South Africa social media users stoke racial tensions ahead of bail hearing of murder suspects

Left and right-aligned accounts posted threats

South Africa social media users stoke racial tensions ahead of bail hearing of murder suspects

Left and right-aligned accounts posted threats of violence and images of weaponry ahead of the emotionally charged hearing

Ahead of the scheduled bail hearing of two men accused of murdering 21-year-old farm manager Brendin Horner, South African social media users from both sides of the political spectrum posted images of firearms and enflamed racial tensions. Activists protesting farm murders and farm attacks, as well as members of the third-largest political party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), faced off online ahead of the October 16 bail hearing for the two men accused of murdering Horner in the small town of Senekal in South Africa’s Free State.

Farm murders and attacks are not classified as their own specific category of crime in South Africa, rather falling under general homicide or assault. This has resulted in large discrepancies in reported numbers of attacks — numbers that are almost impossible to calculate, according to Africa Check. Despite this, false narratives around farm attacks have reached an international audience. President Cyril Ramaphosa issued a statement claiming the belief that farm violence is a coordinated campaign orchestrated by black South Africans to drive white farmers from their land is patently false. However, the narrative of farm attacks and murders frequently morphs into claims of white genocide or ethnic cleansing of white communities, claims that are propped up by misleading information about farm attacks.

During the first court appearance of the two men accused of murdering Horner, a group of farmers and activists demonstrated against farm murders outside of the courthouse. A local resident named Andre Pienaar was later charged with attempted murder, incitement to violence and public violence after he allegedly encouraged a group of protesters to storm the Magistrate’s Court.

The EFF decided to demonstrate in Senekal to allegedly protect state property against white protesters, according to EFF leader Julius Malema. On October 16, white farmers and black members of the EFF faced off outside the small-town courthouse, separated by barbed wire with over 100 police patrolling the area as the two men accused of murdering Horner appeared in court.

Right-wing posts on Telegram

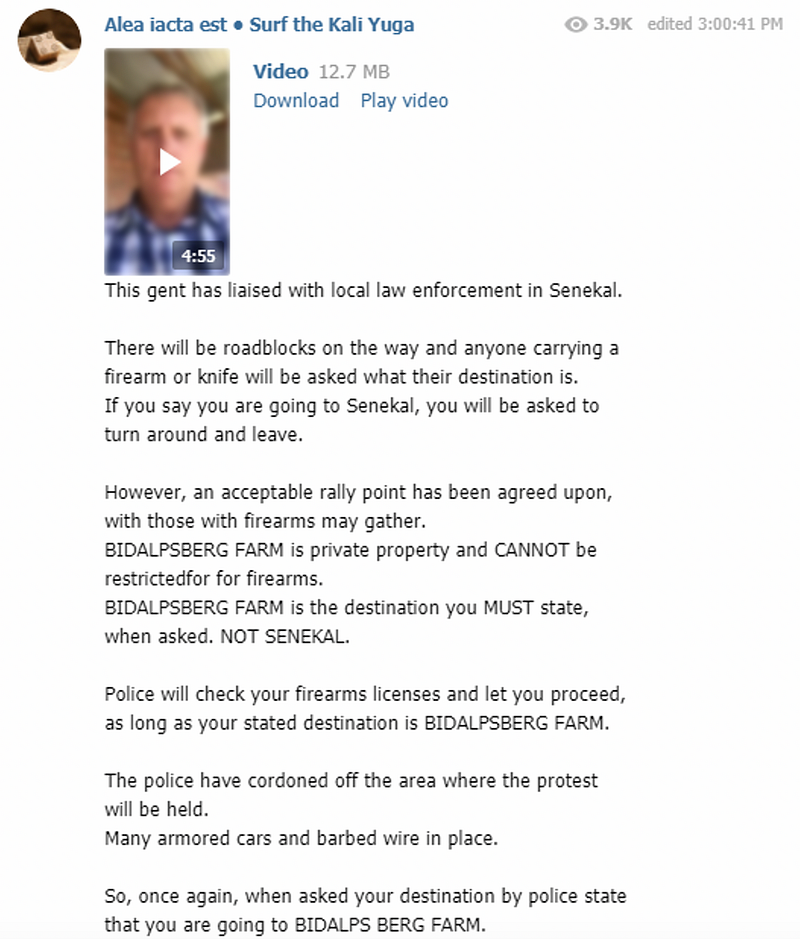

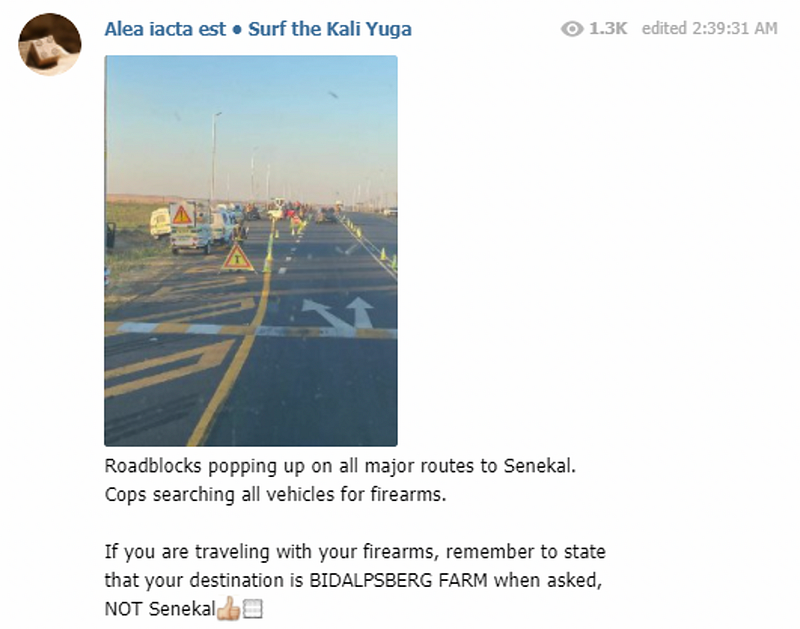

A message telling farm murder protesters how to avoid having their weapons confiscated by police was originally posted to a Telegram channel dedicated to “redpilled news” from South Africa, but quickly spread to other right-wing Telegram channels.

The channel emphasized that protesters carrying firearms should not tell law enforcement their intended destination throughout the day of October 16. According to the Regulation of Gatherings Act of 1993, it is illegal for a participant at a gathering or demonstration to have a firearm, imitation firearm, or dangerous weapon in their possession.

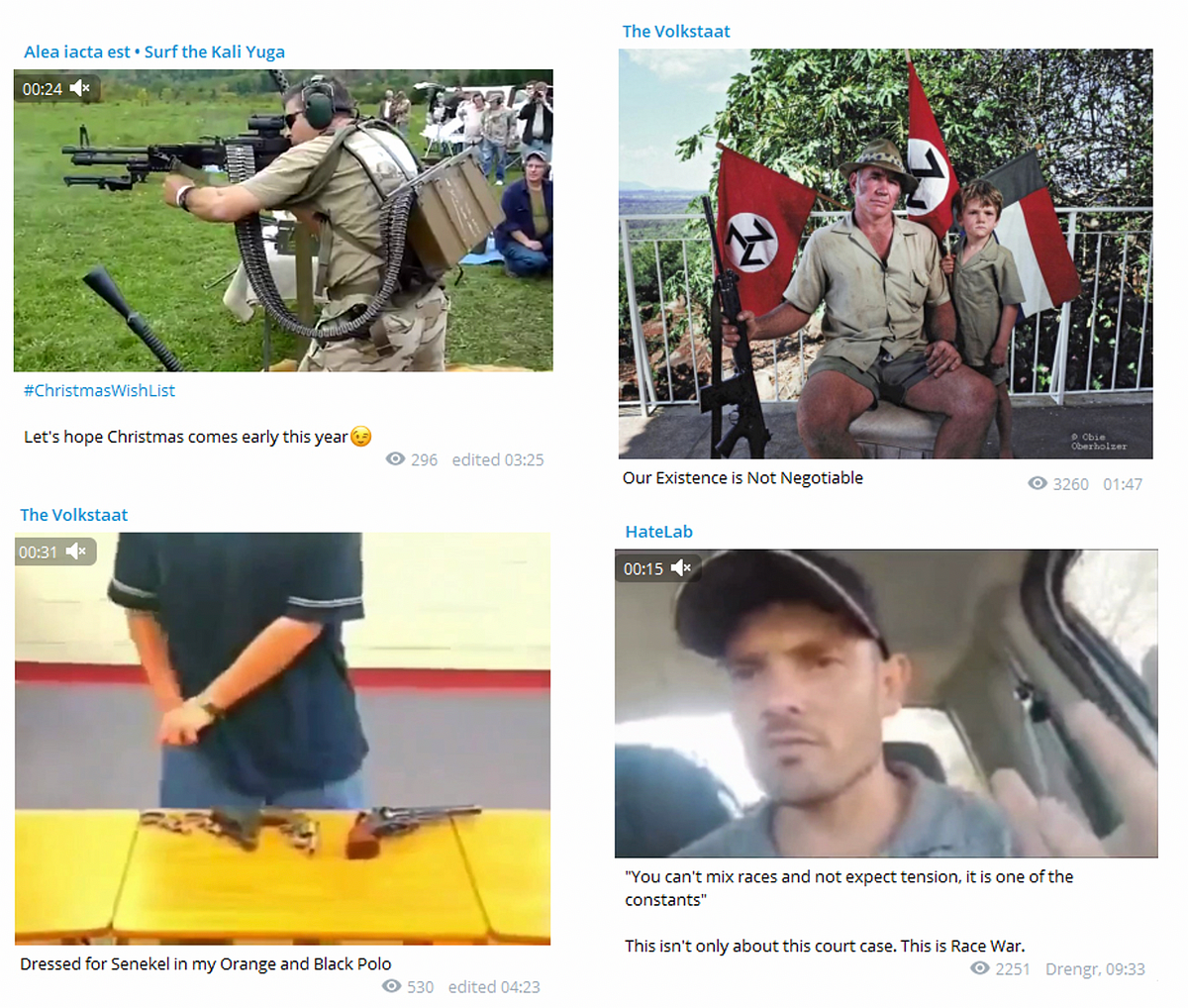

Other posts from different far-right channels posted images of weapons and calls to arms. The channels also frequently posted racist and derogatory content on the days leading up to the protest.

A small channel was also created a few days before the protest, for those going to Senekal to offer transportation to anyone else interested in attending the demonstration. Despite being advertised across a number of activist right-wing channels, the group had less than 100 members and did not appear to have much impact on the protest itself. After the October 16 protest, the channel changed its name to Remember Senekal.

The left on Twitter

Members of the EFF primarily took to Twitter, and Facebook to a lesser extent, to express their opinions on the Brendin Horner case and the scheduled protests. On October 6, the first day the two men accused of Horner’s murder appeared in court and activists stormed the building, EFF parliamentary member Nazier Paulsen posted an image of himself in a gun shop, holding an assault rifle with the caption, “Get ready!” A day later EFF leader Julius Malema told EFF members to attack.

Four days later, Malema posted a picture of a machine gun to his Twitter account, alongside a confused emoji. The country’s opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), laid criminal charges against Malema for the tweet, claiming it amounted to a “reckless attempt by the EFF leadership to further violence.”

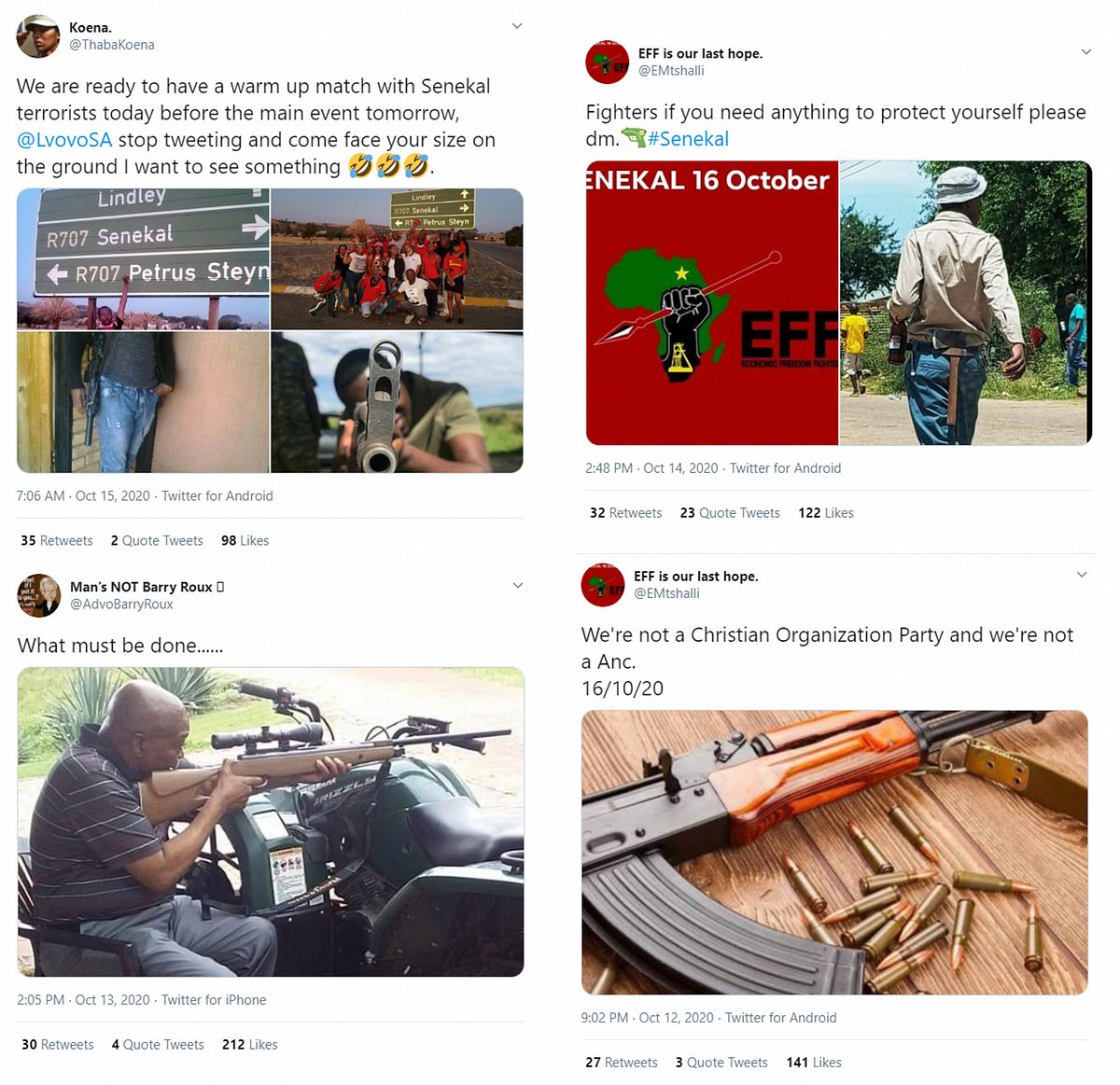

But other EFF party members followed Malema’s example, and in the days leading up to the October 16 protest EFF social media users posted images of weapons to social media, even asking their comrades, or fellow members, if they needed to be supplied with weaponry.

While EFF protesters appeared to primarily post on Twitter, a number of farm murder protesters also used the social media platform to post images of weapons. Some users also threatened violence against Malema himself.

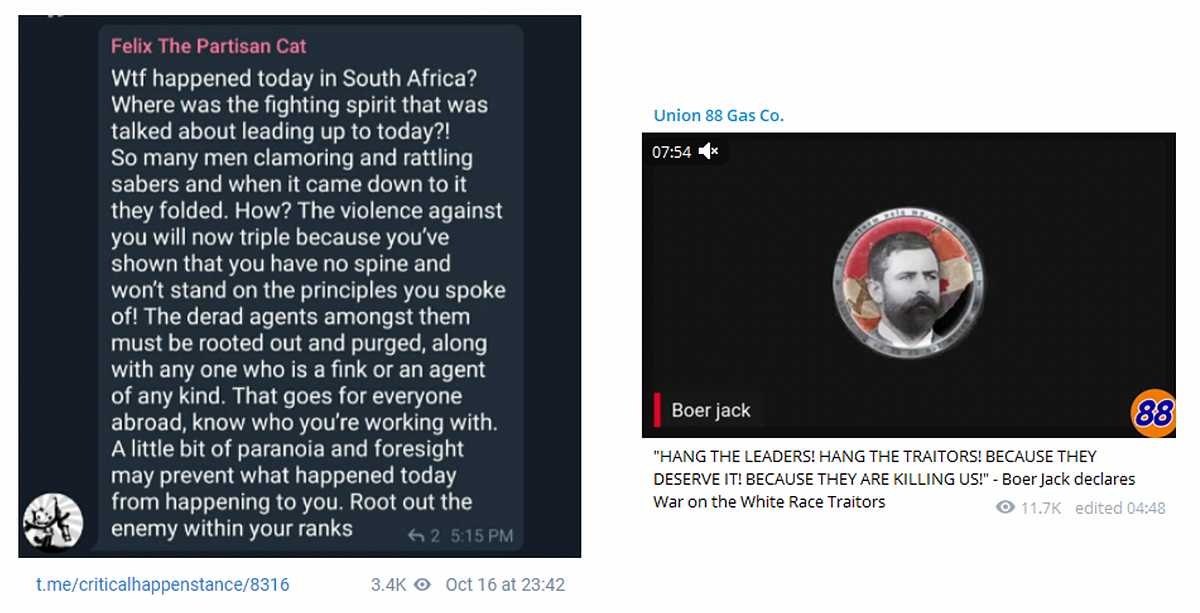

Lamenting the lack of violence

After the protests died down on October 16, a number of Telegram channels circulated messages expressing disappointment at the lack of violence. One post, which had nearly 12,000 views, claimed the group’s leaders had betrayed their cause and made the farm murder protesters appear weak to the EFF, their “enemy.” Others indicated there needed to be retaliation for EFF members singing “shoot the boer,” a song that was criminally banned over a decade ago. A complaint has subsequently been laid with the South African Human Rights Commission over the song.

Comments and posts on anti-farm murder Telegram channels were divided among those who believed the protest should have been more militant, and those who believed the protestors were correct to maintain order. However, posts calling the leaders “traitors” garnered more attention than those calling the day a victory.

Conversely, after the protest, the official EFF Twitter account posted a statement congratulating its members on a successful protest. The statement included appreciation for the protesters’ “utmost discipline in the face of provocative racists,” but did not mention the fact that EFF members threw stones at farmers at one point during the protest.

However, despite claims that both EFF and anti-farm murder protesters would bring firearms to the October 16 protests, only one person was arrested for carrying an illegal firearm. As President Ramaphosa stated, old apartheid wounds were opened, but the scene did not descend into the all-out race war both sides attempted to incite before meeting in the small town.

Tessa Knight is a Research Assistant, Southern Africa, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab) and is based in South Africa.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.