Anonymous pro-government Twitter accounts deny allegations of a crisis in Zimbabwe

Accounts amplified narratives that the U.S.

Anonymous pro-government Twitter accounts deny allegations of a crisis in Zimbabwe

Accounts amplified narratives that the U.S. instigated Zimbabwe smear campaign

Following the arrest of Zimbabwean investigative journalist Hopewell Chin’ono, anonymous Twitter accounts worked to deny allegations of an economic, healthcare and human rights crisis taking place in Zimbabwe against the backdrop of the viral anti-government hashtag #ZimbabweanLivesMatter. The accounts amplified unsubstantiated claims that the United States had orchestrated a smear campaign against Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe’s ruling party, Zanu PF, and President Emmerson Mnangagwa have repeatedly blamed the country’s crumbling economy, government corruption and food shortages on U.S. sanctions, a claim that regularly plays out on social media. Social media platforms became political battlegrounds during the Robert Mugabe era, given the dangers of protesting in public as a result of government crackdowns and police brutality.

On July 20, 2020, Chin’ono livestreamed police entering his home and arresting him, before his social media accounts were deleted. Chin’ono was charged with inciting public violence after encouraging his Twitter followers to join an anti-government march set for July 31 to protest state corruption. Jacob Ngarivhume, the leader of a small opposition party, was also arrested for allegedly planning the July 31 march. The Zimbabwean government was criticized for its “total intolerance of criticism” after several human rights activists and scores of protestors were arrested on July 31.

Chin’ono and Ngarivhume are not the first Zimbabweans to be arrested over political content posted to social media. In 2016, authorities arrested a pastor named Evan Mawarire and charged him with treason after he started an anti-Mugabe movement under the hashtag #ThisFlag. (The charges against Mawarire were later dropped.) Similarly, the leader of the #Tajamuka/Sesijikile campaign, a more politically active and organized pressure group that campaigned against Mugabe’s rule, was also arrested for calling for nationwide protests. The arresting of journalists and protesters, a common tactic used to quash dissent under the Mugabe era, was regularly extended to include social media users.

The Zimbabwean government has received both local and international condemnation over the arrests of Chin’ono and Ngarivhume, as well as allegations of human rights abuses in the country. In an August 4 televised address, President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who effectively thwarted the protests by enforcing curfews and increasing police and military presence, promised to overcome the attempts of “rogue Zimbabweans acting in league with foreign detractors” to destabilize the country.

Despite pressure from the international community, pro-Zanu PF Twitter accounts actively claimed that no human rights abuses occurred in the country. These accounts, some allegedly operated by high-ranking government officials, worked to prove that the United States was orchestrating a smear campaign against Zimbabwe.

Blaming the U.S.

Ahead of the 2018 elections, Mnangagwa told Zanu PF youth members to go online and “dominate” the Zimbabwean social media environment. This network of vigilant, pro-Mnangagwa accounts that troll social media platforms are known as Varakashi, or “destroyers,” after Mnangagwe himself claimed online chat rooms were war rooms.

According to the human rights advocacy group Advox Global Voices, the Varakashi’s role is to push the narrative that anyone who criticizes the Zimbabwean government is an unpatriotic agent of foreign powers, a job that allegedly pays USD $80 per month.

After Chin’ono’s arrest, a group of accounts set out to claim that he was working with the U.S. government, particularly its embassy in Harare. These accounts claimed Chin’ono was not a journalist but instead provocateur paid by the U.S. to destabilize Zimbabwe.

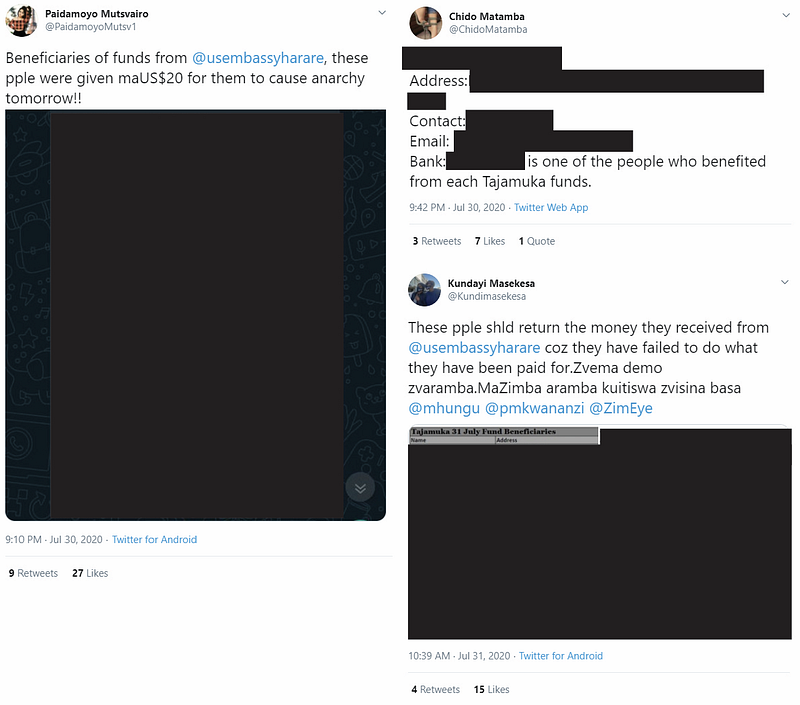

Some accounts also attempted to delegitimize the protests before they took place by claiming participants were being paid to demonstrate. On July 30, the day before planned protests, a number of accounts posted lists containing the names, addresses, and contact information of people they claimed were being paid by the United States to “cause anarchy.” Other accounts reposted the same lists on July 31, after any significant protests had been quashed the Zimbabwean armed forces, claiming the listed individuals should pay back the United States for failing to cause any serious disruptions.

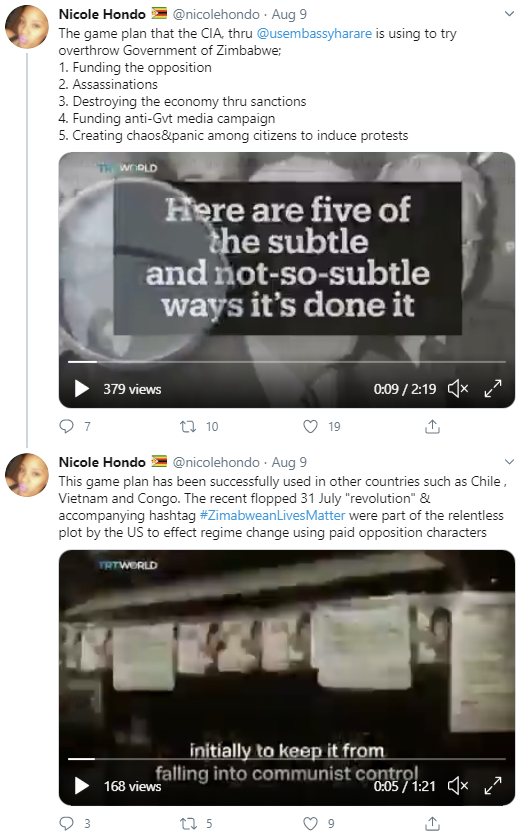

Other accounts, such as the anonymous @nicolehondo, claimed the United States wanted to overthrow the Zimbabwean government rather than simply destabilize it. The account claimed the viral #ZimbabweanLivesMatter was orchestrated by the U.S. after the country paid for “opposition characters” to create chaos and panic. At the time of research, @nicolehondo had been temporarily restricted for over a week. By September 1, 2020 the account had been suspended.

An article published be Zimbabwe’s state-owned daily newspaper, The Herald, accused Chin’ono, Ngarivhume, and other opposition leaders of being “inciters” likely being paid by the United States. The Herald has previously published articles by other popular Twitter accounts, such as Nicole Hondo, criticizing U.S. and European interference in Zimbabwean politics.

“There is no crisis in Zimbabwe”

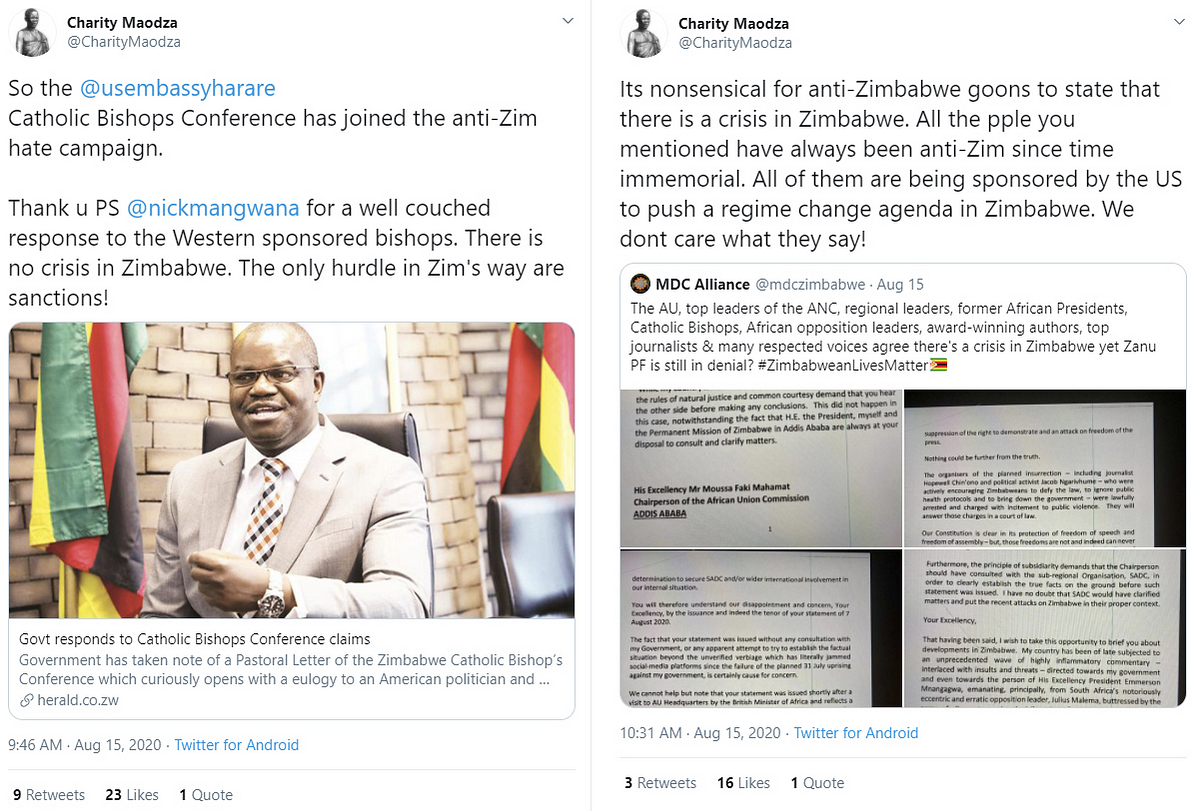

A press release dated August 6 and signed by Zimbabwean Secretary for Information, Publicity, and Broadcasting Services Nick Mangwana claimed allegations of a “crisis” in Zimbabwe were false. Mangwana insisted that misinformed individuals, political activists, and global actors were behind a “smear campaign.” He also dismissed a letter by the Zimbabwe Catholic Bishop’s Conference calling for urgent reform, accusing the religious organization of joining forces with Zanu PF detractors to “manufacture crisis.”

The claim that there was no crisis in Zimbabwe was subsequently amplified by accounts that previously claimed Chin’ono was a foreign agent. An account called @CharityMaodza, which had over 10,000 followers, combined the crisis and foreign intervention narratives. It claimed the Roman Catholic Bishop’s Conference was sponsored by the United States and thus told to join the “anti-Zim campaign,” and that there was no crisis in Zimbabwe.

On August 7, Twitter account @Jamwanda2 posted an image of a soldier about to beat a woman, claiming it had been badly photoshopped in an attempt to prove the lie that there was a crisis in Zimbabwe.

However, the Facebook page for NewsDay Zimbabwe, an independent daily newspaper, published a series of images later that day as evidence that the image was, in fact, legitimate and had not been edited in any way. Fact-checking organization ZimFact also corroborated the image’s legitimacy.

Government ghost accounts

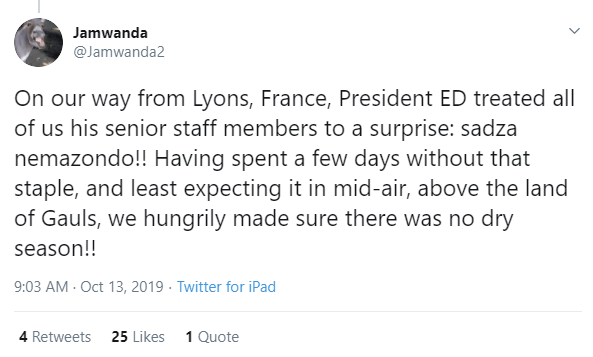

Several high-ranking government officials have been accused of operating ghost accounts. One prominent pro-government account is @Jamwanda2, which ZimFact reported was operated by Presidential Press Secretary George Charamba. Although the account, which has over 33,000 followers, operates anonymously, the DFRLab found tweeted evidence of the account operator claiming to be Charamba. On October 13, 2019, the account posted original images of Mnangagwa in his private airplane, while also identifying itself as a senior staff member in a series of tweets.

Then on November 28, 2019, the account posted merit certificates for a child named Mukudzei Charamba, telling Twitter users to figure out the connection between Mkudzei and the Jamwanda profile. The DFRLab used reverse image searches to try and identify if the certificates had been posted to other platforms before being posted by @Jamwanda2 but could not find any evidence to indicate the images were not original content.

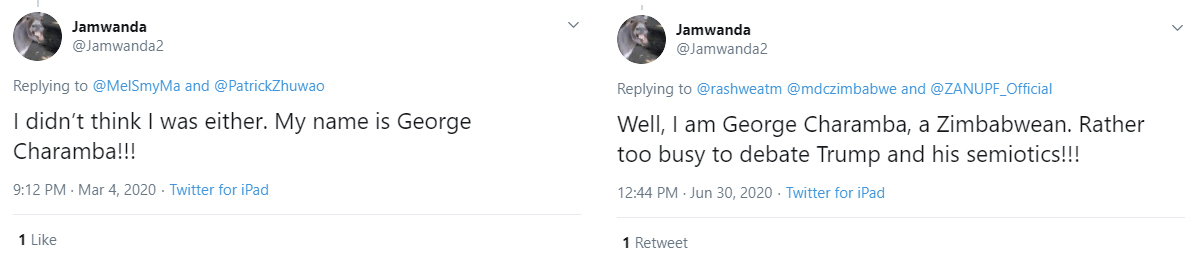

Although the account subsequently denied it was operated by George Charamba in the responses to the certificate posts, on March 4 and June 30, 2020, it contradicted itself and claimed to belong to Charamba.

Most recently, Zimbabwean Secretary for Information Nick Mangwana was accused of operating pro-Zanu PF accounts @nicolehondo and @CharityMaodza. Mangwana denied operating either account.

The @CharityMaodza and @nicolehondo accounts regularly post very similar content within minutes of each other. On August 11, the accounts posted the same image of a person wearing shoes in bed — one image rotated 180 degrees — within two minutes of each other. The DFRLab performed a reverse image search on the picture and found it had originally been posted by a prominent Zimbabwean account in 2018, then reposted by another suspected Varakashi member in May 2020.

Mangwana’s official account, @nickmangwana, regularly engaged with both accounts, and in certain instances all three would post similar content. Mangwana also referred to Charity Maodza and Nicole Hondo as his sisters after all three personalities wrote articles published by The Herald.

After the @nicolehondo account was temporarily restricted and subsequently suspended by Twitter, Mangwana started to share content from another account, @nicolehondo_. The account was created on March 26, 2020 and appears to have been created as a backup for the first account.

Despite continued attempts by anonymous Twitter accounts to deny allegations of a crisis in the country, #ZimbabweanLivesMatter has remained trending on Zimbabwean Twitter for over a month.

Tessa Knight is a Research Assistant, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in South Africa.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Additional information provided by Sean Ndlovu, co-founder and Innovation and Research Manager of CITE

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.