Inauthentic Israeli Facebook Assets Target the World

Facebook removed hundreds of inauthentic pages and other assets operated by Israeli political marketing firm Archimedes Group

Inauthentic Israeli Facebook Assets Target the World

BANNER: (Source: @KaranKanishk/DFRLab

Facebook announced on May 16 that it removed a set of 265 Facebook and Instagram assets, including accounts, pages, groups, and events that engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior on the platform.

According to the social media company, some of the assets were linked to Israeli political marketing firm Archimedes Group and targeted audiences around the world, with an emphasis on Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. The tactics employed by Archimedes Group, a private company, closely resemble the types of information warfare tactics often used by governments, and the Kremlin in particular. Unlike government-run information campaigns, however, the DFRLab could not identify any ideological theme across the pages removed, indicating that the activities were profit-driven.

Archimedes Group is an Israeli political marketing firm that claims to run “winning campaigns worldwide,” indicating both the political and global scope of its activities. The company carries out its operations using its product Archimedes Tarva, which, according to an online description, includes “mass social media campaign management and automation tools, large scale platform creation, and unlimited online accounts operation.”

Facebook alerted the DFRLab to a subset of the assets a short time before the takedown. An initial investigation found that a many of them were posting political content to boost or attack local politicians. This was accomplished by creating pages supporting or attacking a politician; pretending to be news organizations or fact-checking organizations; and creating pages designed to provide “leaks” about a given candidate.

The assets showed signs of inauthenticity: some pretended to be from one country but made blatant mistakes in their posts regarding the actual reality on the ground, while others were managed from outside their target country. Likely because of its algorithm, Facebook also identified pages of the cluster as “related pages” when there were no obvious similarities in location or subject matter, suggesting they might be part of the same network.

The network targeted at least 13 countries and were followed by more than 2.8 million users. It is difficult, however, to determine how successful the operation was, since it is hard to know whether the accounts that engaged with these assets were false or authentic. Regardless of the assets’ reach, the fact that they were operated by a for-profit company is a troubling sign that highly partisan disinformation is turning into a capital enterprise.

Targeting the 2019 Nigerian Elections

Many of the pages included in this takedown focused on the February 2019 Nigerian elections that saw Muhammadu Buhari reelected as president of the country.

One of the pages taken down, “Make Nigeria Worse Again,” appeared to be a trolling campaign aimed at Atiku Abubakar, former vice president of Nigeria and Buhari’s main opponent. The page included a banner image of Abubakar as Darth Vader, the notorious Star Wars villain.

The DFRLab also found a highly similar page, “Team Atiku For President,” that aimed at reinforcing support for Abubakar’s presidential campaign. It is unclear why the network carried both a pro and counter operation related to Abubakar, but the supportive page was likely designed to identify his supporters in order to target them with anti-Abubakar content later, possibly diverting them to the “Make Nigeria Worse Again” page.

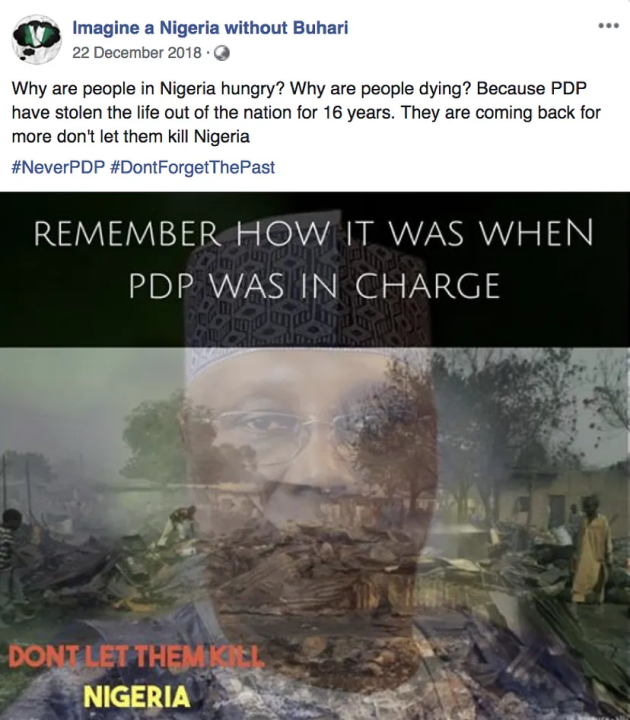

Another page, “Imagine a Nigeria without Buhari,” aimed to bolster support for Buhari’s candidacy. Some of the posts hypothetically eulogized Buhari’s presidential tenure as if he had not been reelected, in order to convince voters of his accomplishments.

Another group of pages focused on the turbulent local election in Nigeria’s Rivers State. The election was held in March, but the announcement of the results was postponed until April because of widespread violence in the region. Several of the removed pages targeted Ezenwo Nyesom Wike, who was running for a second term as governor as a member of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), to which Abubakar also belongs, while others supported his opponent Tonye Cole of the All Progressives Congress (APC) party.

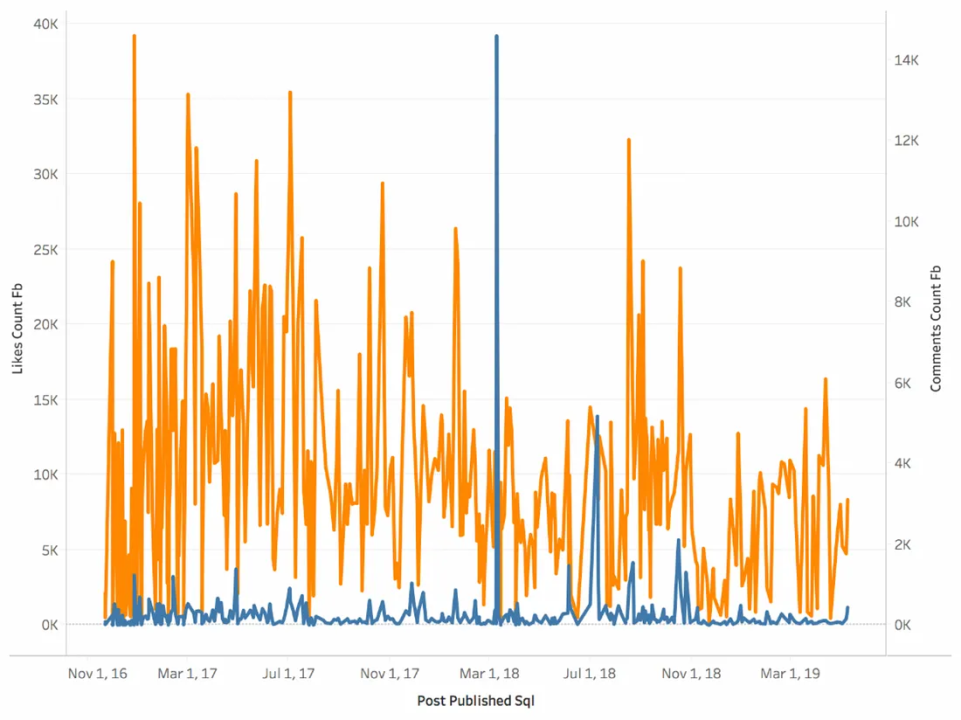

The page “Rivers Violence Watch” described itself as “a platform to report on incidents of violence in Rivers State but nevertheless portrayed a strong anti-Wike and pro-APC bias, suggesting it could have been a part of the same campaign against Wike. Posts from this page had an extremely high share of likes as opposed to comments and shares, one indicator of automated activity.

Fake Fake-Busters, Busted

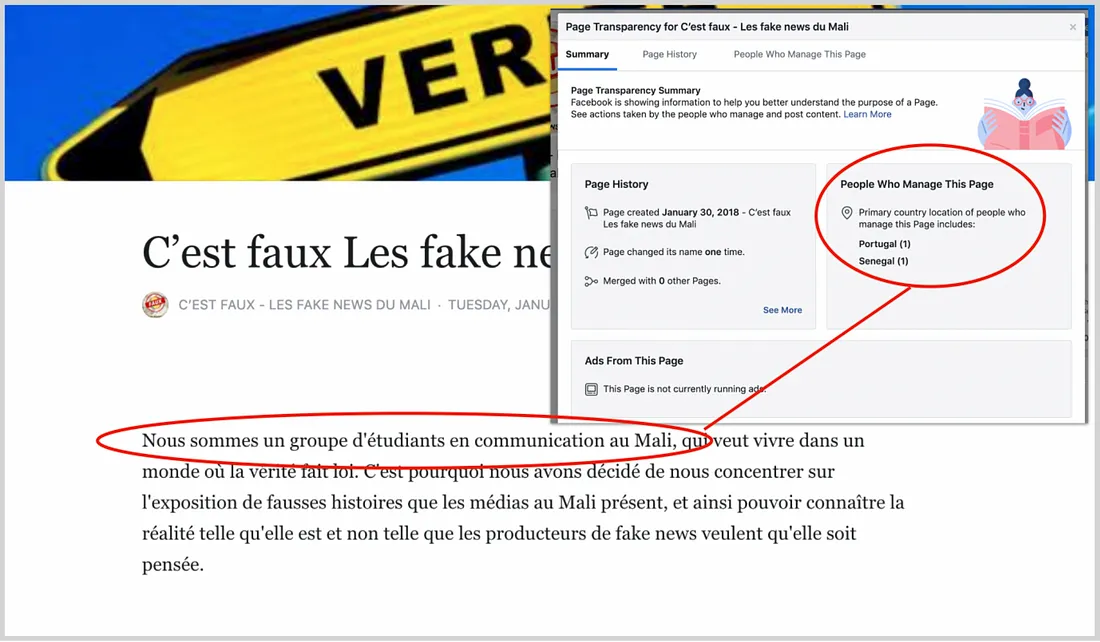

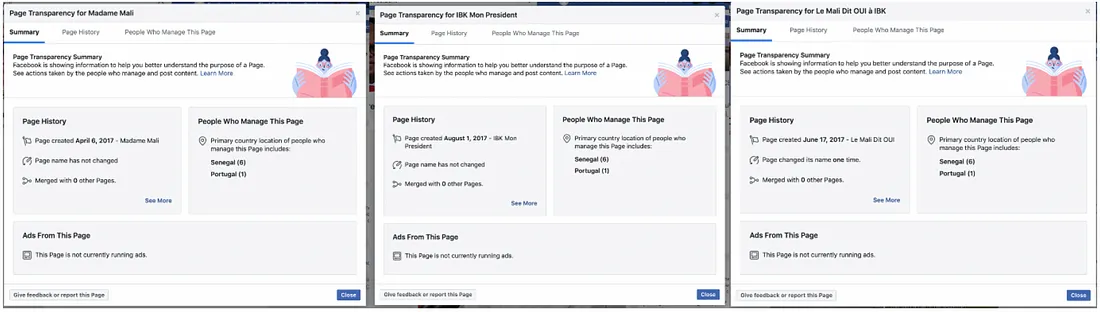

Some of the removed pages posed as disinformation watchdogs, claiming to expose “fake news” in the countries they targeted. For example, “C’est faux — les fake news du Mali” (“It’s false — Mali’s fake news”) claimed to expose “false stories that the Mali media present.” It was created in January 2018 and posted until the end of May that same year.

Most of its posts reported on allegations of “fake news” concerning Africa or targeting Africans. Its “About” section said that it was founded by students of communication in Mali. Facebook’s “Transparency” feature, however, confirmed that it was actually run by managers in Senegal and Portugal.

The focus on fake stories therefore appears likely to have been a front, designed to build a reputation for credibility before running information operations. It was not clear why the page stopped posting in 2018.

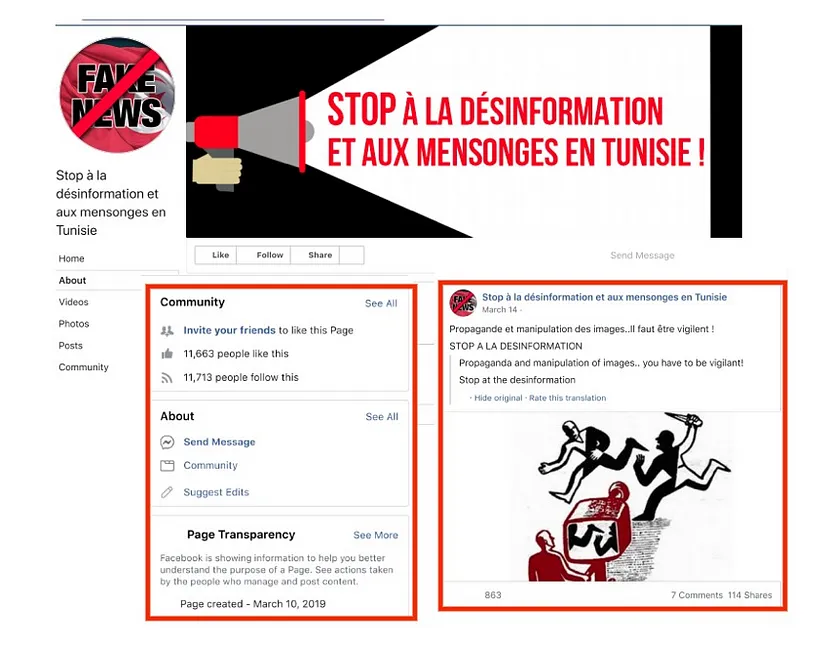

Another page removed by Facebook, “Stop à la désinformation et aux mensonges” (“Stop Disinformation and Lies”), posed as a media watchdog group countering disinformation in Tunisia. Ironically, it focused on calling out what it claimed to be disinformation in Tunisian media, demanding that Tunisians become more vigilant, despite it being an inauthentic disinformation campaign in its own right.

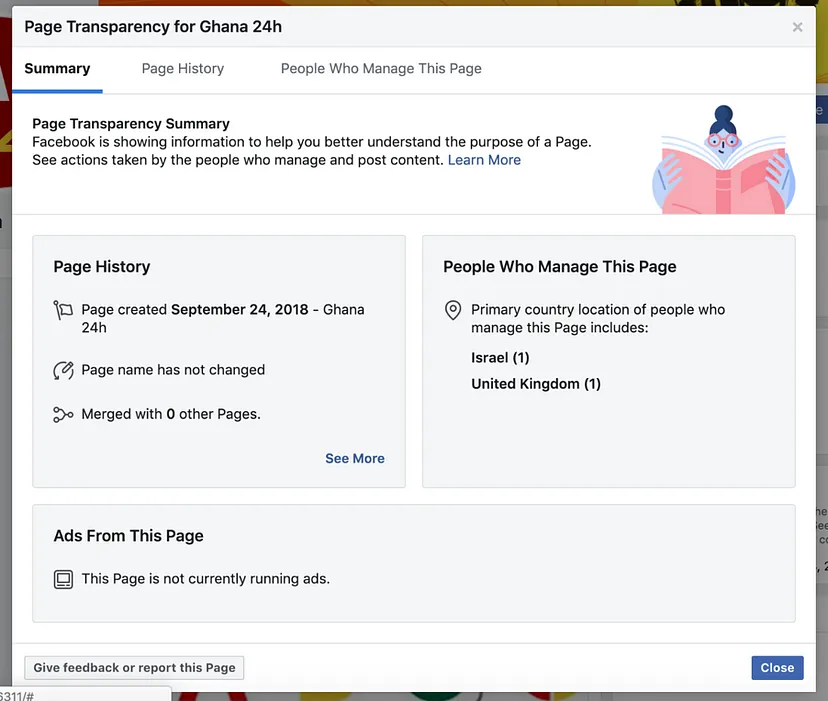

Other pages removed by Facebook claimed to be news outlets. The page Ghana 24, for instance, presented itself as a news site but amplified pro-government stories and news items. Even though the page was about Ghana, it was managed by a user in Israel and another in the United Kingdom.

Many users denounced these so-called “media organizations” in their comments and reviews of the pages, stating that they were spreading “fake news” and disinformation. While writing a review about “The Garden City Gazette,” which also focused on Nigeria’s Rivers State, users said the page was “creating confusion” and “selling fake news.” The comments appeared mostly in February and March, at least two months before the page was taken down by Facebook.

“Leaking” Pages

Some pages in the group promised to deliver “leaked content” that could potentially be weaponized against a candidate or in support of a cause. The page “L’Afrique Cachée,” for example, described itself as organization that specialized in “publishing censored or highly restrained official documents concerning war, espionage, and corruption in Africa.” The page, however, mostly published old news articles accompanied by its own analysis.

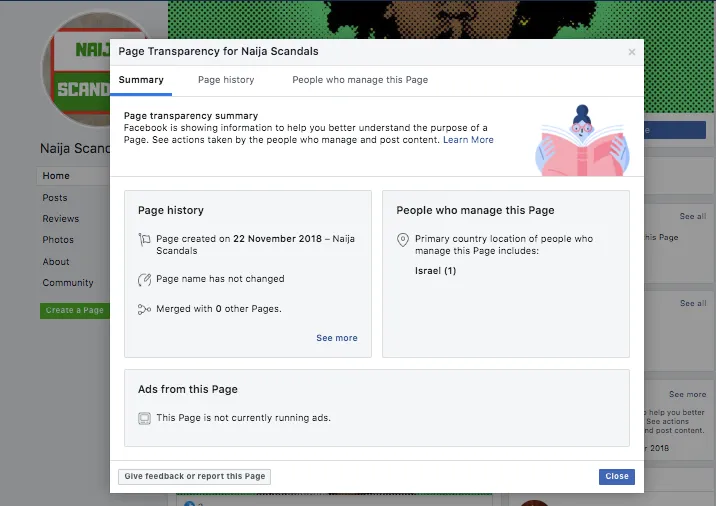

The page “Naija Scandals” (“Nigeria Scandals”), with a page manager in Israel, also described itself as a leak page, promising to share “all the things they would not want you to know about Naija.” Nonetheless, by the time it was taken down this page had no posts — only profile photos that had garnered three to five likes.

Patriots from the Wrong Country

Some of the pages made glaring mistakes that exposed them as likely inauthentic, simply on the grounds of the content.

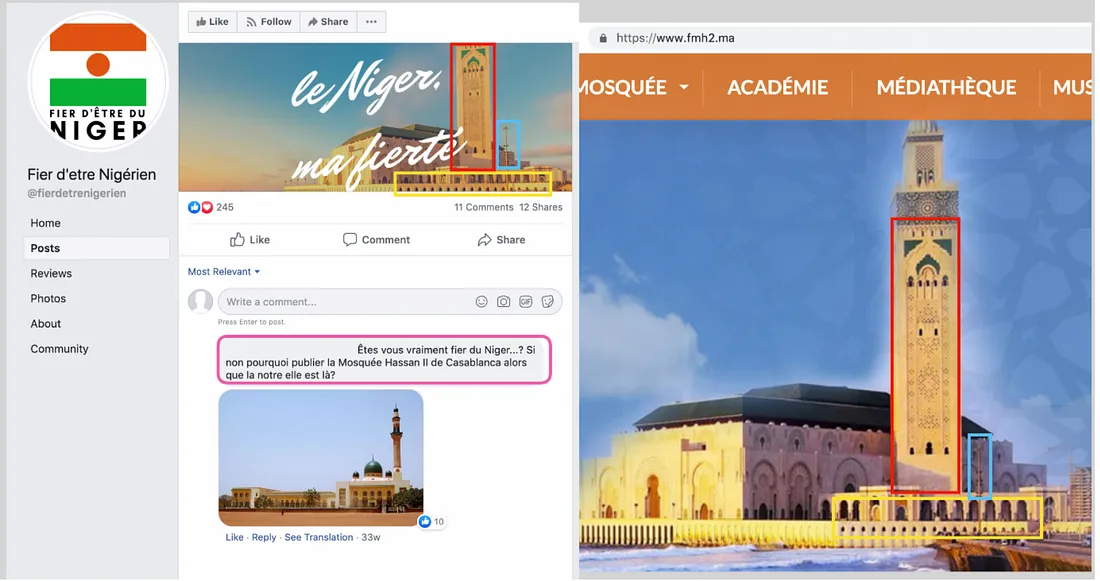

For example, “Fier d’être Nigérien” (“Proud to be from Niger”) struck a highly patriotic tone. Its banner picture featured a mosque, with the caption “Le Niger, ma fierté” (“Niger, my pride”); however, a user pointed out that the mosque was in fact the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, Morocco, which DFRLab confirmed.

Another page, “Tunisie Mon amour,” also featured images of other countries as if they were from Tunisia. The page promoted tourism in the country but used pictures of Morocco and Turkey in its posts.

Location, Location, Location

Many of the pages that focused on individual African countries and claimed to be run by somebody in those countries, were in fact managed from elsewhere. For example, the page “Ghana 24h” purported to be a news site from Ghana, but it was managed by accounts in Israel and the United Kingdom.

Many of the sites that focused on Mali, meanwhile, were in fact run by six managers in Senegal and one manager in Portugal, suggesting that there was a specific regional team behind them. Almost all of these pages supported Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, including pages with names that translated as “IBK, my president” and “Mali says ‘Yes’ to IBK.”

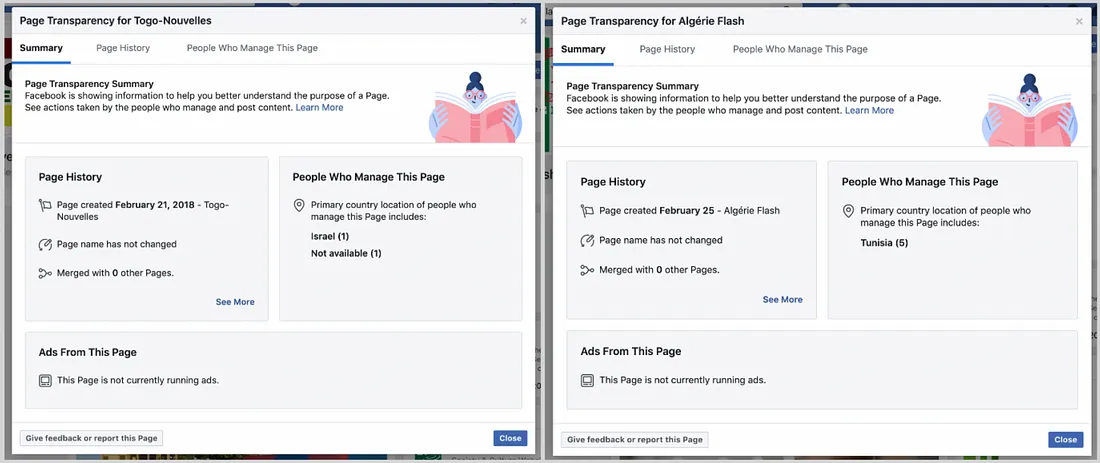

In a similar vein, the page “Algérie-Flash” (Algeria-Flash) was managed from Tunisia, while “Togo-Nouvelles” (Togo-News) was run from Israel and an unknown location.

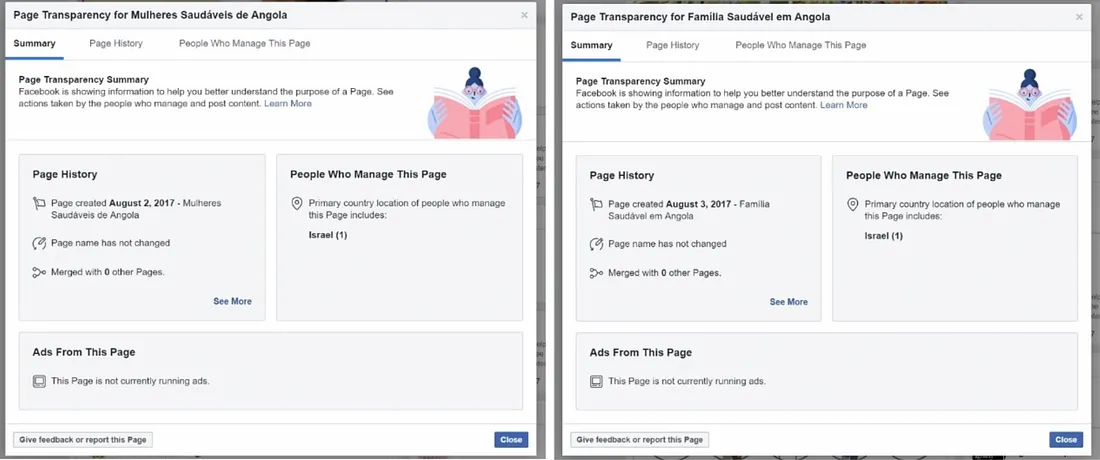

Similarly, two pages dedicated to health issues in Angola named “Mulheres Saudáveis de Angola” (“Healthy Women of Angola”) and “Família Saudável em Angola” (“Healthy Family in Angola”) were managed from Israel.

Related, but Not That Much

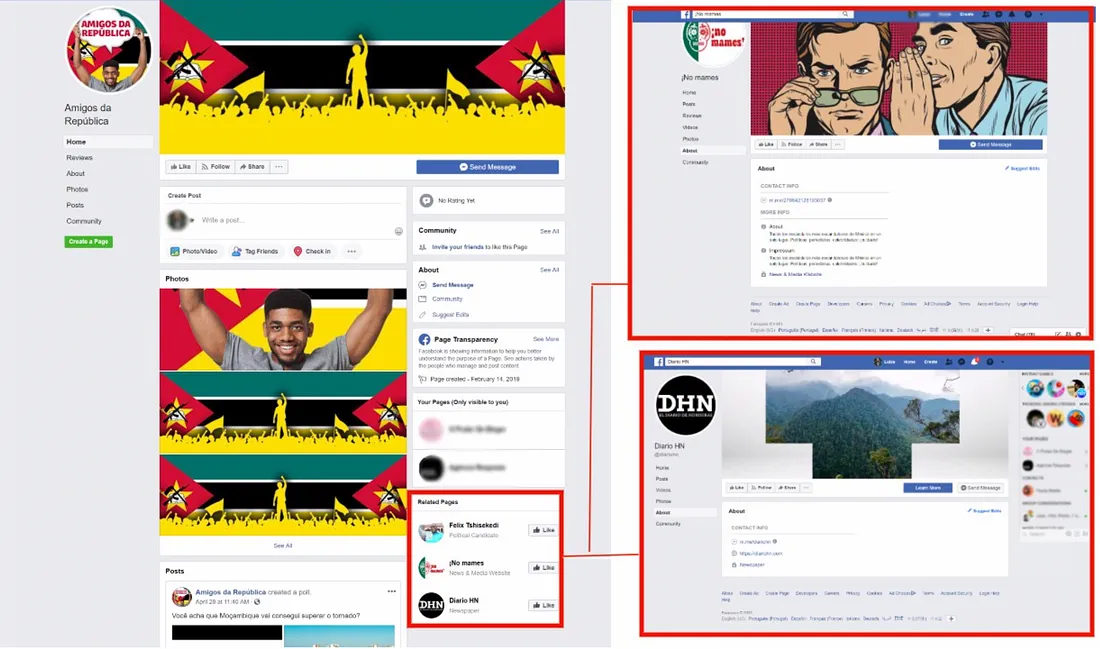

The “related pages” section for some of the removed assets suggested the pages were part of the same network. The “related pages” section is generated by Facebook’s algorithm. While the exact mechanics of the algorithm are not known, it is believed to be based on behavior and relationships of accounts that like, follow, and interact with the pages in question. As Facebook suggested other pages from the removed set as related pages, it indicates that the algorithm recognized a relationship between the accounts.

The most illustrative example of this was the community page “Amigos da República” (“Friends of the Republic”), which was ostensibly from Mozambique. Under its related pages section, Facebook recommended both “No Mames” (“No way!”), a page focused on Mexico, and “DHN,” which focused on Honduras. The pages are not in the same language, not targeting the same continent, and not about the same topic. The only known relationship between them was that they were all ultimately removed by Facebook in this takedown.

Reach and Effectiveness

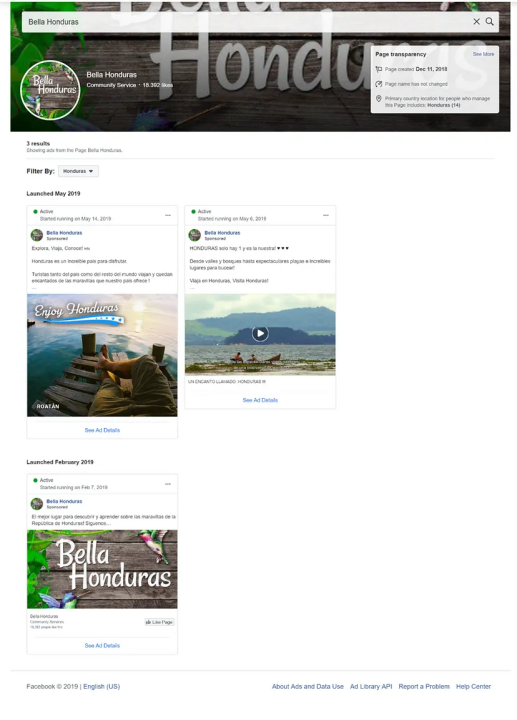

The network of pages taken down by Facebook spent around $812,000 in ad spending paid for in Brazilian reals, Israeli shekels, and U.S. dollars, according to Facebook’s statement. The spending in different currencies suggest how vast the operation was, encompassing multiple regions around the world.

The DFRLab analyzed the page with the highest number of followers, “Peuple du Mali,” which targeted local politics in Mali, and found that it had very high likes in comparison to comments. When this type of discrepancy is spread across many posts, the engagement should be considered suspicious.

It is unclear whether other pages also had inorganic engagement, but Facebook’s statement highlights that many of the accounts were considered inauthentic because of inflated and manipulated engagement.

Mohamed Kassab is a Digital Forensic Research Assistant with @DFRLab based in Cairo.

Register for the DFRLab’s upcoming 360/OS summit, to be held in London on June 20–21. Join us for two days of interactive sessions and join a growing network of #DigitalSherlocks fighting for facts worldwide!