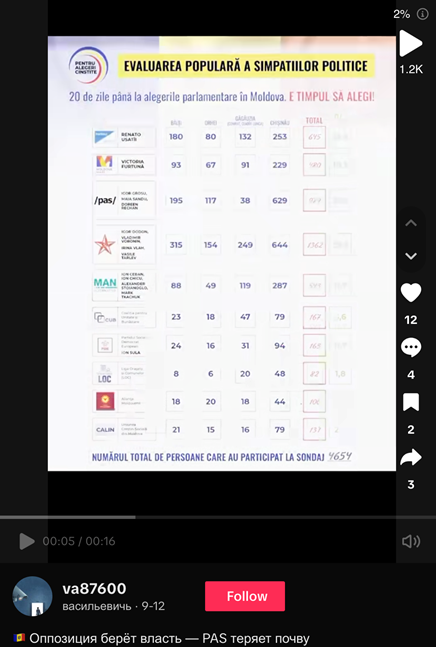

As revealed by the BBC, the network also conducted polls that asked leading questions and embedded misrepresentations into the questions, with the possible goal of being used to dispute election results. The network shared 797 posts that mentioned the words “polls,” another 145 posts mentioned the words “ratings” and “prognosis,” alleging that the PAS party would lose the elections to the opposition. In two instances, an account posted a fake poll issued under the brand “For Honest Elections” (“Pentru Alegeri Cinstite”), an initiative reportedly coordinated by Dimitri Baranovski, a member of Shor’s Evrazia NGO.

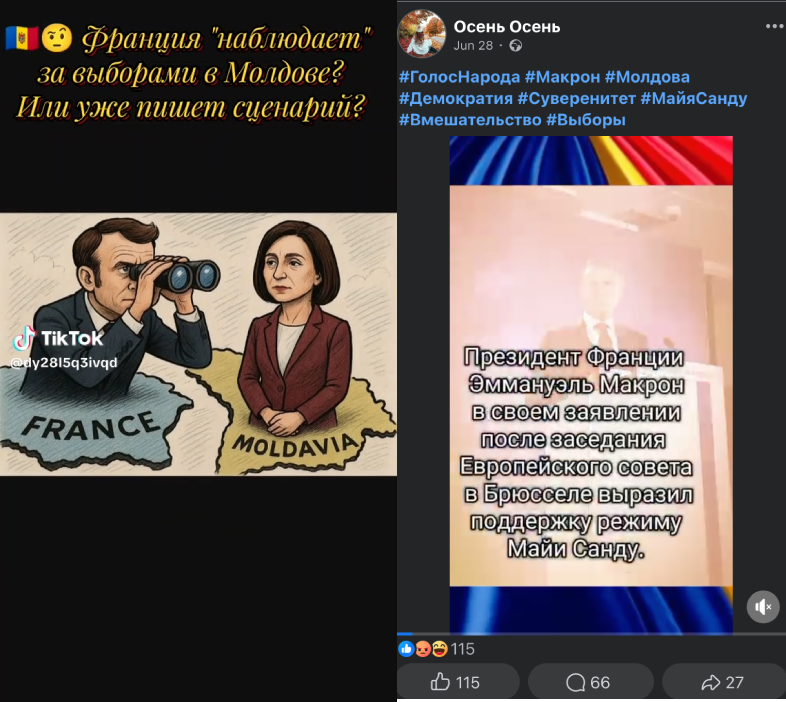

Among the hashtags, the top election-related tags were #elections (#alegeri, #выборы) with 481 occurrences, #elections2025 (#alegeri2025, #выборы2025) with 451 mentions, and #electionsWithoutMacron (#alegerifărămacron, #выборыбезмакрона) with 264 mentions. On multiple occasions, the network spread posts accusing France of interfering in the parliamentary election; 322 posts mentioned France and its president, Emmanuel Macron.

Political linkages and shifting allegiances

The pro-Kremlin operation did not appear to be tied to a single political actor, but instead adapted its messaging to serve the evolving interests of pro-Kremlin actors. Initially, the network was closely associated with the Victory Bloc, the political vehicle of fugitive oligarch Shor. That later changed.

Ahead of the September 2025 elections, and following Moldova’s Central Electoral Commission’s refusal to register several Shor-affiliated parties, at least some of the group members were reassigned to shift their focus from the Victory Bloc to the Moldova Mare Party, led by Furtună, whom they referred to internally as “the new friend” of the operation.

Notably, Furtună had already benefited from the support of Shor’s network during the previous year’s presidential elections. This pivot highlights the network’s flexibility; instead of loyalty to one candidate, it redirected resources to whichever actor seemed most competitive. To facilitate the switch, curators instructed activists to erase traces of the Victory Bloc from their accounts and keep their profiles “clean,” masking the fact that individuals paid to promote the Victory Bloc had pivoted to promoting Moldova Mare. The DFRLab’s analysis found that narratives once tied to the Victory Bloc resurfaced under Moldova Mare, with overlapping language, imagery, and amplification behavior showing the same infrastructure rebranded under a new political flag.

Cite this case study:

Valentin Châtelet and Victoria Olari, “Paid to post: Russia-linked ‘digital army’ seeks to undermine Moldovan election,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), September 24, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/09/23/paid-to-post-russia-linked-digital-army-seeks-to-undermine-moldovan-election/.