How Bolsonaro’s disinfo machine targeted Brazil’s pro-quarantine health minister

Online defamation campaign besieged Luiz Henrique

How Bolsonaro’s disinfo machine targeted Brazil’s pro-quarantine health minister

Online defamation campaign besieged Luiz Henrique Mandetta prior to his April 16 firing

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who has routinely dismissed the seriousness of the COVID-19 pandemic, fired Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta on April 16 after an escalation of tensions that started when the minister called for social distancing measures in the country. The removal of Mandetta was preceded by a defamatory campaign, in part amplified by the president himself, that included false and misleading information and unfolded in different platforms, ranging from hyper-partisan websites to WhatsApp.

The successful implementation of this disinformation campaign shows how President Bolsonaro’s allies have managed to foster an alternative information ecosystem in Brazil. Since the right-wing politician came into office in 2019, political rivals, journalists, and former allies have frequently been the targets of attacks by large groups of pro-Bolsonaro supporters for criticizing the president. These aggressions originate primarily from hyper-partisan media, influencers, Twitter trolls, and WhatsApp operators, forming what is essentially a pro-Bolsonaro disinformation machine.

Former allies of the president claim the government runs an information operation known as the “hatred cabinet.” Members of this cabinet, including the president’s sons, have been accused of disseminating hate and disinformation on social media. Brazil’s Congress has created a dedicated parliamentary commission to investigate the claims.

At the time of publishing, Brazil had experienced more than 2,500 deaths and 40,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19. Yet President Bolsonaro is one of only a handful of world leaders that continues to downplay the seriousness of the novel coronavirus. The president claimed COVID-19 was a “little flu” and that the economic crisis created by a strict quarantine would harm the population more than the outbreak itself. He has pushed for schools, universities, and businesses to return to normal activities. In contrast, the former health minister supported social distancing and other restrictive measures, openly criticizing the president for not supporting them.

Disinformation architecture

The main piece of disinformation that emerged against Mandetta attempted to connect him to the leftist Worker’s Party, known as PT in Portuguese, as well as to corruption schemes. The campaign first appeared on April 4, one day after a poll from Datafolha Institute suggested that only 33 percent of the Brazilian population supported Bolsonaro’s management of the outbreak, while 76 percent approved of health ministry actions. Bolsonaro is likely running for reelection in 2022.

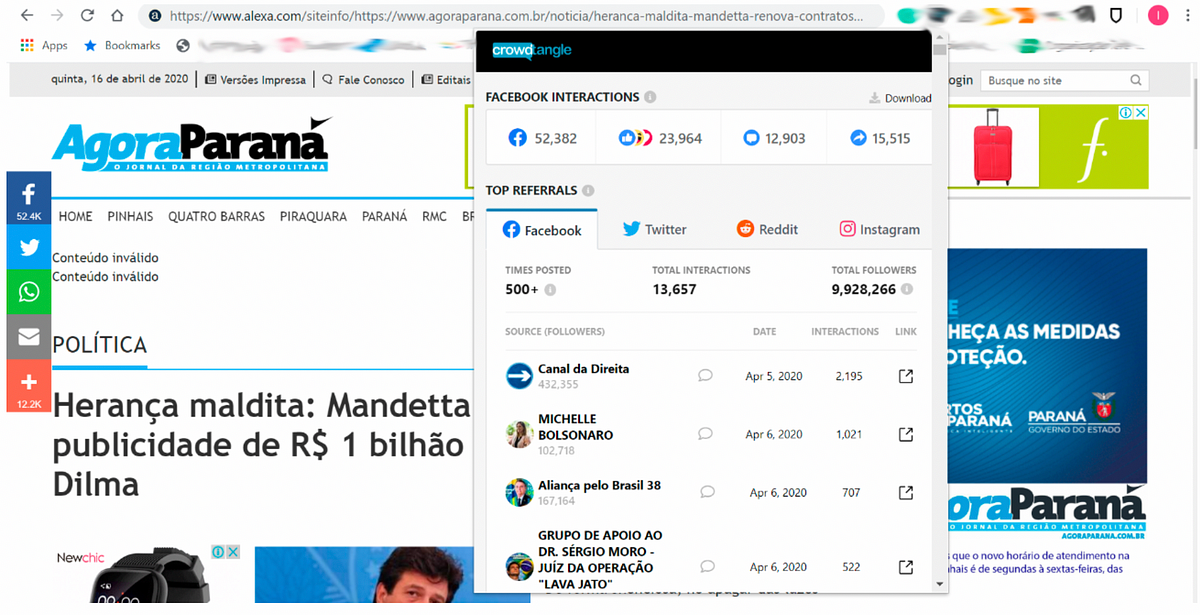

The pro-Bolsonaro website Agora Paraná published a misleading article claiming that Mandetta had renewed a contract — without the presidency’s knowledge — with publicity agencies that was first signed during a prior leftist government run by Dilma Rousseff of the PT. According to the site, these agencies bought ad space in Brazilian legacy media. In exchange, the story alleged, the media would protect Mandetta in their reporting while criticizing Bolsonaro. The story was false, as the contract in question was actually signed under the right-leaning administration of Michel Temer. Its December 2019 renewal, publicly documented in Brazil’s federal gazette, took place to avoid the contract from expiring at the end of that year.

Despite its inaccuracies, the article received more than 60,000 engagements on social media. On Facebook, it was published in pages and groups that support the president.

The article was also reproduced by other pro-Bolsonaro websites, garnering more than 80,000 interactions. Meanwhile, articles attempting to debunk the report received some 7,600 engagements.

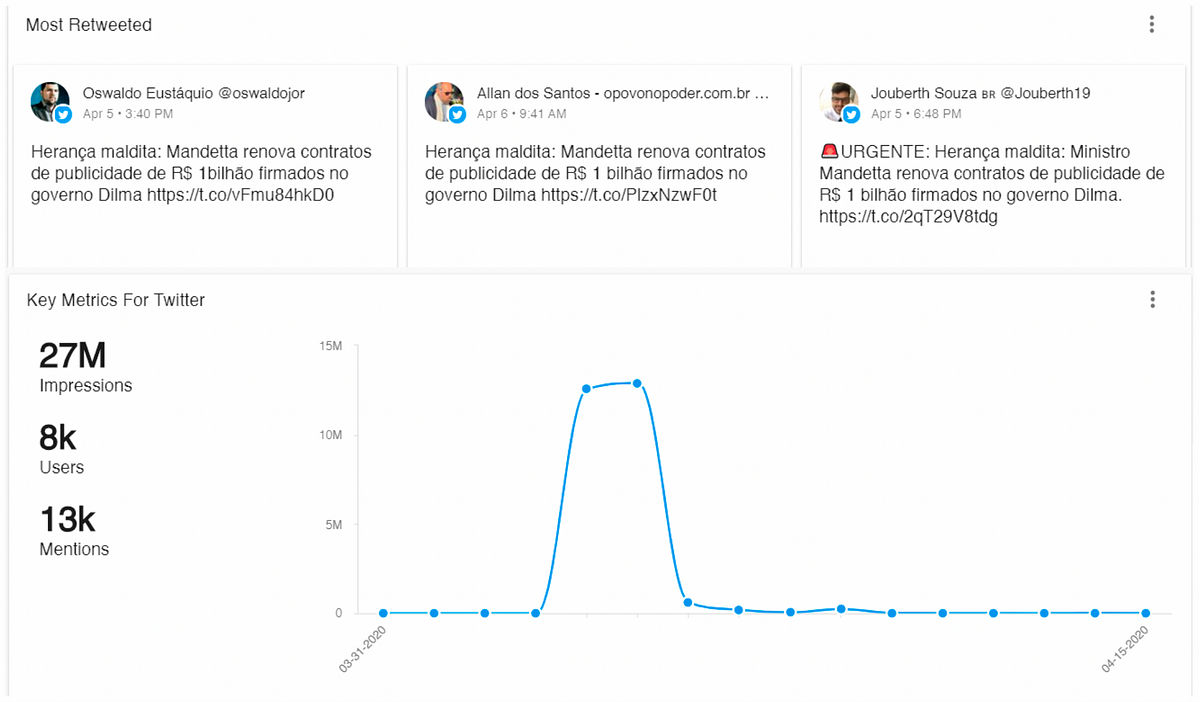

These claims were marked as false by Facebook, and pro-Bolsonaro influencers moved the claim to Twitter, where they were the main amplifiers of this piece of disinformation. The most retweeted post was from the owner of Agora Paraná, Oswaldo Eustáquio, followed by Allan dos Santos, who owns another pro-Bolsonaro website, and pro-Bolsonaro social media influencer Jouberth Souza. The false information was mentioned at least 12,600 times on Twitter, according to a search done with the social listening tool Meltwater Explore.

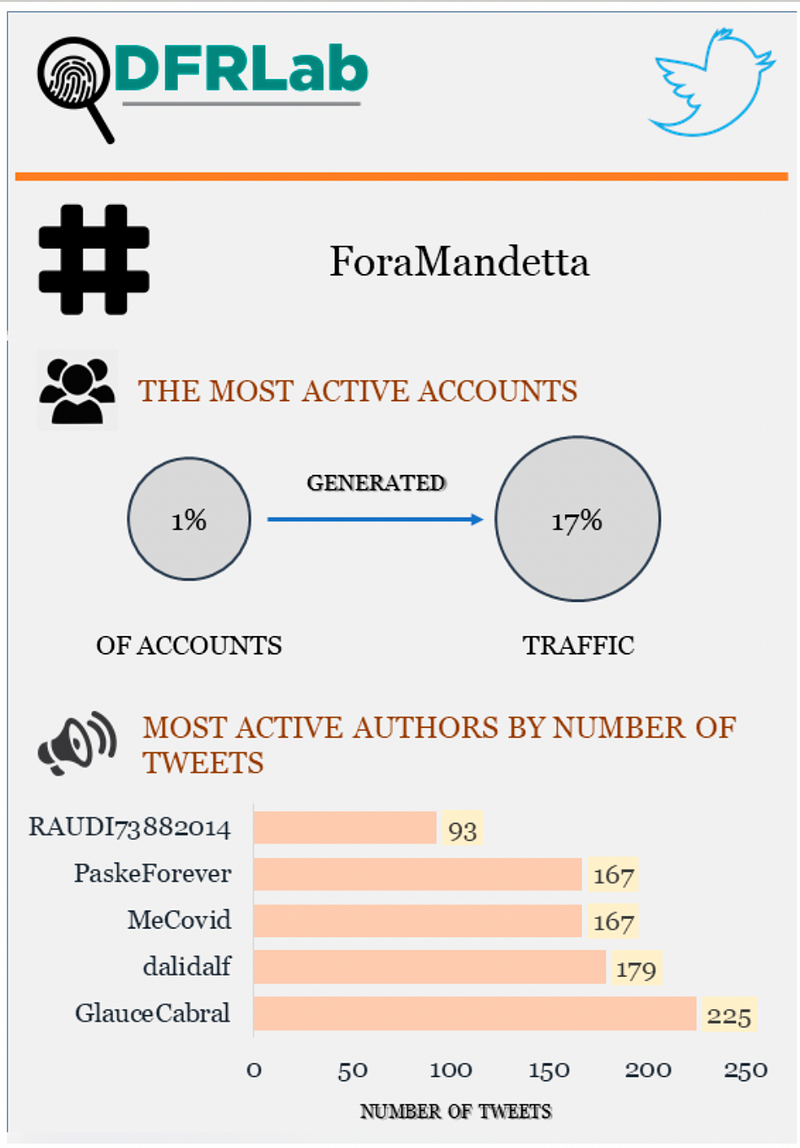

Bolsonaro supporters also pushed the hashtag #ForaMandetta (“Out, Mandetta”) to trend on the platform on April 3. An analysis of the hashtag’s history showed that the 1 percent most-active accounts using the hashtag were responsible for 17 percent of its total traffic. The most active account tweeted the hashtag 225 times in one day. This suggests that a small group of accounts was using the hashtag repeatedly to place it in the trending topics.

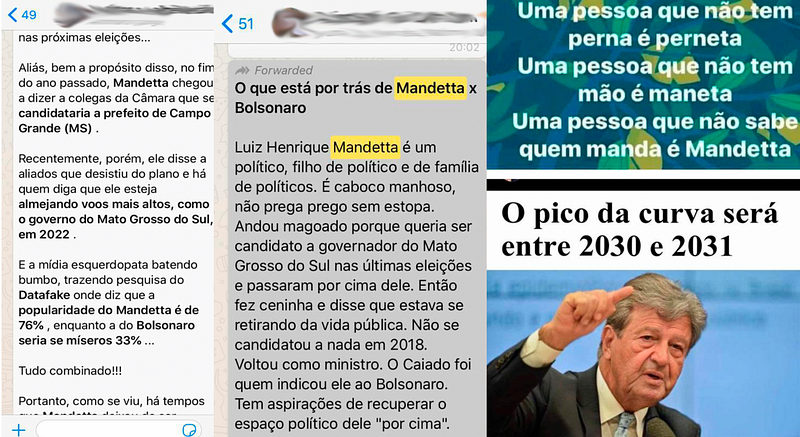

The article linking Mandetta to PT, as well as other anti-Mandetta messages, soon started to circulate on WhatsApp. The app is one of the most popular in Brazil, with around 120 million users. Political messages on WhatsApp are particularly popular among Bolsonaro supporters: groups supporting the president helped pioneer the use of the platform for political discussions dating back to the 2018 election campaign cycle.

Since WhatsApp is a closed messaging app, it is difficult to estimate the reach or identify the origin of messages that circulate within it. Yet it is clear that the narratives in these messages aimed at discrediting Mandetta, just like the ones that circulated in pro-Bolsonaro media. These “WhatsApp chains,” similar to email chains, claimed that Mandetta’s pro-quarantine actions were motivated by politics, rather than health concerns.

The defamatory campaign against Luiz Henrique Mandetta illustrates a new trend in Brazil’s information environment. Since Jair Bolsonaro was elected president of Brazil, public figures and decision-makers that disagree with him have often found themselves targeted by a disinformation machine that acts to discredit these actors on different platforms.

In the case of Mandetta, the defamatory campaign amplified to discredit him did not appear to resonate among all Brazilians, as people in multiple cities engaged in pot-banging protests in opposition to his ouster as minister of health. Yet the campaign does appear to have been effective among Bolsonaro supporters who, like Bolsonaro himself, continue to amplify narratives that minimize the severity of the disease and discredit social distancing measures.

Luiza Bandeira is a Research Associate, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along on Twitter for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.