When accurate coronavirus info grows stale, obsolete data becomes misinformation

Social media channels and fringe outlets

When accurate coronavirus info grows stale, obsolete data becomes misinformation

Social media channels and fringe outlets rehash old stories from Bulgaria and Ukraine, implying prior COVID-19 data still accurate

Facebook groups and fringe media shared obsolete COVID-19 articles with Internet users in Ukraine, Russia and Kyrgyzstan, misleadingly diminishing the danger of the pandemic.

Despite consistent fact-checking efforts worldwide, coronavirus-related narratives are awash with disinformation and rumors alongside large amounts real data, leading to what the World Health Organization is referring to as an infodemic. Given the rapidly changing nature of the pandemic, however, even valid data might be misused simply by being published or amplified several days or weeks after its initial release date. Once-accurate information can become misinformation as it ages, leading to erroneous conclusions and misinterpretation of the current situation.

The lottery articles

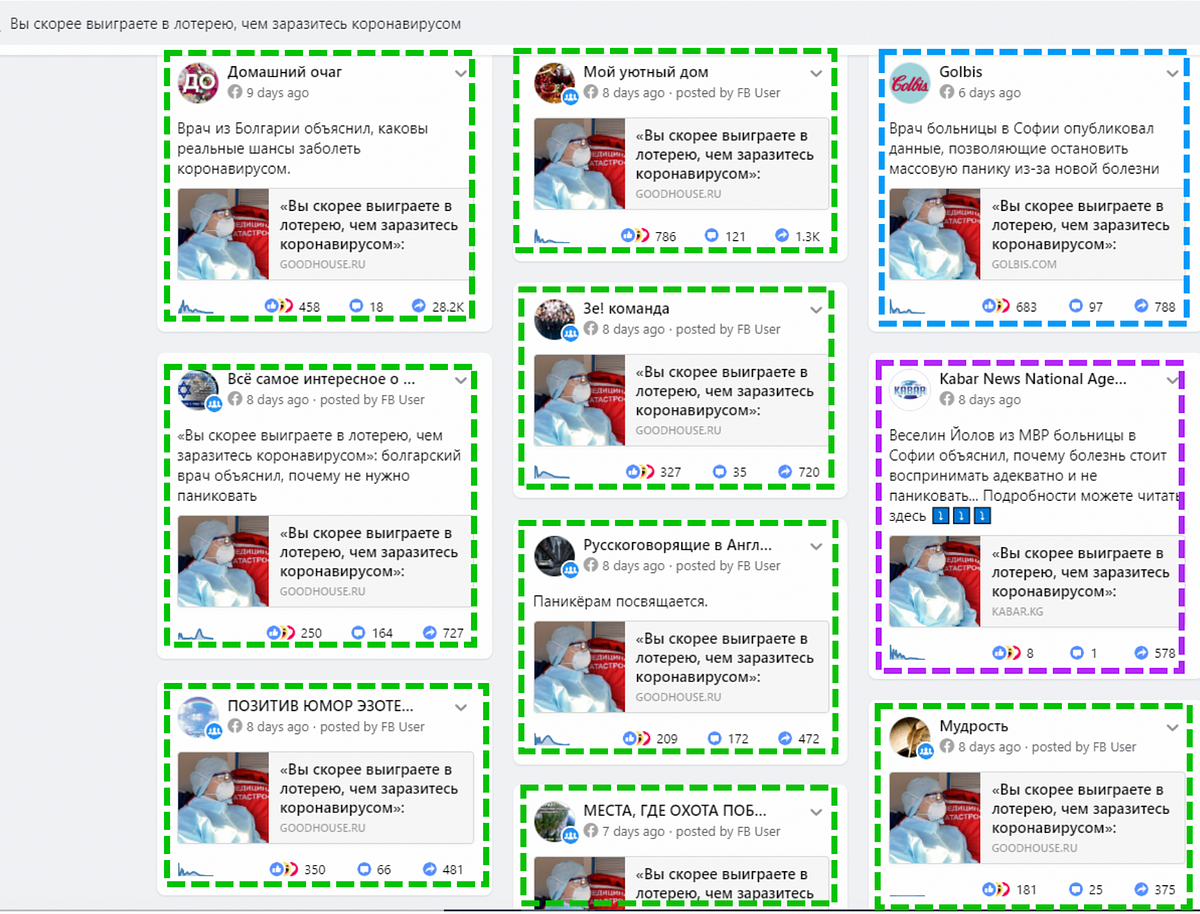

In the middle of March 2020, multiple websites began sharing an article called “You are more likely to win the lottery than getting coronavirus.” The story was based on a now-deleted Facebook post of Veso Yolov, a Bulgarian doctor from the Medical Institute of Ministry of Internal Affairs. Mr. Yolov allegedly claimed that most COVID-19 cases were occurring in China and that the mortality rate for people younger than 50 is so low so that it is easier to win the lottery than die from it if you had not visited China. Moreover, the article provided mortality statistics from February 10 as “one of the worst days for now,” with 108 COVID-related deaths in China, comparing the stats favorably to mortality rates from other situations like cancer, heart disease, and even insect bites.

While the date of the now-deleted Facebook post is unclear, the articles citing it appeared in Bulgaria on March 10 and in Russian media on March 11, giving the post’s publication date as ranging somewhere between February 10 and March 10. The author provided data suggesting that around 100,000 people were sick at the moment, which according to Johns Hopkins tracking data, potentially narrowing down the publication date to approximately March 3–4, when the official tally surpassed 100,000 positive cases. However, if the article was written in early March, it ignored that fact that several other days since February 10 had actually been worse, including 158 people dying on February 23.

The post also began to circulate on fringe media and social media. The main spreader of this news in the Russian language was GoodHouse.ru, which published it on March 11; at the time of publishing, this article had been shared on Facebook 57,443 times. At the same time, other sources like aggregator golbis.com, fringe media from-ua.info, and Kyrgyz National News Agency Kabar.kg republished the article.

The part of the article citing the February 10 mortality rate was recycled and used in several other publications on Facebook, despite the fact it was old data. It was featured in a March 9 post by Roman Goldman, director of a clinic in Israel, and in a March 12 post of Ukrainian blogger Eugene Sereda. The latter received 19,000 shares, while the former received less than 1,000 shares but gained its audience in Telegram and on fringe media like the Russian-language My Homeland.

Several Telegram channels regurgitated Goldman’s post, citing it and the February 10 mortality data. According to the Telegram analytics tool TGStat, the post was published by Divannyy Analytic (8,298 members), Yevheniy Chernyak (6,919 members), and TheAmanbayev’s Mood (3,621 members).

The Ukrainian TV host’s Instagram post

In mid-March 2020, another old story started to gain wide dissemination in Ukraine. On January 29, Ukrainian TV travel show host Dmitriy Komarov wrote a note on his Instagram passing along a message from Chinese colleagues that COVID-19 is not that different from the flu, and that the probability of this virus to appear in Ukraine was extremely low. The post received 115,269 likes and appeared during a time when the virus had yet to spread in in Ukraine or nearby countries. A week later, the Instagram publication was recycled by fringe media UkrLife, which was 176 engagements from groups or pages at the time. However, by mid-March, this publication received 45,275 shares and became the top Ukrainian-language publication referencing coronavirus in a headline, according to the social media listening tool BuzzSumo.

The original post, of course, is not disinformation per se, as it was accurate for the time in which it was written. However, it received an enormous boost in Facebook groups and became viral in March, more than a month after it was written, by which time COVID-19 cases had been confirmed in Ukraine as well. It received significant boosts in Ukrainian Facebook groups with large audiences as recently as March 6, including ones focusing on humorous videos and others dedicated to residents of different Ukrainian cities.

These two cases are classic examples of a specific type of misinformation that occurs when people share information that was once accurate but has become out-of-date. During a pandemic, though, such misinformation could lead to underestimation of the danger and careless behavior by readers, further deteriorating an already tough situation.

Roman Osadchuk is a Research Assistant with the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab).

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.